The Children of Peace

The Children of Peace (1812–1889) was an Upper Canadian Quaker sect under the leadership of David Willson, known also as 'Davidites', who separated during the War of 1812 from the Yonge Street Monthly Meeting in what is now Newmarket, Ontario, and moved to the Willsons' farm. Their last service was held in the Sharon Temple in 1889.

| Part of a series on the |

| Quakers in Canada |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Meetings |

|

|

Between 1825 and 1832, a series of buildings was constructed on the farm, the most notable of which is the Sharon Temple, an architectural symbol of their vision of a society based on the values of peace, equality and social justice, which is now part of an open-air museum that was in 1990 designated as National Historic Site of Canada.

They were a "plain folk", former Quakers with no musical tradition, who went on to create the first silver band in Canada and build the first organ in Ontario.[1] They built an ornate temple to raise money for the poor, and built the province's first shelter for the homeless.[2] By 1851, Sharon Temple was the most prosperous agricultural settlement in the province. They took a lead role in the organization of the province's first co-operative, the Farmers' Storehouse, and opened the province's first credit union.[3] Through their support of William Lyon Mackenzie, and by ensuring the elections of both "fathers of responsible government", Robert Baldwin and Louis LaFontaine, they played a critical role in the development of democracy in Canada.[4]

The Children of Peace ('Davidites')

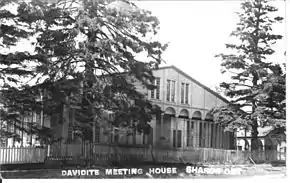

The group is primarily associated with the community of Hope (now Sharon) in East Gwillimbury, York Region, Ontario, where they built their meeting houses (places of worship) and the Temple. They were also active throughout the old "Home District" and especially in Toronto. Although they never numbered more than 350 members, Reform politician and Rebellion leader William Lyon Mackenzie noted, “they afford ample proofs, both in their village and in their chapels, that comparatively, great achievements may be accomplished by a few when united in their efforts and persevering in their habits.”[5]

The Temple was constructed from 1825 to 1832. It was constructed in imitation of Solomon's Temple and the New Jerusalem described in Revelation 21, and once a month collected alms for the poor. Two other meeting houses in the village of "Hope" were used for regular Sunday worship. The Children of Peace, having fled a cruel and uncaring English "pharaoh," viewed themselves as the new Israelites lost in the wilderness of Upper Canada; here they would rebuild God’s kingdom on the principle of charity. The village of “Hope” was their new Jerusalem, the focal point of God’s kingdom on earth. Many came to Canada from the United States.

Leadership

The leader of this group was David Willson, who was born of Presbyterian parents in New York State in 1778 and migrated to Canada in 1801. He joined the Quakers, of which his wife was a member, but his ministry was rejected when he began to preach at the beginning of the War of 1812. Willson was particularly concerned with taking up the Society's peace testimony "from where George Fox left it, and raise it so high, that all the Kingdoms of the Earth should see it."[6] He was joined by a majority of the Quakers living on Yonge Street, including the Master Builder of the Temple and meeting houses, Ebenezer Doan whose home now stands on the grounds of the Sharon Temple.[7] Doan’s farmhouse and out-buildings now stand on the Sharon Temple Museum grounds. Samuel Hughes (Children of Peace), another leading member, played a large role in the development of the Farmers’ Storehouse, and reform politics.

The village of Hope and its cooperative economy

In 1828, William Lyon Mackenzie visited Hope for the first time, describing it as a “village composed of about forty or fifty remarkably neat, clean dwellings; but what gives the most imposing effect is, the handsome newly built Temple, which is built nearly on the summit of the hill, and is now nearly finished. It is intended for their public worship, and is built somewhat after the manner of Solomon's Temple. The new church or chapel of the Children of Peace is certainly calculated to inspire the beholder with astonishment; its dimensions - its architecture - its situation - are all so extraordinary.”[8] The consolidation of the Children of Peace in a single village, Hope, was accompanied by their adoption of a cooperative economy. Through cooperative marketing, the establishment of a credit union, and a land-sharing system, the Children of Peace all became prosperous farmers in an era when new farmers frequently failed. The Children of Peace were never communal like many of the other new religious movements then sprouting up in the United States (like the Shakers, the early Mormons or the Oneida Perfectionists). The Children of Peace viewed trade as a necessarily moral act; in selling their wheat they were not concerned simply with obtaining the "highest market price." Since they did not have to calculate for profit, the logic of their commercial exchanges was based on moral principles, not economic ones. David Willson urged the members of his sect not to bargain at all, but to seek a fixed price that represented their own needs, rather than the highest amount the market would bear.[9]

