Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), better known as Rainer Maria Rilke (German: [ˈʁaɪnɐ maˈʁiːa ˈʁɪlkə]), was a Bohemian-Austrian poet and novelist. He is "widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense German-language poets".[1] He wrote both verse and highly lyrical prose.[1] Several critics have described Rilke's work as "mystical".[2][3] His writings include one novel, several collections of poetry and several volumes of correspondence in which he invokes images that focus on the difficulty of communion with the ineffable in an age of disbelief, solitude and anxiety. These themes position him as a transitional figure between traditional and modernist writers.

Rainer Maria Rilke | |

|---|---|

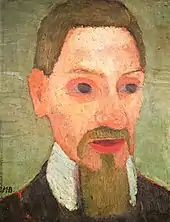

Rilke in 1900 | |

| Born | René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke 4 December 1875 Prague, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 29 December 1926 (aged 51) Montreux, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist |

| Language | German, French |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Period | 1894–1925 |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

Rilke travelled extensively throughout Europe (including Russia, Spain, Germany, France and Italy) and, in his later years, settled in Switzerland – settings that were key to the genesis and inspiration for many of his poems. While Rilke is most known for his contributions to German literature, over 400 poems were originally written in French and dedicated to the canton of Valais in Switzerland. Among English-language readers, his best-known works include the poetry collections Duino Elegies (Duineser Elegien) and Sonnets to Orpheus (Die Sonette an Orpheus), the semi-autobiographical novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge), and a collection of ten letters that was published after his death under the title Letters to a Young Poet (Briefe an einen jungen Dichter). In the later 20th century, his work found new audiences through use by New Age theologians and self-help authors[4][5][6] and frequent quotations by television programs, books and motion pictures.[7] In the United States, Rilke remains among the more popular, best-selling poets.[8]

Biography

Early life (1875–1896)

He was born René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke in Prague, capital of Bohemia (then part of Austria-Hungary, now part of Czechia). His childhood and youth in Prague were not especially happy. His father, Josef Rilke (1838–1906), became a railway official after an unsuccessful military career. His mother, Sophie ("Phia") Entz (1851–1931), came from a well-to-do Prague family, the Entz-Kinzelbergers, who lived in a house on the Herrengasse (Panská) 8, where René also spent many of his early years. The relationship between Phia and her only son was coloured by her mourning for an earlier child, a daughter who had died only one week old. During Rilke's early years, Phia acted as if she sought to recover the lost girl through the boy by treating him as if he were a girl. According to Rilke, he had to wear "fine clothes" and "was a plaything [for his mother], like a big doll".[9][10][11][lower-alpha 1] His parents' marriage failed in 1884. His parents pressured the poetically and artistically talented youth into entering a military academy in Sankt Pölten, Lower Austria, which he attended from 1886 until 1891, when he left owing to illness. He moved to Linz, where he attended trade school. Expelled from school in May 1892, the 16-year-old prematurely returned to Prague. From 1892 to 1895, he was tutored for the university entrance exam, which he passed in 1895. Until 1896, he studied literature, art history, and philosophy in Prague[13] and Munich.[14]

Munich and Saint Petersburg

Rilke met and fell in love with the widely travelled, intellectual woman of letters, Lou Andreas-Salomé in 1897 in Munich. He changed his first name from "René" to "Rainer" at Salomé's urging, because she thought that name to be more masculine, forceful and Germanic.[15] His relationship with this married woman, with whom he undertook two extensive trips to Russia, lasted until 1900. Even after their separation, Salomé continued to be Rilke's most important confidante until the end of his life. Having trained from 1912 to 1913 as a psychoanalyst with Sigmund Freud, she shared her knowledge of psychoanalysis with Rilke.

