The Tragedy of Tragedies

The Tragedy of Tragedies, also known as The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, is a play by Henry Fielding. It is an expanded and reworked version of one of his earlier plays, Tom Thumb, and tells the story of a character who is small in stature and status, yet is granted the hand of a princess in marriage; the infuriated queen and another member of the court subsequently attempt to destroy the marriage.

In adapting his earlier work Fielding incorporated significant plot changes; he also made the play more focused, and unified the type of satire by narrowing its critique of the abuses of language. Additionally, in a reaction to the view that Tom Thumb was a burlesque, Fielding replaced some of the humour in favour of biting satire. The play was first performed at the Haymarket Theatre on 24 March 1731, with the companion piece The Letter Writers. Critics enjoyed the play, but pointed out that it was originally designed as a companion piece to The Author's Farce.

Background

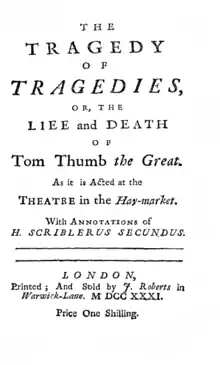

The Tragedy of Tragedies was an expanded and rewritten version of Tom Thumb. Fielding altered the play because although audiences enjoyed the play they did not notice the satire directed at the problems of contemporary theatre; the rewrite was intended to make the satire more obvious. The play was first performed on 24 March 1731 at the Haymarket Theatre in London, with the companion piece The Letter Writers. Its printed edition was "edited" and "commented" on by Fielding's pseudonym H. Scriblerus Secundus, who pretends not to be the original author.[1] It contains a frontispiece by Hogarth, which serves as the earliest proof of a relationship between Fielding and Hogarth.[2]

The printed edition was available on opening night and the notes included with the printed edition served as a way to explain the play. It was printed by James Roberts alongside of an edition of The Letter-Writers. The printed version of The Tragedy of Tragedies created two versions of the play, one that was acted and another that was to be read, and both contained humour catered to each.[3] Fielding believed modern tragedies to be superior to the Classic Greek tragedies because the Classics could only invoke pity and fear in the audience, while modern tragedies were able to leave the audience laughing at the ridiculous situations onstage. Fielding referred to these modern works as "laughing tragedies" and claimed that the only difference between his work and the modern tragedies was that his work was intentional in its laughter.[4] Fielding's play was later adapted into The Opera of Operas; or Tom Thumb the Great by playwrights Eliza Haywood and William Hatchett. It ran 13 nights at the Little Theatre starting 31 May 1733 and was discontinued because of the hot weather. It was later continued and had many shows during the seasons following.[5]

The Tragedy of Tragedies turned out to be one of Fielding's most enduring plays, with interesting later revivals. The novelist Frances Burney played Huncamunca in private productions of 1777, there was a private production done by the family of Jane Austen at Steventon in 1788, and professor William Kurtz Wimsatt Jr. played the giantess Glumdalca at a Yale University production in 1953.[6]

Cast

Cast according to the original printed billing:[7]

- King Arthur – "A passionate sort of King, Husband to Queen Dollallolla, of whom he stands a little in Fear; Father to Huncamunca, of whom he is very fond; and in Love with Glumdalca", played by Mr. Mullart

- Tom Thumb the Great – "A little Hero with a great Soul, something violent in his Temper, which is a little abated by his Love for Huncamunca", played by Young Verhuyck

- Ghost of Gaffar Thumb – "A whimsical sort of Ghost", played by Mr. Lacy

- Lord Grizzle – "Extremely zealous for the Liberty of the Subject, very cholerick in his Temper, and in Love with Huncaumunca", played by Mr. Jones

- Merlin – "A Conjurer, and in some sort Father to Tom Thumb", played by Mr. Hallam

- Noodle and Doodle – "Courtiers in Place, and consequently of that Part that is uppermost", Mr. Reynolds and Mr. Wathan

- Foodle – "A Courtier that is out of Place, and consequently of that Part that is undermost", played by Mr. Ayres

- Bailiff and Follower – "Of the Party of the Plaintiff", played by Mr. Peterson and Mr. Hicks

- Parson – "Of the Side of the Church", played by Mr. Watson

- Queen Dollallolla – "Wife to King Arthur, and Mother to Huncaumunca, a Woman entirely faultless, saving that she is little given to Drink; a little too much a Virago towards her Husband, and in Love with Tom Thumb", played by Mrs. Mullart

