The Misfortunes of Elphin

The Misfortunes of Elphin (1829) is a short historical romance by Thomas Love Peacock, set in 6th century Wales, which recounts the adventures of the bard Taliesin, the princes Elphin ap Gwythno and Seithenyn ap Seithyn, and King Arthur. Peacock researched his story from early Welsh materials, many of them untranslated at the time; he included many loose translations from bardic poetry, as well as original poems such as "The War-Song of Dinas Vawr". He also worked into it much satire of the Tory attitudes of his own time. Elphin has been highly praised for its sustained comic irony, and by some critics is considered the finest Arthurian literary work of the Romantic period.[1][2]

Synopsis

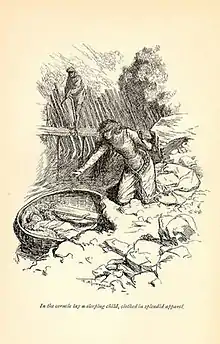

At the start of the 6th century Caredigion is ruled by king Gwythno Garanhir, and his subordinate Prince Seithenyn ap Seithyn is in charge of the embankments that protect the plain of Gwaelod in Caredigion from the sea. One of Seithenyn's officials, Teithrin ap Tathral, discovers that the embankment is in a poor state of repair, and tells Elphin, son of king Gwythno. Together they find Seithenyn, who is as usual drunk, and warn him of the dangerous state of the sea-defences, but he dismisses their fears with specious arguments. Elphin then meets Angharad, Seithenyn's beautiful daughter, and together they watch the onset of a mighty tempest, which destroys the embankment so that the sea breaks through. Seithenyn, with drunken bravado, leaps into the waves, sword in hand, but Teithrin, Elphin and Angharad make their escape to king Gwythno's castle. Gwythno is distraught at the submersion of the best part of his kingdom under Cardigan Bay. Elphin marries Angharad and settles down to earn his living from the produce of a salmon-weir he has constructed. One day he finds in this weir a coracle containing a baby, whom he names Taliesin and raises along with his own daughter, Melanghel. As Taliesin grows up he learns the precepts of Druidism and becomes a bard. Gwythno dies, and Elphin inherits the throne of the reduced and impoverished kingdom of Caredigion, but is soon abducted by Maelgon, king of Gwyneth. Maelgon's son, Rhun, visits Elphin's home and seduces a woman whom he believes to be Angharad, but who is actually her servant. Taliesin sets out to free Elphin at the prompting of his foster-sister, Melanghel, with whom he is in love. At Maelgon's court he announces himself as a bard of Elphin, vindicates Angharad's honour, and enters into a poetic contest with Maelgon's bards, in the course of which he warns him of various impending dooms, including an attack by King Arthur and death by plague. Taliesin returns to Caredigion. Rhun follows him, wanting to make a second attempt on Angharad, but he is lured into a cave and there imprisoned when a boulder is released to seal up the entrance. Taliesin sets out to find King Arthur in Caer Lleon. On his way there he stops at Dinas Vawr, a fortress just captured by king Melvas, whose men are celebrating their victory in wine and song; among them he is astounded to find Angharad's father, Seithenyn ap Seithyn, who it turns out survived the flooding of Gwaelod so many years before. Taliesin reaches Caer Lleon, admires its splendours, then gets audience of King Arthur, who is keeping Christmas merrily, even though his wife Gwenyvar has been abducted by person or persons unknown. He tells the king a secret he has learned from Seithenyn, that Gwenyvar is being held by Melvas; then he moves on to Avallon, where Gwenyvar is being kept captive, in the hope of negotiating her peaceful release. There he meets Seithenyn again, together with the abbot of Avallon, both of whom agree to help him. Together these three convince Melvas that he has more to gain by voluntarily releasing Gwenyvar to Arthur than by facing Arthur's wrath. Back in Caer Lleon Taliesin takes part in another bardic contest. Llywarch sings his "The Brilliancies of Winter", Merlin his "Apple Trees" and Aneirin his "The Massacre of the Britons", but Taliesin's contribution, a portion of the Hanes Taliesin, is declared the finest. Seithenyn and the abbot then make their entrance, bringing Gwenyvar with them, and having restored her to Arthur they tell him that Taliesin was instrumental in securing her release. The grateful king grants Taliesin a boon, and Taliesin begs that Arthur will command Maelgon to release Elphin. Maelgon himself makes his appearance at this point and unwillingly submits to Arthur's will. Arthur sends an emissary to fetch Elphin, Rhun, and all other concerned parties, including Melanghel. The story ends with Taliesin's marriage to Melanghel, and election as Chief of the Bards of Britain.

