The Year My Voice Broke

The Year My Voice Broke is a 1987 Australian coming of age drama film written and directed by John Duigan and starring Noah Taylor, Loene Carmen and Ben Mendelsohn. Set in 1962 in the rural Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, it was the first in a projected trilogy of films centred on the experiences of an awkward Australian boy, based on the childhood of writer/director John Duigan. The film itself is a series of interconnected segments narrated by Danny who recollects how he and Freya grew apart over the course of one year. Although the trilogy never came to fruition, it was followed by a 1991 sequel, Flirting. The film was the recipient of the 1987 Australian Film Institute Award for Best Film, a prize which Flirting also won in 1990.

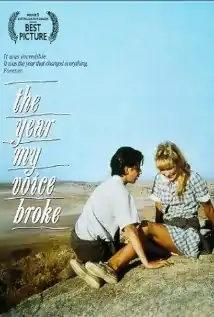

| The Year My Voice Broke | |

|---|---|

Video release artwork | |

| Directed by | John Duigan |

| Produced by | Terry Hayes George Miller Doug Mitchell |

| Written by | John Duigan |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Geoff Burton |

| Edited by | Neil Thumpston |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Hoyts Distribution Avenue Pictures (U.S.) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $850,000[1] |

| Box office | A$1,513,000 (Australia) |

Plot

In the 1960s, Danny, a thin, socially awkward adolescent, falls in love with his best friend Freya in rural New South Wales, Australia. Unfortunately for him, she is attracted to Trevor, a high school rugby star, larrikin and petty criminal who helps Danny with the school bullies. Shortly after sleeping with Freya at the abandoned house, Trevor steals a car for a joyride and is arrested and sent to juvenile detention; it is while he is away that Freya reveals to Danny that she is pregnant. Danny offers to marry her and claim that the child is his, but Freya refuses, saying that she does not want to marry anyone. Meanwhile, intrigued by a locket left to Freya by an elderly friend of theirs who recently died—engraved "SEA"—Danny begins to investigate the town's past, and discovers a lone cross in the cemetery bearing those initials, belonging to a "Sara Elizabeth Amery", who died days after Freya was born. Through inquiries with his parents, Danny learns that Sara was well known for her sexual promiscuity years ago, and that she was Freya's biological mother, who died trying to give birth by herself at the abandoned house.

Meanwhile, Trevor breaks out of detention, steals another car, and severely wounds a store clerk during an armed robbery. Trevor returns to town long enough to reunite with Freya at the abandoned house, and learn that she is pregnant. The police arrive at Trevor's hiding place, but Danny warns him, and Trevor is able to escape. The police then run his car off the road during the course of the pursuit, and Trevor dies the next day. Freya disappears, and later suffers a miscarriage and hypothermia until Danny finds her (at the abandoned house) and takes her to the hospital. Hesitantly, Danny reveals the identity of Freya's mother to her. Realising the stigma now hanging over her, Freya decides to leave on the night train for the city. At the station, Danny gives her his life's savings to support herself and sees her off—promising their friendship to one another and to keep in touch. Later, Danny travels to their favourite hangout spot and carves Freya's, Trevor's and his name into a rock, as his adult self informs the audience that he never saw Freya again.

Cast

- Noah Taylor as Danny Embling

- Loene Carmen as Freya Olson

- Ben Mendelsohn as Trevor Leishman

- Graeme Blundell as Nils Olson

- Lynette Curran as Anne Olson

- Malcolm Robertson as Bruce Embling

- Judi Farr as Sheila Embling

Production

John Duigan wrote a script based on his experiences going to a boarding school in the mid-1960s called Flirting. He was unable to get the film funded so wrote a prequel, The Year My Voice Broke, based on the leading character growing up in a country town. Duigan had worked with Kennedy Miller making the miniseries Vietnam and they agreed to make the film as one of four telemovies they were making for the Channel Ten network. Duigan was allowed to make the film on 35 mm.[2][3] The film was shot, but not set, in Braidwood, New South Wales. It had several working titles, including Reflections of a Golden Childhood and Museum of Desire.

