Temple Church

The Temple Church is a Royal peculiar[2] church in the City of London located between Fleet Street and the River Thames, built by the Knights Templar as their English headquarters. It was consecrated on 10 February 1185 by Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem.[3] During the reign of King John (1199–1216) it served as the royal treasury, supported by the role of the Knights Templar as proto-international bankers. It is now jointly owned by the Inner Temple and Middle Temple[4] Inns of Court, bases of the English legal profession. It is famous for being a round church, a common design feature for Knights Templar churches,[5] and for its 13th- and 14th-century stone effigies. It was heavily damaged by German bombing during World War II and has since been greatly restored and rebuilt.

| Temple Church | |

|---|---|

.jpeg.webp) Temple Church, view from south-west, showing the original Round Church, now forming the nave | |

| |

| Location | London, EC4 |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Catholic |

| Website | templechurch |

| History | |

| Consecrated | 10 February 1185 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Administration | |

| Deanery | City |

| Diocese | London |

| Clergy | |

| Priest(s) | Robin Griffith-Jones (Master of the Temple) Mark Hatcher (Reader of the Temple) |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Roger Sayer |

Temple Church, view from south-east showing the chancel and east end | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Temple Church (St Mary's) |

| Designated | 4 January 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1064646[1] |

The area around the Temple Church is known as the Temple.[6] Temple Bar, an ornamental processional gateway, formerly stood in the middle of Fleet Street. Nearby is the Temple Underground station.

History

Construction

In the mid-12th century, before the construction of the church, the Knights Templar in London had met at a site in High Holborn in a structure originally established by Hugues de Payens (the site had been historically the location of a Roman temple in Londinium, now known as London). Because of the rapid growth of the order, by the 1160s the site had become too confined, and the order purchased the current site for the establishment of a larger monastic complex as their headquarters in England. In addition to the church, the new compound originally contained residences, military training facilities, and recreational grounds for the military brethren and novices, who were not permitted to go into the City without the permission of the Master of the Temple.

_(14579114747).jpg.webp)

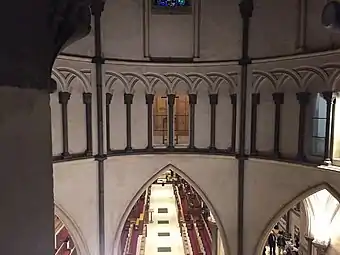

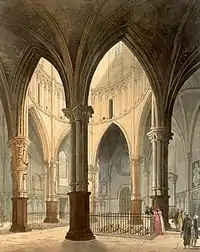

The church building comprises two separate sections: The original circular church building, called the Round Church and now acting as a nave, and a later rectangular section adjoining on the east side, built approximately half a century later, forming the chancel.

After the capture of Jerusalem in 1099 by the Crusaders, the Dome of the Rock was given to the Augustinians, who turned it into a church (while the Al-Aqsa Mosque became a royal palace). Because the Dome of the Rock was the site of the Temple of Solomon, the Knights Templar set up their headquarters in the Al-Aqsa Mosque adjacent to the Dome for much of the 12th century. The Templum Domini, as they called the Dome of the Rock, featured on the official seals of the Order's Grand Masters (such as Everard des Barres and Renaud de Vichiers), and along with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre upon which it was based soon became the architectural model for Round Templar churches across Europe.

The round church is 55 feet (17 m) in diameter, and contains within it a circle of the earliest known surviving free-standing Purbeck Marble columns. It is probable that the walls and grotesque heads were originally painted in colours.

It was consecrated on 10 February 1185[7] by Heraclius, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. It is believed that King Henry II (1154–1189) was present at the consecration.

1185–1307

The Knights Templar order was very powerful in England, with the Master of the Temple sitting in parliament as primus baro (the first baron in precedence of the realm). The compound was regularly used as a residence by kings and by legates of the Pope. The Temple also served as an early safety-deposit bank, sometimes in defiance of the Crown's attempts to seize the funds of nobles who had entrusted their wealth there. The quasi-supra-national independent network and great wealth of the Order throughout Europe, and the jealousy this caused in secular kingdoms, is considered by most commentators to have been the primary cause of its eventual downfall.

In January 1215 William Marshall (who is buried in the nave next to his sons, and is represented by one of the nine stone effigies)[8] served as a negotiator during a meeting in the Temple between King John and the barons, who demanded that the king should uphold the rights enshrined in the Coronation Charter of his predecessor and elder brother King Richard I. Marshall swore on behalf of the king that the grievances of the barons would be addressed in the summer, which led to the signing by the king of Magna Carta in June.