- The Princess Huncamunca – "Daughter to their Majesties King Arthur and Queen Dollallolla, of a very sweet, gentle, and amorous Disposition, equally in Love with Lord Grizzle and Tom Thumb, and desirous to be married to them both", played by Mrs. Jones

- Glumdalca – "of the Giants, a Captive Queen, belov'd by the King, but in Love with Tom Thumb", played by Mrs. Dove

- Cleora and Mustacha – "Maids of Honour, in Love with Noodle. Doodle." unlisted

- Other characters include Courtiers, Guards, Rebels, Drums, Trumpets, Thunder and Lightning

Plot

There is little difference between the general plot outline of Tom Thumb and The Tragedy of Tragedies, but Fielding does make significant changes. He completely removed a scene in which two doctors discuss Tom Thumb's death, and in doing so unified the type of satire that he was working on. He narrowed his critique to abuses of language produced only by individuals subconsciously, and not by frauds like the doctors. As for the rest of the play, Fielding expanded scenes, added characters, and turned the work into a three-act play. Merlin is added to the plot to prophesize Tom's end. In addition, Grizzle becomes Tom's rival for Huncamunca's heart, and a giantess named Glumdalca is added as a second love interest for both King Arthur and Tom. As the play progresses, Tom is not killed by Grizzle, but instead defeats him. However, Tom is killed by a giant, murderous cow offstage, the news of which prompts a killing spree, leaving seven dead bodies littered on stage and the King alone, left to boast that he is the last to fall, right before stabbing himself. The ghost of Tom in Tom Thumb is replaced by the ghost of Gaffar Thumb, Tom's father.[8]

Variorum

Fielding gives special emphasis to the printed version of The Tragedy of Tragedies by including notes and making it his only printed play that originally includes a frontispiece. The variorum, or notes, to the printed version of the play pointed out many of the parodies, allusions, and other references within The Tragedy of Tragedies. However, the notes themselves serve as a parody for serious uses of the notes and mock the idea of critically interpreting plays. By calling himself Scriblerus Secundus, Fielding connects The Tragedy of Tragedies with the works of the Scriblerus Club. These works also contain parodies of critics and scholars who attempt to elucidate literature.[9]

As such, the play is one of Fielding's Scriblerian plays, and the commentary in the print edition adds another level of satire that originates in the Scriblerus model of Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, et al. H. Scriblerus Secundus prefaces the play with claims that Scriblerus spent ten years working on an edition and that the play comes from the Elizabethan time period and may or may not have been the work of Shakespeare. Additionally, Scriblerus abuses classical sources through mistranslations and misreadings, botches contemporary and traditional critical theory, and is a satirical representation of criticism in general in the tradition of A Tale of a Tub and The Dunciad Variorum.[10] Regardless of the humorous elements, the notes do reveal Fielding's vast classical education.[11]

Fielding's theatrical output of 1730–1 shows that the assumption of the Scriblerian persona may have had an opportunist character. Though Fielding was happy to share in some of the fame and power of Pope and Swift at their peak, and to borrow some of their themes and techniques, he never agreed wholeheartedly with their cultural or political aims. In his poetry of the period Fielding distanced himself from the Toryism and misanthropy of Pope, and it has been suggested that the surface affiliation of The Tragedy of Tragedies with the writing of the Scriblerus Club masks real antipathy. However, Fielding's use of the Scriblerus name doesn't seem to have been resented by its creators. Swift reportedly praised Fielding as a wit, saying that he had laughed only twice in his life, the second instance being the Circumstance of Tom Thumb's killing the Ghost in the quick accumulation of corpses that closes the play. Pope may have echoed Fielding in the expanded four-book Dunciad of 1743 which suggests memories of Fielding's The Author's Farce in some of the methods it uses to satirise the garish culture of the time.[12]

Themes

The previous version, according to Fielding, was criticised as "a Burlesque on the loftiest Parts of Tragedy, and designed to banish what we generally call Fine Things, from the Stage."[13] This idea is developed by the focus of the tragedy being on a low-class citizen of the kingdom, even smaller in stature than a regular commoner. Tragedies normally deal with royalty and high-class families, so the focus on little Tom Thumb establishes the satirical nature from the beginning. In addition, the over the top nature of the plot, the intricacies of the characters' relationships, and the littering of bodies at the end of the play all serve to further mock and burlesque eighteenth century tragedies. The burlesque aspects posed a problem for Fielding, and people saw his show more for pleasure than for its biting satire. In altering his ending to having the ghost of Tom's father die instead of Tom's ghost, Fielding sought to remove part of the elements that provoked humour to bolster the satiric purpose of the play.[14]

