The World of Yesterday

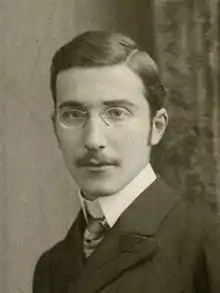

The World of Yesterday: Memories of a European (German title Die Welt von Gestern: Erinnerungen eines Europäers) is the memoir[1][2][3] of Austrian writer Stefan Zweig.[4] It has been called the most famous book on the Habsburg Empire.[5] He started writing it in 1934 when, anticipating Anschluss and Nazi persecution, he uprooted himself from Austria to England and later to Brazil. He posted the manuscript, typed by his second wife Lotte Altmann, to the publisher the day before they both committed suicide in February 1942. The book was first published in Stockholm (1942), as Die Welt von Gestern.[6] It was first published in English in April 1943 by Viking Press.[4] In 2011, Plunkett Lake Press reissued it in eBook form.[7] In 2013, the University of Nebraska Press published a translation by the noted British translator Anthea Bell.[8]

The book describes life in Vienna at the start of the 20th century with detailed anecdotes.[4] It depicts the dying days of Austria-Hungary under Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, including the system of education and the sexual ethics prevalent at the time, the same that provided the backdrop to the emergence of psychoanalysis. Zweig also describes the stability of Viennese society after centuries of Habsburg rule.

Chapters

| Chapter | Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | Preface |

| 2 | The world of security |

| 3 | School in the past century |

| 4 | Eros Matutinus |

| 5 | Universitas vitae |

| 6 | Paris, city of eternal youth |

| 7 | Bypaths on the way to myself |

| 8 | Beyond Europe |

| 9 | Light and shadows over Europe |

| 10 | The first hours of the 1914 war |

| 11 | The Struggle for Intellectual Brotherhood |

| 12 | In the heart of Europe |

| 13 | Homecoming to Austria |

| 14 | Into the world again |

| 15 | Sunset |

| 16 | Incipit Hitler |

| 17 | The agony of peace |

Detailed summary

Preface

Following the terrible events and upheavals experienced by his generation, Zweig sets out to write his autobiography. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through. He realizes that his past is "out of reach". Zweig makes it clear that his biography is based entirely on his memories.

The world of security

Stefan Zweig looks back on pre-war Austrian - and especially Viennese - society and writes about a time of security. Austria had a stable political system and a currency backed by gold and everyone could see themselves comfortably into the future. Many inventions revolutionized lives: the telephone, electricity and the car.

His father, originally from Moravia, made his fortune by running a small weaving factory. The author's mother comes from a wealthy Italian banking family, born in Ancona. His family represents the cosmopolitan "good Jewish bourgeoisie." But if the latter aspires to enrich themselves, this is not their purpose. The ultimate goal is to elevate oneself, morally, and spiritually. Also, it is the Jewish bourgeoisie that has primarily become a patron of Viennese culture. Vienna had become the city of culture, a city where culture was the primary concern. All Viennese had desirable tastes and were capable of making judgments of qualities. The artists, and especially the theater actors, were the only significant famous figures in Austria. Their concerns were trivialities given the events that followed which were unthinkable at that time.

The school in the last century

His time in school was quite unpleasant. Sport had a minimal place, performed in a dusty gymnasium. Zweig bitterly criticizes the old way of teaching, impersonal, cold, and distant.

In society, there was a certain distrust of young people.The author's father never hired young people, and the young tried to appear more mature, for example, by growing a beard. Respect for the elders was key. Zweig even claims that the school's purpose was to discipline and calm the youth's ardor.

However, in the face of this pressure, the students harbored a deep hatred towards vertical authority. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. All the pupils turned entirely to art: avid readers of literature and philosophy, listeners to concerts, spectators of plays, etc. The Viennese cafés played an essential role in the lives of these young students as a cultural center. Their passion gradually shifted away from the classics, and they became more interested in rising stars, especially young artists. A typical example of this aspiration is the case of Rainer Maria Rilke: a symbol of the whole movement of a victorious youth, completing the precocious genius Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

During this time, the first mass movements began to affect Austria, starting with the socialist movement, then the Christian Democratic Movement, and finally, the German Reich's unification movement. The anti-Semitic trend began to gain momentum, although it was still relatively moderate in its early stages.