In 1898 Rilke undertook a journey lasting several weeks to Italy. The following year he travelled with Lou and her husband, Friedrich Carl Andreas, to Moscow where he met the novelist Leo Tolstoy. Between May and August 1900, a second journey to Russia, accompanied only by Lou, again took him to Moscow and Saint Petersburg, where he met the family of Boris Pasternak and Spiridon Drozhzhin, a peasant poet. Author Anna A. Tavis cites the cultures of Bohemia and Russia as the key influences on Rilke's poetry and consciousness.[16]

In 1900, Rilke stayed at the artists' colony at Worpswede. (Later, his portrait would be painted by the proto-expressionist Paula Modersohn-Becker, whom he got to know at Worpswede.) It was here that he got to know the sculptor Clara Westhoff, whom he married the following year. Their daughter Ruth (1901–1972) was born in December 1901.

Paris (1902–1910)

In the summer of 1902, Rilke left home and travelled to Paris to write a monograph on the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Before long his wife left their daughter with her parents and joined Rilke there. The relationship between Rilke and Clara Westhoff continued for the rest of his life; a mutually-agreed-upon effort towards a divorce was bureaucratically hindered by the fact that Rilke was a Catholic, albeit a non-practising one.

At first, Rilke had a difficult time in Paris, an experience that he called upon in the first part of his only novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. At the same time his encounter with modernism was very stimulating: Rilke became deeply involved with the sculpture of Rodin and then the work of Paul Cézanne. For a time, he acted as Rodin's secretary, also lecturing and writing a long essay on Rodin and his work. Rodin taught him the value of objective observation and, under this influence, Rilke dramatically transformed his poetic style from the subjective and sometimes incantatory language of his earlier work into something quite new in European literature. The result was the New Poems, famous for the "thing-poems" expressing Rilke's rejuvenated artistic vision. During these years, Paris increasingly became the writer's main residence.

The most important works of the Paris period were Neue Gedichte (New Poems) (1907), Der Neuen Gedichte Anderer Teil (Another Part of the New Poems) (1908), the two "Requiem" poems (1909), and the novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, started in 1904 and completed in January 1910.[17]

During the later part of this decade, Rilke spent extended periods in Ronda, the famous bullfighting centre in southern Spain, where he kept a permanent room at the Hotel Reina Victoria from December 1912 to February 1913.[18][19]

Duino and the First World War (1911–1919)

Between October 1911 and May 1912, Rilke stayed at the Castle Duino, near Trieste, home of Princess Marie of Thurn und Taxis. There, in 1912, he began the poem cycle called the Duino Elegies, which would remain unfinished for a decade because of a long-lasting creativity crisis. Rilke had developed an admiration for El Greco as early as 1908, so he visited Toledo during the winter of 1912/13 to see Greco's paintings. It has been suggested that Greco's manner of depicting angels influenced the conception of the angel in the Duino Elegies.[20] The outbreak of World War I surprised Rilke during a stay in Germany. He was unable to return to Paris, where his property was confiscated and auctioned. He spent the greater part of the war in Munich. From 1914 to 1916 he had a turbulent affair with the painter Lou Albert-Lasard. Rilke was called up at the beginning of 1916 and had to undertake basic training in Vienna. Influential friends interceded on his behalf – he was transferred to the War Records Office and discharged from the military on 9 June 1916. He returned to Munich, interrupted by a stay at Hertha Koenig's manor Gut Bockel in Westphalia. The traumatic experience of military service, a reminder of the horrors of the military academy, almost completely silenced him as a poet.[21]

Switzerland and Muzot (1919–1926)

On 11 June 1919, Rilke travelled from Munich to Switzerland. The outward motive was an invitation to lecture in Zurich, but the real reason was the wish to escape the post-war chaos and take up his work on the Duino Elegies once again. The search for a suitable and affordable place to live proved to be very difficult. Among other places, Rilke lived in Soglio, Locarno and Berg am Irchel. It was only in mid-1921 that was he able to find a permanent residence in the Château de Muzot in the commune of Veyras, close to Sierre in Valais. In an intense creative period, Rilke completed the Duino Elegies in several weeks in February 1922. Before and after this period, Rilke rapidly wrote both parts of the poem cycle Sonnets to Orpheus containing 55 entire sonnets. Together, these two have often been taken as constituting the high points of Rilke's work. In May 1922, Rilke's patron Werner Reinhart bought and renovated Muzot so that Rilke could live there rent-free.[22]

