Terqa

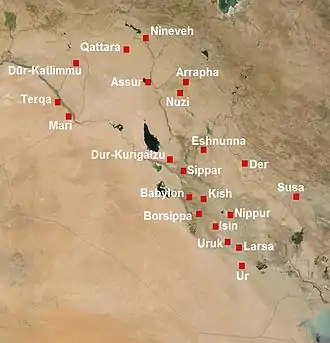

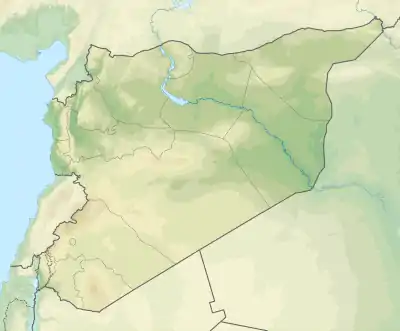

Terqa is the name of an ancient city discovered at the site of Tell Ashara on the banks of the middle Euphrates in Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria, approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the modern border with Iraq and 64 kilometres (40 mi) north of the ancient site of Mari, Syria. Its name had become Sirqu by Neo-Assyrian times.

Shown within Near East  Terqa (Syria) | |

| Location | Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Deir ez-Zor Governorate |

| Coordinates | 34°55′24″N 40°34′10″E |

| Mari |

Euphrates • Terqa • Tuttul Royal Palace |

| Kings |

| Yaggid-Lim • Yahdun-Lim Yasmah-Adad Zimri-Lim (Queen Shibtu) |

| Archaeology |

| Investiture of Zimri-Lim Statue of Ebih-Il Statue of Iddi-Ilum |

History

Little is yet known of the early history of Terqa, though it was a sizable entity even in the Early Dynastic period.

In the 2nd millennium BC it was under the control of Shamshi-Adad, followed by Mari in the time of Zimri-Lim, and then by Babylon after Mari's defeat by Hammurabi of the First Babylonian dynasty, Terqa became the leading city of the kingdom of Khana after the decline of Babylon. Later, it fell into the sphere of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon and eventually the Neo-Assyrian Empire. A noted stele of Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta II was found at Terqa.[1]

The principal god of Terqa was Dagan.

Proposed Rulers of Terqa

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Yapah-Sumu | circa 1700 | |

| Isi-Sumu-Abu | ||

| Yadikh-Abu | Contemporary of Samsu-iluna of Babylon, 7 year names known | |

| Kastiliyasu | 4 year names known | |

| Sunuhru-Ammu | 4 year names known | |

| Ammi-Madar | 1 year name known | |

| Isar-Lim | 1 year name known | |

| Yaggid-Lim | ||

| Iish-Dagan | 1 year name known | |

| Hammurapih | 3 year names known | |

| Parshatatar | Mitanni king | |

Archaeology

The main site is around 20 acres (8.1 ha) in size and has a height of 60 feet (18 m). The remains of Terqa are partly covered by the modern town of Ashara, which limits the possibilities for excavation.

The site was briefly excavated by Ernst Herzfeld in 1910.[2] In 1923, 5 days of excavations were conducted by François Thureau-Dangin and P. Dhorrne.[3]

From 1974 to 1986, Terqa was excavated for 10 seasons by a team from the International Institute for Mesopotamian Area Studies including the Institute of Archaeology at the University of California at Los Angeles, California State University at Los Angeles, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Arizona and the University of Poitiers in France. The team was led by Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati.[4][5][6] After 1987, a French team led by Olivier Rouault of Lyon University took over the dig and continues to work there to the present time.[7] [8][9]

There are 550 cuneiform tablets from Terqa held at the Deir ez-Zor Museum.

Notable features found at Terqa include

- A city wall consisting of three concentric masonry walls, 20 feet (6.1 m) high and 60 feet (18 m) in width, fronted by a 60-foot-wide (18 m) moat. The walls encompass a total area of around 60 acres (24 ha), were built circa 3000 BC and were in use until at least 2000 BC.

- A temple to Ninkarrak dating at least as old as the 3rd millennium. The temple finds included Egyptian scarabs.[10]

- The House of Puzurum, where a large and important archive of tablets were found.

