T. H. Marshall

Thomas Humphrey Marshall (1893–1981) was an English sociologist who is best known for his essay "Citizenship and Social Class".

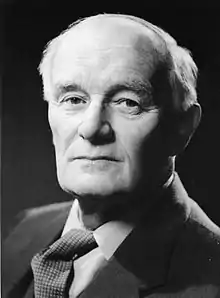

T. H. Marshall | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Marshall in c. 1950 | |

| Born | Thomas Humphrey Marshall 19 December 1893 London, England |

| Died | 29 November 1981 (aged 87) Cambridge, England |

| Political party | Labour |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Sociology |

| Sub-discipline | |

| School or tradition | |

| Institutions | |

| Notable works | "Citizenship and Social Class" (1950) |

| Notable ideas | Social citizenship |

| Influenced | David Lockwood[6] |

He was born on 19 December 1893 and was educated at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was a civilian prisoner in Germany during the First World War. He then went on to pursuing a fellowship program at Trinity College in October 1919, where he entered into academia as a professional historian. This was interrupted when he became the Labour candidate in Farnham in the 1922 election.[3] He later became a tutor in social work at the London School of Economics in 1925.[7] He was promoted to reader and went on to become the head of the Social Science Department at LSE from 1944 to 1949 and Martin White Professorship of Sociology from 1954 to 1956.[7] Then worked for UNESCO as the head of the Social Science Department from 1956 to 1960,[8] possibly contributing to the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which was drafted in 1954, but not ratified until 1966.

He was the fourth president of the International Sociological Association (1959–1962).[9]

Biography

T. H. Marshall was born in London on 19 December 1893 to a wealthy, artistically cultured family (a Bloomsbury family).[10] He was one of six children.[10] Because of his wealthy background, he attended Rugby School, a preparatory boarding school.[10] He continued his schooling at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied history.[3]

Marshall died on 29 November 1981 in Cambridge.

Philosophy of social science

Modern political science pioneer Seymour Martin Lipset argues that Marshall proposed a model of social science based on the middle-range theory of social structures and institutions, as opposed to grand theories of the purposes of development and modernisation, which were criticised by modern sociologists such as Robert K. Merton for being too speculative to provide valid results.[11] By using such a middle-range approach, Marshall and his mentor L. T. Hobhouse believed that rigid class distinctions could be dissolved and middle-class citizenship generalised through a careful understanding of social mechanisms. He also believed this would allow sociology to become an international discipline, helping "to increase mutual understanding between cultures" and further international co-operation.[12] While employing some concepts from Marxist conflict theory, such as social class and revolution, Marshall's analyses are based on functionalist concerns with phenomena such as "consensus, the normal, and anomie; co-operation and conflict; structure and growth," within self-contained systems.[13] Rather than studying "society", which may include non-systemic elements, Marshall argues that the task of sociology is:

the analytical and explanatory study of social systems....a set of interrelated and reciprocal activities having the following characteristics. The activities are repetitive and predictable to the degree necessary, first, to permit of purposeful, peaceful and orderly behaviour of the members of the society, and secondly to enable the pattern of action to continue in being, that is to say to preserve its identity even while gradually changing its shape.[14]

Whereas Marxists point to the internal contradictions of capital accumulation and class inequality (intra-systemic), Marshall sees phenomena that are anti-systemic as partly "alien" to the social system.[13]

Ideas

Citizenship

T. H. Marshall wrote a seminal essay on citizenship – which became his most famous work – titled "Citizenship and Social Class". This was published in 1950, based on a lecture given the previous year. He analysed the development of citizenship as a development of civil, then political, then social rights. With the civil rights being the first to be established, this included free speech, free religion, property ownership, and equal access to the legal system. Political rights followed by the right to vote and democracy. Lastly, social rights came with positive freedoms such as welfare rights.[15] Social rights happened because the arrival of the modern welfare state. These were broadly assigned to the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries respectively because of the "arrival of comprehensive civil rights" in the eighteenth century and the arrival of political rights in the nineteenth century.[16]

Social rights are awarded not on the basis of class or need, but rather on the status of citizenship. He claimed that the extension of social rights does not entail the destruction of social classes and inequality. T. H. Marshall was a close friend and admirer of Leonard Hobhouse, and his conception of citizenship emerged from a series of lectures given by Hobhouse at the LSE. Hobhouse is more philosophical, whereas Marshall is under the influence of measures taken by Lord Beveridge after the Second World War.[17] All of these people were involved in a turn in liberal thought that was called "new liberalism", a liberalism with a social conscience. T. H. Marshall also talks about industrial citizenship and its relationship with citizenship. He said that social rights are a precursor for political and civil rights.

