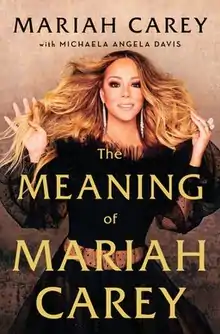

The Meaning of Mariah Carey

The Meaning of Mariah Carey is a memoir by Mariah Carey, released on September 29, 2020. The book was written with Michaela Angela Davis. Described as telling an "unfiltered story" of Carey's "improbable and inspiring journey of survival and resilience as she struggles through complex issues of race, identity, class, childhood, and family trauma during her meteoric rise to music superstardom,"[1] the memoir shared previously untold experiences.

| |

| Author | Mariah Carey Michaela Angela Davis |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Mariah Carey |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Memoir |

| Publisher |

|

Publication date | September 29, 2020 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover, paperback) Digital Audiobook |

| Pages | 368 (hardcover) 352 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-1-250-16468-1 |

| OCLC | 1157767321 |

| 782.42164092 | |

| LC Class | ML420.C2555 A3 2020 |

The book is published by Andy Cohen Books—an imprint of Henry Holt—and also available in an audiobook format on Audible. The audiobook version of the book, read by Carey herself, includes a variety of musical clips and interludes (also performed by Carey). The memoir became a #1 New York Times Best Seller after its first week of release.[2]

Background

Mariah Carey had considered writing a memoir since 2010 when she was pregnant with her twins Moroccan and Monroe.[3] In the two years prior to The Meaning of Mariah Carey's release, she told stories to co-writer Michaela Angela Davis. The book was first rumored in April 2018, and Carey acknowledged she was working on it during promotional appearances for her fifteenth studio album Caution (2018).[4][5] On July 9, 2020, she announced the memoir was complete.[6]

Contents

The book includes a preface and epilogue and is divided into four parts: "Wayward Child", "Sing. Sing.", "All That Glitters", and "Emancipation". It focuses on Carey's childhood, career, and personal and professional relationships, with less of a focus on events after 2001.

Plot summary

In "Wayward Child", Carey recounts being left alone, moving 13 times, and never feeling safe growing up. She details being exploited by her sister, Alison, fearing her brother Morgan, and feeling neglected by her mother, Patricia. It also discusses early experiences with racism and struggles with self-identity and self-worth.[7] During "Sing. Sing.", she recalls feeling trapped inside the mansion she lived in with her husband Tommy Mottola and being isolated from her fans. It also reveals what caused her to separate from and later divorce him and how she grew creatively as an artist.[8] "All That Glitters" details the events of Glitter (2001) and its accompanying soundtrack during which Carey felt betrayed by her family, "hunted" by tabloids, and scared of Mottola.[9] While attending therapy afterwards, "Emancipation" explains how she remains affected by trauma but grateful for her relationships with God and children Moroccan and Monroe.[10]

Excerpts

Alongside the plot, the inspirations and meanings of many of Carey's songs are explained and are often accompanied by excerpts from them.[11][12] Songs with lyrics interspersed between prose include "All in Your Mind" and "Alone in Love" from Mariah Carey (1990),[13][14] "Make It Happen" from Emotions (1991),[15] "Anytime You Need a Friend" and "Everything Fades Away" from Music Box,[16][17] "Hermit" from Someone's Ugly Daughter (1995),[18] "Looking In" and the remixes of "Fantasy" and "Always Be My Baby" from Daydream (1995),[19][20][21] "Honey", "My All", and "The Roof (Back in Time)" from Butterfly (1997),[22][23][24] "Can't Take That Away (Mariah's Theme)" from Rainbow (1999),[25] "Loverboy (Remix)" from Glitter (2001),[26] "Subtle Invitation" from Charmbracelet (2002),[27] "It's Like That" and "Fly Like a Bird" from The Emancipation of Mimi (2005),[28][29] "Bye Bye" and "I Wish You Well" from E=MC² (2008),[30][31] "Candy Bling" from Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel (2009),[32] and "Faded" from Me. I Am Mariah... The Elusive Chanteuse (2014).[33]

