Subh-i-Azal

Ṣubḥ-i-Azal (Persian: یحیی صبح ازل)(Morning of Eternity)[1] (1831–1912, born Mírzá Yaḥyá Núrí) was a Persian religious leader of Azali Bábism[1] also known as the Bayání Faith.

Subh-i-Azal | |

|---|---|

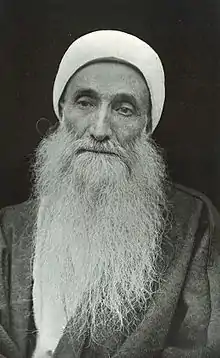

Ṣubḥ-i Azal at the age of 80, unknown photographer, Famagusta, 1911 circa, published in Harry Charles Lukach, The Fringe of the East, London, MacMillan, 1913, p.264. | |

| Born | Mírzá Yahya Núrí 1831 |

| Died | April 29, 1912 (aged 81) (In the lunar calendar he would have been about 82-3.) Famagusta , Ottoman Empire (present-day Cyprus) |

| Known for | Founder of Azali Babism |

| Successor | Disputed |

Born in the year 1831, he was orphaned at a very young age and taken into the care of his stepmother, Khadíjih Khánum. In 1850, when he was just 19 years old, he was appointed by 'Ali Muhammad Shirazi, known as the Báb, to lead the Bábí community.

Titles

His most widely known title, "Subh-i-Azal" appears in an Islamic tradition called the Hadith-i-Kumayl (Kumayl was a student of the first Imam, Ali) which the Báb quotes in his book Dalá'il-i-Sab'ih.

It was common practice among the Bábís to receive titles. The Báb's Will and Testament addresses Mirza Yahya in the first verse:

- "Name of Azal, testify that there is no God but I, the dearest beloved."[3]

Manuchehri (2004) notes that Mirza Yahya was the only Bábí with such a title as "Azal".[3]

However, the Báb appears to mention him only occasionally, if ever, specifically as "Subh-i-Azal", while attributing others with the title. He appeared to prefer calling him "Thamaratu'l-Azaliyya" and "'Ismu'l-Azal", while in early books he is called "Hadrat-i-Azal". This has led certain academics to doubt its origin, although they cite error, rather than deception as a motive.[4] There are also references to the titles al-Waḥīd, Ṭalʻat an-Nūr, and at-Tamara.[1]

Life

| Part of a series on |

| Bábism |

|---|

|

| Founder |

| Prominent people |

| Key scripture |

| History |

| Divisions |

| Other topics |

|

Early life

Subh-i-Azal was born in 1831 to Kuchak Khanum-i-Karmanshahi and Mírzá Buzurg-i-Núrí, in the province of Mazandaran, and a younger-half-brother of Baháʼu'lláh. His father was a minister in the court of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. His mother died while giving birth to him, and his father died in 1834 when he was three years old. His father is buried at Vadi-al-Islam in Najaf. He was committed to the care of his stepmother Khadíjih Khánum, the mother of Baháʼu'lláh.[5]

Becoming a Bábí

In 1845, at about the age of 14, Subh-i-Azal became a follower of the Báb.[5]

Early activities in the Bábí community

Subh-i-Azal met Tahirih, the 17th Letter of the Living who had, upon leaving the Conference of Badasht, traveled to Nur to propagate the faith. Shortly thereafter, she arrived at Barfurush and met Subh-i-Azal and became acquainted once again with Quddús who instructed her to take Subh-i-Azal with her to Nur. Subh-i-Azal remained in Nur for three days, during which he propagated the new faith. [6]

During the Battle of Fort Tabarsi, Subh-i-Azal, along with Baháʼu'lláh and Mirza Zayn al-Abedin endeavoured to travel there to assist the soldiers. However, they were arrested several kilometers from Amul. Their imprisonment was ordered by the governor, but Subh-i-Azal escaped the officials for a short while, after which he was discovered by a villager and then brought to Amul on foot with his hands tied. On the path to Amul he was subject to harassment, and people are reported to have spat at him. Upon arriving he was reunited with the other prisoners. The prisoners were ordered to be beaten, but when it came time that Subh-i-Azal should suffer the punishment, Baha'u'llah objected and offered to take the beating in his place. After some time, the governor wrote to Abbas Quli Khan who was commander of the government forces stationed near Fort Tabarsi. Khan replied back to the governor's correspondence, saying that the prisoners were of distinguished families and should not be harassed. Thus, the prisoners were released and sent to Nur upon orders of the commander.