Marshall later became regent during the reign of John's infant son, King Henry III (1216–1272). Henry later expressed a desire to be buried in the church and, to accommodate this, in the early 13th century the chancel of the original church was pulled down and a new larger chancel was built, the basic form of which survives today. It was consecrated on Ascension Day 1240 and comprises a central aisle and two side aisles, north and south, of identical width. The height of the vault is 36 feet 3 inches (11.05 m). Although one of Henry's infant sons was buried in the chancel, Henry himself later altered his will to reflect his new wish to be buried in Westminster Abbey.

Crown seizure

After the destruction and abolition of the Knights Templar in 1307, King Edward II took control of the church as a Crown possession. It was later given to the Knights Hospitaller, who leased the Temple to two colleges of lawyers. One college moved into the part of the Temple previously used by the Knights, and the other into the part previously used by its clergy, and both shared the use of the church. The colleges evolved into the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple, two of the four London Inns of Court.

16th–19th centuries

In 1540 the church became the property of The Crown once again when King Henry VIII abolished the Knights Hospitaller in England and confiscated their property. Henry provided a priest for the church under the former title "Master of the Temple". In the 1580s the church was the scene of the Battle of the Pulpits, a theological conflict between the Puritans and supporters of the Elizabethan Compromise. Shakespeare was familiar with the site and the church and garden feature in his play Henry VI, part 1 as the setting for the fictional scene of the plucking of two roses of York and Lancaster and the start of the Wars of the Roses. In 2002 this event was commemorated with the planting of new white and red roses in the modern gardens.

Following an agreement in 1608 by King James I, the two Inns were granted use of the church in perpetuity on condition that they should support and maintain it. They continue to use the Temple church as their ceremonial chapel.

The church escaped damage in the Great Fire of London of 1666. Nevertheless, it was refurbished by Christopher Wren, who made extensive modifications to the interior, including the addition of an altar screen and the installation of the church's first organ. The church underwent a Victorian restoration in 1841 by Smirke and Burton, who decorated the walls and ceiling in high Victorian Gothic style in an attempt to return the church back to its supposed original appearance. Further restoration work was executed in 1862 by James Piers St Aubyn.

Twentieth century

On 10 May 1941, German incendiary bombs set the roof of the Round Church on fire,[9] and the fire quickly spread to the nave and chapel. The organ and all the wooden parts of the church, including the Victorian renovations, were destroyed and the Purbeck marble columns in the chancel cracked due to the intense heat. Although these columns still provided some support to the vault, they were deemed unsound and were replaced in identical form. The original columns had a slight outward lean, which architectural quirk was followed in the replacement columns.

During the renovation by the architect Walter Godfrey, it was discovered that elements of the 17th-century renovations made by Wren had survived in storage and these were replaced in their original positions. The church was rededicated in November 1958.[10]

The church was designated a Grade I listed building on 4 January 1950.[11]

Use

Among other purposes, the church was originally used for Templar initiation ceremonies. In England the ceremony involved new recruits entering the Temple via the western door at dawn. The initiates entered the circular nave and then took monastic vows of piety, chastity, poverty and obedience. The details of initiation ceremonies were always a closely guarded secret, which later contributed to the Order's downfall as gossip and rumours spread about possible blasphemous usages. These rumours were manipulated and exploited by the Order's enemies, such as King Philip IV of France, to fabricate a pretext for the order's suppression.

Today the Temple Church holds regular church services, including Holy Communion and Mattins on Sunday morning.[12] It also holds weddings, but only for members of the Inner and Middle Temples. The Temple Church serves both the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple as a private chapel.

The Temple Church has always been a Peculiar (but not a Royal Peculiar), due to which the choristers have the privilege of wearing scarlet cassocks. Debate exists regarding the relationship of its status as Crown Subject and Peculiar. Relations with the Bishop of London are very good and she regularly attends events and services at the Temple Church. The Bishop of London is also ex officio Dean of the Chapel Royal.

Music at the Temple Church

The church offers regular choral music performances and organ recitals. A choir in the English cathedral tradition was established at the Temple Church in 1842 under the direction of Dr E. J. Hopkins, and it soon earned a high reputation.[13]

In 1927, the Temple Choir under George Thalben-Ball became world-famous with its recording of Mendelssohn's Hear My Prayer, including the solo "O for the Wings of a Dove" sung by Ernest Lough. This became one of the most popular recordings of all time by a church choir, and it sold strongly throughout the twentieth century, reaching gold disc status (a million copies) in 1962 and achieving an estimated 6 million sales to date.

The Temple Church's excellent acoustics have also attracted secular musicians: Sir John Barbirolli recorded a famous performance of the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams there in 1962 (at the suggestion of Bernard Herrmann), and Paul Tortelier made his recording of the complete Bach Cello Suites there in April 1982.

In 2003 the church was the location of a music video of Libera.[14]

While writing the score for Interstellar, film composer Hans Zimmer chose the Temple Church for the recording of the parts of the score that included an organ. The Church's organist Roger Sayer played the organ, while a large orchestra played throughout the church.[15] Zimmer is quoted saying that "Setting foot into Temple Church is like stepping into profound history. ...Temple Church houses one of the most magnificent organs in the world."