Genetics

Ancient mitochondrial DNA from freshly unearthed remains (teeth) of 4 individuals deeply deposited in slightly alkaline soil of ancient Terqa and Tell Masaikh (ancient Kar-Assurnasirpal, located on the Euphrates 5 kilometres (5,000 m) upstream from Terqa) was analysed in 2013. Dated to the period between 2.5 Kyrs BC and 0.5 Kyrs AD the studied individuals carried mtDNA haplotypes corresponding to the M4b1, M49 and M61 haplogroups, which are believed to have arisen in the area of the Indian subcontinent during the Upper Paleolithic and are absent in people living today in Syria. However, they are present in people inhabiting today’s India, Pakistan, Tibet and Himalayas.[11]

See also

Notes

- H. G. Güterbock, A Note on the Stela of Tukulti-Ninurta II Found near Tell Ashara, JNES, vol. 16, pp. 123, 1957

- E. Herzfeld, Hana et Mari, RA, vol. 11, pp. 131-39, 1910

- François Thureau-Dangin and P. Dhorrne, Cinq jours de fouilles à 'Ashârah (7-11 Septembre 1923), Syria, vol. 5, pp. 265-93, 1924

- G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 1: General Introduction and the Stratigraphic Record of the First Two Seasons, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol 1, no.3, pp. 73-133, 1977

- G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 6: The Third Season: Introduction and the Stratigraphic Record, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol 2, pp. 115-164, 1978

- Giorgio Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 10: The Fourth Season: Introduction and Stratigraphic Record, Undena, 1979, ISBN 0-89003-042-1

- Olivier Rouault, Mission archéologique à Ashara-Terqa (Syrie) : note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2005, S.l., 2004

- Olivier Rouault, Projet Terqa et sa région (Syrie) : mission archéologiques à Terqa et à Masaïkh, recherches historiques et épigraphiques ; rapport final de la saison 2001 ; note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2003, S.l., 2002

- Olivier Rouault, Projet Terqa et sa région (Syrie) : recherches à Terqa et dans la région, année 2001 ; note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2002, S.l., 2001

- R. M. Liggett, Ancient Terqa and its Temple of Ninkarrak: the Excavations of the Fifth and Sixth Seasons, Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin, NS 19, pp. 5-25, 1982; see now also: A. Ahrens, The Scarabs from the Ninkarrak Temple Cache at Tell ’Ašara/Terqa (Syria): History, Archaeological Context, and Chronology, Egypt and the Levant 20, 2010, 431-444

- Witas, Henryk W.; Jacek Tomczyk; Krystyna Jędrychowska-Dańska; Gyaneshwer Chaubey & Tomasz Płoszaj (2013) "mtDNA from the Early Bronze Age to the Roman Period Suggests a Genetic Link between the Indian Subcontinent and Mesopotamian Cradle of Civilization"; PLOS ONE, September 11, 2013. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073682.

References

- A. Ahrens, The Scarabs from the Ninkarrak Temple Cache at Tell ’Ašara/Terqa (Syria): History, Archaeological Context, and Chronology, Egypt and the Levant 20, 2010, 431-444.

- G. Buccellati, The Kingdom and Period of Khana, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 270, pp. 43–61, 1977

- M. Chavalas, Terqa and the Kingdom of Khana, Biblical Archaeology, vol. 59, pp. 90–103, 1996

- A. H. Podany, A Middle Babylonian Date for the Hana Kingdom, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 43/45, pp. 53–62, (1991–1993)

- J. N. Tubb, A Reconsideration of the Date of the Second Millennium Pottery From the Recent Excavations at Terqa, Levant, vol. 12, pp. 61–68, 1980

- A. Soltysiak, Human Remains from Tell Ashara - Terqa. Seasons 1999-2001. A Preliminary Report, Athenaeum, 90, no. 2, pp. 591–594 2002

- J Tomczyk, A Sołtysiak, Preliminary report on human remains from Tell Ashara/Terqa. Season 2005, Athenaeum. Studi di Letteratura e Storia dell’Antichità, vol. 95 (1), pp. 439-441, soo7