Benin Bronzes

The Benin Bronzes are a group of more than a thousand[lower-alpha 1] metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin in what is now modern-day Nigeria. Collectively, the objects form the best known examples of Benin art, created from the thirteenth century onwards, by the Edo people, which also included other sculptures in brass or bronze, including some famous portrait heads and smaller pieces.

| Benin Bronzes | |

|---|---|

A Benin Bronze plaque on display in the British Museum | |

| Material | mainly brass |

| Created | Edo people |

| Discovered | From 1897 on Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Benin (in present-day Nigeria) |

| Discovered by | British forces |

| Present location | Mainly in British Museum, others scattered around Europe and the US |

| Culture | Beninese, Edo |

.jpg.webp)

In 1897 most of the plaques and other objects were looted by British forces during a punitive expedition to the area as imperial control was being consolidated in Southern Nigeria.[3] Two hundred of the pieces were taken to the British Museum, London, while the rest were stolen by other European museums.[4] Today, a large number are held by the British Museum.[3] Other notable collections are in Germany and the USA.[5]

The Benin Bronzes led to a greater appreciation in Europe of African culture and art. Initially, it appeared incredible to the discoverers that people "supposedly so primitive and savage" were responsible for such highly developed objects.[6] Some even wrongly concluded that Benin knowledge of metallurgy came from the Portuguese traders who were in contact with Benin in the early modern period.[6] In actual fact the Benin Empire was a hub of African civilization before the Portuguese traders visited[7] and it is clear that the bronzes were made in Benin from an indigenous culture. Many of these dramatic sculptures date to the thirteenth century, centuries before contact with Portuguese traders, and a large part of the collection dates to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It is believed that two "golden ages" in Benin metal workmanship occurred during the reigns of Esigie (fl. 1550) and of Eresoyen (1735–50), when their workmanship achieved its highest qualities.[8]

While the collection is known as the Benin Bronzes, like most West African "bronzes" the pieces are mostly made of brass of variable composition.[lower-alpha 2] There are also pieces made of mixtures of bronze and brass, of wood, of ceramic, and of ivory, among other materials.[10]

The metal pieces were made using lost-wax casting and are considered among the best sculptures made using this technique.[11]

History

Social context and creation

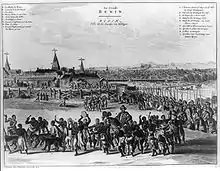

Olfert Dapper, a Dutch writer, describing Benin in his book Description of Africa (1668)[12]

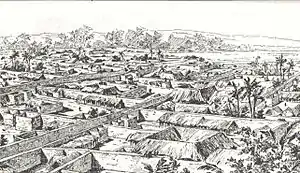

The Benin Empire, which occupied parts of present-day Nigeria between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries, was very rich in sculptures of diverse materials, such as iron, bronze, wood, ivory, and terra cotta. The Oba's palace in Benin, the site of production for the royal ancestral altars, also was the backdrop for an elaborate court ceremonial life in which the Oba, his warriors, chiefs and titleholders, priests, members of the palace societies and their constituent guilds, foreign merchants and mercenaries, and numerous retainers and attendants all took part. The palace, a vast sprawling agglomeration of buildings and courtyards, was the setting for hundreds of rectangular brass plaques whose relief images portray the persons and events that animated the court.[13]

Bronze and ivory objects had a variety of functions in the ritual and courtly life of the Kingdom of Benin. They were used principally to decorate the royal palace, which contained many bronze works.[14] They were hung on the pillars of the palace by nails punched directly through them.[13] As a courtly art, their principal objective was to glorify the Oba—the divine king—and the history of his imperial power or to honor the queen mother.[15] Art in the Kingdom of Benin took many forms, of which bronze and brass reliefs and the heads of kings and queen mothers are the best known. Bronze receptacles, bells, ornaments, jewelry, and ritual objects also possessed aesthetic qualities and originality, demonstrating the skills of their makers, although they are often eclipsed by figurative works in bronze and ivory carvings.[15]