The choir continues to record, broadcast and perform, in addition to its regular services at the Temple Church. It is an all-male choir, consisting of 18 boys who are all educated on generous scholarships (most of the boys attend the City of London School although the scholarship is portable) and 12 professional men. They perform weekly at Sunday services, 11:15–12:15 pm, during term time. The choir gave the world premiere of Sir John Tavener's epic The Veil of the Temple, which took place over seven hours during an overnight vigil in the Temple Church in 2003. The following year it was performed by the choir at the Lincoln Festival in New York City; a concert version was performed at the BBC Proms the same year. Two new recordings were released in 2010 on the Signum Classics label: one of the Temple Church Choir, and a recording of English organ music played by James Vivian. Both were critically acclaimed. The boys' choir also appears on the 2016 recording of John Rutter's violin concerto Visions, and on an album of upper-voices Christmas music released the same year.

Organ

The church contains two organs: a chamber organ built by Robin Jennings in 2001, and a four manual Harrison & Harrison organ, built in 1924 as a private ballroom organ at Glen Tanar Castle and installed at the Temple Church in 1954.[16][17]

List of organists

The church has had a number of famous organists, including:

- Francis Pigott 1688–1704

- John Pigott 1704–1737 (from 1729 for Middle Temple only)

|

Inner Temple

|

Middle Temple

|

(from 1814 for both Inner and Middle Temple)

- George Price 1814–1826

- George Warne 1826–1843 (afterwards organist of St Nicholas' Church, Great Yarmouth)

- Dr Edward John Hopkins 1843–1897

- Sir Henry Walford Davies 1897–1923

- Sir George Thalben-Ball 1923–1982

- Dr John Birch 1982–1997

- Stephen Layton 1997–2006

- James Vivian 2006–2013

- Roger Sayer 2014–[18]

Master of the Temple

The church always has two clergy, called the "Master of the Temple" and the "Reader of the Temple." The title of the Master of the Temple recalls the title of the head of the former order of the Knights Templar. The Master of the Temple is appointed by the Crown; the right of appointment was reserved when the Church was granted to the two Inns by James I in 1608. The church has the status of a peculiar rather than a private chapel and is outside any episcopal or archiepiscopal jurisdiction.[19] The present Master of the Temple is the Reverend Robin Griffith-Jones, appointed in 1999. The Master gives regular lunchtime talks open to the public.

The official title of the Master of the Temple is the "Reverend and Valiant Master of the Temple."[20] His official residence is the Master's House, a Georgian townhouse built next to the church in 1764.[21]

Masters of the Temple

- 1540–1558† William Ermested

- 1560–1584† Richard Alvey

- 1585–1591 Richard Hooker

- 1591–1601† Nicholas Balgay[22]

- 1601–1628† Thomas Master[23] (as Archdeacon of Salop from 1614)

- 1628–1639† Paul Micklethwaite[24]

- 1639–1644 John Littleton (royalist, left London to join the king, ejected 1644)[25]

(1644 Richard Vines nominated by the House of Commons[25] but rejected by the House of Lords.[26])

- 1645–1646 John Tombes[27]

- 1646–1658 Richard Johnson[27]

- 1658–1659† Ralph Brownrigg[28] (as Bishop of Exeter)

- 1659–1661 John Gauden[28] (as Bishop of Exeter)

- 1661–1684† Richard Ball[29]

- 1684–1704 William Sherlock (as Dean of St Paul's from 1691)

- 1704–1753 Thomas Sherlock[30] (as Dean of Chichester 1715, Bishop of Bangor 1728, Salisbury 1734, London 1748)

- 1753–1763† Samuel Nicolls[31]

- 1763–1771† Gregory Sharpe[32]

- 1771–1772† George Watts[33]

- 1772–1787 Thomas Thurlow[34] (as Dean of Rochester 1775, Bishop of Lincoln 1779)

- 1787–1797 William Pearce[35] (later Dean of Ely)

- 1797–1798 Thomas Kipling[36] (later Dean of Peterborough)

- 1798–1827 Thomas Rennell[37] (as Dean of Winchester from 1805)

- 1827–1845 Christopher Benson[38]

- 1845–1869 Thomas Robinson

- 1869–1894 Charles John Vaughan (as Dean of Llandaff from 1879)

- 1894–1904† Alfred Ainger

- 1904–1915† Henry George Woods

- 1915–1919 Ernest Barnes (later Bishop of Birmingham)

- 1919–1930 William Henry Draper

- 1930–1935 Spencer Carpenter (later Dean of Exeter)

- 1935–1954† Harold Anson

- 1954–1957† John Firth

- 1958–1968 Dick Milford

- 1968–1980 Bobby Milburn (formerly Dean of Worcester)

- 1981–1999† Joseph Robinson

- 1999– Robin Griffith-Jones

Buried in the church

- Sir Richard Chetwode, Sheriff of Northamptonshire (1560–1635).

