Third voyage of James Cook

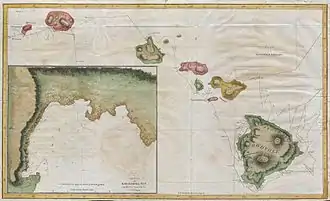

James Cook's third and final voyage (12 July 1776 – 4 October 1780) took the route from Plymouth via Cape Town and Tenerife to New Zealand and the Hawaiian Islands, and along the North American coast to the Bering Strait.

Its ostensible purpose was to return Omai, a young man from Raiatea, to his homeland, but the Admiralty used this as a cover for their plan to send Cook on a voyage to discover the Northwest Passage. HMS Resolution, to be commanded by Cook, and HMS Discovery, commanded by Charles Clerke, were prepared for the voyage which started from Plymouth in 1776.

Omai was returned to his homeland and the ships sailed onwards, encountering the Hawaiian Archipelago, before reaching the Pacific coast of North America. The two charted the west coast of the continent and passed through the Bering Strait when they were stopped by ice from sailing either east or west. The vessels returned to the Pacific and called briefly at the Aleutians before retiring towards Hawaii for the winter.

At Kealakekua Bay, a number of quarrels broke out between the Europeans and Hawaiians culminating in Cook's death in a violent exchange on 14 February 1779. The command of the expedition was assumed by Charles Clerke who tried in vain to find the passage before his own death. Under the command of John Gore the crews returned to a subdued welcome in London in October 1780.

Conception

Principally, the purpose of the voyage was an attempt to discover the famed Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific around the top of North America. Cook's orders from the Admiralty were driven by a 1745 Act which, when extended in 1775, promised a £20,000 prize for whoever discovered the passage.[1] Initially the Admiralty had wanted Charles Clerke to lead the expedition, with Cook, who was in retirement following his exploits in the Pacific, acting as a consultant.[2] However, Cook had researched Bering's expeditions, and the Admiralty ultimately placed their faith in the veteran explorer to lead with Clerke accompanying him. The arrangement was to make a two pronged attack, Cook moving from the Bering Strait in the north Pacific with Richard Pickersgill in the frigate Lyon taking the Atlantic approach. They planned to rendezvous in the summer of 1778.

In August 1773 Omai, a young Ra'iatean man, embarked from Huahine, travelling to Europe on Adventure, commanded by Tobias Furneaux who had touched at Tahiti as part of James Cook's second voyage of discovery in the Pacific. He arrived in London in October 1774 and was introduced into society by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks and became a favourite curiosity in London. Ostensibly, the third voyage was planned to return Omai to Tahiti; this is what the general public believed.

Preparation and personnel

Vessels and provisions

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS Resolution. Resolution began her career as the 462 ton North Sea collier Marquis of Granby, launched at Whitby in 1770, and purchased by the Royal Navy in 1771 for £4,151 and converted at a cost of £6,565. She was 111 feet (34 m) long and 35 feet (11 m) abeam. She was originally registered as HMS Drake. After she returned to Britain in 1775 she had been paid off but was then recommissioned in February 1776 for Cook's third voyage. The vessel had on board a quantity of livestock sent by George III as gifts for the South Sea Islanders. These included sheep, cattle, goats and pigs as well as the more usual poultry.[3] Cook also requisitioned: "100 kersey jackets, 60 kersey waistcoats, 40 pairs of kersey breeches, 120 linsey waistcoats, 140 linsey drawers, 440 checkt shirts, 100 pair checkt draws, 400 frocks, 700 pairs of trowsers, 500 pairs of stockings, 80 worsted caps, 340 Dutch caps and 800 pairs of shoes."[4]

Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery,[5] which was a Whitby-built collier of 299 tons, originally named Diligence when she was built in 1774 by G. & N. Langborn for Mr. William Herbert from whom she was bought by the Admiralty. She was 27 feet (8.2 m) abeam with a hold depth of 11 feet (3.4 m). She cost £2,415 including alterations. Originally a brig, Cook had her changed to a full-rigged ship.[6]

Ships' companies

As his first lieutenant, Cook had John Gore, who had been round the world with him in the Endeavour and with Samuel Wallis in HMS Dolphin. James King was his second officer and John Williamson third. The master was William Bligh, who would later command HMS Bounty. William Anderson was surgeon and also acted as botanist, and the painter John Webber was the official artist. The crew included six midshipmen, a cook and a cook's mate, six quartermasters, twenty marines including a lieutenant, and forty-five able seamen.[3]

Discovery was commanded by Charles Clerke, who had previously served on Cook's first two expeditions and had previously sailed with Byron. His first lieutenant was James Burney, his second John Rickman and among the midshipmen was George Vancouver. She had a crew of 70: 3 officers, 55 crew, 11 marines and one civilian.[3]