Appointment as the Báb's successor

According to Baháʼí sources, shortly before the Báb's execution, one of the Báb's scribes, Mullā ʻAbdu'l-Karīm Qazvīnī, brought to the Báb's attention the necessity to appoint a successor; thus the Báb wrote a certain number of tablets which he gave to Mullā ʻAbdu'l-Karīm to deliver to Subh-i-Azal and Baháʼu'lláh.[7] These tablets were later interpreted by both Azalis and Baháʼís as proof of the Báb's delegation of leadership.[7] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá states that the Báb did this at the suggestion of Baháʼu'lláh.[8][9][10]

In his history, Nuqtat'ul-Kāf, Hājjī Mirzā Jāni Kāshānī (d. 1852) instead states the following:

...After the martyrdom of Hazrat-i-Kuddús and his companions, the Master was filled with sadness, until such time as the writings of Jenáb-i-Ezel met his gaze, when, through the violence of his delight, he rose up and sat down several times, pouring forth his gratitude to the God whom he worshipped...About forty days after his departure the news of the martyrdom of Hazrat-i-Kuddús came to Jenáb-i-Ezel. I have heard that after receiving this news he suffered for three days from a violent fever, induced by the burning heat of the fire of separation; and that after the three days the signs of holiness (áthár-i-kudsí) appeared in his blessed form and the mystery of the 'Return' was [once more] manifest. This event took place in the fifth year of the Manifestation of the Truth, so that Jenáb-i-Ezel became the blessed Earth of Devotion, and His Holiness 'the Reminder' [i.e. the Báb] appeared as the Heaven of Volition...Now when the letters of Jenáb-i-Ezel came to His Holiness 'the Reminder' [i.e. the Báb] he rejoiced exceedingly, and thenceforth began the decline of the Sun of 'the Reminder' and the rising of the Moon of Ezel. So he [i.e. the Báb] sent his personal effects, such as pen-cases, paper, writings, his own blessed raiment [i.e. his clothing], and his holy rings, according to the Number of the Unity [Váhid = 19], that the outward form might correspond with the inward reality. He also wrote a testamentary deposition, explicitly nominating him [i.e. Ezel] as his successor [Walí], and added, 'Write the eight [unwritten] Váḥids of the Beyán, and, if " He whom God shall manifest" should appear in His power in thy time, abrogate the Beyán; and put into practice that which we shall inspire into thine heart.' Now the mystery of his bestowing his effects on Ezel according to the 'Number of the Unity' is perfectly evident, namely that he intended the inner meaning thereof, that it might be known to all his followers that after himself Ezel should bear the Divine influences. And his object in explicitly nominating him as his successor also was to re-assure the hearts of the weak, so that they might not be bewildered as to his real nature, but that enemies and friends alike might know that there is no intermission in God's grace, and that God's religion is a thing which must be made manifest. And the reason why [the Báb] himself refrained from writing the eight [unwritten] Váḥids of the Beyán, but left them to Ezel, was that all men might know that the Tongue of God is one, and that He in Himself is a sovereign Proof. And what he meant by 'Him whom God should manifest' after himself was Hazrat-i-Ezel and none other than him, for there may not be two ' Points ' at one time. And the secret of the Báb's saying, 'Do thus and thus', while Ezel was himself also a 'Proof', was that at this time His Holiness 'the Reminder was the Heaven of Volition, and Ezel was accounted the Earth of Devotion and the product of purified gifts, wherefore was he thus addressed. In short, as soon as the time had come when the 'Eternal Fruit' [Thamara-i-Ezeliyyé] had reached maturity, the Red Blossom of Reminder-hood [i.e. the Báb], casting itself from the branch of the Blessed Tree of the Ká'imate (which is 'neither of the East nor of the West') to the simoom-wind of the malice of foes, destroyed itself, and prepared to ascend from the outward and visible 'World of Dominion' to the inward realm of the Mystery of Godhead...[11]