Eros Matutinus

In this chapter, Zweig relates the transition to adulthood, puberty. During this phase, young boys, who until then accepted customary rules, reject conventions when they are not sincerely followed. Sexuality remains, although its century can no longer be considered pious, and that tolerance is now a central value, marred by an anarchic, disruptive aura.

According to Zweig, woman's clothes were intended to distort her figure, as well as to break her grace. But, by wanting to constrain the body, by wanting to hide the indecent, it is the opposite that occurs: what one tries to hide is exhibited. Young girls were watched continuously and occupied so that they could never think about sexuality.

Zweig notes that the situation has dramatically improved for both women and men. Women are now much freer, and men are no longer forced to live their sexuality in the shadows. He also recalls that venereal diseases - prevalent and dangerous at that time - fueled a real fear of infection. According to him, the generation that comes after him is much more fortunate than his in this regard.

Universitas vitae

After these high school years, Zweig recounts his transition to university. At this time, the university was crowned with a particular glory inherited from ancient privileges linked to its creation in the Middle Ages. According to Zweig, the ideal student was a scarred brute, often alcoholic, member of a student body.

Zweig went to college for the sole purpose of earning a doctorate in any field - to satisfy his family's aspirations - not to learn; To paraphrase Ralph Waldo Emerson, "good books replace the best universities." So he decides to study philosophy to give himself as much time as possible to discover other things. This chapter is, therefore, mainly devoted to what he did outside the university during his studies.

He began by collecting his first poems and looking for a publishing house to publish them. He enjoyed some success early on, to the point that Max Reger asked him for permission to set some of his poems to music. Later, he offered one of his works to the "Neue Freie Presse" - the cultural pages of reference in Austria-Hungary at that time - and had the honor of being published at only 19 years old. There he meets Theodor Herzl, for whom he nourishes a deep admiration. Of Jewish origin, like him, Herzl who attended the public impeachment of Dreyfus had published a text promoting the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine; the text was the object of intense criticism in Western Europe but was relatively well received in Eastern Europe.

He decides to continue his studies in Berlin to change the atmosphere, escape his young celebrity, and meet people beyond the circle of the Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna. Berlin began to attract and seek new talent, embracing novelty. He meets people from all walks of life, including the poet Peter Hille and anthroposophy Rudolf Steiner. He decides to translate poems and literary texts into his mother tongue to perfect his German.

It is Émile Verhaeren, who is the subject of a long digression. Zweig recounts his first meeting while visiting the studio of Charles van der Stappen. After speaking at length with him, he decides to make his work known by translating it, a task he observes as a duty and an opportunity to refine his literary talents.

After these many and rich encounters, he presented his thesis in philosophy.

Paris, the city of eternal youth

After finishing his studies, Zweig had promised to go to Paris to discover the city. Zweig launches into a lengthy description of the Parisian atmosphere, of the state of mind of Parisians. Paris represents the city where people of all classes, from all walks of life, come together, on an equal footing, the city where good humor and joviality reign.

He really discovered the city through the friendships he made, especially the one with Léon Bazalgette, to whom he was as close as a brother. He admired in him his sense of service, his magnanimity. - and also the simplest. Rilke is undoubtedly the one who impressed him the most by the aura he radiated and for whom he had tremendous respect. Zweig recounts several anecdotes about him, who takes it upon himself to paint a young man's portrait – or rather of a genius - compassionate, reserved, refined, and striving to remain discreet and temperate.

His meeting with Rodin also deeply marked him. That's when he said he received a great lesson in life: the great of this world are the best. He could see it at work, and he understood that creative genius requires total concentration, like Rodin. Rodin had given him a tour of his studio and his last still unfinished creation, then had begun to retouch his creation in his presence, and he had ended up forgetting it altogether.

Stefan Zweig then left Paris for London to improve his spoken English. Before leaving for London, he had the misfortune of having his suitcase stolen: but the thief was quickly found and arrested. Pity and a certain sympathy for the thief, Zweig had decided not to file a complaint, which earned him the whole neighborhood's antipathy, which he left rather quickly.

Unfortunately, in London, he doesn't really have the opportunity to meet many people and, therefore, discover the city. He did, however, attend the very well organized private reading of poems by William Butler Yeats. He also took away, on the advice of his friend Archibald GB Russell, a portrait of "King John" by William Blake, which he kept and which he never tired of admiring.