In tropical Africa of the continent's center, the technique of lost-wax casting was developed early, as the works from Benin show. When a king died, his successor would order that a bronze head be made of his predecessor. Approximately 170 of these sculptures exist, and the oldest date from the twelfth century.[16] The Oba, or king, monopolized the materials that were most difficult to obtain, such as gold, elephant tusks, and bronze. These kings made possible the creation of the splendid Benin bronzes; thus, the royal courts contributed substantially to the development of sub-Saharan art.[17] In 1939, heads very similar to those of the Benin Empire were discovered in Ife, the holy city of the Yoruba, which dated to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This discovery supported an earlier tradition holding that it was artists from Ife who had taught Benin the techniques of bronze metalworking.[18] Recognition of the antiquity of the technology in Benin advanced when these sculptures were dated definitively to that era.[19]

European interest and the Benin Expedition of 1897

Few examples of African art had been collected by Europeans in the eighteenth century. Only at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when colonization and missionary activity began, did larger numbers of African works begin to be taken to Europe, where they were described as simple curiosities of "pagan" cults. This attitude changed after the Benin Expedition of 1897.

In 1897, the vice consul general James Robert Phillips, together with six other British officials, two businessmen, translators, and 215 porters, set off toward Benin from the small port of Sapele, Nigeria.[6] Although they had given word of their intended visit, they were later informed that their journey must be delayed, because no foreigner could enter the city while rituals were being conducted;[21][22] however, the travelers ignored the warning and continued on their expedition.[23] They were ambushed at the south of the city by Oba warriors, and only two Europeans survived the ensuing massacre.[6][21]

News of the incident reached London eight days later and a naval punitive expedition was organized immediately,[6][21][23] which was to be directed by Admiral Harry Rawson. The expedition sacked and totally destroyed Benin City.[6][21] Following the British attack, the conquerors took the works of art decorating the Royal Palace and the residences of the nobility, which had been accumulated over many centuries. According to the official account of this event written by the British, the attack by the British was warranted because the local people had ambushed a peaceful mission, and because the expedition liberated the population from a reign of terror.[21][24]

The works taken by the British were a treasure trove of bronze and ivory sculptures, including king heads, queen mother heads, leopard figurines, bells, and a great number of images sculpted in high relief, all of which were executed with a mastery of lost-wax casting. Later, in 1910, the German researcher Leo Frobenius carried out an expedition to Africa with the aim of collecting works of African art for museums in his country.[25] Today perhaps as few as fifty pieces remain in Nigeria although approximately 2,400 pieces are held in European and American collections.[26]

Division among museums

.jpg.webp)

The Benin Bronzes that were part of the booty of the punitive expedition of 1897 had different destinations: one portion ended up in the private collections of various British officials; the Foreign and Commonwealth Office sold a large number, which later ended up in various European museums, mainly in Germany, and in American museums.[5] The high quality of the pieces was quickly reflected in the high prices they fetched on the market. The Foreign Office gave a large quantity of bronze wall plaques to the British Museum; these plaques illustrated the history of the Benin Kingdom in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.[24]

In 1984, Sotheby's auctioned a plaque depicting a musician. The value was estimated at between £25,000 and £35,000 in the auction catalog.[24]

| Museum collections of Benin Bronzes[27] | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | Museum | Number of pieces |

| London | British Museum | 700 |

| Berlin | Ethnological Museum of Berlin | 580 |

| Oxford | Pitt Rivers Museum | 327 |

| Vienna | Weltmuseum Wien | 200 |

| Hamburg | Museum of Ethnology, Museum of Arts and Crafts | 196 |

| Dresden | Dresden Museum of Ethnology | 182 |

| New York | Metropolitan Museum of Art | 163 |

| Philadelphia | University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology | 100 |

| Leiden | National Museum of Ethnology | 98 |

| Leipzig | Museum of Ethnography | 87 |

| Cologne | Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum | 73 |

| Boston | Museum of Fine Arts | 28[28] |

| Zürich | Rietberg Museum | 2 |

| Dallas | Dallas Museum of Art | Probably 1 |

| San Francisco | De Young Museum | Probably 1 |

Subsequent sales

The two largest collections of Benin Bronzes are located in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin and in the British Museum in London, while the third largest collection is located in several museums in Nigeria (principally the Nigerian National Museum in Lagos).[29]