The French diplomat and scholar A.-L.-M. Nicolas maintains that Subh-i-Azal's claim to successorship is obvious;.[12] The Baháʼís hold that the Báb, for the purposes of secrecy, when corresponding with Baháʼu'lláh would address the letters to Subh-i-Azal.[13] After the Báb's death Subh-i-Azal came to be regarded as the central authority in the movement to whom the majority of Bábís turned as a source of guidance and revelation.[14]

During the time that both Baháʼu'lláh and Subh-i-Azal were in Baghdad, Baháʼu'lláh publicly and in his letters pointed to Subh-i-Azal as the leader of the community.[13] However, since Subh-i-Azal remained in hiding, Baháʼu'lláh performed much of the daily administration of the Bábí affairs.[13] Then, in 1863 Baháʼu'lláh made a claim to be Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest, the messianic figure in the Báb's writings, to a small number of followers, and in 1866 he made the claim public.[1] Baháʼu'lláh's claims threatened Subh-i-Azal's position as leader of the religion since it would mean little to be leader of the Bábís if "Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest" were to appear and start a new religion.[13] Subh-i-Azal responded to these claims with severe criticism, but his attempt to preserve the traditional Bábísm was largely unpopular, and his followers became the minority.[1]

Subh-i-Azal's leadership was controversial. He generally absented himself from the Bábí community spending his time in Baghdad in hiding and disguise.[1][13][15] Subh-i-Azal gradually alienated himself from a large proportion of the Bábís who started to give their alliance to other claimants.[1] Manuchehri states that Subh-i-Azal remained in hiding because he was primarily concerned with personal safety, due to a statement from the Báb in his will and testament that Subh-i-Azal should protect himself.[3]

MacEoin further states:

Baháʼí polemic has made much capital out of Azal's behaviour at this period, attributing it to a mixture of incompetence and cowardice. But it is clear that he actually continued to identify himself as the head of the Bábís, to write books, reply to letters, and on occasion meet with other leaders of the community His behaviour seems, therefore, to have been dictated less by cowardice than by the adoption of a policy of taqiyya [dissimulation]. Not only was this an approved practice in Shiʻism, but there was particular sanction for it in the seclusionist policies of the last Imams and, in particular, the original ghayba [Occultation] of the Twelfth Imam, who went into hiding out of fear of his enemies.[16]

Baghdad

In 1852, Subh-i-Azal was involved in an uprising in Takur, Iran, which was planned to coincide with the assassination attempt on the life of the Shah.[17] Following the attempt, he and other Babis chose to go into exile in Baghdad.[1] In Baghdad he lived as the generally acknowledged head of the community, but he kept his whereabouts secret from most of the community, instead keeping in contact with the Babis through agents, termed "witnesses", in Iran and Iraq to routinize the charismatic authority of the movement,[1] and echoing "the supposed appointment of agents by the twelfth Imam during the lesser occultation." One of the most important "witnesses of the Bayán" who represented Subh-i-Azal in Baghdad was Sayyid Muhammad Isfahani. Apart from Isfahani, Subh-i-Azal had written to six other individuals naming them all "witnesses of the Bayán." These witnesses are as follows: Mulla Muhammad Ja'far Naraqi, Mulla Muhammad Taqi, Haji Sayyid Muhammad (Isfahani), Haji Sayyid Jawad (al-Karbala'i), Mirza Muhammad Husayn Mutawalli-bashi Qummi, and Mulla Rajab 'Ali Qahir.[18]

Challenges to Baháʼu'lláh's authority

In 1863 Bahá’u’lláh made a claim to be Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest, the messianic figure in the Báb's writings, to a small number of followers, and in 1866 he made the claim public. Bahá’u’lláh's claims threatened Subh-i-Azal's position as leader of the religion since it would mean little to be leader of the Bábís if "Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest" were to appear and start a new religion. Subhh-i-Azal responded by making his own claims, but his attempt to preserve the traditional Bábísm was largely unpopular, and his followers became the minority.