Bypaths on the way to myself

Zweig remembers his many travels and says that he has tried never to settle permanently in one place. If he considered this way of doing things as a mistake during his life, with hindsight, he recognizes that it allowed him to let go more quickly and accept losses without difficulty. His furniture was, therefore, reduced to what was necessary, without luxury. The only valuables he carries with him are autographs and other writings from authors he admires.

Stefan Zweig nurtures an almost religious devotion to the writings that preceded great artists' masterpieces, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His obsession is such that he boasts of having been able to meet Goethe's niece - on whom Goethe's gaze has lovingly rested.

He shares his participation in the Insel publishing house, whose deep respect and passion for works he admires. It is with this publishing house that he published his first dramas, notably Thersites. Zweig then recounts the strange twist of fate that has fallen on him and his creations. Four times, the performances that could have quickly propelled him to glory were stopped by the star actor or director's death. Zweig initially thought he was being chased by fate, but he recognizes afterward that it was only the fruit of chance and that, very often, chance takes on the appearance of destiny. The title of the chapter then takes on its meaning: it was by chance that he did not enter the golden books of literature for his talents as writers in versified dramas - things he would have liked - but for his novels. The detours of his life finally brought him back to his first vocation, that of a writer.

Beyond Europe

In retrospect, Zweig recognizes as more important to his life the men who brought him back to reality than those who turned it away for literature. This is particularly the case with Walther Rathenau, for whom he has a deep admiration. He considers him to be one of the smartest, most open, and polymath individuals. Rathenau only lacked a foundation, a global coherence which he acquired only when he had to save the German state - following the German defeat - with the ultimate aim of saving the 'Europe.

He has a bad memory of India because he saw the evils of discrimination of the Indian caste system at work. However, through the meetings he has made, he says he has learned a lot; this trip helped to take a step back to appreciate Europe better. He meets Karl Haushofer, whom he regards with high esteem during his journey, although he is saddened by the recovery of his ideas by the Nazi regime.

He then traveled to the United States, which left him with a powerful impression, even though many of the characteristics that made America what it is today had not yet emerged. He is pleased to see how easy it is for any individual to find work and make a living without asking for his origin, papers, or anything else. As he walks the streets, the display of one of his books in a bookstore takes away his abandonment feeling. He ended his trip to America by contemplating the Panama Canal's technical prowess: a titanic project, costly - especially in human lives - started by the Europeans and completed by the Americans.

Light and shadows over Europe

Zweig understands that it can be difficult for a generation to live through crises and catastrophes to conceive previous generations' optimism. They witnessed a rapid improvement in living conditions, a series of discoveries and innovations, a liberation of mores and youth. Progress in transport had upset the maps; the air's conquest had called into question the meaning of borders. Widespread optimism gave everyone ever-growing confidence, as it thwarted any attempt to seek peace - each believing that the other side valued peace more than anything else.

The artists and the new youth were devoted to the European cause, to peace between nations, but no one took seriously the gradually emerging threats. All were content to remain in a generalized idealism.

Stefan Zweig strives to restore the prevailing atmosphere through the recounting of small events. The Redl affair represents the first event in which tensions were palpable. The next day, he ran into Bertha von Suttner, who foretold the turn of events:

It was when he went to the cinema in the small town of Tours that he was amazed to see that the hatred - displayed against Kaiser Wilhelm II - had already spread throughout France. But he left despite everything confident in Vienna, already having in mind what he intended to achieve in the coming months. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing.

The first hours of the war of 1914

According to Zweig, the summer of 1914 would have been unforgettable by its sweetness and its beauty. The news of the death of Franz Ferdinand of Austria, although it hurt the faces of those who had just learned about it at the time, did not leave lasting traces. Franz Ferdinand was hardly appreciated, and Zweig himself found him cold, distant, unfriendly. Strangely, what is the most controversial at this time is his funeral: he had entered into a misalliance, and it was unacceptable that his wife and children could rest with the rest of the Habsburgs.

The world never imagined that a war could break out. Zweig had visited a few days before the declaration of war with friends in Belgium. Even seeing the Belgian soldiers, Zweig was convinced that Belgium would not be attacked. Then ominous events multiplied until the outbreak of war with the declaration of war by Austria against Serbia.

The young soldiers went cheerfully to the front, to the cheers of the crowd. National solidarity and brotherhood were at their peak. In comparison with the abatement of 1939, this enthusiasm for war is explained by an idealization of war, possible by its great temporal distance, by the heightened optimism of the century, and the almost blind confidence in governments' honesty. This enthusiasm quickly turned into a deep hatred towards the enemies of the fatherland.

