The Pitchfork Disney

The Pitchfork Disney is a 1991 stage play by Philip Ridley.[1] It was Ridley's first professional work for the stage, having also produced work as a visual artist, novelist, filmmaker, and scriptwriter for film and radio.[2] The play premiered at the Bush Theatre in London, UK in 1991 and was directed by Matthew Lloyd, who went on to direct the majority of Ridley's early stage plays.[3][4]

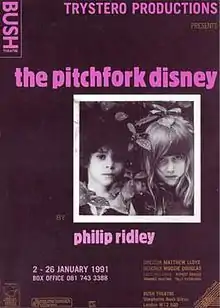

| The Pitchfork Disney | |

|---|---|

Poster advertising the original 1991 production | |

| Written by | Philip Ridley |

| Characters | Presley Stray (Male, aged 28) Haley Stray (Female, aged 28) Cosmo Disney (Male, aged 18) Pitchfork Cavalier (Male) |

| Date premiered | 2 January 1991 |

| Place premiered | Bush Theatre, London |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | In-yer-face theatre |

| Setting | "A dimly lit room in the East End of London" |

The play was a controversial hit and is generally regarded as kick-starting a new, confrontational "In-yer-face" style and sensibility of drama which emerged in British theatre during the 1990s.[5][6][7]

The play is the first entry in Ridley's unofficially titled "East End Gothic Trilogy", being followed by The Fastest Clock in the Universe and Ghost from a Perfect Place.[8][9]

In 2015 the published script was reissued as part of the Methuen Drama Modern Classics series, recognising the play's impact on modern British theatre.[10]

Synopsis

The play opens with the characters of Presley and Haley, two adults living alone in the East End of London. They lead a childish fantasy existence, living mainly off chocolate. Their parents died a decade before, although their exact fate is not described.

They tell each other stories and discuss their dreams and fears.

From their window, they see two men, one of whom is apparently sick. Agitated, Haley sucks on a drugged dummy and goes to sleep. Despite their fear of outsiders, Presley brings the sick man in, who promptly vomits on the floor. The man introduces himself as Cosmo Disney, and explains that he and his partner are showmen. His sickness is caused by the fact that his particular talent consists of eating insects and small animals. Cosmo emotionally manipulates Presley who tells Cosmo about a recurring dream he has, involving a serial killer named 'The Pitchfork Disney'.

Almost immediately after Presley finishes his story, Cosmo's partner arrives. He is a huge, masked and apparently mute figure named Pitchfork Cavalier. His act is simply taking his mask off to reveal his hideously deformed face. He sings a wordless song, dances with the unconscious Haley and eats some chocolate. Cosmo convinces Presley to accompany Pitchfork to the shops, promising friendship. As soon as they leave, Cosmo performs a sexual assault on Haley by inserting one of his fingers soaked in medicine into her mouth. Presley unexpectedly returns and realises Cosmo's true motives, and breaks his finger which he used to assault Haley. Cosmo flees. Pitchfork briefly returns, terrifies Presley and then leaves. Haley awakes, and the two express their fear.

Themes and interpretation

The play is a dreamlike piece with surreal elements. It primarily deals with fear, particularly childhood fears. Dreams and stories are also explored, and indeed, the entire play can be interpreted as a dream in itself.

Another recurring theme is that of snakes, being described by Presley in two monologues. In the first he describes killing one in a frying pan and in the second he recounts seeing one kill a mouse in the reptile house of a zoo and then later coming home and watching a television programme about a Christian cult who worship snakes. Cosmo himself can be interpreted as being a manifestation of a snake as he eats insects and small animals, claims to have been born hatching from an egg and that he got new skin from unzipping and throwing away the skin he had from being a baby. Presley in one of the monologues describes seeing a snake shed its skin to reveal bright red skin underneath. This description seems to echo Cosmo, who enters the play wearing a long black overcoat which he takes off to reveal the red-sequinned-jacket he is wearing underneath.