Chapters occasionally begin or end with lyrics from Carey's songs as epigraphs.[11] Parts of "Hero" from Music Box,[34] "All I Want for Christmas Is You" from Merry Christmas (1994),[35] "I Am Free" from Daydream,[36] "Close My Eyes" and "Outside" from Butterfly,[37][38] "Sunflowers for Alfred Roy" from Charmbracelet,[39] "Side Effects" and "Love Story" from E=MC²,[40][41] and "The Art of Letting Go" from Me. I Am Mariah... The Elusive Chanteuse open chapters,[42] while Rainbow's "Crybaby" and "Petals",[43][44] and Charmbracelet's "Through the Rain" and "My Saving Grace" close chapters.[45][46] Verses from the Bible are also incorporated in the memoir.[47][48][49]

Analysis

Media outlets noted that men associated with her such as Eminem,[4][50][51] former boyfriend Luis Miguel,[50] former fiancé James Packer,[51][52][53] and ex-husband Nick Cannon are absent or only receive brief mentions.[12][50][53] While she writes about an incident involving Jennifer Lopez, Carey does not name her.[51][52] Whitney Houston is not written about until 1998,[50][54] and her role as a judge on American Idol and feud with Nicki Minaj is unrecognized.[54] She explained: "If somebody or something didn't pertain to the actual meaning of Mariah Carey, as is the title, then they aren't in the book."[4]

Style and genre

Book reviews described the memoir as having an emphasis on the effects of Carey's experiences in her youth. While not only about hardship, Victoria Segal of The Sunday Times considered the book more serious than other gossip-oriented celebrity memoirs.[55] Writing for The Guardian, Alex Macpherson described it as "not the glitzy, gossipy celebrity reminiscence some might expect, but instead a largely sombre dive into her past that, at times, feels like therapy" due to the significant length about her traumatic childhood.[56] Cady Lang of Time agreed, regarding the inclusion of Carey's early relationship with Alison as "not a happy reminiscence on that time in her life, but instead a desire to heal from it".[57] According to Véronique Hyland of Elle, "the reality of living with a flawed past and coping with the present" is the central theme.[58] Noting its title is The Meaning of Mariah Carey—not The Making of Mariah Carey—Emily Lordi stated in The New Yorker that the book covers Carey's troubled youth more than her efforts to become successful.[11]

Despite the book's subject matter, critics thought it contained humor and elements of Carey's public image as a diva. Sentences often contain the word "dahlings", which is used to address the reader.[59][60][61] Referring to the passage "I really don't want a lot for Christmas—particularly not the cops", Macpherson stated "Carey recounts many of the worst parts of her life with a deadpan, self-aware wit",[56] and Segal said "she cracks enough jokes to suggest she would be great fun over an unguarded bottle of wine".[55] Kirkus Reviews wrote "Carey is at her best [in the memoir] when her outspoken personality shines through".[62] Citing comments about getting her hair done after the September 11 attacks and referring to Jennifer Lopez as "another female entertainer ... (whom I don't know)", Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone felt "every page is packed with her over-the-top personality".[54] As it is aided by her speaking voice, Hannah Reich of ABC News felt Carey's humor was pronounced in the audiobook version.[53]

Release and promotion

The Meaning of Mariah Carey was published on September 29, 2020, as one of the first releases by Andy Cohen Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company.[63] To promote the memoir, Carey spoke with Oprah Winfrey on an episode of her Apple TV+ show The Oprah Conversation during which she addressed the impact that her unique hair had as a young girl, her relationship with Derek Jeter, and finding emotional support from her children and fans.[64] She also discussed the book in several televised interviews on American morning and late-night talk shows. With Jane Pauley on CBS News Sunday Morning, Carey talked about her troubled childhood, marriage to Mottola, and the events of Glitter.[65] On CBS This Morning with Gayle King, she focused on the strained relationship with her mother.[66] Carey explained the purpose of writing the memoir and the process of recording the alternative rock album Someone's Ugly Daughter during an interview with Stephen Colbert on The Late Show.[67] On Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen and The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, she described early experiences with racism.[68][69] Carey was interviewed by Trevor Nelson on BBC Radio 2, describing the pervasiveness of sexism in the music industry and cherished relationships with her fans and children.[3][70] She also participated in a conversation with Misty Copeland for Amazon Live.[71]