Fielding rewrites many pieces of dialogue that originate in Tom Thumb, such as condensing Tom's description of the giants to Arthur. This condensing serves as Tom's rejection of the linguistic flourishes found within King Arthur's court that harm the English language as a whole. In both versions, the English language is abused by removing meaning or adding fake words to the dialogue to mimic and mock the dialogues of Colley Cibber's plays. The mocking and playing with language continues throughout; near the end of the play Arthur attacks similes in general:[15]

- Curst be the Man who first a Simile made!

- Curst, ev'ry Bard who writes! – So have I seen

- Those whose Comparisons are just and true,

- And those who liken things not like at all.[16]

Fielding's attacks on faulty language are not limited to internal events; he also pokes fun at Lewis Theobald. In particular, Fielding mocks Theobald's tragedy The Persian Princess and his notes on Shakespeare.[17]

Besides critiquing various theatrical traditions, there are gender implications in the dispute between King Arthur and his wife, Queen Dollallolla over which of the females should have Tom as her own. There are possible parallels between King Arthur and King George, and Queen Dollallolla and Queen Caroline, especially given the popular belief that Caroline influenced George's decision making. The gender roles were further complicated and reversed by the masculine Tom Thumb being portrayed by a female during many of the shows. This reversal allows Fielding to critique the traditional understanding of a hero within tragedy and gender roles in general. Hogarth's frontispiece reinforces what Fielding is attempting within The Tragedy of Tragedies by having the hero, Tom Thumb, unable to act as the two females take the dominant role and fight amongst themselves. Ultimately, gender was a way to comment on economics, literature, politics, and society as a whole along with reinforcing the mock-heroic nature of the play.[18]

Critical response

The Daily Post stated in April 1731 that there was a high demand to see the play. Notable individuals who attended the play, according to the 3 May Daily Post, included Princess Amelia and Princess Caroline. Such attendance and popularity among members of the royal court suggest that Fielding was not using the play to subtly criticise them.[19]

F. Homes Dudden argues that "As a burlesque of the heroics of Dryden and his school, The Tragedy of Tragedies is a singularly systematic, as well as brilliantly clever, performance."[20] The Battestins believe that "'The Tragedy of Tragedies – although circumstances prevented a run as prolonged as that of Tom Thumb a year earlier – was just as successful as its shorter, less elegant predecessor."[21] Albert J. Rivero opposes the critical focus on the Tragedy of Tragedies instead of its predecessor, Tom Thumb, because this oversight ignores how the play originated as a companion piece to The Author's Farce.[22]

Notes

- Rivero 1989 pp. 70–73

- Dudden 1966 p. 60

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 107

- Lewis 1987 p. 113

- Ingrassia 1998 pp. 106–107

- Keymer (2007) pp. 26–27

- Fielding 2004 pp. 547–548

- Rivero 1989 pp. 69–71

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 107–8

- Rivero 1989 pp. 74–75

- Paulson 2000 p. 54

- Keymer (2007) p. 28

- Hillhouse 1918 p. 42

- Rivero 1989 p. 72

- Rivero 1989 pp. 63–66

- Hillhouse 1918 p. 87

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 110

- Campbell 1995 pp. 19–22

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 108–109

- Dudden 1966 pp. 63–64

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 107

- Rivero 1989 pp. 53–54

References

- Campbell, Jill (1995), Natural Masques: Gender and Identity in Fielding's Plays and Novels, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-2391-6

- Dudden, F. Homes (1966), Henry Fielding: his Life, Works and Times, Archon Books

- Fielding, Henry (2004), Lockwood, Thomas (ed.), Plays: Vol. 1 (1728–1731), Clarendon Press

- Hillhouse, James Theodore, ed. (1918), The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, Yale University Press

- Ingrassia, Catherine (1998), Authorship, Commerce, and Gender in Early Eighteenth-Century England: A Culture of Paper Credit, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-63063-4

- Lewis, Peter Elfred (1987), Fielding's Burlesque Drama: Its Place in the Tradition, Edinburgh University Press

- Rivero, Albert (1992), The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career, University Press of Virginia, ISBN 978-0-8139-1228-8

- Keymer, Thomas (2007), "Theatrical Career", in Rawson, Claude (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Henry Fielding, Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–37, ISBN 978-0-521-67092-0