Zweig does not take part in this widespread hatred, as he knows the now rival nations too well to hate them overnight. Physically unfit to go to the front, he committed his forces to work as a librarian within the military archives. He sees his whole country sinking in the apology of the opposing camp's deep and sincere hatred, like the poet Ernst Lissauer, author of the Song of hatred against England. Zweig, rejected by his friends who consider him almost a traitor to his nation, for his part, undertakes a personal war against this murderous passion.

The Struggle for Intellectual Brotherhood

Zweig makes it his mission, rather than only not taking part in this hatred, to actively fight against this propaganda, less to convince than to spread his message simply. He succeeded in having an article published in the "Berliner Tageblatt," urging them to remain faithful to friendships beyond borders. Shortly after, he receives a letter from his friend Rolland, and the two decide to promote reconciliation. They tried to organize a conference bringing together the great thinkers of all nations to encourage mutual understanding. They continued their commitment through their writings, comforting those who were in despair in this dark time.

Zweig then took the opportunity to observe the ravages of war with his own eyes on the Russian front. He sees the dramatic situation in which the soldiers find themselves; he considers the solidarity formed between the soldiers of the two camps who feel powerless in the face of the events they are going through. He is initially shocked to see that officers far from the front can walk almost carefree with young ladies several hours by train from the front. But very quickly, he forgives them because the real culprits are those who, in his eyes, encourage the feeling of hatred towards the "enemy."

He decides to fight this propaganda by writing a drama, taking up Biblical themes, particularly Jewish wanderings, trials, praising the losers' destiny. He produced this work to free himself from the weight of the censorship imposed on him by society.

In the heart of Europe

When he published his drama "Jérémie" in October 1917, he expects poor reception. To his surprise, his work was very well received, and he was offered to conduct its representation in Zurich. Therefore, he decides to leave for Switzerland, a rare neutral country in Europe's heart. On his journey to Switzerland, he met two Austrians in Salzburg who would play a significant role once Austria had surrendered: Heinrich Lammasch and Ignaz Seipel. These two pacifists had planned and convinced the Emperor of Austria to negotiate a separate peace if the Germans refused to make peace.

When Zweig crosses the border, he is immediately relieved, and he feels relieved of a burden, happy to enter a country at peace. Once in Switzerland, he is pleased to find his friend Rolland and other French acquaintances and feel fraternally united. During his stay, it was the figure of the director of the anti-militarist newspaper "Demain" Henri Guilbeaux who marked him deeply, because it was in him that he saw a historical law being verified: in intense periods, simple men could exceptionally become central figures of a current - here, that of the anti-militarists during the First World War. He has the opportunity to see many refugees who could not choose their camps, torn by war at the James Joyce.

After the relative success of his play, he gradually realizes that Switzerland is not only a land of refuge but the theater of a game of espionage and counter-espionage. During his stay, the German and Austrian defeat becomes more and more inevitable, and the world begins to rejoice in the chorus of a finally better and more human world.

Homecoming to Austria

Once the German and Austrian defeat has been confirmed, Zweig decides to join his country in ruins, driven by a kind of patriotic impulse: he gives himself the mission of helping his country accept its defeat. His return is the subject of a long preparation since winter is approaching, and the country is now in the greatest need. On his return, he attends the last Austrian emperor's departure in the station, a milestone for an Austrian for whom the emperor was the central Austrian figure.

Then begins the bitter observation of a generalized regression of life; everything of value has been stolen, such as leather, copper, and nickel. The trains are in such bad condition that the journey times are considerably extended. Once at home in Salzburg, in residence he bought during the war, he must face everyday life made difficult by shortages and cold - when his roof is ripped through and repairs made impossible by the scarcity. He watches helplessly the devaluation of the Austrian crown and inflation, the loss of quality of all products, paradoxical situations, the invasion of foreigners who profit from the depreciation of the Austrian currency, etc.

Paradoxically, theaters, concerts, and operas are active, and artistic and cultural life is in full swing: Zweig explains this by the general feeling that this could be the last performance. Also, the young generation rebels against the old authority and rejects everything at once: homosexuality becomes a sign of protest, young writers think outside the box, painters abandon classicism for cubism and surrealism. . Meanwhile, Zweig set himself the task of reconciling the European nations by taking care of the German side. First alongside Henri Barbusse, then alone on his side, after the communist radicalization of Barbusse's newspaper, Clarté.