Soon after they completed their temple and began collecting alms there, members of the Children of Peace complained that the remainder of the unspent Charity Fund was “a loss of interest obstructing to benevolence and makes money useless like the misers’ store.”[10] The Children of Peace began using the same fund for both gifts of charity as well as for loans to members. Those members who borrowed from the Charity Fund paid interest, transforming the fund into an endowment for further charity (and further loans) like today's Community Foundations. Since they controlled the loan process themselves, they could ensure that terms were manageable, that no one was denied credit, and that the repayment of the principal remained flexible in difficult times. Members of the Children of Peace took a lead role in a similar joint stock company, the Farmers’ Storehouse, Canada’s first farmers’ co-operative, which also began to offer loans to members in this period.[11]

Political contributions

Although captivated by visions of equality, the Children of Peace lived in an autocratic colony. They inspired other settlers to fight for democracy within a loose-knit "Reform Movement" of disenchanted farmers and tradesmen. David Willson had long been an active political figure. He had, for example, suggested the “General Convention of [Reform] Delegates,” which was then held in February 1834 to nominate candidates for the four ridings of the County of York.[12] This was the foundation on which the Canadian Alliance Society (the first political party in the province) was erected; these candidates were required to pledge in advance to fight for a democratic reform platform in the House. David Willson was the main speaker before the convention and “he addressed the meeting with great force and effect”.[13]

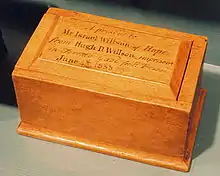

William Lyon Mackenzie was the elected representative of their riding. He eventually attempted to overthrow the government in the Rebellion of 1837. Some of the Children of Peace, including Willson’s sons and son-in-law, participated. The events and consequences of the rebellion are well known: the skirmish at Montgomery's Tavern, the hanging of Samuel Lount, Lord Durham's Report, political reform and Responsible Government (Cabinet rule). Less well known is the tedium of the jail cell in harsh winter conditions endured by many of the rebels. To while away the long hours, many prisoners carved small, ornate boxes as presents for their families. The boxes memorialize friends lost in battle, and express a defiant call for liberty and democracy. They were the sole consolation for those who had been widowed, or whose husbands remained in jail; for example, David Willson’s daughter, a pregnant Mary Willson Doan, wrote to her husband in jail telling him her wish, that "you would be permitted to come to your little home”, acknowledging the reality, and desiring a “box” for her yet unborn child. That child, David Willson Doan, was born twelve days after the letter was written. Charles Doan remained in jail for a further five months.[14]

In the wake of the Rebellion, the Children of Peace resisted Orange Order violence in the pursuit of democratic reform. Many members took part in a "Durham Meeting" in 1838 in which the Orange Order attacked the crowd with clubs, and in the melee a 19-year-old member of the Children of Peace, David Leppard, was killed when struck with a rock to his temple. Leppard’s death became a rallying point for Reformers across the province. Everyone knew who was responsible for his death. The Sheriff, William Jarvis, had egged on the Orange Order, and George Duggan Jr., a Toronto Alderman and Orange Order organizer had directed the mob. Yet no arrests were made. There was no inquiry into the death. And no-one could hope for justice when the Sheriff himself – one of the co-accused – was responsible for picking the jurors at a trial.