Since gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria has sought the return of these artifacts on several occasions.[29] The debate over the location of the bronzes in relation to their place of origin has been in contention. Often, their return has been considered an icon of the repatriation of the African continent. The artifacts have become an important example in the international debate over restitution, comparable to that of the Elgin Marbles.[30][31]

The British Museum sold more than 30 Benin Bronzes to the Nigerian government between 1950 and 1972. In 1950, the museum's curator Hermann Braunholtz declared that, although made individually, of the 203 plaques acquired by the Museum in 1898, 30 were duplicates; because they were identical representations, he determined that they were superfluous for the museum and were sold.[31] The sales stopped in 1972 and the museum's African art specialist said that they regretted the sales.[31]

The works

The Benin Bronzes are more naturalistic than most African art of the period. The bronze surfaces are designed to highlight contrasts between light and metal.[32] The features of many of the heads are exaggerated from natural proportions, with large ears, noses, and lips, which are shaped with great care.[33] The most notable aspect of the works is the high level of the great metal working skill at lost-wax casting. The descendants of these artisans still revere Igue-Igha, as the person who introduced the art of casting to the Kingdom of Benin.[32]

Another important aspect of the works is their exclusivity: property was reserved only for certain social classes, reflecting the strict hierarchical structure of society in the Kingdom of Benin. In general, only the king could own objects made of bronze and ivory, however, he could allow high-ranking individuals to use such items, such as hanging masks and cuffs made of bronze and ivory. Coral was also a royal material. Coral neck rings were a symbol of nobility and use was granted specifically by the Oba.[15]

Themes

The rectangular plaques exist in two formats. In one, the long vertical sides are turned back, creating a small edge that is decorated with an incised guilloche pattern. In the other format, which is much narrower, the turned-back edges are missing and the design of the plaque background ends abruptly, as if cut off. These variations probably reflect the size and shape of the palace pillars and the arrangement of the plaques on them. The plaques are generally about 1/8 inch thick.[13]

The backgrounds on the front of most of the plaques are incised with foliate patterns bearing one to four leaves, which is referred to as ebe-ame, or the "river leaf" design.[34] The leaves were used in healing rites by priestesses of Olokun, the god of the sea.[35]

Some of the reliefs represent important battles of the sixteenth-century wars of expansion, however, the majority depict noble dignitaries wearing splendid ceremonial dress. Most of the plaques portray static figures either alone, in pairs, or in small groups arranged hierarchically around a central figure. Many of the figures depicted in the plaques may be identified only according to their roles at court via their clothing and emblems, which indicated their function in the court, but not their particular historical identities. Although there have been attempts to link some of the depictions with historical figures, these identifications have been speculative and unverified. In certain cases, the lack of information even extends to the functional roles of some figures, which cannot conclusively be determined.[15]

The bronze heads were reserved for ancestral altars. They were also used as a base for engraved elephant tusks, which were placed in openings in the heads. The commemorative heads of the king or the queen mother were not individual portraits, although they show a stylized naturalism. Instead, they are archetypical depictions and the style of their design changed over the centuries, which also occurred with the insignias of the depicted royalty. The elephant tusks with decorative carvings, which may have begun being used as a decorative element in the eighteenth century, show distinct scenes from the reign of a deceased king.[15]