During this time, Reinhart introduced Rilke to his protégée, the Australian violinist Alma Moodie.[23] Rilke was so impressed with her playing that he wrote in a letter: "What a sound, what richness, what determination. That and the Sonnets to Orpheus, those were two strings of the same voice. And she plays mostly Bach! Muzot has received its musical christening ..."[23][24][25]

From 1923 on, Rilke increasingly struggled with health problems that necessitated many long stays at a sanatorium in Territet near Montreux on Lake Geneva. His long stay in Paris between January and August 1925 was an attempt to escape his illness through a change in location and living conditions. Despite this, numerous important individual poems appeared in the years 1923–1926 (including Gong and Mausoleum), as well as his abundant lyrical work in French. His book of French poems Vergers was published in 1926.

In 1924 Erika Mitterer began writing poems to Rilke, who wrote back with approximately 50 poems of his own and called her verse a Herzlandschaft (landscape of the heart).[26] This was the only time Rilke had a productive poetic collaboration throughout all his work.[27] Mitterer also visited Rilke.[28] In 1950 her Correspondence in Verse with Rilke was published and received much praise.[29]

Rilke supported the Russian Revolution in 1917 as well as the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919.[30] He became friends with Ernst Toller and mourned the deaths of Rosa Luxemburg, Kurt Eisner, and Karl Liebknecht.[31] He confided that of the five or six newspapers he read daily, those on the far left came closest to his own opinions.[32] He developed a reputation for supporting left-wing causes and thus, out of fear for his own safety, became more reticent about politics after the Bavarian Republic was crushed by the right-wing Freikorps.[32] In January and February 1926, Rilke wrote three letters to the Mussolini-adversary Aurelia Gallarati Scotti in which he praised Benito Mussolini and described fascism as a healing agent.[33][34][35]

Death and burial

Shortly before his death, Rilke's illness was diagnosed as leukemia. He suffered ulcerous sores in his mouth, pain troubled his stomach and intestines, and he struggled with increasingly low spirits.[36] Open-eyed, he died in the arms of his doctor on December 29, 1926, in the Valmont Sanatorium in Switzerland. He was buried on January 2, 1927, in the Raron cemetery to the west of Visp.[36]

Rilke had chosen as his own epitaph this poem:

Rose, oh reiner Widerspruch, Lust,

Niemandes Schlaf zu sein unter soviel

Lidern.

Rose, o pure contradiction, desire

to be no one's sleep beneath so many

lids.

A myth developed surrounding his death and roses. It was said: "To honour a visitor, the Egyptian beauty Nimet Eloui Bey, Rilke gathered some roses from his garden. While doing so, he pricked his hand on a thorn. This small wound failed to heal, grew rapidly worse, soon his entire arm was swollen, and his other arm became affected as well", and so he died.[36]

Writings

The Book of Hours

Rilke's three complete cycles of poems that constitute The Book of Hours (Das Stunden-Buch) were published by Insel Verlag in April 1905. These poems explore the Christian search for God and the nature of Prayer, using symbolism from Saint Francis and Rilke's observation of Orthodox Christianity during his travels in Russia in the early years of the twentieth century.

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

Rilke wrote his only novel, Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (translated as The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge), while living in Paris, completing the work in 1910. This semi-autobiographical novel adopts the style and technique that became associated with Expressionism which entered European fiction and art in the early 20th century. He was inspired by Sigbjørn Obstfelder's work A Priest's Diary and Jens Peter Jacobsen's novel Niels Lyhne (1880) which traces the fate of an atheist in a merciless world. Rilke addresses existential themes, profoundly probing the quest for individuality and the significance of death and reflecting on the experience of time as death approaches. He draws considerably on the writings of Nietzsche, whose work he came to know through Lou Andreas-Salomé. His work also incorporates impressionistic techniques that were influenced by Cézanne and Rodin (to whom Rilke was secretary in 1905–1906). He combines these techniques and motifs to conjure images of mankind's anxiety and alienation in the face of an increasingly scientific, industrial and reified world.