Concerning interpretations of The Pitchfork Disney Ridley mentioned in 2016 that “Every time it’s revived it means something different. There’s a production of it on in Canada at the moment which in the present climate is being seen as a play about terrorism – about the fear of the outside coming in and the fear of change. A few years ago it was about the fear of sex, intimacy, of being touched... [my plays are] like tuning forks, they vibrate with whatever’s going on in the atmosphere at the time.”[11]

Development

Ridley began writing the play while still an art student at St Martin's School of Art. While there he created a number of performance art pieces consisting of long fast-paced monologues detailing dream sequences and characters with shifting identities, which usually Ridley would perform in art galleries. From writing these some of Ridley's friends, who were leaving art school to instead pursue acting, suggested that his monologues would make a good basis for a stage play.[12] Ridley began writing The Pitchfork Disney based on two of his monologues that were companion pieces, one centring on a character who was afraid of everything and one who was afraid of nothing, with the play forming from the idea of what would happen if these two characters met.[13]

Ridley in part got the inspiration for the character of Cosmo from when, at the age of 18, he witnessed in a pub a man wearing a red sequined jacket proceed to eat a variety of different insects onstage for entertainment.[14]

Reception and legacy

Initial reception

The play was considered shocking for the time it was produced, with reportedly some walkouts throughout the show's run, along with rumours of audience members fainting. One verified account of an audience member fainting happened when Ridley was in the audience which lead to discussions backstage about if there should be a nurse present in the theatre for each performance.[9]

Generally the reviews from critics of the play during its initial run praised the production for its acting and direction, but were critical towards Ridley's script.[15]

A number of critics felt that the play was purposely trying to be repulsive. Critic Maureen Paton described the play as “ludicrously bad” and a “repugnant tiresome story… Mr. Ridley’s Grimm obsessions are in the worst possible taste”, concluding that “This pointless wallow makes Marat-Sade seem like Pontins Holiday Camp.”[16] Melanie McDonagh for The Evening Standard wrote that “Philip Ridley, is simply the Fat Boy from the Pickwick Papers, who sneaks up on old ladies and hisses: "I want to make your flesh creep".”[17] For The Jewish Chronicle, David Nathan commented “To the Theatre of the Absurd, the Theatre of Comedy and the Operating Theatre you can now add the Theatre of Yuk” and argued that although “The arousal of disgust is as legitimate a dramatic objective as the arousal of any other strong emotion, but as an end in itself it seems pointless.”[18]

Some critics also felt that the play was derivative of other works (particular the early plays of Harold Pinter and the work of Jean Cocteau) with City Limits critic Lyn Gardner writing that the script was “derivative of some (more famous) playwrights' worst plays”.[19] In comparing the enigmatic quality of the play to Pinter's writing, Maureen Paton wrote "Where Pinter's ironic technique like a two-way mirror can give an intellectual patina to a mystery wrapped in an enigma, Ridley seems luridly self-indulgent… Ridley drops various ominous hints that are never resolved, leaving the audience to wallow in the mire of pointless speculation.”[20]

Likewise, another reoccurring criticism was that the script was contrived and lacked specific explanations for its content. Lyn Gardner wrote that the play “has no discernible internal logic, spewing imagery meaninglessly from nowhere… with long meandering monologues which… go nowhere and appear to have no dramatic impetus… [It has an] air of contrived weirdness when what is desperately needed is a sense of reality and some concrete explanations.”[19] Benedict Nightingale for The Times wrote that “the play's obscurities becom[e] irksome” but stated that “There is no obligation on a dramatist to explain his characters' behaviour. Perhaps it is enough for Ridley to cram his play with images of childhood guilt, confusion, self-hatred and dread, leaving the audience… to the dramatic Rorschach blot that emerges… Maybe Ridley will be more specific in his next play.”[21]

Despite these criticisms the script did receive praise from some critics. An overwhelmingly positive review came from Catherine Wearing who wrote in What's On “This is a world premiere you must rush to see… [Ridley] presents a world that is boldly dramatic, dead contemporary and sickeningly terrifying. At last, some new work for the theatre that has vision and bravery in its telling… There's a sinister and original mind at work here with lots to say… Dark powerful and choc a-bloc with shock tactics this must be a must for anyone who wants dynamic, contemporary theatre.”[22]

