The House on 92nd Street

The House on 92nd Street is a 1945 black-and-white American spy film directed by Henry Hathaway. The movie, shot mostly in New York City, was released shortly after the end of World War II. The House on 92nd Street was made with the full cooperation of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), whose director, J. Edgar Hoover, appears during the introductory montage. Also, the FBI agents shown in Washington, D.C. were played by actual agents. The film's semidocumentary style inspired other films, including The Naked City and Boomerang.[2]

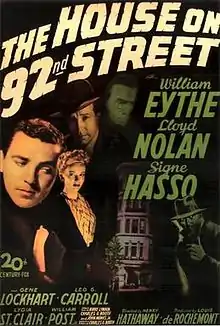

| The House on 92nd Street | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Henry Hathaway |

| Produced by | Louis De Rochemont |

| Screenplay by | Barré Lyndon Jack Moffitt John Monks Jr. |

| Story by | Charles G. Booth |

| Starring | William Eythe Lloyd Nolan Signe Hasso |

| Narrated by | Reed Hadley |

| Music by | David Buttolph |

| Cinematography | Norbert Brodine |

| Edited by | Harmon Jones |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.5 million[1] |

Plot

In 1939, American standout university student, Bill Dietrich, is approached by Nazi recruiters because of his German heritage. He feigns interest, then notifies the FBI. Agent George Briggs encourages Dietrich to play along. Thus, Dietrich travels to Hamburg, Germany, where he undergoes six months of intensive training in espionage. The Germans then send him back to the United States to set up a radio station on Long Island to relay secret information on shipping arrivals, departures, destinations, and cargo. Dietrich is also to act as paymaster to the spies already there and who meet regularly at a house on East 92nd Street in New York City. He is told that only a certain "Mr. Christopher" has the authority to alter the details of his assignment.

Dietrich passes along his microfilmed credentials as a Nazi agent to the FBI. Agents decide to alter his authorized status so that instead of being forbidden to contact most of the agents, he is authorized to meet all of them. The 92nd Street residence is actually a multi-storied building with a dress shop, serving as a front for German agents, on the first floor. His contact is dress designer Elsa Gebhardt. She reacts suspiciously to Dietrich's high degree of authority. She requests confirmation from Germany, but communication is slow. Thus, she has no choice but to allow Dietrich full access to her spy ring. When questioned, Dietrich's other legitimate contact, veteran espionage agent Colonel Hammersohn, denies knowing "Mr. Christopher's" identity.

In a separate development, a German spy is killed in a traffic accident; the FBI finds a secret message among his possessions stating that a "Mr. Christopher" will concentrate on Process 97. Briggs is alarmed because he is aware that Process 97 is America's most closely guarded secret—the atomic bomb project. And when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States enters the war. Most of the spies Dietrich has identified are immediately picked up, but the FBI purposely overlooks Gebhardt's ring and intend to do so until "Mr. Christopher's" identity is established.

While Gebhardt instructs Dietrich to transmit a key portion of Process 97 immediately to Germany, he notices a cigarette butt in non-smoker Gebhardt's otherwise empty ashtray. He surreptitiously secures the butt and sends it to the FBI, where agents trace the clue to Luise Vadja, and from her to her supposed boyfriend, Charles Ogden Roper, a scientist working on Process 97. Roper is picked up and questioned. He breaks while under interrogation and confesses to have hidden the last part of Process 97 in a copy of Spencer's First Principles at a bookstore from where a person believed to be "Mr. Christopher" had been filmed by agents. Briggs then orders the immediate arrest of Gebhardt's ring.

In the meantime, Gebhardt finally receives a reply from Germany, confirming her suspicions of not only Dietrich's limited authority but of his true loyalties. She injects him with scopolamine in an attempt to obtain information, but her building is surrounded by government agents. Gebhardt orders her underlings to hold them off while she disguises as a man—the elusive "Mr. Christopher"—and tries to sneak out with the final vital papers on Process 97 that she has just retrieved from the bookstore. Unable to climb down the fire escape, she returns, only to be accidentally shot by one of her own men. The rest are captured, and Dietrich is rescued.