During the 1840s, Willson continued his association with the Reform Party; he was, for example, the campaign manager in the area for both Robert Baldwin and Louis LaFontaine, the “Fathers of Responsible Government” and first elected premiers of the province. It was the Children of Peace who ensured the election of Montreal lawyer Louis LaFontaine as their representative in Upper Canada. Willson argued that this was an opportunity, as he said, “to show our impartial respect to the Canadian people of the Lower province.” Here, Willson is expressing a clear Canadian identity which overcame differences in language and religion. It was a vision of Canadian citizenship that was ultimately successful, with LaFontaine's election in the 4th Riding of York.[15] Subsequently, they elected Baldwin in their riding. The silver band of the Children of Peace was a familiar sight at Baldwin's campaign rallies. In 1844, they held a campaign rally for Baldwin concurrent with the illumination of the Temple. More than 3000 people attended, and the event helped end the reign of Orange Order electoral violence.[16]

Religious life

Meeting houses

The Temple is calculated to inspire the beholder with astonishment; its dimensions—its architecture—its situation—are all so extraordinary.

— W. L. Mackenzie 18 September 1828

Most of the meeting houses of the Children of Peace are attributed to Master Builder Ebenezer Doan.

The first meeting house of the Children of Peace was built in 1819 on David Willson’s farm. It was square, forty feet (12.2 m) to each side, and sixteen feet (4.9 m) high. With one of Coates’s organs installed in 1820, the building acquired its more popular name, the Music Hall.

By far the best known of their buildings was the Temple, now a national historic site. The Temple's design is loosely based on a description of Solomon's Temple found in 1 Kings, chapter 6 and the New Jerusalem described in Revelation 21. The building was undertaken after Willson had a vision in which he was called "To ornament the Christian Church with all the glory of Israel." Preparation for the construction would have begun in 1822, with actual construction taking place between 1825 and 1831. A symbolic seventh year was taken to build the "ark" at its centre. The building was three stories high; the first was an auditorium, built without a pulpit, and the second floor was a musician's gallery reached by a curved staircase, "Jacob's Ladder." The Temple was used only once a month for an alms collection, again at Christmas, and for two special "Illumination" ceremonies in which its 2,952 panes of glass were set aglow.

David Willson's Study was completed in September 1829. Its exterior colonnade and arches can be seen as the Temple “turned inside out”. It was also referred to as "the counting house" and was no doubt the office in which Willson wrote his many books, and operated the "Farmer's Storehouse."

The second meeting house was three times the size of the first. Its design was based on David Willson’s study. Construction began in 1834 and completed in 1842. The building was 100 ft. long by 50 ft. wide surrounded by a colonnade of pillars. This building was painted a light yellow with green facings, and had a large room upstairs for Sabbath Schools, and band rehearsals. The main part of the building which was used for services.[17]

Theology

As an offshoot of the Society of Friends, the Children of Peace shared most Quaker belief, especially in the innate presence of God (the "inner light") in every person. Like the Quakers, they practiced a spontaneous ministry, and eschewed a "hireling clergy." David Willson was thus never their paid minister, and he never, in fact, entered the Temple during the monthly alms ceremony there. Like the Quakers, they also rejected any written creed or tests of faith: "We have no written creed, and therefore we have no image to quarrel about, or literal rule to argue for, we are against nobody, but for all."[18]

Willson, however, did receive "impressions on the mind", visions calling him to "ornament the Christian Church with the glory of Israel." He interpreted this as a call to rebuild Solomon's Temple as the new Jerusalem. During the 1830s, his preaching became more millenarian, prophesying the coming of a Messiah who would overthrow the British empire and establish God's kingdom on earth. He viewed his small group as the new Israelites lost in the wilderness of Upper Canada, whom the new Messiah would come to lead.[19]

After the Rebellion of 1837, the sect lost many of the more distinctive theological features which marked its early stages.