Reception

Commercial performance

The Meaning of Mariah Carey debuted at number one on the weekly New York Times Best Seller list for both Hardcover Nonfiction and Combined Print & E-book Nonfiction.[72] On Publishers Weekly charts, the memoir entered at number three on Hardcover Frontlist Nonfiction and number six overall.[73][74] According to NPD BookScan, the memoir sold 62,557 units in its first three weeks of release in the United States.[75] In Canada, the book debuted at number three on both The Globe and Mail's Hardcover Non Fiction and the Toronto Star's Original Non-Fiction national bestseller lists.[76][77] It entered at number seven on The Sunday Times' General Hardbacks chart, selling about 6,940 copies in the United Kingdom.[78]

Critical response

Based on 11 reviews, aggregation website Book Marks reported a "rave" response to the memoir.[79] A writer for ABC News described reactions to it as an "outpouring of appreciation".[53] The book was one of 20 nominees in the Best Memoir & Autobiography category at the 2020 Goodreads Choice Awards and appeared on numerous year-end lists.[80] The Atlantic included the memoir as one of the top 15 books of 2020,[81] the Financial Times selected it as one of the top three pop music books,[82] The Times listed it as one of the top eight music books,[83] Pitchfork picked it as one of the top 15 music books,[84] NME named it one of the top 20 music books,[85] and Rolling Stone/Kirkus Reviews listed it as one of the top 21 music books.[86] The San Diego Union-Tribune named The Meaning of Mariah Carey one of the top four celebrity memoirs of the year,[87] The Guardian chose it as one of the five best celebrity memoirs,[88] the Irish Independent included it as one of the top eight celebrity memoirs and biographies,[89] and Variety named it one of the top 10 celebrity memoirs.[90] It was also highlighted by The Globe and Mail as one of the three best music memoirs/autobiographies of 2020.[91]

The book received comparisons to other works. Writing for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Adriana Ramirez considered it "an important contribution to the genre of celebrity memoir". As it explains Carey's musical creative process in addition to expected life stories, she felt it stood out from a typical memoir.[61] In the Los Angeles Times, Rich Juzwiak deemed it "an exceptional entry in the genre". He thought the "vivid anecdotes that unfold with tension and poignancy [are] not typically seen in celebrity writing".[92] British critics were disappointed it contained less gossip than Elton John's Me,[55][93] while Kirkus Reviews remarked this made it "refreshingly candid".[62]

Reviewers thought the book's effectiveness declined as it went on. According to Entertainment Weekly's Mary Sollosi, the first section is the best and everything post-1990 lost clarity because it lacked context.[59] Jon Caramanica of The New York Times considered the memoir "less revealing the later into Carey’s life it moves". He felt the exclusion of her bipolar diagnosis detracted from clarity that would have been useful during "All That Glitters" and that the latter chapters are rushed. Writing for The Guardian, Alex Macpherson thought nothing was divulged after 2005.[56]

Adaptation

In a December 2020 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Carey said she was exploring how to adapt the book into a limited series or film, and that she may direct it.[94]

Lawsuit

Carey's older sister Alison filed a lawsuit against her with the New York Supreme Court in February 2021 seeking $1.25 million for emotional distress caused by the memoir. In the chapter "Dandelion Tea", Carey writes that "when I was 12 years old, my sister drugged me with Valium, offered me a pinky nail full of cocaine, inflicted me with third-degree burns, and tried to sell me out to a pimp"—statements which Alison disputes and says were used to generate book sales.[95][96]

References

- Huff, Lauren (July 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey to release 'unfiltered' memoir in September — here are all the details". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Mariah Carey Has a New No. 1 as her Juicy Memoir Tops Bestsellers Lists". Daily News. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "8 things we learned from Mariah Carey's chat with Trevor Nelson". BBC Radio 2. October 2020. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020.