Cast

- William Eythe as Bill Dietrich (based on FBI double-agent William G. Sebold)[3]

- Lloyd Nolan as Agent George A. Briggs

- Signe Hasso as Elsa Gebhardt (based on the spy Lilly Stein)[3]

- Gene Lockhart as Charles Ogden Roper (based on the spy Herman Lang) who delivered the top secret Norden bombsight to Germany)[3]

- Leo G. Carroll as Col. Hammersohn (inspired by the spy ring leader Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne)[3]

- Lydia St. Clair as Johanna Schmidt, part of Gebhardt's ring

- William Post Jr. as Walker (as William Post)

- Harry Bellaver as Max Cobura, one of Gebhardt's spies

- Bruno Wick as Adolf Lange, owner of the bookstore

- Harro Meller as Conrad Arnulf, another of Gebhardt's agents

- Charles Wagenheim as Gustav Hausmann

- Alfred Linder as Adolf Klein

- Renee Carson as Luise Vadja

- E.G. Marshall as Attendant at Morgue

- Elisabeth Neumann-Viertel as Freda Kassel

- Sheila Bromley as Beauty Parlor Customer

Production and background

The House on 92nd Street is the first film noir produced by Louis De Rochemont, credited as a pioneer of the semidocumentary style police thriller.[4]

TCM's host, Robert Osborne, said that the film is based on the real life case of William G. Sebold. He also said that they used real FBI agents and with real footage taken by the FBI.[5] Sebold was involved in bringing down the Duquesne Spy Ring in 1941, the largest convicted espionage case in the history of the United States. On January 2, 1942, 33 Nazi spies, including the ring leader Fritz Joubert Duquesne (also known as "The man who killed Kitchener"), were sentenced to more than 300 years in prison. One German spymaster later commented that the ring’s roundup delivered ‘the death blow’ to their espionage efforts in the United States. J. Edgar Hoover called his concerted FBI swoop on Duquesne's ring the greatest spy roundup in U.S. history.[6]

Lloyd Nolan would reprise his role as Inspector Briggs in the sequel, The Street with No Name (1948). In that film, Briggs and the FBI agents would take on organized crime. The actual house used in the filming of the movie stood at 53 E 93rd street. It is no longer there - it is now a pathway leading to premises behind the original house.

Reception

Critical response

Thomas M. Pryor, film critic for The New York Times wrote, "The House on Ninety-second Street barely skims the surface of our counterespionage operations, but it reveals sufficient of the FBI's modus operandi to be intriguing on that score alone."[7]

Although praised when released in 1945, the film, when released on DVD in 2005, received mostly mixed reviews. Christopher Null, writing for Filmcritic.com, writes, "Today, it comes across as a bit goody-goody, pandering to the FBI, pedantic, and not noirish at all."[8]

Accolades

Wins

- Academy Awards: Original Motion Picture Story — Charles G. Booth; 1946.

- Edgar Award: from the Mystery Writers of America for Best Motion Picture Screenplay - Charles G. Booth, Barre Lyndon, John Monks, Jr; 1945.

Radio adaptation

The House on 92nd Street was presented on Stars in the Air May 3, 1952. The 30-minute adaptation starred Humphrey Bogart and Keefe Brasselle.[9]

References

- Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 221

- The House on 92nd Street at the American Film Institute Catalog.

- Gevinson 1997, p. 470.

- Selby, Spencer. Dark City: The Film Noir, film listed as #178 on page 151, 1984. Jefferson, N.C. & London: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 0-89950-103-6.

- Osborne hosted the airing of the film on 22 May 2014 at 8:00 p.m. ET

- "Obituary. Fritz Joubert Duquesne". Time. June 24, 1956. ISSN 0040-781X.

- Pryor, Thomas. The New York Times, film review, September 27, 1945. Last accessed: February 8, 2010.

- Null, Christopher. Film review, 2005. Last accessed: February 8, 2010.

- "Those Were the Days". Nostalgia Digest. 35 (2): 32–39. Spring 2009.

- Bibliography