Into the world again

After surviving the three years after the war in Salzburg, Austria, he decided to travel with his wife to Italy once the situation improved sufficiently. Full of apprehension about the reception we reserve for an Austrian, he is surprised by the Italians' hospitality and thoughtfulness, telling himself that the masses had not changed profoundly because of the propaganda. There he met his poet friend Giuseppe Antonio Borgese and his painter friend Alberto Stringa. Zweig admits to being at that moment still lulled by the illusion that the war is over, although he has the opportunity to hear young Italians singing Giovinezza.

He then goes to Germany. He has time to see his friend Rathenau, who is now Minister of Foreign Affairs, for the last time. He admires this man who knows full well that only time can heal the wounds left by war. After the assassination of Rathenau, Germany sank into hyperinflation, debauchery, and disorder. According to Zweig, this sad episode was decisive for the rise of the Nazi Party.

Zweig has the chance to experience unexpected success and to be translated into several languages. He reads a lot and hardly appreciates redundancies, heavy styles, etc., preferences that are found in his style: he says he writes in a fluid manner, such as the words come to mind. He says he has carried out important synthesis work - notably with Marie-Antoinette - and sees his capacity for conciseness as a defining element of his success. He knows the pleasure of seeing Maxim Gorky, whom he already admired at school, write the preface to one of his works.

While he recognizes that this success fills him with joy when he touches his works and works, he refuses to be the object of admiration for his appearance. He naively enjoys his fame at first on his travels, but it begins to weigh on him. So he wishes he had started to write and publish under a pseudonym to enjoy his celebrity in all serenity.

Sunset

Zweig says that before Hitler came to power, people had never traveled so much in Europe. He himself continues to travel at this time, particularly about his career and fame as a writer. Despite his success, Zweig says he remains humble and does not really change his habits: he continues to stroll with his friends in the streets, he does not disdain to go to the provinces to stay in small hotels.

If there's one trip that taught him a lot, it's the one to Russia. Russia had always been on his list, but he still did his best to remain politically neutral. He has the opportunity to officially go to Russia in an unbiased way: the birthday of Leo Tolstoy, a great Russian writer. At first, fascinated by the authenticity of the inhabitants, their friendliness, and their warm welcome, by the profound simplicity of Tosltoï's tomb, he left with great caution. Following one of the parties, he realizes that someone has slipped him a letter in French, warning him of the propaganda of the Soviet regime. He begins to reflect on the intellectual stimulation that exile can promote.

Later, he had the opportunity to use his celebrity to ask a favor of Benito Mussolini, that to spare the life of Giuseppe Germani. His wife had begged the writer to intervene, to put pressure on Mussolini by organizing an international protest. Zweig preferred to send a letter personally to Duce, and Mussolini granted his request.

Back in Salzburg, he was impressed by the cultural scope that the city had taken, which had become the artistic center of Europe. It thus has the opportunity to welcome the great names of literature and painting. This allows him to complete his collection of autographs and first drafts. Zweig looks back on this passion of which he boasts of his expertise and admits to seeking, above all, the secrets of the creation of masterpieces. Unfortunately, with Hitler's rise to power, his collection gradually fell apart.

Before these tragic events, Zweig reveals to have wondered about his success, a success he had not ardently desired. A thought crossed him at this time, after having acquired a secure, enviable and - he believed - lasting position:

Wäre es nicht besser für mich - so träumte es in mir weiter - etwas anderes käme, etwas Neues, etwas das mich unruhiger, gespannter, das mich jünger machte, indem es mich herausforderte zu neuem und vielleicht noch gefährlicherem Kampf?

- Zweig, Sonnenuntergang, Die Welt von Gestern (1942)

"Wouldn't it be better for me - so that thought continued within me - if something else happened, something new, something that troubles me, torments me, rejuvenates me, demanding of me a new and can -be still a dangerous fight? "

His rash wish, resulting from a "volatile thought" - in his words - came true, shattering everything, him, and what he had accomplished.

Incipit Hitler

Stefan Zweig begins by stating a law: no witness to significant changes can recognize them at their beginnings. The name "Hitler" has long been one agitator's name among many others in this turbulent period shaken by numerous coup attempts. However, very well organized young men had already started to cause trouble, wearing Nazi insignia. Even after their failed coup, their existence quickly faded into oblivion. It was unthinkable when Germany imagined that a man as uneducated as Hitler could come to power. Zweig explains this success thanks to the many promises he made to almost all parties; everyone thought they could use Hitler.