Reacting to the reviews, Ian Herbert in Theatre Record wrote that there was “a most encouraging set of disagreements” amongst critics regarding The Pitchfork Disney. He then went on to defend the play citing it as “a very important debut”, compared Ridley's writing favourably to Harold Pinter's and added that Ridley was a writer to watch out for: “he has a little to learn yet about dramatic structure and all the boring rules, but he can already create astonishingly original characters and give them lines that hold an audience spellbound.”[23]

By the end of its original run the play had acquired something of a cult following, with a group of actors reportedly seeing the production several times and attending the production's final performance wearing T-shirts with lines from the play printed on them in big bold lettering. It was so successful that the Bush Theatre for the first time in its history had to schedule an extra matinee performance to meet audience demand.[9]

For his performance as Presley, Rupert Graves subsequently won the Charrington Fringe Award for Best Actor.[24]

Legacy

Years after its premiere the play gained in reputation, achieving recognition as a major work and highly influential in the development of in-yer-face theatre, which dominated new writing in British Theatre during much of the 1990s.

Bush Theatre artistic director Dominic Dromgoole wrote in 2000 that the play "took the expectations of a normal evening in the theatre, rolled them around a little, jollied them along, tickled their tummy, and then savagely, fucked them up the arse… Performed right at the beginning of 1990, this was one of the first plays to signal a new direction for new writing. No politics, no naturalism, no journalism, no issues. In its place, character, imagination, wit, sexuality, skin and the soul."[25]

Critic and leading expert on In-yer-face theatre, Aleks Sierz, has often cited the play as a pioneering work. In his introduction to the Methuen Classics edition of the play-text, Sierz wrote “The Pitchfork Disney is not only a key play of the 90s; it is the key play of that decade... Its legend grew and grew until it became the pivotal influence on the generation of playwrights that followed. It is a foundation text; it separates then from now.”[9]

Despite the play being cited as a key work in instigating the in-yer-face theatre style and sensibility, Ridley has spoken about how he feels that The Pitchfork Disney (along with his other plays in the so-called “East End Gothic Trilogy”) were produced before in-yer-face theatre happened: "I had done my first three plays… by 1994 and that’s the year that most people say the ‘in your face’ thing started. All those seeds were laid before that, but it didn't feel that I was doing that and no one said I was doing that until many years after the event."[7] "When in-yer-face was happening I was writing plays for young people."[26]

Significant plays that critics believe have been influenced by or bear homage to the play include:

- Penetrator by Anthony Neilson (1993)[27]

- Blasted by Sarah Kane (1995)[27][9]

- Mojo by Jez Butterworth (1995)[27][9]

- Shopping and Fucking by Mark Ravenhill (1996)[27][9]

- Been so long by Ché Walker (1998)[28]

- Dirty Butterfly by debbie tucker green (2003)[9]

- Debris by Dennis Kelly (2003)[27][9]

- The Pillowman by Martin McDonagh (2003)[27][9]

- Three Birds by Janice Okoh (2013)[29]

Monologues from the play have also become popular audition pieces, most notably Presley's speech about killing a snake in a frying pan[30] and Hayley's speech about being chased into a church by savage dogs.[31]

Notable productions

World Premiere (London, 1991)

2 January 1991 at The Bush Theatre, London.

Directed by Matthew Lloyd.

- Presly Stray - Rupert Graves

- Haley Stray - Tilly Vosburgh

- Cosmo Disney - Dominic Keating

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Stuart Raynor

Glasgow Revival (1993)[32]

Citizens' Theatre, Glasgow.

Directed by Malcolm Sutherland.

- Presly Stray - Michael Matus

- Haley Stray - Helen Baxendale

- Cosmo Disney - Matthew Wait

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Ché Walker

American Premiere (Washington D.C., 1995)[33]

5 February 1995 at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Washington D.C.

Directed by Rob Bundy.

- Presly Stray - Wallace Acton

- Haley Stray - Mary Teresa Fortuna

- Cosmo Disney - Michael Russotto

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Bill Delaney

Winner of ‘Outstanding resident play’ and ‘Outstanding lead actor, resident play’ for Wallace Acton at the Helen Hayes Awards,[34] with nominations also for ‘Outstanding Supporting actress, resident play’ for Mary Teresa Fortuna, ‘Outstanding Director, resident play’ for Rob Bundy, ‘Outstanding Set Design, resident play or musical’ for James Kronzer and ‘Outstanding Sound Design, resident play or musical’ for Daniel Schrader.[35]

January 16 1997[38] at the Octagon Theatre, Bolton.