Composition

Peacock's passionate interest in Welsh culture began many years before he wrote anything on the subject. In 1810–1811 he made a walking tour of Wales, returning three more times in the next few years, and he probably made use of his observations of the country in The Misfortunes of Elphin.[3] He had a gift for languages, and is said to have taken his first steps in learning Welsh at this time.[4][5] In 1820 he married a Welsh lady, Jane Gryffydh, who, it is supposed, either tutored him in the language or else acted as his translator. Certainly Elphin displays a knowledge of early Welsh materials, some of which were then unavailable in English translation.[6][3] It is a reasonable surmise that his wife served as the model for Angharad and Melanghel. In 1822 he moved to a house in the village of Lower Halliford, Surrey, and it was here that Elphin was written.[7] He chose to include 14 poems in his story, most of them being loose translations or adaptations of bardic poems by, among others, Taliesin, Myrddin and Llywarch Hen, though some, such as "The War-Song of Dinas Vawr", were original compositions. Elphin was published seven years after his previous book, Maid Marian (1822). It is possible that it had a long gestation because of the many other demands on Peacock's time, such as a full-time job at East India House and the work involved in serving as his friend Shelley's executor, and because his research was so assiduous, but it has also been argued that he did not begin to write it until late in 1827.[8][9] The Misfortunes of Elphin was eventually published in March 1829.[6]

Sources

Peacock's use of traditional and medieval Welsh-language sources was somewhat unusual in his time, when, outside Wales itself, they were generally thought unsuitable for use in works of literature. Though generally remaining true to their spirit, he reduces the role of the supernatural in these stories. The narrative structure of Elphin is based on three ancient tales: the inundation of Gwythno's kingdom through the negligence of Seithenyn, the birth and prophecies of Taliesin, and the abduction of Gwenyvar by Melvas.[10] The first of these tales is told in a poem in the Black Book of Carmarthen, but was also available to Peacock in two English language sources, Samuel Rush Meyrick's History and Antiquities of Cardigan (1806) and T. J. Llewelyn Prichard's poem The Land Beneath the Sea (1824). The Taliesin story is told in the Hanes Taliesin. This was not available in full in the 1820s, either in English or in the original Welsh, but summaries and fragments of it were available in Edward Davies's The Mythology and Rites of the Druids (1809) and elsewhere.[11][12] Peacock's version of the story of Arthur, Gwenyvar and Melvas derives ultimately from the 12th-century Latin Vita Gildae by Caradoc of Llancarfan, probably via Joseph Ritson's Life of King Arthur (1825).[13][14] The poems scattered through Elphin are for the most part translated or imitated from originals published in Owen Jones's Myvyrian Archaiology (1801–1807).[3] The Welsh triads Peacock quoted were available to him in translation in a journal called The Cambro-Briton (1819–1822), one of the major sources of his novella.[15][16][17] The extended description of Caerleon owes much to Richard Colt Hoare's 1806 translation of Gerald of Wales's Itinerarium Cambriae and Descriptio Cambriae, but other topographical descriptions draw on Thomas Evans's Cambrian Itinerary and, probably, on Peacock's own memories of his various Welsh holidays.[12][18]

Satire and humour

Quite apart from being a historical romance The Misfortunes of Elphin is also a sustained satirical attack on contemporary Tory attitudes. Gwythno's dam stands for the British constitution, Seithenyn's speech disclaiming any need to repair it echoes various of George Canning's speeches rejecting constitutional reform, and the inundation represents the pressure for reform, or alternatively the French Revolution.[19][20][4][21] Peacock also makes numerous ironic comments about the blessings of progress, and in his portrayal of the "plump, succulent" abbey of Avallon he attacks the over-comfortable clergy of the Church of England.[20] Other targets of his satire include industrialization, the doctrine of utilitarianism, realpolitik, pollution, paper money, false literary taste and the Poet Laureateship.[22][23][24] These attacks on the follies of his own times do not, however, lead Peacock to idealize his medieval characters by contrast. Arthur is less than distraught at his wife's absence, Gwenyvar is no better than she ought to be, Merlin is a secret pagan whose supposed magic is merely natural philosophy, and such human frailties are seen as driving history.[25] Human nature, for Peacock, was imperfect in very similar ways in all periods of history.[26]

The appeal of The Misfortunes of Elphin for the modern reader depends largely its unusual blending of an Olympian irony with simple good humour.[27] The result has been described as "comic genius of the highest order".[28] J. B. Priestley analysed the stylistic devices which help to produce this effect:

A crisp rhythm, a perfectly grave manner, a slight heightening of language, a curious little "smack" in each sentence, suggesting a faint and curiously droll over-emphasis in pronunciation if we think of the prose being spoken...the very restraint of the voice, its even tones, only serve to heighten the effect of the bland sarcasm and the lurking drollery that find their way into almost every sentence.[29]