Criticisms

Marshall's analysis of citizenship has been criticised on the basis that it only applies to males in England (note: England rather than Britain).[18] Marxist critics point out that Marshall's analysis is superficial as it does not discuss the right of the citizen to control economic production, which they argue is necessary for sustained shared prosperity. From a feminist perspective, the work of Marshall is highly constricted in being focused on men and ignoring the social rights of women and impediments to their realisation.[19] There is a debate among scholars about whether Marshall intended his historical analysis to be interpreted as a general theory of citizenship or whether the essay was just a commentary on developments within England.[20] The essay has been used by editors to promote more equality in society, including the "Black" vote in the US, and against Mrs. Thatcher in a 1992 edition prefaced by Tom Bottomore.[21] It is an Anglo-Saxon interpretation of the evolution of rights in a "peaceful reform" mode, unlike the revolutionary interpretations of Charles Tilly, the other great theoretician of citizenship in the twentieth century, who bases his readings in the developments of the French Revolution.

References

Footnotes

- Moses 2019b, p. 163.

- Marshall 1973, p. 406.

- Rocquin 2019, p. 87.

- Mason 2009, p. 95.

- Murray 2007, p. 223.

- Rose 1996, p. 386.

- Bulmer 2007, p. 91.

- Blyton 1982, pp. 157–158.

- "ISA Past Presidents". Madrid: International Sociological Association. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Marshall 1973, p. 399.

- Lipset 1965, pp. xvii–xviii.

- Marshall 1965a, pp. 47–48.

- Marshall 1965b, p. 33.

- Marshall 1965b, p. 28.

- Kivisto 2010.

- Moses 2019a, p. 128.

- Marshall 1973.

- Fraser, Nancy; Gordon, Linda (July–September 1992). "Contract Versus Charity: Why Is There No Social Citizenship in the United States?". Socialist Review. Vol. 23 no. 3.

- Turner 1993, pp. 3–4.

- Bulmer & Rees 1996, p. 270.

- Kivisto 2018.

Works cited

- Blyton, P. (1982). "T.H. Marshall, 1893–1981". International Social Science Journal. 91 (1).

- Bulmer, Martin (2007). "T. H. Marshall". In Scott, John (ed.). Fifty Key Sociologists: The Formative Theorists. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 91–94. doi:10.4324/9780203117279. ISBN 978-0-203-11727-9.

- Bulmer, Martin; Rees, Anthony M. (1996). "Conclusion: Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century". In Bulmer, Martin; Rees, Anthony M. (eds.). Citizenship Today: The Contemporary Relevance of T. H. Marshall. London: UCL Press.

- Kivisto, Peter, ed. (2010). Key Ideas in Sociology. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4833-4333-4.

- ——— (2018). "Citizenship: T.H. Marshall and Beyond". In Outhwaite, William; Turner, Stephen (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Political Sociology. London: SAGE Publications. pp. 413–428. doi:10.4135/9781526416513.n25. ISBN 978-1-5264-1651-3.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin (1965). Introduction. Class, Citizenship, and Social Development. By Marshall, T. H. (2nd ed.). Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

- Marshall, T. H. (1965a). "International Comprehension in Social Science". Class, Citizenship, and Social Development (2nd ed.). Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

- ——— (1965b). "Sociology – The Road Ahead". Class, Citizenship, and Social Development (2nd ed.). Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

- ——— (1973). "A British Sociological Career". The British Journal of Sociology. 24 (4): 399–408. doi:10.2307/589730. ISSN 0007-1315. JSTOR 589730.

- Mason, Ann C. (2009). "Citizenship Scarcity and State Weakness: Learning from the Colombian Experience". In Raue, Julia; Sutter, Patrick (eds.). Facets and Practices of State-Building. Leiden, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 75–103. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004174030.i-344.28. ISBN 978-90-474-2749-0.

- Moses, Julia (2019a). "The Reluctant Planner: T. H. Marshall and Political Thought in British Social Policy". In Goldman, Lawrence (ed.). Welfare and Social Policy in Britain Since 1870: Essays in Honour of Jose Harris. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 127ff. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198833048.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-883304-8.

- ——— (2019b). "Social Citizenship and Social Rights in an Age of Extremes: T. H. Marshall's Social Philosophy in the Longue Durée". Modern Intellectual History. 16 (1): 155–184. doi:10.1017/S1479244317000178.

- Murray, Georgina (2007). "Who Is Afraid of T. H. Marshall? Or, What Are the Limits of the Liberal Vision of Rights?". Societies Without Borders. 2 (2): 222–242. doi:10.1163/187219107X203577. hdl:10072/17742. ISSN 1872-1915. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Rocquin, Baudry (2019). British Sociologists and French "Sociologues" in the Interwar Years: The Battle for Society. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10913-4. ISBN 978-3-030-10912-7.

- Rose, David (1996). "For David Lockwood". The British Journal of Sociology. 47 (3): 385–396. doi:10.2307/591358. ISSN 1468-4446. JSTOR 591358.

- Turner, Bryan S., ed. (1993). Citizenship and Social Theory. SAGE Publications.

Further reading

- Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Catalogue of the Marshall papers held at LSE Archives

- Thomas Humphrey Marshall at the National Portrait Gallery, London

| Professional and academic associations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Georges Friedmann |

President of the International Sociological Association 1959–1962 |

Succeeded by René König |

| Preceded by Baroness Wootton of Abinger |

President of the British Sociological Association 1964–1969 |

Succeeded by Thomas Bottomore |