Dayyán

The most serious challenge to the authority of Subh-i-Azal came from Mirza Asad Allah Khu'i "Dayyán," whose activities incited him to write a lengthy refutation titled "Mustayqiz." The Hasht Bihisht refers to Dayyán as "the Judas Iscariot of his people." Following the Báb's death, Dayyán, who had a deep interest in the study of the occult in regards to such areas as alchemy and gematria, began to advance his own claims to be Him Whom God shall make manifest. MacEoin reports that Mirza Muhammad Mazandarani, a follower of Subh-i-Azal murdered Dayyan for his claims in response to an order by Subh-i-Azal for him to be killed.[19]

Exile

In 1863 most of the Babis were exiled by the Ottoman authorities to Adrianople.[17] In Adrianople, Baháʼu'lláh made his claim to be the messianic figure of the Bayan public, and created a permanent schism between the two brothers.[1][17] Subh-i-Azal responded to these claims by making his own claims and resisting the changes of doctrine which were introduced by Baháʼu'lláh.[1] His attempts to keep the traditional Babism were, however, mostly unpopular.[1] During this time there was feuding between the two groups.

According to Balyuzi and some other sources, Subh-i-Azal was behind several murders and attempted murders of his enemies, including the poisoning of Baháʼu'lláh.[20][21][22] Some Azali sources re-apply these allegations to Baháʼu'lláh, even claiming that he poisoned himself while trying to poison Subh-i-Azal.[23] The second attempt in 1864 was more severe and had adverse effects on Bahaʼu'lláh throughout the remainder of His life until 1892, Mírzá Yahyá invites Baháʼu'lláh to a feast and shares a dish, half of which was laced with poison. Baháʼu'lláh is ill for 21 days following this attempt and is left with a shaking hand for the rest of His life

Finally the feuding between the two groups lead the Ottoman government to further exile the two groups in 1868; Baháʼu'lláh and the Baha'is were sent to Acre, Palestine and Subh-i Azal and his family, along with some followers were sent to Famagusta in Cyprus.[1]

Family

According to Browne, Mirza Yahya had several wives, and at least nine sons and five daughters. His sons included: Nurullah, Hadi, Ahmad, Abdul Ali, Rizwan Ali, and four others. Rizvan Ali reports that he had eleven or twelve wives.[24] Later research reports that he had up to seventeen wives including four in Iran and at least five in Baghdad, although it is not clear how many, if any, were simultaneous.[25] According to Azali sources, Subh-i-Azal had five wives in total.

Succession

There are conflicting reports as to whom Subh-i-Azal appointed as his successor. Browne reports that there was confusion over who was to be Subh-i-Azal's successor at his death. Subh-i-Azal's son, Rizwán ʻAli, reported that he had appointed the son of Aqa Mirza Muhammad Hadi Daulatabadi as his successor; while another, H.C. Lukach's, states that Mirza Yahya had said that whichever of his sons "resembled him the most" would be the successor. None appear to have stepped forward.[26] MacEoin reports that Subh-i-Azal appointed his son, Yahya Dawlatabadi, as his successor, but notes that there is little evidence that Yahya Dawlatabadi was involved in the affairs of the religion,[1] and that instead he spent his time as that of secular reformer.[17] Shoghi Effendi reports that Mirza Yahya appointed a distinguished Bábí, Aqa Mirza Muhammad Hadi of Daulatabad (Mirza Hadiy-i-Dawlat-Abadi) successor, but he later publicly recanted his faith in the Báb and in Mirza Yahya. Mirza Yahya's eldest son apparently became a Baháʼí himself.[27][28] Miller quoting a later source states that Yahya did not name a successor.[29] Miller relied heavily on Jalal Azal who disputed the appointment of Muhammad Hadi Daulatabadi.[30]

MacEoin notes that after the deaths of those Azali Babis who were active in the Constitutional Revolution in Iran, the Azali form of Babism entered a stagnation which it has not recovered as there is no acknowledged leader or central organization.[1] Current estimates are that there are no more than a few thousand.[15][31]

Works

Large collections of Subh-i-Azal's works are found in the British Museum Library Oriental Collection, London; in the Browne Collection at Cambridge University; at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; and at Princeton University.[32] Some of his works are provided at [www.bayanic.com]. In the English introduction to "Personal Reminiscences of the Babi Insurrection at Zanjan in 1850," [33] E.G. Browne lists thirty-eight titles as being among the works of Subh-i-Azal. Browne lists them as follows:

- 1) Kitab-i Divan al-Azal bar Nahj-i Ruh-i Ayat

- 2) Kitab-i Nur

- 3) Kitab-i ʻAliyyin

- 4) Kitab-i Lamʻat al-Azal

- 5) Kitab-i Hayat

- 6) Kitab-i Jamʻ

- 7) Kitab-i Quds-i Azal

- 8) Kitab-i Avval va Thani

- 9) Kitab-i Mirʼat al-Bayan

- 10) Kitab-i Ihtizaz al-Quds

- 11) Kitab-i Tadliʻ al-Uns

- 12) Kitab-i Naghmat ar-Ruh

- 13) Kitab-i Bahhaj

- 14) Kitab-i Hayakil

- 15) Kitab fi Tadrib ʻadd huwa bi'smi ʻAli

- 16) Kitab-i Mustayqiz

- 17) Kitab-i Laʼali va Mujali

- 18) Kitab-i Athar-i Azaliyyih

- 19) Sahifih-ʼi Qadariyyah

- 20) Sahifih-ʼi Abhajiyyih

- 21) Sahifih-ʼi Ha'iyyih

- 22) Sahifih-ʼi Vaviyyih

- 23) Sahifih-ʼi Azaliyyih

- 24) Sahifih-ʼi Huʼiyyih

- 25) Sahifih-ʼi Anzaʻiyyih

- 26) Sahifih-ʼi Huviyyih

- 27) Sahifih-ʼi Marathi

- 28) Alvah-i Nazilih la tuʻadd va la tuhsa

- 29) Suʼalat va Javabat-i bi Hisab

- 30) Tafsir-i-Surih-i-Rum

- 31) Kitab-i Ziyarat

- 32) Sharh-i Qasidih

- 33) Kitab al-Akbar fi Tafsir adh-Dhikr

- 34) Baqiyyih-ʼi Ahkam-i Bayan

- 35) Divan-i Ashʻar-i ʻArabi va Farsi

- 36) Divan-i Ashʻar-i ʻArabi

- 37) Kitab-i Tuba (Farsi)

- 38) Kitab-i Bismi'llah

Notes

- MacEoin 1987.

- Manuchehri 2004

- Schaefer 2000, p. 631 quoted in The Universal House of Justice (28 May 2004). "Tablet of the Báb Lawh-i-Vasaya, "Will and Testament"; Titles of Mírzá Yahyá". Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- Atiyya Ruhi 2004.

- Kashani 1910, p. 241.

- Amanat 1989, p. 384

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1886, p. 37

- Taherzadeh 1976, p. 37

- Browne 1891, pp. 79–80

- Hamadani, Husayn. Tarikh-i-Jadid. (New History). Appendix II. Mirza Jani's History, pp. 374; 380-381

- Nicolas, A.L.M (1933). Qui est le succeseur du Bab?. Paris: Librairie d'Amerique et d'Orient. p. 15.

- Cole, Juan. "A Brief Biography of Baha'u'llah". Retrieved 2006-06-22.

- MacEoin, Denis. Studia Iranica: Divisions and Authority Claims in Babism, p. 99

- Barrett 2001, p. 246

- MacEoin, Denis. Studia Iranica: Divisions and Authority Claims in Babism, p. 108

- Campo 2009.

- MacEoin, Denis. Studia Iranica: Divisions and Authority Claims in Babism, p. 110

- MacEoin, Denis. Studia Iranica: Divisions and Authority Claims in Babism, p. 113

- Balyuzi 2000, pp. 225–226

- Browne 1918, p. 16

- Cole 2002

- Mirza Aqa Khan Kirmani made this claim later in his Hasht-Bihisht. This book is abstracted in part by Edward G. Browne in "Note W" of his translation of A Traveller's Narrative(ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1891).

- Browne 1897

- Momen 1991, pp. 87–96

- Browne 1918, pp. 312–314

- Effendi 1944, p. 233

- Momen 1991, p. 99

- Miller 1974, p. 107

- Momen 1991

- Azali. In Britannica 2011.

- Momen 2009.

- Browne 1897.