The comic and ironic invention of the novel is seen at its finest in the character of Seithenyn, "one of the immortal drunkards in the literature of the world", as David Garnett described him.[27][30] He is "a Welsh Silenus, a tutelary spirit of an amiable and approachable type",[31] whose conversational style, with its alcoholically twisted logic, has led to his being repeatedly compared to Falstaff.[28][23] He is perhaps Peacock's greatest character.[32][33][34] Priestley devoted a whole chapter of his English Comic Characters (1925) to Seithenyn,[35] and criticism of Elphin has mostly focused on him, though Felix Felton argued that he is only one of a trio of characters on whom the work really rests, the others being Taliesin and Elphin.[36]

Reception

The reviews of The Misfortune of Elphin were almost wholly appreciative. The Edinburgh Literary Journal, reviewing another work, may have referred to Elphin as "a very unintelligible book",[37] but the Literary Gazette called it "one of the most amusing volumes which we have perused for a long, long time".[38] The Cambrian Quarterly Magazine thought it "the most entertaining book, if not the best, that has yet been published on the ancient customs and traditions of Wales".[39] The Radical Westminster Review was, predictably, more amused by the ridicule of Tory sentiments than by Peacock's sideswipes at Benthamism and political economy.[40] A brief but laudatory notice in the New Monthly Magazine found the satire to be almost as effective as Swift's.[41] The Athenaeum, though it found a falling-off from Peacock's previous novels, could nevertheless recommend it to "every person who can relish wit, humour, and exquisite descriptions, as a work of a very superior class to the popular novels of the day".[42] In spite of this critical praise sales of The Misfortunes of Elphin were disappointing. Copies of the first edition were still being remaindered 40 years later, and though Peacock's other novels were all reissued in 1837 and 1856, Elphin was not.[2][43]

In the 20th century critics were agreed in preferring The Misfortunes of Elphin to Peacock's other historical romance, Maid Marian, and many considered it the finest of all his novels.[44][34] Among these were Robert Nye, who wrote that it shows "Peacock at the height of his powers...a demigod on a spree",[45] and A. Martin Freeman, who thought it "perhaps the completest statement of his point of view", showing Peacock "at the summit of his achievement...absolutely at his ease, a master of his subject and of English prose".[46] Bryan Burns thought that "as a piece of story-telling which mingles celebration with attack, a subdued but trenchant treatment of themes of authority and individual freedom and an admirable achievement of style, it is hard to equal in the rest of Peacock's oeuvre."[47] Marilyn Butler considered it "his very best strictly political book – and that is to place it high among political satires in English".[48] J. B. Priestley declared that "to read it once is inevitably to read it again".[49] On the other hand, Carl Dawson felt that the contemporary references, though they made the book relevant to Peacock's contemporaries, dated the book for later readers: "Elphin is a type of novel that has to be rewritten for each generation. Its equivalent in our own day is perhaps T. H. White's The Once and Future King."[50]

The Misfortunes of Elphin is sometimes said to be one of the few English works of genius to have been inspired by the 19th-century Celtic Revival.[35] Peacock studied his early Welsh sources with respect for their vigour, sense of wonder, hyperbole and inventiveness with language, and is said by favourable critics to have evoked their spirit vividly while tempering them with "Attic lucidity and grace".[51][28] On the other hand unfavourable critics have disparaged his choice of Welsh rather than English or French sources for his Arthurian story. James Merriman, for example, thought it a "minor work" precisely because of its use of "distinctly inferior materials".[52]

There is not total agreement between critics as to the narrative skill displayed in Elphin. Bryan Burns wrote of "the insouciance and diversity of its story-telling...there is real command in the spacing and contrasting of episodes, the organizing of space and the economy and poise of individual scenes",[53] while Marilyn Butler judged that of all Peacock's books Elphin has the strongest plot,[54] but Priestley on the contrary believed that "he has no sense of narration, of the steady march forward of events, of the way in which action can be ordered to produce the best effect". One of his objections was that "the action is continually held up by the songs, of which there are far too many".[49] The critic Olwen W. Campbell agreed that these "long and tedious adaptations of bardic songs" interrupted the story,[55] but Bryan Burns, while objecting to the "mannerly loftiness" Peacock shared with other minor poets of his period, thought these songs served a useful purpose in the story as outlets for romantic sentiment and local colour.[56] There is wide agreement that the original poems in Elphin are superior to the translations and imitations, and that "The War-Song of Dinas Vawr", later taken up and adapted by T. H. White in The Once and Future King, is the best of them.[57][58][59][27][39]

Footnotes

- Gossedge 2006, p. 157.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 60.