Directed by Lawrence Till.

- Presley - Matthew Vaughan

- Hayley - Andrea Ellis

- Cosmo - Gideon Turner

- Pitchfork – David Hollett

New York Premiere (1999)[39]

8 April 1999 at Blue Light Theater Company, New York.

Directed by Rob Bundy.

- Presly Stray - Alex Drape

- Haley Stray - Lynn Hawley

- Cosmo Disney - Alex Kilgore

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Brandt Johnson

London Revival 2012 (21st Anniversary Production)[40]

25 January - 17 March 2012 at The Arcola Theatre, London.

Directed by Edward Dick.

- Presly Stray - Chris New

- Haley Stray - Mariah Gale

- Cosmo Disney - Nathan Stewart-Jarrett

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Steve Guadino

London Revival 2017[41]

27 January - 18 March 2017 at Shoreditch Town Hall, London.

Directed by Jamie Lloyd.

- Presly Stray - George Blagden

- Haley Stray - Hayley Squires

- Cosmo Disney - Tom Rhys Harries

- Pitchfork Cavalier - Seun Shotes

Winner of the 2018 Off West End Awards for 'Best Supporting Male in a Play', awarded to Tom Rhys Harries.[42] Also nominated were George Blagden for ‘Best Male in a Play’ (longlisted) and Jamie Lloyd for ‘Best Director’ (longlisted).[43]

Further reading

- Herbert, Ian, ed. (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. pp. 11–14. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Urban, Ken (2007). Ghosts from an Imperfect Place: Philip Ridley's Nostalgia.

- Rebellato, Dan (17 October 2011). "Chapter 22: Philip Ridley by Dan Rebellato". In Middeke, Martin; Paul Schnierer, Peter; Sierz, Aleks (eds.). The Methuen Drama Guide to Contemporary British Playwrights. London, Great Britain: Methuen Drama. pp. 427–430. ISBN 9781408122785.

- Sierz, Aleks (24 May 2012). Modern British Playwriting: The 1990s: Voices, Documents, New Interpretations. Great Britain: Methuen Drama. pp. 91–98. ISBN 9781408181331.

References

- Ridley, Philip (1991). The Pitchfork Disney. Methuen Drama. ISBN 9781472510471.

- Sierz, Aleks (24 May 2012). Modern British Playwriting: The 1990s: Voices, Documents, New Interpretations. Great Britain: Methuen Drama. p. 89. ISBN 9781408181331.

- CV of director Matthew Lloyd

- Review by Ian Shuttleworth of the original production of Ridley's 2000 play Vincent River directed by Matthew Lloyd

- Gardner, Lyn (6 February 2012). "The Pitchfork Disney – review". The Guardian. London.

- Audio recording of lecture given by Aleks Sierz entitled 'Blasted and After: New Writing in British Theatre Today' at a meeting of the Society for Theatre Research, at the Art Workers Guild, London on 16 February 2010

- "Philip Ridley On ... Revisiting The Pitchfork Disney". WhatsOnStage.com. London. 30 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Rebellato, Dan (17 October 2011). "Chapter 22: Philip Ridley by Dan Rebellato". In Middeke, Martin; Paul Schnierer, Peter; Sierz, Aleks (eds.). The Methuen Drama Guide to Contemporary British Playwrights. London, Great Britain: Methuen Drama. p. 426. ISBN 9781408122785.

- Sierz, Aleks (21 October 2015). Introduction. The Pitchfork Disney. By Ridley, Philip. Modern Classics (Reissue ed.). Great Britain: Methuen Drama. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-1-4725-1400-4.

- Modern Classics Edition of The Pitchfork Disney listed on Bloomsbury Publishing's Website

- Faber, Tom (24 May 2016). "Theatre Teaches You To Be Human: An Interview with Philip Ridley". londoncalling.com. London Calling Arts Ltd. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Ridley, Philip (15 October 2015). "Mercury Fur - Philip Ridley Talkback" (Interview: Audio). Interviewed by Paul Smith. Hull. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Rebellato, Dan (17 October 2011). "Chapter 22: Philip Ridley by Dan Rebellato". In Middeke, Martin; Paul Schnierer, Peter; Sierz, Aleks (eds.). The Methuen Drama Guide to Contemporary British Playwrights. London, Great Britain: Methuen Drama. p. 425. ISBN 9781408122785.