Duino Elegies

Rilke began writing the elegies in 1912 while a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis (1855–1934) at Duino Castle, near Trieste on the Adriatic Sea. During this ten-year period, the elegies languished incomplete for long stretches of time as Rilke suffered frequently from severe depression, some of which was caused by the events of World War I and his conscripted military service. Aside from brief episodes of writing in 1913 and 1915, Rilke did not return to the work until a few years after the war ended. With a sudden, renewed inspiration – writing in a frantic pace he described as "a savage creative storm" – he completed the collection in February 1922 while staying at Château de Muzot in Veyras, in Switzerland's Rhône Valley. After their publication and his death shortly thereafter, the Duino Elegies were quickly recognized by critics and scholars as Rilke's most important work.[37][38]

The Duino Elegies are intensely religious, mystical poems that weigh beauty and existential suffering.[39] The poems employ a rich symbolism of angels and salvation but not in keeping with typical Christian interpretations. Rilke begins the first elegy in an invocation of philosophical despair, asking: "Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the hierarchies of angels?" (Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen?)[40] and later declares that "every angel is terrifying" (Jeder Engel ist schrecklich).[41] While labelling of these poems as "elegies" would typically imply melancholy and lamentation, many passages are marked by their positive energy and "unrestrained enthusiasm".[37] Together, the Duino Elegies are described as a metamorphosis of Rilke's "ontological torment" and an "impassioned monologue about coming to terms with human existence" discussing themes of "the limitations and insufficiency of the human condition and fractured human consciousness ... man's loneliness, the perfection of the angels, life and death, love and lovers, and the task of the poet".[42]

Sonnets to Orpheus

With news of the death of Wera Knoop (1900–1919), his daughter's friend, Rilke was inspired to create and set to work on Sonnets to Orpheus.[43] In 1922, between February 2 and 5, he completed the first section of 26 sonnets. For the next few days he focused on the Duino Elegies, completing them on the evening of February 11. Immediately thereafter, he returned to work on the Sonnets and completed the following section of 29 sonnets in less than two weeks. Throughout the Sonnets, Wera is frequently referenced, both directly by name and indirectly in allusions to a "dancer" and the mythical Eurydice.[44] Although Rilke claimed that the entire cycle was inspired by Wera, she appears as a character in only one of the poems. He insisted, however, that "Wera's own figure ... nevertheless governs and moves the course of the whole."[45]

The sonnets' contents are, as is typical of Rilke, highly metaphorical. The character of Orpheus (whom Rilke refers to as the "god with the lyre"[46]) appears several times in the cycle, as do other mythical characters such as Daphne. There are also biblical allusions, including a reference to Esau. Other themes involve animals, peoples of different cultures, and time and death.

Letters to a Young Poet

In 1929 a minor writer, Franz Xaver Kappus (1883–1966), published a collection of ten letters that Rilke had written to him when Kappus was a 19-year-old officer cadet studying at the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt. The young Kappus wrote to Rilke, who had also attended the academy, between 1902 and 1908 when he was uncertain about his future career as a military officer or as a poet. Initially he sought Rilke's advice as to the quality of his poetry and whether he ought to pursue writing as a career. While he declined to comment on Kappus's writings, Rilke advised Kappus on how a poet should feel, love and seek truth in trying to understand and experience the world around him and engage the world of art. These letters offer insight into the ideas and themes that appear in Rilke's poetry and his working process and were written during a key period of Rilke's early artistic development after his reputation as a poet began to be established with the publication of parts of Das Stunden-Buch (The Book of Hours) and Das Buch der Bilder (The Book of Images).[47]

Literary style

Figures from Greek mythology (such as Apollo, Hermes and Orpheus) recur as motifs in his poems and are depicted in original interpretations (e.g. in the poem Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes, Rilke's Eurydice, numbed and dazed by death, does not recognize her lover Orpheus, who descended to hell to recover her). Other recurring figures in Rilke's poems are angels, roses, a poet's character and his creative work.

Rilke often worked with metaphors, metonymy and contradictions. For example, in his epitaph, the rose is a symbol of sleep (rose petals are reminiscent of closed eyelids).