- Simpson 1990, p. 103.

- Gossedge & Knight 2012, p. 111.

- Garnett 1948, p. 549.

- Joukovsky 2004.

- Burns 1985, p. 139.

- Garnett 1948, pp. 547, 549–551.

- Butler 1979, p. 157.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, pp. 54–55.

- Simpson 1990, pp. 103–104.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 55.

- Whitaker 1996, p. 353.

- Simpson 1990, p. 104.

- Simpson 1990, p. 105.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, pp. 55–56.

- Garnett 1948, p. 550.

- Simpson 1990, pp. 103–105.

- Drabble, Margaret, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 678. ISBN 0198614535. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Whitaker 1996, pp. 353–354.

- Freeman 1911, p. 286.

- Simpson 1990, pp. 43, 46.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 58.

- Draper, John W. (December 1918). "The Social Satires of Thomas Love Peacock". Modern Language Notes. 33 (8): 462. doi:10.2307/2915800. JSTOR 2915800. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 57.

- Mulvihill 1987, p. 105.

- Garnett 1948, p. 551.

- Herford 1899, p. 133.

- Priestley 1927, p. 192.

- Whitaker 1996, p. 354.

- Burns 1985, p. 156.

- Priestley 1927, p. 185.

- Dawson 1970, p. 247.

- Campbell 1953, p. 63.

- Stephens 1986, p. 400.

- Felton, Felix (1973). Thomas Love Peacock. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 202. ISBN 0049280260.

- "[Review of The Westminster Review, No. XX, and The Monthly Magazine, No. XL]". The Edinburgh Literary Journal; Or, Weekly Register of Criticism and Belles Lettres (23): 315. 18 April 1829. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Burns 1985, p. 138.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 56.

- "[Review of The Misfortunes of Elphin]". The Westminster Review. 10 (20): 428–435. April 1829. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Critical Notices". The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal. 27: 142. 1 April 1829. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "The Misfortunes of Elphin". The Athenaeum and Literary Chronicle (80): 276–278. 6 May 1829. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Campbell 1953, p. 68.

- Mulvihill 1987, p. 101.

- Nye, Robert (11 April 1970). "Unclubbable Peacock". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Freeman 1911, pp. 290, 299.

- Burns 1985, p. 164.

- Butler 1979, p. 182.

- Priestley 1927, p. 179.

- Dawson 1970, p. 253.

- Taylor & Brewer 1983, p. 54.

- Gossedge 2006, p. 158.

- Burns 1985, p. 152.

- Butler 1979, p. 155.

- Campbell 1953, p. 64.

- Burns 1985, pp. 144–145.

- Madden, Lionel (1967). Thomas Love Peacock. London: Evans Brothers. p. 65. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Freeman 1911, p. 293.

- Dawson 1970, p. 249.

References

- Burns, Bryan (1985). The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock. Totowa: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 038920532X. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butler, Marilyn (1979). Peacock Displayed: A Satirist in His Context. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710002938.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Olwen W. (1953). Thomas Love Peacock. London: Arthur Barker.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawson, Carl (1970) [1968]. His Fine Wit: A Study of Thomas Love Peacock. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeman, A. Martin (1911). Thomas Love Peacock: A Critical Study. New York: M. Kennerley. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garnett, David, ed. (1948). The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock. London: Rupert Hart-Davis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gossedge, Robert (2006). "Thomas Love Peacock's The Misfortunes of Elphin and the Romantic Arthur". Arthurian Literature. 23: 157–176. ISBN 9781843840978. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gossedge, Rob; Knight, Stephen (2012) [2009]. "The Arthur of the Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries". In Archibald, Elizabeth; Putter, Ad (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–119. ISBN 9780521860598. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herford, C. H. (1899) [1897]. The Age of Wordsworth. London: George Bell. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joukovsky, Nicholas A. (23 September 2004). "Peacock, Thomas Love". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21681.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mulvihill, James (1987). Thomas Love Peacock. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 9780805769579. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Priestley, J. B. (1927). Thomas Love Peacock. London: Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Roger (1990). Camelot Regained: The Arthurian Revival and Tennyson, 1800–1849. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0859913007. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephens, Meic, ed. (1986). The Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192115863. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Beverly; Brewer, Elisabeth (1983). The Return of King Arthur: British and American Arthurian Literature Since 1800. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 9780859911368. Retrieved 5 March 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitaker, Muriel A. (1996). "Peacock, Thomas Love". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.). The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 353–354. ISBN 9781568654324.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Full text at the Camelot Project

- Full text at the Internet Archive

- Full text at Google Books

- Full text at thomaslovepeacock.net