- Ridley, Philip (2012). "Introduction: Chapter LIII". Philip Ridley Plays 1: Pitchfork Disney; Fastest Clock in the Universe; Ghost from a Perfect Place. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. pp. lvii–lviii. ISBN 978-1-4081-4231-8.

- "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. January 1991. pp. 11–14. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Paton, Maureen (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 11. ISSN 0261-5282.

- McDonagh, Melanie (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 11. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Nathan, David (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 12. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Gardner, Lyn (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 11. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Paton Maguire, Maureen (17 January 1991). "Bush: The Pitchfork Disney". The Stage. The Stage Media Company Limited. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Nightingale, Benedict (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. pp. 12–13. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Wearing, Catherine (January 1991). "The Pitchfork Disney". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 14. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Herbert, Ian (January 1991). "Prompt Corner". Theatre Record. Vol. XI no. 1. England: Ian Herbert. p. 3. ISSN 0261-5282.

- Photograph of newspaper clipping

- Dromgoole, Dominic (2000). The Full Room: An A-Z of Contemporary Playwriting (1st ed.). London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 0413772306.

- Ince, Robin; Long, Josie (12 January 2017). "Book Shambles - Season 4, Episode 13 - Philip Ridley". SoundCloud (Podcast). Event occurs at 40.30. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Rebellato, Dan (17 October 2011). "Chapter 22: Philip Ridley by Dan Rebellato". In Middeke, Martin; Paul Schnierer, Peter; Sierz, Aleks (eds.). The Methuen Drama Guide to Contemporary British Playwrights. London, Great Britain: Methuen Drama. p. 441. ISBN 9781408122785.

- Sierz, Aleks (5 March 2001). In-Yer-Face Theatre: British Drama Today. Great Britain: Faber and Faber Limited. p. 196. ISBN 0-571-20049-4.

- Wilkinson, Devawn (25 March 2013). "Review: Three Birds". A Younger Theatre. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- List by Karen Kohlhaas of 'Overdone Men's Monologues' at auditions

- Website with options for female monologues as audition speeches

- Benjamin, Eva (29 April 1993). "Glasgow: The Pitchfork Disney". The Stage. The Stage Media Company Limited. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Brantley, Ben (8 February 1995). "THEATER REVIEW: THE PITCHFORK DISNEY; HEDDA GABLER; To Stay Home or Not: Varieties of Fear and Peril". The New York Times. New York.

- Viagas, Robert (7 May 1996). "DC Helen Hayes Awards Winners Announced". Playbill. New York.

- Lundy, Katia (12 April 1996). "Helen Hayes Award Nominees". Playbill. New York.

- Wainwright, Jeffrey (22 January 1997). "Review: THEATRE The Pitchfork Disney Bolton Octagon". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Anglesey, Natalie (30 January 1997). "Bolton: The Pitchfork Disney". The Stage. The Stage Media Company Limited. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Neil's naughty animals visit the Octagon at Christmas". The Bolton News. Newsquest (North West) Ltd. 6 August 1996. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- McGrath, Sean; Jones, Kenneth (7 April 1999). "After Delay, Blue Light Disney to Open at NY's HERE April 8". Playbill. PLAYBILL INC. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Webpage of 2012 revival

- Archive page of The Pitchfork Disney at Shoreditch Town Hall

- "Offies 2018: Full list of Off West End Award winners". LondonTheatre.co.uk. LondonTheatre.co.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "OFFIE Panel Nominations for 2017 (Longlist)". OffWestEnd.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

External links

- Philip Ridley interviewed by Aleks Sierz for TheatreVoice about The Pitchfork Disney and its 2012 revival

- Philip Ridley interviewed by Chelsey Burdon for A Younger Theatre about The Pitchfork Disney and its 2012 revival

- Philip Ridley interviewed by Theo Bosanquet for WhatsOnStage about The Pitchfork Disney and its 2012 revival