Zweig had told his publisher as soon as the Reichstag was burnt down - something he did not believe possible - that his books would be banned. He then describes the progressive censorship set up to that of his opera ( Die schweigsame Frau ) produced with the composer Richard Strauss, whose infallible lucidity and regularity he admires at work. Due to Zweig's politically neutral writings, it was impossible to censor his opera, knowing that it was difficult to censor the most significant German composer still alive. After having read Zweig's opera, Hitler himself exceptionally authorizes the performance and attends it in person. However, after a letter - intercepted by the Gestapo - Strauss' too sincere about his place as President of the Reich Music Chamber, the opera is censored, and Strauss is forced to give up his position.

During the first troubles, Zweig went to France, then to England, where he undertakes the biography of Marie Stuart, noting the absence of an objective and good quality biography. Once completed, he returns to Salzburg, where he "witnesses" the critical situation in which his country finds itself: it is at this moment that he realizes how much, even living in a city shaken by shootings, foreign newspapers are better informed than he is about the Austrian situation. He chooses to bid farewell to London when the police decide to search his residence, which was previously unthinkable in the rule of law, which guarantees individual freedom.

The agony of peace

Zweig begins with a quote that sets the tone for the last chapter :

The sun of Rome is set. Our day is gone.Clouds, dews and dangers come; our deeds are done.

- William Shakespeare ,

Like Gorky's exile, his exile is not yet a real exile. He still has his passport and may well return to Austria. Knowing full well that he can't have any influence in England - having failed in his own country - he resolves to be silent no matter the trials. During his stay, he could attend a memorable debate between HG Wells and Bernard Shaw, two great men he gave a long and admiring description.

Invited for a PEN-Club conference, he had the opportunity to stop in Vigo, then in General Franco's hands. He once again noted with bitterness the recruitment of young people dressed by the fascist forces. Once in Argentina, seeing the Hispanic heritage still intact, he regains hope. He praises Brazil, the last host country, a land that does not consider the origins, and says he sees Europe's future.

He had the opportunity to follow Austria's annexation when his friends, then living there, firmly believed that the neighboring countries would never passively accept such an event. Clairvoyant, Zweig had already said goodbye in autumn 1937 to his mother and the rest of his family. He then embarked on a difficult period to endure both the loss - and worse - of his family in Austria surrendered to Nazi barbarism and nationality loss.

From the peace negotiated with the Munich Agreements, Zweig suspected that any negotiation with Hitler was impossible, that the latter would break his commitments at the right time. But he preferred to be silent. He has the chance to see his friend Sigmund Freud again, who has managed to reach England. It is a great pleasure for him to speak with him again, a scholar whose work he admires and his entire dedication to the cause of truth. He attended his funeral shortly after.

Stefan Zweig then develops a long questioning on the meaning of the trials and the horrors that the Jews - and those designated as such - go through, yet all so different. As he prepares to get married, Hitler declares war on Poland, and the gear forces England to follow, making him, like all foreigners in his case, "foreign enemies." He, therefore, prepares his affairs to leave England. He ends his work by admitting to being constantly pursued by the shadow of war, and by a sentence intended to be consoling:

Aber jeder Schatten ist im letzten doch auch Kind des Lichts, und nur wer Helles und Dunkles, Krieg und Frieden, Aufstieg und Niedergang erfahren, nur der hat wahrhaft gelebt.

- Zweig, Die Agonie des Friedens, Die Welt von Gestern

"But every shadow is ultimately also the daughter of light and only he who has known light and darkness, war and peace, rise and fall, only this one has truly lived. "

According to Zweig, earlier European societies, where religion (i.e., Christianity) had a central role, condemned sexual impulses as work of the devil. The late 19th century had abandoned the devil as an explanation of sexuality; hence it lacked a language able to describe and condemn sexual impulses. Sexuality was left unmentioned and unmentionable, though it continued to exist in a parallel world that could not be described, mostly prostitution. Fashion contributed to this peculiar oppression by denying the female body and constraining it within corsets.