- Davis, Allison P. (August 31, 2020). "Mariah Carey on MC30, The Rarities, and her upcoming memoir". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020.

- Lovece, Frank (July 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey memoir due in September". Newsday. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020.

- Curto, Justin (July 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey finished her memoir, dahling, and it's out this September". Vulture. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020.

- Carey and Davis, pp. 5–94

- Carey and Davis, pp. 97–223

- Carey and Davis, pp. 227–269

- Carey and Davis, pp. 273–335

- Lordi, Emily (October 2, 2020). "The elusive Mariah Carey's new memoir". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020.

- Oliver, Daniel (September 25, 2020). ""I work on my emotional recovery daily": Mariah Carey reveals true vulnerability in new memoir". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020.

- Carey and Davis, pp. 114–115

- Carey and Davis, p. 103

- Carey and Davis, pp. 109–110

- Carey and Davis, p. 193

- Carey and Davis, p. 182

- Carey and Davis, pp. 166–167

- Carey and Davis, pp. 90–91

- Carey and Davis, p. 162

- Carey and Davis, p. 176

- Carey and Davis, pp. 207–208

- Carey and Davis, pp. 205–206

- Carey and Davis, p. 199

- Carey and Davis, p. 220

- Carey and Davis, pp. 231–232

- Carey and Davis, p. 276

- Carey and Davis, p. 159

- Carey and Davis, pp. 287–288

- Carey and Davis, p. 293

- Carey and Davis, p. 246

- Carey and Davis, p. 325

- Carey and Davis, p. 330

- Carey and Davis, p. 137

- Carey and Davis, p. 17

- Carey and Davis, p. 127

- Carey and Davis, p. 97

- Carey and Davis, p. 5

- Carey and Davis, p. 22

- Carey and Davis, p. 177

- Carey and Davis, p. 321

- Carey and Davis, p. 42

- Carey and Davis, p. 285

- Carey and Davis, p. 74

- Carey and Davis, p. 12

- Carey and Davis, p. 94

- Carey and Davis, p. 47

- Carey and Davis, p. 246

- Carey and Davis, p. 337

- Turchiano, Danielle (September 28, 2020). "9 most meaningful moments of Mariah Carey's memoir". Variety. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021.

- Blackmon, Michael (October 2, 2020). "Mariah Carey's new book is more revealing than you'd think". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020.

- Freeman, Hadley (October 5, 2020). "Mariah Carey: "They're calling me a diva? I think I'm going to cry!"". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020.

- Reich, Hannah (October 29, 2020). "Mariah Carey's memoir honestly traces the pop diva's journey from trauma and abuse to chart-domination". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021.

- Sheffield, Rob (October 8, 2020). "Mariah Carey's diva lit masterpiece: Knowing me, knowing you, not knowing her". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020.

- Segal, Victoria (October 4, 2020). "The Meaning of Mariah Carey by Mariah Carey, review — the singer's tell-all memoir". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021.

- Macpherson, Alex (September 29, 2020). "The Meaning of Mariah Carey review – fascinating memoir by a misunderstood star". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021.

- Lang, Cady (September 30, 2020). "The Meaning of Mariah Carey is like her top hits—pop perfection that reveals only what she wants us to know". Time. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020.

- Hyland, Véronique (December 1, 2020). "Mariah Carey is here to un-cancel Christmas". Elle. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021.

- Sollosi, Mary (September 29, 2020). "The Meaning of Mariah Carey is a compelling account of suffering and survival: Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021.

- Caramanica, Joe (October 4, 2020). "Mariah Carey, elusive no more". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- Ramirez, Adriana (October 11, 2020). "With Mariah Carey, all that glitters isn't always gold". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021.

- "The Meaning of Mariah Carey". Kirkus Reviews. September 30, 2020. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021.

- Gardner, Chris (July 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey reveals memoir title, cover and release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020.

- Legaspi, Althea (October 8, 2020). "Mariah Carey talks being biracial, finding unconditional love in Oprah interview". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020.