As a prerequisite for royal succession, each new Oba had to install an altar in honor of his predecessor. According to popular belief, a person's head was the receptacle of the supernatural guide for rational behavior. The head of an Oba was especially sacred, since the survival, security, and prosperity of all Edo citizens and their families, depended on his wisdom. In the annual festivals to reinforce the mystical power of the Oba, the king made ritual offerings in these sanctuaries, which were considered essential for the continuation of his reign. The stylistic variation of these bronze heads is such an important characteristic of Beninese art that it constitutes the principle scientific basis for establishing a chronology.[15]

The leopard is a motif that occurs throughout many of the Benin Bronzes, because it is the animal who symbolizes the Oba. Another recurring motif is the royal triad: the Oba in the centre, flanked by two assistants, highlighting the support of those in whom the king trusted in order to govern.[15]

According to some sources, the Benin artists may have been inspired by items brought during the arrival of the Portuguese, including European illuminated books, small ivory caskets with carved lids from India, and Indian miniature paintings. The quatrefoil "river leaves" might have originated from European or Islamic art,[13][34][36] but by contrast, Babatunde Lawal cites examples of relief carving in southern Nigerian art to support his theory that the plaques are indigenous to Benin.[37]

Technique

Although the works generally are called the Benin Bronzes, they are made of different materials. Some are made of brass, which metallurgical analysis has shown to be an alloy of copper, zinc, and lead in various proportions.[10] Others are non-metallic, made of wood, ceramics, ivory, leather, or cloth.[10]

The wooden objects are made in a complex process. It starts with a tree trunk or branch and is carved directly. The artist obtains the final form of the work from a block of wood. Since it was customary to use freshly cut wood in carvings, once the piece was finalized the surface was charred to prevent cracking during drying. This also allowed for polychromatic artworks, which were achieved using knife cuts and applications of natural pigments made with vegetable oil or palm oil. This type of grease, which was made near smoke from residences, allowed the wooden sculptures to acquire a patina that resembles rusty metal.[38]

The figures depicted in the bronzes were cast in relief with details incised in the wax model. Artists working in bronze were organized into a type of guild under royal decree and lived in a special area of the palace under the direct control of the Oba. The works made using lost-wax casting required great specialization. Their quality was superior when the king was especially powerful, allowing him to employ a great number of specialists.[39]

Although the oldest examples of similar Benin metal work in bronze date from the twelfth century, according to tradition, the lost-wax casting technique was introduced to Benin by the son of the Oni, or sovereign of Ife. Their tradition holds that he taught the Benin metal workers the art of casting bronze using lost-wax techniques during the thirteenth century.[40] These great Benin artisans refined that technique until they were able to cast plaques only an eighth-of-an-inch thick, surpassing the art as practiced by Renaissance masters in Europe.[32]

Reception

One of the bronzes was featured in A History of the World in 100 Objects, a series of radio programmes that started in 2010 as a collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum; it was also published as a book.[41] Credits: Mehar Sohail

References

Notes

- The exact number of pieces is uncertain.[1] Most sources speak of a thousand pieces or several thousand pieces. According to Nevadomsky, there were between 3,000 and 5,000 pieces in total.[2]

- The British Museum notes that the term "copper alloy" is more appropriate in museology as it avoids the distinction between brass and bronze.[9]

Footnotes

- Dohlvik 2006, p. 7.

- Nevadomsky 2005, p. 66.

- "British museums may loan Nigeria bronzes that were stolen from Nigeria by British imperialists". The Independent. 24 June 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Greenfield 2007, p. 124.

- Benin Diplomatic Handbook, p. 23.

- Meyerowitz, Eva L. R. (1943). "Ancient Bronzes in the Royal Palace at Benin". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd. 83 (487): 248–253. JSTOR 868735.

- "Benin and the Portuguese". Khan Academy. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Greenfield 2007, p. 122.

- British Museum, "Scope Note" for "copper alloy". Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved on 2014-05-26.

- Dohlvik 2006, p. 21.

- Nevadomsky 2004, pp. 1,4,86-8, 95-6.

- Willett 1985, p. 102.