The World of Yesterday details Zweig's career before, during, and after World War I. Of particular interest are Zweig's description of various intellectual personalities, including Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism, Rainer Maria Rilke, the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren, the composer Ferruccio Busoni, the philosopher and antifascist Benedetto Croce, Maxim Gorky, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Arthur Schnitzler, Franz Werfel, Gerhart Hauptmann, James Joyce, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner, the German industrialist and politician Walther Rathenau and the pacifist and friend Romain Rolland. Zweig also met Karl Haushofer during a trip to India. The two became friends. Haushofer was the founder of geopolitics and became later an influence on Adolf Hitler. Always aloof from politics, Zweig overlooked the dark potential of Haushofer's thought; he was surprised when later told of links between Hitler and Haushofer.

Zweig particularly admired the poetry of Hugo von Hofmannsthal and expressed this admiration and Hofmannsthal's influence on his generation in the chapter devoted to his school years:

"The appearance of the young Hofmannsthal is and remains notable as one of the greatest miracles of accomplishment early in life; in world literature, except for Keats and Rimbaud, I know no other youthful example of a similar impeccability in the mastering of language, no such breadth of spiritual buoyancy, nothing more permeated with a poetic substance even in the most casual lines, than in this magnificent genius, who already in his sixteenth and seventeenth year had inscribed himself in the eternal annals of the German language with unextinguishable verses and prose which today has still not been surpassed. His sudden beginning and simultaneous completion was a phenomenon that hardly occurs more than once in a generation."

— Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von Gestern, Frankfurt am Main 1986, 63–64

Notable episodes include the Austrian public's reaction to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo in 1914, the departure from Austria by a train of the last Emperor Charles I of Austria in 1918, the beginning of the Salzburg festival and the Austrian hyperinflation of 1921–22. Zweig admitted that as a young man, he had not recognized the coming danger of the Nazis, who started organizing and agitating in Austria in the 1920s. Zweig was a committed pacifist but hated politics and shunned political engagement. His autobiography shows some reluctance to analyze Nazism as a political ideology; he tended simply to regard it as the rule of one particularly evil man, Hitler. Zweig was struck that the Berghof, Hitler's mountain residence in Berchtesgaden, an area of early Nazi activity, was just across the valley from his own house outside Salzburg. Zweig believed strongly in Europeanism against nationalism.

Zweig also describes his passion for collecting manuscripts, mostly literary and musical.

Zweig collaborated in the early 1930s with composer Richard Strauss on the opera Die schweigsame Frau, which is based on a libretto by Zweig. Strauss was then admired by the Nazis, who were not happy that their favorite composer's new opera had a Jewish author's libretto. Zweig recounts that Strauss refused to withdraw the opera and even insisted that Zweig's authorship of the libretto be credited; the first performance in Dresden was said to have been authorized by Hitler himself. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The run was interrupted after the second performance, as the Gestapo had intercepted a private letter from Strauss to Zweig. The elderly composer invited Zweig to write the libretto for another opera. According to Zweig, this led to Strauss's resignation as president of the Reichsmusikkammer, the Nazi state institute for music.

Nothing is said of Zweig's first wife; his second marriage is briefly touched upon. The tragic effects of contemporary antisemitism are discussed, but Zweig does not analyze in detail his Jewish identity. Zweig's friendship with Sigmund Freud is described towards the end, particularly while both lived in London during the last year of Freud's life. The book finishes with the news of the start of World War II, while he was waiting for some travel documents at a counter of Bath’s General Register Office.

"When I attempt to find a simple formula for the period in which I grew up, before the First World War, I hope that I convey its fullness by calling it the Golden Age of Security."[4]

Adaptations

- 2016 : Le monde d'hier by Laurent Seksik , directed by Patrick Pineau and Jérôme Kircher at the Théâtre de Mathurins in Paris.

References

- Jones, Lewis (11 January 2010), "The World of Yesterday", The Telegraph, retrieved 2 November 2015

- Lezard, Nicholas (4 December 2009), "The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig", The Guardian, retrieved 2 November 2015

- Brody, Richard (14 March 2014), "Stefan Zweig, Wes Anderson, and a Longing for the Past", The New Yorker, retrieved 2 November 2015

- The World of Yesterday, Viking Press.

- Giorgio Manacorda (2010) Nota bibliografica in Joseph Roth, La Marcia di Radetzky, Newton Classici quotation:

Stefan Zweig, l'autore del più famoso libro sull'Impero asburgico, Die Welt von Gestern

- Darién J. Davis, Oliver Marshall (ed.), Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil, 1940–42, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010, p. 41.

- "The World of Yesterday". Plunkett Lake Press.

- https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9780803226616//

External links

- The World of Yesterday at Faded Page (Canada)