- Lim, Kay; McFadden, Robbyn (September 27, 2020). Barnello, Lauren (ed.). "Mariah Carey on the darkest chapters of her life". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020.

- Ritschel, Chelsea (September 29, 2020). "Mariah Carey opens up on lasting impacts of her mother's jealousy: "You have to be so careful what you say"". The Independent. New York City. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020.

- Rowley, Glenn (September 29, 2020). "Mariah Carey has a perfectly good explanation for why "Thanksgiving is cancelled", dahhlings". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020.

- Michallon, Clémence (October 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey says her young son was bullied by white supremacist person "he thought was a friend"". The Independent. New York City. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020.

- Rowley, Glenn (October 2, 2020). "Mariah Carey details "harrowing" racism she experienced as a child in "Daily Show" interview". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021.

- "Mariah Carey chats about her life, music, and new memoir". BBC Radio 2. October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020.

- "Author Live Series with Mariah Carey". Amazon. October 2, 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020.

- "The New York Times Best Sellers". The New York Times. October 18, 2020. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020.

- "Hardcover Frontlist Nonfiction". Publishers Weekly. October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021.

- "Top 10 overall". Publishers Weekly. October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020.

- "Hardcover Frontlist Nonfiction". Publishers Weekly. October 26, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021.

- "Bestsellers: Hardcover Non Fiction, October 10, 2020". The Globe and Mail. October 9, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021.

- "Toronto Star bestsellers for the week ending Oct. 7, 2020". Toronto Star. October 7, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021.

- "The Sunday Times Bestsellers". The Sunday Times. October 11, 2020. p. 24.

- "The Meaning of Mariah Carey". Book Marks. 2020. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021.

- "Best Memoir & Autobiography". Goodreads. 2020. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- "The 15 best books of 2020". The Atlantic. December 24, 2020. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021.

- "Best books of 2020: Pop music". Financial Times. November 21, 2020. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020.

- Hodgkinson, Will; Segal, Victoria (November 29, 2020). "Best music books of the year 2020". The Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021.

- "Our 15 favorite music books of 2020". Pitchfork. December 16, 2020. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021.

- Hunt, El (December 4, 2020). "The 20 best music books of 2020". NME. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020.

- Donlon, John; Browne, David; Spanos, Brittany; Sheffield, Rob; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Grow, Kory; Greene, Andy; Liebetrau, Eric (December 7, 2020). "The best music books of 2020". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021.

- Ianni, Jennifer (December 13, 2020). "A good read: The best celebrity memoirs of 2020". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020.

- Sturges, Fiona (November 28, 2020). "Best autobiography and memoirs of 2020". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021.

- Lynch, Dónal (December 6, 2020). "The best books of 2020: Our critics select their picks of the year". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021.

- Zukin, Meg; Turchiano, Danielle (November 21, 2020). "Best celebrity memoirs of 2020". Variety. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021.

- Wheeler, Brad (December 21, 2020). "Fifteen music books that struck a chord in 2020". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020.

- Juzwiak, Rich (September 23, 2020). "Review: Mariah Carey's memoir is her best performance yet". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021.

- Ditum, Sarah (October 2, 2020). "The Meaning of Mariah Carey by Mariah Carey review — keep it dramatique! The diva's life lessons". The Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020.

- Gardner, Chris (December 9, 2020). "Mariah Carey eyes adapting best-selling memoir for the screen". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021.

- Willman, Chris (February 2, 2021). "Mariah Carey sued by sister over "public humiliation" in singer's autobiography". Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021.

- Ali, Rasha (February 2, 2021). "Mariah Carey sued for $1.25 million by sister for "emotional distress" caused by memoir". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021.

Works cited

- Carey, Mariah; Davis, Michaela Angela (September 29, 2020). The Meaning of Mariah Carey. New York City: Andy Cohen Books. ISBN 978-1-2501-6468-1. LCCN 2020020198. OCLC 1157767321. OL 29879848M.

External links

- Official website

- Works by or about Mariah Carey in libraries (WorldCat catalog)