Rilke's little-known 1898 poem, "Visions of Christ" depicted Mary Magdalene as the mother of Jesus' child.[48][49] Quoting Susan Haskins: "But it was his [Rilke's] explicit belief that Christ was not divine, was entirely human, and deified only on Calvary, expressed in an unpublished poem of 1893, and referred to in other poems of the same period, which allowed him to portray Christ's love for Mary Magdalen, though remarkable, as entirely human."[49]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

Rilke is one of the more popular, best-selling poets in the United States.[8] In popular culture, Rilke is frequently quoted or referenced in television programs, motion pictures, music and other works when these works discuss the subject of love or angels.[50] His work is often described as "mystical" and has been seized by the New Age community and self-help books.[4] Rilke has been reinterpreted "as a master who can lead us to a more fulfilled and less anxious life".[5][51]

Rilke's work (specifically the Duino Elegies) has deeply influenced several poets and writers, including William H. Gass,[52] Galway Kinnell,[53] Sidney Keyes,[54][55] Stephen Spender,[38] Robert Bly,[38][56] W. S. Merwin,[57] John Ashbery,[58] novelist Thomas Pynchon[59] and philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein[60] and Hans-Georg Gadamer.[61][62] British poet W. H. Auden (1907–1973) has been described as "Rilke's most influential English disciple" and he frequently "paid homage to him" or used the imagery of angels in his work.[63]

Works

Complete works

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sämtliche Werke in 12 Bänden (Complete Works in 12 Volumes), published by Rilke Archive in association with Ruth Sieber-Rilke, edited by Ernst Zinn. Frankfurt am Main (1976)

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Werke (Works). Annotated edition in four volumes with supplementary fifth volume, published by Manfred Engel, Ulrich Fülleborn, Dorothea Lauterbach, Horst Nalewski and August Stahl. Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig (1996 and 2003)

Volumes of poetry

- Leben und Lieder (Life and Songs) (1894)

- Larenopfer (Lares' Sacrifice) (1895)

- Traumgekrönt (Dream-Crowned) (1897)

- Advent (Advent) (1898)

- Das Stunden-Buch (The Book of Hours)

- Das Buch vom mönchischen Leben (The Book of Monastic Life) (1899)

- Das Buch von der Pilgerschaft (The Book of Pilgrimage) (1901)

- Geldbaum (1901)

- Das Buch von der Armut und vom Tode (The Book of Poverty and Death) (1903)

- Das Buch der Bilder (The Book of Images) (4 parts, 1902–1906)

- Neue Gedichte (New Poems) (1907)

- Duineser Elegien (Duino Elegies) (1922)

- Sonette an Orpheus (Sonnets to Orpheus) (1922)

Prose collections

- Geschichten vom Lieben Gott (Stories of God) (Collection of tales, 1900)

- Auguste Rodin (1903)

- Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke (The Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christoph Rilke) (Lyric story, 1906)

- Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge) (Novel, 1910)

Letters

Collected letters

- Gesammelte Briefe in sechs Bänden (Collected Letters in Six Volumes), published by Ruth Sieber-Rilke and Carl Sieber. Leipzig (1936–1939)

- Briefe (Letters), published by the Rilke Archive in Weimar. Two volumes, Wiesbaden (1950, reprinted 1987 in single volume).

- Briefe in Zwei Bänden (Letters in Two Volumes) (Horst Nalewski, Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1991)

Other volumes of letters

- Briefe an Auguste Rodin (Insel Verlag, 1928)

- Briefwechsel mit Marie von Thurn und Taxis, two volumes, edited by Ernst Zinn with a foreword by Rudolf Kassner (Editions Max Niehans, 1954)

- Briefwechsel mit Thankmar von Münchhausen 1913 bis 1925 (Suhrkamp Insel Verlag, 2004)

- Briefwechsel mit Rolf von Ungern-Sternberg und weitere Dokumente zur Übertragung der Stances von Jean Moréas (Suhrkamp Insel Verlag, 2002)

- The Dark Interval – Letters for the Grieving Heart, edited and translated by Ulrich C. Baer (New York: Random House, 2018).