Music

Among the Protestant nominations, the Quakers were distinct for their rejection of music in worship. They argued that congregational singing was an empty form, and hence worshipped in silence until someone was moved to spontaneous ministry. David Willson, in contrast, began to "sing in the ministry" as early as 1811. He regarded music as another facet of the ministry, a spontaneous expression of God's word. Many early members left the Quakers because they wanted to play music. Willson was to boast, "I never repeat one communication twice over, nor sing one old hymn in worship: bread from heaven is our lot - descending mercies."[20] The constant production of new hymn lyrics, like manna from heaven, "were composed to suit the occasion on which they were sung."[21] These hymns, eventually numbering in the thousands, were recorded in a special "Book of Sacred Record" stored in a secret compartment in the Arc at the centre of the Temple and not discovered until recently. At the beginning and end of each worship service, Willson would "read out" a hymn, line by line, which would then be sung back by the choir, and then the congregation. The lining out of hymns had been the traditional singing style of the 18th century, when hymn books were expensive and rare. Songs were sung a cappella, resulting in slow, improvised singing in which each singer was allowed to decorate the tunes as he or she saw fit.[22]

Many of the Quakers who joined the Children of Peace were skilled craftsmen, but the Quaker “testimony” on plainness discouraged them from embracing the arts; adornment of any kind was considered little but a sign of pride. Thus, when David Willson’s vision commanded him to “ornament the Church with all the glory of Israel,” the sect had to turn to an outsider, Richard Coates, for guidance. Coates, a former British Army Bandmaster, exerted tremendous influence on the art and music by which the Children of Peace came to be known outside their community. Coates was commissioned by the Children of Peace to build the first of their organs — said, in fact, to be the first built in Ontario; it sat on an elevated platform in the first meeting house. This was a "barrel organ", in effect, a large music box played by turning a handle. It is thus also potentially the first music recording made in Canada.[23]

It was at this time that Coates gave lessons to the Children of Peace in the rudiments of musical performance, teaching members how to play the instruments of a brass band. The band sat under the platform on which the organ played. He also painted “the symbolic decorations of the interior of the Temple at Sharon,” and painted the banners they carried in front of their processions. He also organized a choir of “virgins” (schoolgirls). The musical accompaniment provided by the choir, band and organs was in large part responsible for the fame — or infamy — which accrued to the Children of Peace. One Anglican clergyman in nearby Thornhill scathingly described them in the early 1830s: "King David (Willson) frequently goes to a great distance, in order to edify the people of other townships by his music and eloquence... He never performs such religious errantry without being accompanied by his virgins, six in number, selected from among the females of his household, for their superior voices. These virgins are conveyed in the same wagon with himself over which there is an awning, to shelter them from the inclemency of the weather, and from sultry rays. In one of the other wagons follow as many youths, who form an accompaniment to the damsels, and swell the anthems and hosannahs by vocal and instrumental music. In the remaining wagon are transported... their musical instruments... He never fails to attract a large assemblage of people... The music of his sacred band is considered curious; and the oddity of his manner, and his condemnation of the Established Church, and of the government, are approved by many."[24]

In 1846, the Children of Peace hired Daniel Cory, a music teacher from Boston, to teach them the unison singing style of the mainstream, and Willson produced three books of hymns for the members.

The largest of the organs built by Coates was a keyboard organ (now in the Temple) completed in 1848 for the second meeting-house. The organ stood against the back wall of the second meeting-house between the two rear doors. It stands about fourteen feet (4.3 m) high, housed in an impressive case assembled in three towers; to the front are three semi-circles of gilded dummy pipes which hide the wooden pipework within. The organ has a manual 49-note direct mechanical keyboard, four drawstops, and 200 wooden flue pipes in four ranks. A manual bellows is pumped from the left side.

The Sharon Silver (or Temperance) Band was formed after a set of silver instruments was purchased in Boston for a reputed $1,500 in the 1860s. The bandleaders were Jesse Doan and from 1866 his nephew John Doan Graham. They wore blue uniforms and on occasion appeared on Lake Simcoe steamers and in Toronto.[25] Descendants have recounted stories of the silver band's travel to the U.S. to attend musical events and that Jesse Doan could listen to a piece of music once, return to his hotel room and write down all the musical notes.