- Ezra, Kate (1992). Royal art of Benin: the Perls collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6414-3.

- Pijoan 1966, p. 12.

- Plankensteiner, Barbara (December 22, 2007). "Benin--Kings and Rituals: court arts from Nigeria". African Arts. University of California. ISSN 0001-9933. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Gowing 1984, p. 578.

- Leuzinger 1976, p. 24.

- Huera 1988, p. 36.

- Huera 1988, p. 37.

- Willett 1985, pp. 100-1.

- Benin Diplomatic Handbook, p. 21.

- Dohlvik 2006, pp. 21-2.

- Greenfield 2007, p. 123.

- Darshana, Soni. "The British and the Benin Bronzes". ARM Information Sheet 4. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Huera 1988, p. 20.

- Huera 1988, p. 35.

- The collections listed are not exhaustive, and are intended to give the reader an idea of the dispersion of the artworks. For a more exhaustive list, consult: Dark, Philip J. C. (1973). An Introduction to Benin Art and Technology. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-0-19-817191-1.

- Robert Owen Lehman Collection, MFA Website, Accessed 7 August 2015

- Dohlvik 2006, p. 8.

- Dohlvik 2006, p. 24.

- "Benin bronzes sold to Nigeria". BBC News. March 27, 2002. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- "Sculpture: The Bronzes of Benin". TIME. August 6, 1965.

- Leuzinger 1976, p. 16.

- Dark, Philip (1973). An Introduction to Benin Art and Technology. Oxford.

- Ben Amos, Paula (1980). The Art of Benin. London.

- Fagg, William (1963). Nigerian Images. London.

- Lawal, Babatunde (1977). "The Present State of Art Historical Research in Nigeria: Problems and Possibilities". Journal of African History. 18 (2): 196–216. doi:10.1017/s0021853700015498.

- Beretta 1983, p. 356.

- Gowing 1984, p. 569.

- Huera 1988, p. 52.

- [A History of the World in 100 Objects]], BBC. accessed August 2010

Bibliography

- Lawrence Gowing, ed. (1984). Historia Universal del Arte (in Spanish). IV. Madrid: SARPE. ISBN 978-84-7291-592-3.

- Willett, Frank (1985). African Art: An Introduction (Reprint. ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20103-9.

- Beretta, Alcides; Rodenas, María Dolores (1983). Historia del Arte: La escultura del África negra (in Spanish). II. Barcelona: Carroggio. ISBN 978-84-7254-313-3.

- Dohlvik, Charlotta (May 2006). Museums and Their Voices: A Contemporary Study of the Benin Bronzes (PDF). International Museum Studies.

- Greenfield, Janette (2007). The Return of Cultural Treasures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80216-1.

- Hicks, Dan (2020). The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745341767.

- Huera, Carmen (1988). Historia Universal del Arte: África, América y Asia, Arte Primitivo. Barcelona: Planeta. ISBN 978-8432066900.

- Leuzinger, Elsy (1976). Arte del África negra (in Spanish). Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa. ISBN 978-84-343-0176-4.

- Lundén, Staffan (2016). Displaying Loot. The Benin objects and the British Museum. Gotark Series B, Göteborgs Universitet.

- Nevadomsky, Joseph (Spring 2004). "Art and Science in Benin Bronzes". African Arts. 37 (1): 1, 4, 86–88, 95–96. doi:10.1162/afar.2004.37.1.1. JSTOR 3338001.

- Nevadomsky, Joseph (2005). "Casting in Contemporary Benin Art". African Arts. 38 (2): 66–96. doi:10.1162/afar.2005.38.2.66.

- Pijoan (1966). Pijoan-Historia del Arte. I. Barcelona: Salvat Editores.

- Benin Diplomatic Handbook. International Business Publications. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7397-5745-1.

| Preceded by 76: Mechanical Galleon |

A History of the World in 100 Objects Object 77 |

Succeeded by 78: Double-headed serpent |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benin bronzes. |