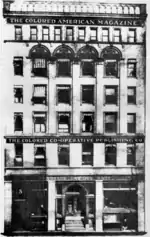

The Colored American Magazine

The Colored American Magazine was the first American monthly publication that covered African-American culture. The magazine ran from May 1900 to November 1909. It was initially published out of Boston by the Colored Co-Operative Publishing Company, and from 1904, forward, by Moore Publishing and Printing Company of New York. Pauline Hopkins, its most prolific writer from the beginning, sat on the board as a shareholder, was editor from 1902 to 1904, though her name was not on the masthead until 1903. Hopkins was a journalist, playwright, historian, and literary. In 1904, Booker T. Washington, in a hostile takeover, purchased the magazine and replaced Hopkins with Fred Randolph Moore (1857–1943) as editor.[1]

The Colored American, February 1901 | |

| Editor | Fred Randolph Moore (1857–1943) |

|---|---|

| Former editors | Pauline Hopkins |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Format | |

| Founder | Pauline Hopkins (1859–1930) |

| Year founded | 1900 |

| Final issue | 1909 |

| Company | Colored Co-Operative Publishing Company |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Boston (1900–1004) New York (1904–1909) |

| Language | English |

| OCLC | 1564200 |

History

The Colored American Magazine was founded by Walter Wallace, Jesse W. Watkins, Harper S. Fortune, and Walter Alexander Johnson. The holding company was named The Colored Co-Operative Publishing Company. Around 1902, the magazine operated from headquarters in Boston's Park Square, adjacent to the Boston Common. On May 13, 1903, William H. Dupree (1839–1934), and Jesse W. Watkins purchased the magazine from the Colored Co-operative Publishing Company and renamed the holding company The Colored American Publishing Company. Their aim was to redeem the magazine, financially, and to secure its location in Boston with Hopkins as editor.[2][3]

Post-1996 findings relating to Pauline Hopkins

John C. Freund (1848–1924), London-born and Oxford educated co-founder and influential editor of two New York magazines, The Music Trades and Musical America, became an outside investor in the magazine in 1903. Recently, beginning around 1996, after the rediscovery of 20 letters in the Pauline Hopkins Collection at the Fisk University Library,[4] scholars show that Hopkins sensed that Freund had conspired with Booker T. Washington to replace her as editor — to quell her outspokenness on racial matters, which in that era, was a prevailing taboo in the minds of many whites. Freund, a white man, and Washington, an African American man, prevailed against Hopkins, an African American woman. The letters reveal that Hopkins, a well-articulated and influential editor, was a victim of sexism and nuanced racism that was masked by the enlisted cooperation of Washington. Freund apparently believed, and perhaps Washington believed, that directness, about race issues, and racial activism by the magazine would do more harm than good — it would generate greater racial discord in society, harm the economic viability of the magazine, drive away white readership, marginalize the potential for the magazine to win support of whites who otherwise harbored cynical views towards racial equality.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] Freund felt that the goal of the magazine was to "first—record the work the colored people are doing; second—to make the whites acquainted with it." Freund opposed writers who felt that advancing bravely required historic retrospection.[16] In other instances, Freund had rallied support towards helping African Americans succeed and he patronized those who had attained success, which included financial support and published critical acclaim for the People's Chorus, directed by Emma Azalia Hackley (1867–1922). The upshot was that Hopkins believed, as documented in her letters, that Freund's altruistic gestures towards helping her and the magazine were actually a ploy to oust her and take control of the magazine's political content. There are differing views on Freund and Washington's motives, and differing views on who led the charge, but there is little debate on how Hopkins perceived it..

See also

References

- "Moore, Fred Randolph", Henry Louis Gates, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (eds), The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Literary Renaissance, Facts on File (2006); OCLC 56599564

- Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Maberry Johnson, Propaganda and Aesthetics: The Literary Politics of African-American Magazines in the Twentieth Century, University of Massachusetts Press (1991), p. 9; OCLC 44954595

- Donald Franklin Joyce, Black Book Publishers in the United States: A Historical Dictionary of the Presses, 1817–1990, Greenwood Press (1991), p. 81; OCLC 65333123

- Pauline Hopkins Collection, 1879-1899, Fisk University Library Special Collections, Nashville; OCLC 70972578

- Hanna Wallinger, PhD, Pauline E. Hopkins: A Literary Biography, University of Georgia Press (2005), pp. 80–84; OCLC 794449222

- Special collections at the Library of Congress: Hanna Wallinger, , "Pauline E. Hopkins: a Literary Biography", University of Georgia Press (2005); OCLC 794449222

- Alisha Renee Knight, PhD (born 1976), Pauline Hopkins and the American Dream: An African American Writer’s (Re)Visionary Gospel of Success, University of Tennessee Press (2012), p. 28; OCLC 780445267

- Lois A. Brown, PhD (born 1966), Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution, University of North Carolina Press (2008), p. 423; OCLC 181142292

- John Cullen Gruesser, PhD, The Unruly Voice: Rediscovering Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins, University of Illinois Press (1996); OCLC 33014005

- The Colored American Magazine Correspondence folder, 20 Letters (19 from Freund to Hopkins), Fisk University Library Special Collections, Nashville.

- William R. Lee, "A New Look at a Significant Cultural Moment: The Music Supervisors National Conference 1907–1932," Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, Ithaca College , Vol. 18, No. 2, April 2007; ISSN 1536-6006

- Karpf, Juanita (2011). "Get the Pageant Habit: E. Azalia Hackley's Festivals and Pageants during the First World War Years, 1914–1918". Popular Music and Society. 34 (5): 517–556. doi:10.1080/03007766.2010.521441.

- Gretchen Murphy, PhD (born 1971), Shadowing the White Man's Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line, New York University Press (2010), pp. 128–136; OCLC 697175319

- Jessica Metzler, "Genuine Spectacle: Sliding Positionality in the Works of Pauline E. Hopkins, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Spike Lee" (master's thesis), Florida State University (2006); OCLC 70113691

- Jill Bergman, "'Everything We Hoped She'd Be,' Contending Forces in Hopkins Scholarship," African American Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, Summer 2004; OCLC 108247722, 5545148032, 5552642411 ISSN 1062-4783

- Sharon M. Harris & Ellen Gruber Garvey (eds), Blue Pencils & Hidden Hands: Women Editing Periodicals, 1830–1910, Northeastern University Press (2004), p. 169; OCLC 53846367

Further reading

- R.S.Elliott (May 1901). "The Story of Our Magazine". Colored American Magazine. 3 (1): 43–77 – via HathiTrust.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Colored American magazine. |