Other crew members included:

- William Bayly served as astronomer

- James Cleveley, brother of artists John and Robert, served as carpenter

- George Dixon served on Resolution as armourer[7]

- John Ledyard, an American who served as a marine

- David Nelson was a botanical collector[8]

- Omai, a native of the island of Raiatea who had been brought to London on Cook's second voyage, acted as interpreter until he returned home

- Nathaniel Portlock served as master's mate on Discovery and later Resolution

- Edward Riou was a midshipman on Discovery and later Resolution

- Henry Roberts served as master's mate on Resolution. He prepared the charts for the official account of the voyage.[9][10]

- David Samwell was surgeon's 1st mate on Resolution

- William Taylor, midshipman on Resolution

- James Trevenen, midshipman on Resolution

- John Watts, midshipman on Resolution

Voyage

Captain James Cook sailed from Plymouth on 12 July 1776. Clerke in the Discovery was delayed in London and did not follow until 1 August. On the way to Cape Town the Resolution stopped at Tenerife to top up on supplies. The ship reached Cape Town on 17 October and Cook immediately had it re-caulked because it had been leaking very badly, especially through the main deck. When the Discovery arrived on 10 November she was also found to be in need of re-caulking.

.jpg.webp)

The two ships sailed in company on 1 December and on 13 December located and named the Prince Edward Islands. Twelve days later he found the Kerguelen Islands which he had failed to find on his second voyage. Driven by strong westerly winds they reached Van Diemen's Land on 26 January 1777 where they took on water and wood and became cursorily acquainted with the aborigines living there. The ships sailed on, arriving at Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand on 12 February. Here the Māori were apprehensive because they believed that Cook would take revenge for the deaths in December 1773 of ten men from the Adventure, commanded by Furneaux, on his second voyage. After two weeks the ships left for Tahiti but contrary winds carried them westwards to Mangaia where land was first sighted on 29 March. In order to re-provision, the ships went with the westerly winds to the Friendly Isles (now known as Tonga) stopping en route at Palmerston Island. They stayed in the Friendly Isles from 28 April until mid July when they set out for Tahiti, arriving on 12 August.

After returning Omai, Cook delayed his onward journey until 7 December when he travelled north and on 18 January 1778 became the first European to visit the Hawaiian Islands. In passing and after initial landfall at Waimea harbour, Kauai, Cook named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich—the acting First Lord of the Admiralty.[11] They observed that the inhabitants spoke a version of the Polynesian language familiar to them from their previous travels in the South Pacific.

From Hawaii, he went northeast on 2 February to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California. He made landfall on 6 March at approximately 44°30′ north latitude, near Cape Foulweather on the Oregon coast, which he named. Bad weather forced his ships south to about 43° north before they could begin their exploration of the coast northward.[12] He unknowingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca and soon after entered Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. He anchored near the First Nations village of Yuquot. Cook's two ships spent about a month in Nootka Sound, from 29 March to 26 April 1778, in what Cook called Ship Cove, now Resolution Cove,[13] at the south end of Bligh Island, about 5 miles (8 km) east across Nootka Sound from Yuquot, a Nuu-chah-nulth village (whose chief Cook did not identify but may have been Maquinna). Relations between Cook's crew and the people of Yuquot were cordial if sometimes strained. In trading, the people of Yuquot demanded much more valuable items than the usual trinkets that had worked for Cook's crew in Hawaii. Metal objects were much desired, but the lead, pewter, and tin traded at first soon fell into disrepute. The most valuable items the British received in trade were sea otter pelts. Over the month-long stay the Yuquot "hosts" essentially controlled the trade with the British vessels, instead of vice versa. Generally the natives visited the British vessels at Resolution Cove instead of the British visiting the village of Yuquot at Friendly Cove.[14]

After leaving Nootka Sound, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait, on the way identifying what came to be known as Cook Inlet in Alaska. It has been said that, in a single visit, Cook charted the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska and closed the gaps in Russian (from the west) and Spanish (from the south) exploratory probes of the northern limits of the Pacific.[15]

The Bering Strait proved to be impassable, although he made several attempts to sail through it. He became increasingly frustrated on this voyage, and perhaps began to suffer from a stomach ailment; it has been speculated that this led to irrational behaviour towards his crew, such as forcing them to eat walrus meat, which they found inedible.[16] From the Bering Strait the crews went south to Unalaska in the Aleutians where Cook put in on 2 October to again re-caulk the ship's leaking timbers. During a three-week stay they met Russian traders and got to know the native population. The vessels left for the Sandwich Islands on 24 October, sighting Maui on 26 November 1778.