See also

- Baladine Klossowska

- Rainer Maria Rilke Foundation in Sierre, Switzerland

Notes

- From the mid-16th century until the early 20th century, young boys in the Western world were unbreeched and wore gowns or dresses until an age that varied between two and eight.[12]

References

- Biography: Rainer Maria Rilke 1875–1926, Poetry Foundation website. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- See Müller, Hans Rudolf. Rainer Maria Rilke als Mystiker: Bekenntnis und Lebensdeutung in Rilkes Dichtungen (Berlin: Furche 1935). See also Stanley, Patricia H. "Rilke's Duino Elegies: An Alternative Approach to the Study of Mysticism" in Heep, Hartmut (editor). Unreading Rilke: Unorthodox Approaches to a Cultural Myth (New York: Peter Lang 2000).

- Freedman 1998, p. 515.

- Komar, Kathleen L. "Rilke: Metaphysics in a New Age" in Bauschinger, Sigrid and Cocalis, Susan. Rilke-Rezeptionen: Rilke Reconsidered (Tübingen/Basel: Franke, 1995), pp. 155–169. Rilke reinterpreted "as a master who can lead us to a more fulfilled and less anxious life".

- Komar, Kathleen L. "Rethinking Rilke's Duisiner Elegien at the End of the Millennium" in Metzger, Erika A. A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2004), pp. 188–189.

- See also: Mood, John. Rilke on Love and Other Difficulties (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1975); and a book released by Rilke’s own publisher Insel Verlag, Hauschild, Vera (ed.), Rilke für Gestreßte (Frankfurt am Main: Insel-Verlag, 1998).

- Komar, Kathleen L. "Rethinking Rilke's Duisiner Elegien at the End of the Millennium" in Metzger, Erika A., A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2004), 189.

- Komar, Kathleen L. "Rilke in America: A Poet Re-Created" in Heep, Hartmut (editor). Unreading Rilke: Unorthodox Approaches to a Cultural Myth (New York: Peter Lang, 2000), pp. 155–178.

- Prater 1986, p. 5.

- Freedman 1998, p. 9.

- "Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke" at www.washingtonpost.com

- "Boy's Dress", V&A Museum of childhood, accessed June 27, 2019

- Freedman 1998, p. 36.

- "Rainer Maria Rilke | Austrian-German poet". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- Arana, R. Victoria (2008). The Facts on File Companion to World Poetry: 1900 to the Present. Infobase. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-8160-6457-1.

- Anna A. Tavis. Rilke's Russia: A Cultural Encounter. Northwestern University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8101-1466-6. p. 1.

- Rilke, Rainer Maria (2000-07-12). "Rainer Maria Rilke". Rainer Maria Rilke. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- "Mit Rilke in Ronda" by Volker Mauersberger, Die Zeit, 11 February 1983 (in German)

- "Hotel Catalonia Reina Victoria", andalucia.com

- Fatima Naqvi-Peters. A Turning Point in Rilke's Evolution: The Experience of El Greco. The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory, Vol. 72, Is. 4, pp. 344-362, 1997.

- "An Kurt Wolf, 28. März 1917." S. Stefan Schank: Rainer Maria Rilke. pp. 119–121.

- Freedman 1998, p. 505.

- R. M. Rilke: Music as Metaphor

- "Photo and description". Picture-poems.com. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Rainer Maria Rilke: a brief biographical overview". Picture-poems.com. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Katrin Maria Kohl; Ritchie Robertson (2006). A History of Austrian Literature 1918-2000. Camden House. pp. 130ff. ISBN 978-1-57113-276-5.

- Karen Leeder; Robert Vilain (21 January 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Rilke. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24ff. ISBN 978-0-521-87943-9.

- Rainer Maria Rilke; Robert Vilain; Susan Ranson (14 April 2011). Selected Poems: With Parallel German Text. OUP Oxford. pp. 343ff. ISBN 978-0-19-956941-0.

- Erika Mitterer (2004). The prince of darkness. Ariadne Press. p. 663. ISBN 978-1-57241-134-0.

- Freedman 1998, pp. 419–420.

- Freedman 1998, pp. 421–422.