- Silvester de Everdon, Bishop of Carlisle and Lord Chancellor of England (died 1254).[39]

- Sir Anthony Jackson (1599–1666).

- Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex (died September 1144).

- William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1146–1219).

- William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1190 – 6 April 1231).

- Gilbert Marshal, 4th Earl of Pembroke (1194 – 27 June 1241).

- Dr Richard Mead (1673–1754).

- William Petyt, barrister, legal scholar, and Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London (1640/1641 – 3 October 1707).

- Sir Edmund Plowden (1518–1585).

- Francis James Newman Rogers (1791–1851).

- John Selden (1584 – 1654), English jurist

- James Simpson (1737–1815), Attorney General of Colonial South Carolina. His wife, who predeceased him, is buried in the South Transept of Westminster Abbey.[40]

- Sir John Tremayne (1647–1694).[41]

- Robert de Veteripoint, Sheriff of Westmoreland (died 1228).

See also

- List of churches and cathedrals of London

- Temple (Paris) – medieval Knights Templar European headquarters

- History of Medieval Arabic and Western European domes

References

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Inner Temple Library website (retrieved 10 August 2018)

- "FOUNDATION-THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR". Temple Church. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Archives of the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, TEM: Records of administration [sic] of the Temple Church (1613–1996)

- "The Round Church". Temple Church. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Amanda Ruggeri (13 May 2016). "The hidden world of the Knights Templar". BBC Travel. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "The London Encyclopaedia" Hibbert, C; Weinreb, D; Keay, J: London, Pan Macmillan, 1983 (rev 1993, 2008) ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5

- The effigies are not in their original places

- The Old Churches of London Cobb, G: London, Batsford, 1942

- "London:the City Churches" Pevsner, N/Bradley, S New Haven, Yale, 1998 ISBN 0-300-09655-0

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- Service Sheet Archived 28 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Lewer, David (1961). A Spiritual Song, The Story of the Temple Choir & a History of Divine Service in the Temple Church, London, The Templar's Union, ASIN B0014KQ33I

- ''When A Knight Won His Spurs by Libera (soloist: Ben Crawley); LiberaUSA, 2006 (Youtube). See also: Hever Castle and Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon.

- Hans Zimmer Making of "Interstellar" Soundtrack (2014)

- "The National Pipe Organ Register - NPOR". www.npor.org.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Temple Church Choir website Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Who's Who". www.templechurch.com. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "Temple Church". The Inner Temple Library. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Barnes, John (1979). Ahead of his Age: Bishop Barnes of Birmingham. Collins. p. 76. ISBN 0-00-216087-0.

- Bellot, Hugh H.L. (1902). The Inner and Middle Temple: Legal, Literary and Historical Associations. London: Methuen & Co. page 231

- Foster, Joseph (1891). Alumni Oxonienses: Balgay, Nicholas. 1. p. 61. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "Master, Thomas (MSTR573T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Micklethwayte, Paul (MKLT606P)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Master of New Temple". Journal of the House of Commons. 3: 596–598. 19 August 1644.

- Inderwick, F. A., ed. (1898). A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records. 2. pp. ciii–civ. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Inderwick, F. A., ed. (1898). A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records. 2. pp. civ–cv. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Inderwick, F. A., ed. (1898). A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records. 2. pp. cxxii–cxxiii. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "Ball, Richard (BL623R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- "Nicolls, Samuel (NCLS731S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Sharpe, Gregory (SHRP735G)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Watts, George (WTS718G)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Foster, Joseph. . – via Wikisource.

- "Pearce, William (PR763W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Kipling, Thomas (KPLN764T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Rennell, Thomas (RNL773T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Benson, Christopher (BN804C)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Griffith-Jones, Robin; Park, David, eds. (2010). The Temple Church in London: History, Architecture, Art. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84383-498-4.

- James Riley Hill, III (1992), An Exercise in Futility: The Pre-Revolutionary Career and Influence of Loyalist James Simpson [unpublished M.A. thesis], Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina, OCLC 30807526.

- Stuart Handley (May 2009). "Tremayne, Sir John (bap. 1647, d. 1694)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27692. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple Church, London. |

- Official website of the Temple Church

- Official website detailing the music of the Temple Church

- Middle Temple's website

- Inner Temple's website

- 2008 Temple Festival website

- Temple Church – Sacred Destinations article with large photo gallery

- Black and white images of the Temple – Pitt University

- Ground plan and discussion of round shape – Rosslyn Templars

- The History of the Knights Templar, by Charles Greenstreet Addison, with extensive history and description of Temple Church

.svg.png.webp)