Tablet of Shamash

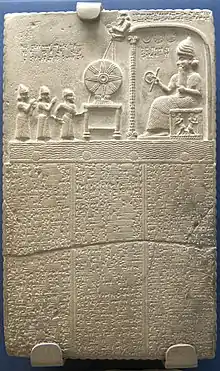

The Tablet of Shamash is a stone tablet recovered from the ancient Babylonian city of Sippar in southern Iraq in 1881; it is now a major piece in the British Museum's ancient Middle East collection. It is dated to the reign of King Nabu-apla-iddina ca. 888 – 855 BC.[1]

| Tablet of Shamash | |

|---|---|

Tablet of Shamash | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Size | Length: 29.2 cm, Width: 17.8 cm |

| Created | 888–855 BC |

| Present location | British Museum, London. Room 55. |

| Registration | ME 91000 |

Discovery

The tablet was discovered during excavations by Hormuzd Rassam between 1878 and 1883. The tablet was found complete but broken into two large and six small pieces. By the time of King Nabopolassar, between 625 and 605 BC, it had broken into four parts and been repaired. The terracotta coffer also contained two clay impressions of the tablets presentation scene. The coffer was sealed under an asphalt temple floor. It has been suggested that the coffer also contained a second tablet as well as a third clay impression (now in the Istanbul Museum).[3][4]

Description

It was encased in a clay cast or "squeeze" that created impressions when placed over the face of the stone and protected it. This indicates that the tablet was an item of reverence, possibly stored due to newer traditions. The tablet has serrated edges like a saw.[5] The bas-relief on the top of the obverse (pictured) shows Shamash, the Sun God, beneath symbols of the Sun, Moon and star. The God is depicted in a seated position, wearing a horned headdress, holding the rod-and-ring symbol in his right hand. There is another large sun disk in front of him on an altar, suspended from above by two figures. Of the three other figures on the left, the central one is dressed in the same fashion as Shamash and is assumed to be the Babylonian king Nabu-apla-iddina receiving the symbols of deity.

The bas relief can be superimposed with two orders of golden rectangles,[6] though ancient knowledge of the golden ratio before Pythagoras is considered unlikely.

Inscription

The scene contains three inscriptions.[7] The first, at the head of the tablet reads:

(1) ṣal-lam (ilu)Šamaš bêlu rabû |

(1) Image of Shamash, the great Lord |

Above the sun god a second inscription describes the position of the depicted moon, sun, and star as being over against the heavenly ocean, on which the scene sits:

(1) (ilu)Sin (ilu)Šamaš u (ilu)Ištar ina pu-ut apsî |

(1) Sin, Shamash and Ishtar are set over against the heavenly ocean |

The final inscription in the scene reads:

(1)agû (ilu)Šamaš |

(1) Headdress of Shamash |

The cuneiform text beneath the stele is divided into fifteen passages, blending prose, poetic and rhetorical elements in the fashion typical of Mesopotamian royal inscriptions. It tells how Sippar and the Ebabbar temple of Shamash had fallen into disrepair with the loss of the statue of the God. This cult image is temporarily replaced with the solar disk; it is further described how a new figure of Shamash was found in an eastern part of the Euphrates, from which Nabu-apla-iddina has constructed a new statue of lapis lazuli and gold to restore the cult. Similar iconographic and prosaic parallels have been evidenced from Mesopotamian and later Jewish sources where the king who restores the cult is seen like a deity passing on divine symbols. The remainder of the text records the gifts of the royal grant, similar to a kudurru and discusses the practices of the temple, priestly rules, dress codes and regulations.[8][9]

References

- British Museum. Dept. of Western Asiatic Antiquities; Richard David Barnett; Donald John Wiseman (1969). Fifty masterpieces of ancient Near Eastern art in the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities, the British Museum. British Museum. p. 41. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=369175&partId=1

- Hormuzd Rassam (1897), 401-402. Asshur and the Land of Nimrod: Being an Account of the Discoveries Made in the Ancient Ruins of Nineveh, Asshur, Sepharvaim, Calah, etc. Curts & Jennings.

- C. E. Woods, The Sun-God Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina Revisited, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 56, pp. 23 - 103, 2004

- Stefan Zawadzki (2006). Garments of the Gods: studies on the textile industry and the Pantheon of Sippar according to the texts from the Ebabbar archive. Saint-Paul. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-3-7278-1555-3. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Olsen, Scott (2006). The Golden Section: Nature's Greatest Secret. Glastonbury: Wooden Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-904263-47-0.

- British Museum Collection

- L. W. King (1912). Babylonian boundary-stones and memorial-tablets in the British Museum: with an atlas of plates. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Ḥevrah ha-ʻIvrit la-ḥaḳirat Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-ʻatiḳoteha (2003). Erets-Yiśraʼel: meḥḳarim bi-yediʻat ha-Arets ṿe-ʻatiḳoteha, pp. 91-110. ha-Ḥevrah ha-ʻIvrit la-ḥaḳirat Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-ʻatiḳoteha. ISBN 978-965-221-050-0. Retrieved 9 April 2011.