The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (German: Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft) is a 1962 book by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas. It was translated into English in 1989 by Thomas Burger and Frederick Lawrence. An important contribution to modern understanding of democracy, it is notable for "transforming media studies into a hard-headed discipline."[1]

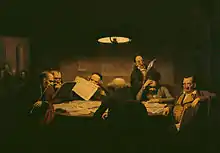

.jpg.webp) Cover of the German edition | |

| Author | Jürgen Habermas |

|---|---|

| Original title | Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft |

| Translators | Thomas Burger Frederick Lawrence |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | The public sphere |

| Published | 1962 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 978-0262581080 |

The public sphere

The notion of the "public sphere" began evolving during the Renaissance in Western Europe. Brought on partially by merchants' need for accurate information about distant markets as well as by the growth of democracy and individual liberty and popular sovereignty, the public sphere was a place between private individuals and government authorities in which people could meet and have critical debates about public matters. Such discussions served as a counterweight to political authority and happened physically in face-to-face meetings in coffee houses and cafes and public squares as well as in the media in letters, books, drama, and art.[2] Habermas saw a vibrant public sphere as a positive force keeping authorities within bounds lest their rulings be ridiculed. According to the journalist David Randall, "In Habermasian theory, the bourgeois public sphere was preceded by a literary public sphere whose favored genres revealed the interiority of the self and emphasized an audience-oriented subjectivity."[2]

Habermas' thesis

| Part of a series on the |

| Frankfurt School |

|---|

|

|

The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere was Habermas's first major work. It also satisfied the rigorous requirements for a professorship in Germany; in this system, independent scholarly research, usually resulting in a published book, must be submitted, and defended before an academic committee; this process is known as Habilitationsschrift or habilitation. The work was overseen by the political scientist Wolfgang Abendroth, to whom Habermas dedicated it. Habermas describes the development of a bourgeois public sphere in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as well as its subsequent decline.

The first transition occurred in England, France, the United States, and Germany over the course of 150 years or so from the late seventeenth century. England led the way in the early eighteenth century, with Germany following in the late eighteenth century. Habermas tries to explain the growth and decline of the public sphere by relating political, social, cultural and philosophical developments to each other in a multi-disciplinary approach. Initially, there were monarchical and feudal societies which made no distinction between state and society or between public and private, and which had organized themselves politically around symbolic representation and status. These feudal societies were transformed into a bourgeois liberal constitutional order which distinguished between the public and private realms; further, within the private realm, there was a bourgeois public sphere for rational-critical political debate which formed a new phenomenon called public opinion. Spearheading this shift was the growth of a literary public sphere in which the bourgeoisie learned to critically reflect upon itself and its role in society. This first major shift occurred alongside the rise of early non-industrial capitalism and the philosophical articulation of political liberalism by such thinkers as Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu (See: The Spirit of the Laws), Rousseau, and then Kant. The bourgeois public sphere flourished within the early laissez-faire, free-market, largely pre-industrial capitalist order of liberalism from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century.

The second part of Habermas' account traces the transition from the liberal bourgeois public sphere to the modern mass society of the social welfare state. Starting in the 1830s, extending from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, a new constellation of social, cultural, political, and philosophical developments took shape. Hegel's critique of Kant's liberal philosophy anticipated the shift, according to Habermas, and this shift came to a philosophical head in Marx's astute diagnosis of the contradictions inherent in the liberal constitutional social order. Habermas saw the modified liberalism of Mill and Tocqueville with their ambivalence toward the public sphere as emblematic manifestations of these contradictions.

Paralleling this philosophical progression against classical liberalism were major socio-economic transformations based on industrialization, and the result was the rise of mass societies characterized by consumer capitalism in the twentieth century. Clear demarcations between public and private and between state and society became blurred. The bourgeois public sphere was transformed by the increasing re-integration and entwining of state and society that resulted in the modern social welfare state. This shift, according to Habermas, can be seen as part of a larger dialectic in which political changes were made in an attempt to save the liberal constitutional order, but had the ultimate effect of destroying the bourgeois public sphere. He highlights the pernicious effects of commercialization and consumerization on the public sphere through the rise of mass media, public relations, and consumer culture. He delineates how these developments thwarted rational-critical political debate, including political parties functioning in a way that bypassed the public sphere, undermining parliamentary politics.[3]

Habermas drew on the cultural critiques of critical theory from the Frankfurt School,[4][5] which included important thinkers such as Theodor Adorno, who was one of his teachers at the Institute for Social Research from 1956 to 1959. Habermas began his habilitation during this period, but due to intellectual tensions with the Institute's director, philosopher and sociologist Max Horkheimer, he moved to the University of Marburg, where he completed the work under Wolfgang Abendroth.[6]

Reception

The book was reprinted many times in German and other languages, and has been enormously influential, especially since its translation into English, for scholars of political science, media studies, and rhetoric.[1] It is also an important work for historians of philosophy and scholars of intellectual history. After publication, Habermas was identified as an important philosopher of the twentieth century.

Since publication, the Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere has been critiqued for Habermas’s formulation of the concept of a public sphere which he claimed "stood or fell with the principle of universal access ... A public sphere from which specific groups would be eo ipso excluded was less than merely incomplete; it was not a public sphere at all." (Habermas 1962:85) However, the bourgeois public sphere required as preconditions of entry an excellent education and property ownership – which correlated to membership of the upper classes. Critics have argued that the bourgeois public sphere cannot be considered an ideal form of politics, since the public sphere was limited to upper-class strata of society and did not represent most of the citizens in these emerging nation-states.

Some critics claim the public sphere, as such, never existed, or existed only in the sense of excluding many important groups, such as the poor, women, slaves, migrants, and criminals. They maintain that the public sphere remains an idealized conception, little changed since Kant, since the ideal is still to a great extent what Habermas might call an unfinished project of modernity. (Cubitt 2005:93)

Similar critiques regarding the exclusivity of the bourgeois public sphere have been made by feminist and post-colonial authors.[7]

Notes

References

- Todd Gitlin (April 26, 2004). "Jurgen Habermas". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- David Randall (2008). "Ethos, Poetics, and the Literary Public Sphere". Modern Language Quarterly. Duke University Press. pp. 221–243. doi:10.1215/00267929-2007-033. 69(2). Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Jürgen Habermas (1991). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991. p. 175-177.

- Richard Lacayo; Joelle Attinger (November 18, 1985). "Law: Critical Legal Times at Harvard". Time Magazine. pp. 87–88. Preview at Time.com: (note: the preview displays an erroneous date of April 18, 2005, although the search results list shows the correct date).

- Wolf Heydebrand; Beverly Burris (1984). The Limits of Praxis in Critical Theory. In: Judith Marcus & Zoltán Tar (Eds.), Foundations of the Frankfurt School of Social Research (pp. 401-417). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books. p. 405.

- Matthew G. Specter (2010). Habermas: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 33.

- Nancy Fraser (1990) Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy, Social Text 25/26, 56-80.

Further reading

- Calhoun, Craig, ed. (1993). Habermas and the Public Sphere. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53114-3.

- Downie, J.A. “The Myth of the Bourgeois Public Sphere.” The Restoration and Eighteenth Century. Ed. Cynthia Wall. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. 58-79. Print.

External links

- Selected excerpts from The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

- Public Sphere Guide A Research Guide, Teaching Guide and Resource for the Renewal of the Public Sphere

- Transformations of the Public Sphere Essay Forum