- Freedman 1998, p. 422

- "Rilke-Briefe: Nirgends ein Führer" (in German), Der Spiegel (21/1957). 22 May 1957. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "Elegien gegen die Angstträume des Alltags" by Hellmuth Karasek (in German). Der Spiegel (47/1981). 11 November 1981; Karasek calls Rilke a friend of the Fascists.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Lettres Milanaises 1921–1926. Edited by Renée Lang. Paris: Librairie Plon, 1956

- Excerpt from "Reading Rilke – Reflections on the Problems of Translation" by William H. Gass (1999) ISBN 0-375-40312-4; featured in The New York Times 2000. Accessed 18 August 2010 (subscription required)

- Hoeniger, F. David. "Symbolism and Pattern in Rilke's Duino Elegies" in German Life and Letters, Volume 3, Issue 4 (July 1950), pp. 271–283.

- Perloff, Marjorie, "Reading Gass Reading Rilke" in Parnassus: Poetry in Review, Volume 25, Number 1/2 (2001).

- Gass, William H. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999).

- Rilke, Rainer Maria. "First Elegy" from Duino Elegies, line 1.

- Rilke, Rainer Maria. "First Elegy" from Duino Elegies, line 6; "Second Elegy", line 1.

- Dash, Bibhudutt. "In the Matrix of the Divine: Approaches to Godhead in Rilke's Duino Elegies and Tennyson's In Memoriam" in Language in India Volume 11 (11 November 2011), pp. 355–371.

- Freedman 1998, p. 481.

- Sword, Helen. Engendering Inspiration: Visionary Strategies in Rilke, Lawrence, and H.D. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1995), pp. 68–70.

- Letter to Gertrud Ouckama Knoop, dated 20 April 1923; quoted in Snow, Edward, trans. and ed., Sonnets to Orpheus by Rainer Maria Rilke, bilingual edition, New York: North Point Press, 2004.

- Sonette an Orpheus, Erste Teil, XIX, v. 8: "Gott mit der Leier"

- Freedman, Ralph. "Das Stunden-Buch and Das Buch der Bilder: Harbingers of Rilke's Maturity" in Metzger, Erika A. and Metzger, Michael M. (editors). A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke. (Rochester, New York: Camden House Publishing, 2001), 90–92.

- Liza Knapp, "Tsvetaeva's Marine Mary Magdalene" (The Slavic and East European Journal, Volume 43, Number 4; Winter, 1999).

- Haskins, Susan (1993). Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor. Harcourt. p. 361. ISBN 9780151577651.

- Komar, Kathleen L. "Rethinking Rilke's Duisiner Elegien at the End of the Millennium" in Metzger, Erika A. A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2004), p. 189.

- See also: Mood, John. Rilke on Love and Other Difficulties (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975); and a book released by Rilke’s own publisher Insel Verlag, Hauschild, Vera (editor). Rilke für Gestreßte (Frankfurt am Main: Insel-Verlag, 1998).

- http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/3576/the-art-of-fiction-no-65-william-gass

- Malecka, Katarzyna. Death in the Works of Galway Kinnell (Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2008), passim.

- Guenther, John. Sidney Keyes: A Biographical Enquiry (London: London Magazine Editions, 1967), p. 153.

- "Self-Elegy: Keith Douglas and Sidney Keyes" (Chapter 9) in Kendall, Tim. Modern English War Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Metzger, Erika A. and Metzger, Michael M. "Introduction" in A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2004), p. 8.

- Perloff, Marjorie. "Apocalypse Then: Merwin and the Sorrows of Literary History" in Nelson, Cary and Folsom, Ed (eds). W. S. Merwin: Essays on the Poetry (University of Illinois, 1987), p. 144.

- Perloff, Marjorie. "Transparent Selves': The Poetry of John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara," in Yearbook of English Studies: American Literature Special Number 8 (1978):171–196, at p. 175.

- Robey, Christopher J. The Rainbow Bridge: On Pynchon's Use of Wittgenstein and Rilke (Olean, New York: St. Bonaventure University, 1982).

- Perloff, Marjorie. Wittgenstein's Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), passim. which points towards Wittgenstein's generous financial gifts to Rilke among several Austrian artists, although he prefer Rilke's earlier works and was distressed by his post-war writings.