The two vessels sailed around the Hawaiian Archipelago for some eight weeks looking for a suitable anchorage, until they made landfall at Kealakekua Bay, on 'Hawaii Island', the largest island in the group, on 17 January 1779. During their navigation around the islands the ships were accompanied by large numbers of gift laden canoes whose occupants came fearlessly aboard the vessels. Palea, a chief, and Koa'a, a priest came aboard and ceremoniously escorted Cook ashore where he was put through a long and peculiar ceremony before being allowed back to the ship.[17] Unbeknown to Cook, his arrival coincided with the Makahiki, a Hawaiian harvest festival of worship for the Polynesian god Lono. Coincidentally, the form of Cook's ship, HMS Resolution, or more particularly the mast formation, sails and rigging, resembled certain significant artefacts that formed part of the season of worship.[16][18] Similarly, Cook's clockwise route around the island of Hawaii before making landfall resembled the processions that took place in a clockwise direction around the island during the Lono festivals. It has been argued that such coincidences were the reasons for Cook's (and to a limited extent, his crew's) initial deification by some Hawaiians who treated Cook as an incarnation of Lono.[19] Though this view was first suggested by members of Cook's expedition, the idea that any Hawaiians understood Cook to be Lono, and the evidence presented in support of it has been challenged.[16][20]

Death

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, the foremast of the Resolution broke and the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay for repairs.[21] It has been hypothesised that the return to the islands by Cook's expedition was not just unexpected by the Hawaiians, but also unwelcome because the season of Lono had recently ended (presuming that they associated Cook with Lono and Makahiki). In any case, tensions rose and a number of quarrels broke out between the Europeans and Hawaiians. On 14 February at Kealakekua Bay, some Hawaiians took one of Cook's small boats. Normally, as thefts were quite common in Tahiti and the other islands, Cook would have taken hostages until the stolen articles were returned.[22]

Indeed, he attempted to take hostage the King of Hawaiʻi, Kalaniʻōpuʻu. The Hawaiians prevented this when they spotted Cook luring King Kalaniʻōpuʻu to his ship on a false pretext and sounded the alarm. Kalaniʻōpuʻu himself eventually realized Cook's real intentions and suddenly stopped and sat where he stood. Before Cook could force the king back up, hundreds of native Hawaiians, some armed with weapons, appeared and began an angry pursuit, and Cook's men had to retreat to the beach. As Cook turned his back to help launch the boats, he was struck on the head by the villagers and then stabbed to death as he fell on his face in the surf.[23] Hawaiian tradition says he was killed by a chief named Kalanimanokahoowaha.[24] The Hawaiians dragged his body away. Four marines, Corporal James Thomas, Private Theophilus Hinks, Private Thomas Fatchett and Private John Allen, were also killed and two others were wounded in the confrontation.[25][26]

The esteem in which he was nevertheless held by the Hawaiians resulted in his body being retained by their chiefs and elders. Following the practice of the time, Cook's body underwent funerary rituals similar to those reserved for the chiefs and highest elders of the society. The body was disembowelled, baked to facilitate removal of the flesh, and the bones were carefully cleaned for preservation as religious icons in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of European saints in the Middle Ages. Some of Cook's remains, disclosing some corroborating evidence to this effect, were eventually returned to the British for a formal burial at sea following an appeal by the crew.[27]

Homeward voyage

Clerke, who was dying of tuberculosis, took over the expedition and sailing north, landed on the Kamchatka peninsula where the Russians helped him with supplies and to make repairs to the ships. He made a final attempt to pass beyond the Bering Strait and died on his return at Petropavlovsk on 22 August 1779. From here the ships' reports were sent overland, reaching London five months later.[28] Following the death of Clerke, Resolution and Discovery turned for home commanded by John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage (and now in command of the expedition), and James King.[29] After passing down the coast of Japan they reached Macao, in China in the first week of December and from there followed the East India trade route via Sunda Strait to Cape Town.[30]

Return home

An Atlantic gale blew the expedition so far north that they first made landfall at Stromness in Orkney. The Resolution and Discovery arrived off Sheerness on 4 October 1780. The news of Cook's and Clerke's deaths had already reached London, so their homecoming was to a subdued welcome.[30]

Publication of journals

Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by James King. Cook's own journal ended abruptly on 17 January 1779, but those of his crew were handed to the Admiralty for editing before publication. In anticipation of the publication of his journal, Cook had spent a lot of shipboard time rewriting it.[31]

The task of editing the account of the voyage was entrusted by the Admiralty to Dr John Douglas, Canon of St Paul's, who had the journals in his possession by November 1780. He added the journal of the surgeon, William Anderson, to the journals of Cook and James King. The final publication, in June 1784, amounted to three volumes, 1,617 pages, with 87 plates. Public interest in the account resulted in its selling out within three days, despite the high price of £4 14s 6d.[32]

As on the earlier voyages, unofficial accounts written by members of the crew were produced. The first to appear, in 1781, was a narrative based on the journal of John Rickman entitled Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage. The German translation Tagebuch einer Entdekkungs Reise nach der Südsee in den Jahren 1776 bis 1780 unter Anführung der Capitains Cook, Clerke, Gore und King by Johann Reinhold Forster appeared in the same year. Heinrich Zimmermann published in 1781 his diary Reise um die Welt mit Capitain Cook. Then in 1782 an account by William Ellis, Surgeon's Mate on the Discovery, was published, followed in 1783 by John Ledyard's A Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage published in Connecticut.[33]

References

- Cook, James. A voyage to the Pacific Ocean. Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty.

- Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 52

- Villiers 1967, p. 196

- "CCSU – 225 Years Ago: Apr – Jun 1776". 2002. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Collingridge 2003, p. 327

- Gibson, Doug (2004). "The Discovery". Captain Cook Society. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Dixon's Voyage Round the World", The Monthly Review, 80: 502–511, June 1789, OCLC 1772616

- St. John, Harold (1976). "Biography of David Nelson, and an account of his botanizing in Hawaii". Pacific Science. 30 (1): 1–5. hdl:10125/1529.

- Cook's Log, page 315, volume 7, number 4 (1984).

- Cook's Log, page 16, volume 31, number 4 (2008).

- Collingridge 2003, p. 380

- Hayes 1999, pp. 42–43

- "Resolution Cove". BC Geographical Names.

- Fisher 1979

- Williams 1997, p. xxvi

- Obeyesekere 1992

- Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 57

- Collingridge 2002, p. 404

- Sahlins 1985

- Obeyesekere 1997

- Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 58

- Collingridge 2002, p. 409

- Collingridge 2003, p. 410

- Sheldon Dibble (1843). History of the Sandwich Islands. Lahainaluna: Press of the Mission Seminary. p. 61.

- "Muster for HMS Resolution during the third Pacific voyage, 1776-1780" (PDF). Captain Cook Society. 15 October 2012. p. 20. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 60

- Collingridge 2003, p. 413

- Collingridge 2003, p. 412

- Collingridge 2003, p. 423

- Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 61

- Williams 2008, p. 52

- Williams 1997, p. xxxii

- Williams 2008, pp. 20–21

Bibliography

- Beaglehole, John Cawte (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. A & C Black. ISBN 0-7136-1382-3.

- Collingridge, Vanessa (February 2003). Captain Cook: The Life, Death and Legacy of History's Greatest Explorer. Ebury Press. ISBN 0-09-188898-0.

- Hayes, Derek (1999). Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and Discovery. Sasquatch Books. ISBN 1-57061-215-3.

- Hough, Richard (1994). Captain James Cook. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-82556-1.

- McLynn, Frank (2011). Captain Cook: Master of the Seas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11421-8.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath (1992). The Apotheosis of Captain Cook: European Mythmaking in the Pacific. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05752-4.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath (1997). The Apotheosis of Captain Cook: European Mythmaking in the Pacific. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05752-1.

With new preface and afterword replying to criticism from Sahlins.

- Rigby, Nigel; van der Merwe, Pieter (2002). Captain Cook in the Pacific. National Maritime Museum, London UK. ISBN 0-948065-43-5.

- Robson, John (2004). The Captain Cook Encyclopædia. Random House Australia. ISBN 0-7593-1011-4.

- Sahlins, Marshall David (1985). Islands of history. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73358-6.

- Sahlins, Marshall David (1995). How "Natives" Think: About Captain Cook, for example. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73368-5.

- Villiers, Alan (1967). Captain Cook. The Seaman's Seaman. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139062-X.

- Williams, Glyndwr (1997). Captain Cook's Voyages: 1768–1779. London: The Folio Society.

- Williams, Glyndwr (2004). Captain Cook: Explorations and Reassessments's. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-100-7.

- Williams, Glyndwr (2008). The Death of Captain Cook. A Hero Made and Unmade. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-842-4.

Further reading

- Edwards, Philip, ed. (2003). James Cook: The Journals. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-043647-2.

Prepared from the original manuscripts by J. C. Beaglehole 1955–67

- Richardson, Brian (2005). Longitude and Empire: How Captain Cook's Voyages Changed the World. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-1190-0.

- Thomas, Nicholas (2003). The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook. New York: Walker & Co. ISBN 0-8027-1412-9.

- Villiers, Alan (Summer 1956–57). "James Cook, Seaman". Quadrant. 1 (1): 7–16.

- Villiers, Alan John (1983) [1903]. Captain James Cook. Newport Beach, CA: Books on Tape.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Third voyage of James Cook. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Captain Cook Society

- Cook's Third Voyage Website of illustrations and maps about Cook's third voyage