Schools and education

Soon after they separated from the Society of Friends in 1812, the Children of Peace established their first school; a boarding school taught by William Reid, "a man of more than ordinary intellect" with "an excellent English education." One of Willson's first books was a "Lesson of Instruction", a reader on the group's distinctive beliefs for this school. The school was eventually known as "the female institution" after it was moved to Sharon. A day school for boys and girls was also opened. The boarding school was housed in a two storey "Square House" with David Willson and his wife Phebe as caretakers. The boarding school for girls was a bulwark of the community, and the young girls formed the sect's choir. The day school eventually moved into quarters on the second floor of the second meeting house.[26]

Dissolution

1851 represents the apogee of the community of Hope (Sharon). Their cooperative economy, their concern for charity and the equal prosperity of all, made them the most prosperous agricultural community in the entire province; substantial farmhouses now dotted the surrounding landscape. Their political influence was at its peak, with deep long-standing ties to both Baldwin and LaFontaine. But age was taking its toll on the village’s patriarch, David Willson, now in his seventies. He remained their only minister until his death in 1866, their numbers slowly dwindling. Willson’s son, John David Willson, led the Children of Peace thereafter, reading his father’s sermons to an aging congregation. Ministers from other denominations were gradually invited to preach in their meeting houses. In 1876, they incorporated as a “charitable society.” In 1889, after the death of Willson’s sons, the group ceased to exist, and the Temple was allowed to fall into ruins.[27] The last service was held in the Temple in 1889. The derelict Temple was purchased by the York Pioneer and Historical Society in 1917, and restored, making it one of the earliest examples of historic preservation in Canada. The temple is now a National Historic Site and Museum as well as a National Peace Site. The site has a collection of restored buildings and displays pioneer artefacts and historic items related to the sect.

References

- Schrauwers, Albert (1993). Awaiting the Millennium: The Children of Peace and the Village of Hope 1812-1889. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 71–72.

- Sharon Temple, On-line Exhibition

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 97–124.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–149, 211–243.

- Colonial Advocate. 18 September 1828. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sharon Temple Museum. "OSHT 990.1.2": 17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Schrauwers, Albert (1993). Awaiting the Millennium: The Children of Peace and the Village of Hope 1812-1889. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 18.

- Mackenzie, William Lyon (1833). Sketches of Canada and the United States. E. Wilson. pp. 120.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 41–49, 115–8.

- Ms 733, Series A, page 7, Committee Records. Ontario Archives. 29 September 1832.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 97–124.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 135–8.

- Colonial Advocate. 20, 27 February 1834. Check date values in:

|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Schrauwers, Albert (1987). "Letters from Prison". The York Pioneer: 25–35.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength: W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 211–243.

- McArthur, Emily (1898). Children of Peace. Newmarket: Era & Express. p. 5.

- Willson, David (1831). unnamed pamphlet written on the completion of the Temple. p. 8.

- Willson, David (1835). Letters to the Jews. Toronto.

- Willson, David (1835). Impressions of the Mind. Toronto: J.H. Lawrence. p. 254.

- Colonial Advocate. 3 Sep 1829. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Schrauwers, Albert (1993). Awaiting the Millennium: The Children of Peace and the Village of Hope 1812-1889. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 65–66.

- "Children of Peace". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Fidler, Isaac (1832). Observations on Professions, Literature, Manners and Emigration, in the United States and Canada, Made during a Residence there in 1832. London. pp. 325–6.

- McArthur, Emily (1898). Children of Peace. Newmarket: Era & Express. p. 12.

- Schrauwers, Albert (1993). Awaiting the Millennium: The Children of Peace and the Village of Hope, 1812-1889. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 74–77.

- McFall, Jean (1973). "The Last Days of the Children of Peace". The York Pioneer. 68: 22–33.

External links

- Rebuilding Hope: Celebrating our social-democratic heritage

- Sharon Temple National Historic Site

- The History of the Battle of Toronto by William Lyon MacKenzie, 1839 from the Ontario Time Machine

Further reading

- McIntyre, William John; Children of Peace (Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press, 1994).