- Gadamer analyzed many of Rilke's themes and symbols. See: Gadamer, Hans-Georg. "Mythopoietische Umkehrung im Rilke's Duisener Elegien" in Gesammelten Werke, Band 9: Ästhetik und Poetik II Hermenutik im Vollzug (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1993), pp. 289–305.

- Dworick, Stephanie. In the Company of Rilke: Why a 20th-Century Visionary Poet Speaks So Eloquently to 21st-Century Readers (New York: Penguin, 2011).

- Cohn, Stephen (translator). "Introduction" in Rilke, Rainer Maria. Duino Elegies: A Bilingual Edition (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1989), pp. 17–18. Quote: "Auden, Rilke's most influential English disciple, frequently paid homage to him, as in these lines which tell of the Elegies and of their difficult and chancy genesis..."

Sources

- Freedman, Ralph (1998). Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke. New York: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-810-11543-9.

- Prater, Donald A. (1986). A Ringing Glass: The Life of Rainer Maria Rilke. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Further reading

Biographies

- Corbett, Rachel, You Must Change Your Life: the Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin, New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2016.

- Tapper, Mirjam, Resa med Rilke, Mita bokförlag.

- Torgersen, Eric, Dear Friend: Rainer Maria Rilke and Paula Modersohn-Becker, Northwestern University Press, 1998.

- Von Thurn und Taxis, Princess Marie, The Poet and The Princess: Memories of Rainer Maria Rilke, Amun Press, 2017

Critical studies

- Engel, Manfred and Lauterbach, Dorothea (ed.), Rilke Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung, Stuttgart: Metzler, 2004.

- Erika, A and Metzger, Michael, A Companion to the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke, Rochester, 2001.

- Gass, William H. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

- Goldsmith, Ulrich, ed., Rainer Maria Rilke, a verse concordance to his complete lyrical poetry. Leeds: W. S. Maney, 1980.

- Hutchinson, Ben. Rilke's Poetics of Becoming, Oxford: Legenda, 2006.

- Leeder, Karen, and Robert Vilain (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Rilke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-70508-0

- Mood, John, A New Reading of Rilke's 'Elegies': Affirming the Unity of 'life-and-death Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7734-3864-4.

- Numerous contributors, A Reconsideration of Rainer Maria Rilke, Agenda poetry magazine, vol. 42 nos. 3–4, 2007. ISBN 978-0-902400-83-2.

- Pechota Vuilleumier, Cornelia, Heim und Unheimlichkeit bei Rainer Maria Rilke und Lou Andreas-Salomé. Literarische Wechselwirkungen. Olms, Hildesheim, 2010. ISBN 978-3-487-14252-4

- Ryan, Judith. Rilke, Modernism, and Poetic Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Schwarz, Egon, Poetry and Politics in the Works of Rainer Maria Rilke. Frederick Ungar, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8044-2811-8.

- Neuman, Claude, The Sonnets to Orpheus and Selected Poems, English and French rhymed and metered translations, trilingual German-English-French editions, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2017, 2018

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rainer Maria Rilke |

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Rainer Maria Rilke |

Media related to Rainer Maria Rilke at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rainer Maria Rilke at Wikimedia Commons- Rainer Maria Rilke: Letters to a Young Poet, The first letter. (full text in: EN FR IT DE ES CH)

- Rainer Rilke and his Poem Black Cat

- Works by Rainer Maria Rilke at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Rainer Maria Rilke at Internet Archive

- Works by Rainer Maria Rilke at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Publications by and about Rainer Maria Rilke in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- "Literary estate of Rainer Maria Rilke". HelveticArchives. Swiss National Library.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Profile at Poets.org

- International Rilke Society (in German)

- Rilke, Rainer Maria (1920). Erste Gedichte. Leipzig: Insel.

- Translator of Rilke into English, interview with Joanna Macy (2010 original, 2019 updated: transcript and audio) for OnBeing.org

- Poems by Rainer Maria Rilke: a new translation A new translation by Timothy Watson published on February 28, 2018