Sources

- Editors (28 September 2011). "Azali". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 2017-07-10.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Editors (28 November 2014). "Mirza Yahya Sobh-e Azal". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 2017-07-10.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1886). Browne, E.G. (Tr.) (ed.). A Traveller's Narrative: Written to illustrate the episode of the Bab. Los Angeles, USA: Kalimát Press (published 2004). ISBN 1-890688-37-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1868). Browne, E.G. (Tr.) (ed.). A Traveller's Narrative: Written to illustrate the episode of the Bab. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (published 1891). pp. (See Browne's "Introduction" and "Notes", esp. "Note W".).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Amanat, Abbas (1989). Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Babi Movement in Iran. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balyuzi, H.M. (2000). Baháʼu'lláh, King of Glory. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-328-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barrett, David (2001). The New Believers. London, UK: Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35592-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browne, E.G. (1918). Materials for the Study of the Bábí Religion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campo, Juan (2009). "Ṣubḥ-i Azal". Encyclopedia of Islam. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc.

- Campo, Juan (2009). "Babism". Encyclopedia of Islam. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc

"Most of the movement's [Babism's] survivors turned to the religion of Baha Ullah (the Bahai Faith) in 1863, but others stayed loyal to Ali Muhammad's designated heir, Mirza Yahya (or Subbh-i Azal, d. 1912), and this group of Babis became known as Azalis. Azali Babism survived a period of exile in Iraq and Turkey, and its adherents participated in the Iranian Constitutional Revoluion of 1906. A very small number of Babis survive today in the Central Asian republic of Uzbekistan." - Cole, Juan (2000). "Baha'u'llah's Surah of God: Text, Translation, Commentary". East Lansing, MI: H-Bahai.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frigerio, Fabrizio (2001). "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane : Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste". Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου (Proceedings of the III International Cyprological Congress). Nicosia, Cyprus. 3: 629–646.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamadani, Huseyn (1893). Browne, E.G. (Tr.) (ed.). The Tarikh-i-Jadid, or New History of Mirza 'Ali Muhammad The Bab. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. (See Browne's "Introduction" and "Appendix II" (pp. 327–396).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kashani, Jani (Attrib.) (1910). Browne, E.G. (ed.). Kitab-i Nuqtat al-Kaf: Being the Earliest History of the Babis. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacEoin, Denis (15 December 1987). "Azali Babism". Encyclopedia Iranica. III. pp. 179–181.

- MacEoin, Denis (1994). Rituals in Babism and Bahaism. London: British Academic Press.

- Manuchehri, Sepehr (1999). "The Practice of Taqiyyah (Dissimulation) in the Babi and Bahai Religions". Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 3 (3). Retrieved 2006-12-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manuchehri, Sepehr (2004). "The Primal Point's Will and Testament". Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 7 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, William M. (1974). The Baháʼí Faith: Its History and Teachings. William Carey Library. ISBN 0-87808-137-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (1991). "The Cyprus Exiles". Baháʼí Studies Bulletin: 81–113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (2009). "Yahyá, Mírzá (c. 1831-1912)". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nabíl-i-Zarandí (1932). Shoghi Effendi (tr.) (ed.). The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl's Narrative. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-900125-22-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicolas, A.-L.-M. (1933). Qui est le successeur du Bâb?. Paris: A. Maisonneuve. ISBN 978-2-7200-0395-0.

- Ruhi, Atiyya (7 August 2012). Fragment of Subh-i Azal's Biography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University, Qamartaj Dolatabadi Papers, Women's Worlds in Qajar Iran.

- Salmání, Muhammad-ʻAlíy (1982). My Memories of Baháʼu'lláh. Kalimát Press, Los Angeles, USA.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaefer, Udo; Towfigh, N; Gollmer, U (1995). Making the Crooked Straight: A Contribution to Baháʼí Apologetics. Oxford, UK: George Ronald (published 2002). ISBN 0-85398-443-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Peter (1988). The Baháʼí Religion, A Short Introduction to its History and Teachings. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-277-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1976). The Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh, Volume 1: Baghdad 1853-63. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-270-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1992). The Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-344-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Varnava; Coureas; Elia (2009). The Minorities of Cyprus: Development patterns and the identity of the internal-exclusion. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-4438-0052-5.

- Zanjání, ʻAbdu'l-Ahad (1897). E.G. Browne (tr.) (ed.). "Personal Reminiscences of the Babi Insurrection at Zanjan in 1850, written by Aqa ʻAbdu'l-Ahad-i-Zanjan". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 29: 761–827.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Subh-i-Azal |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subh-i-Azal. |

- Bayanic.com A website maintained by current followers of Subh-i-Azal