Music

The main theme used in the film is "The Lark Ascending" by English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. At a 2005 special-event screening in Sydney, director John Duigan stated that he chose the piece as he felt it complemented Danny's adolescent yearning. Additional source music featured in the film includes:[4]

- "Apache", performed by The Shadows

- "Corinna Corinna", performed by Ray Peterson

- "Temptation", performed by The Everly Brothers

- "Tower of Strength" and "A Hundred Pounds of Clay", performed by Gene McDaniels

- "Diana", performed by Paul Anka

- "(The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance", performed by Gene Pitney

- "Get a Little Dirt on Your Hands", performed by The Delltones

- "I Remember You", performed by Frank Ifield

- "That's the Way Boys Are", performed by Lesley Gore

All of the songs are to period, except "That's the Way Boys Are", which was released in 1964.

Release

The Year My Voice Broke grossed $1,513,000 at the box office in Australia,[5] which is equivalent to $3,041,130 in 2009 dollars. The U.S. box office was $213,901.[6] The movie was entered in the AFI Awards, despite protests that it was a telemovie. However, it was allowed in because Duigan argued it was shot in 35 mm and designed as a feature. The movie won five AFI Awards, which led to Hoyts picking it up and releasing it as a feature film.[2]

Home media

In America, the film was first released on VHS in 1988 by International Video Entertainment. It was later re-released digitally in 2015 by its successor, Lionsgate. A 21st-anniversary special-edition DVD was released in December 2008. Special features include an introduction by George Miller and a 50-minute retrospective, with Duigan interviewing Loene Carmen and Ben Mendelsohn in Australia and Noah Taylor in England.

Awards

The film received the following 1987 AFI Awards:[7]

- Best Film (Terry Hayes, Doug Mitchell, George Miller)

- Best Direction (John Duigan)

- Best Original Screenplay (John Duigan)

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Ben Mendelsohn)

- Members Prize

The film was also nominated for the following 1987 AFI Awards:

- Best Actor in a lead role (Noah Taylor)

- Best Actress in a lead role (Loene Carmen)

- Best Achievement in Editing (Neil Thumpston)

In commenting about the film, the AFI website states:[7]

The most important awards [of 1987] went to The Year My Voice Broke. It won Best Film for producer George Miller who had twice been named Best Director (for the two Mad Max films). John Duigan won the awards for direction and original screenplay. He had had two previous nominations for direction (Mouth to Mouth and Winter of Our Dreams) and two for original screenplay (The Trespassers and Winter of Our Dreams). Ben Mendelsohn was named Best Supporting Actor.

References

- "Wednesday magazine Braidwood's film nominated for 7 AFI awards". The Canberra Times. 62 (18, 995). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 7 October 1987. p. 25. Retrieved 28 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- Stratton, David (1990). The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry. Pan MacMillan. pp. 348–350. ISBN 0-7329-0250-9.

- Murray, Scott (November 1989). "John Duigan: Awakening the Dormant". Cinema Papers: 31–35, 77.

- The Year My Voice Broke (1987), retrieved 4 January 2018

- Film Victoria - Australian Films at the Australian Box Office Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- General Film Information - The Year My Voice Broke Archived 11 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- The Year My Voice Broke at IMDb

- The Year My Voice Broke at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Year My Voice Broke at Box Office Mojo

- The Year My Voice Broke at Oz Movies

- The Year My Voice Broke at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Hinson, Hal (12 September 1988). "The Year My Voice Broke (PG-13)". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "Review and Critical Uptake - The Year My Voice Broke". Archived from the original on 27 July 2001.

- Gibson, Suzie (8 June 2017). "Where are the epic women's coming of age screen stories?". The Conversation.