Thoronet Abbey

Thoronet Abbey (French: L'abbaye du Thoronet) is a former Cistercian abbey built in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century, now restored as a museum. It is sited between the towns of Draguignan and Brignoles in the Var Department of Provence, in southeast France. It is one of the three Cistercian abbeys in Provence, along with the Sénanque Abbey and Silvacane, that together are known as "the Three Sisters of Provence."

Thoronet Abbey is one of the best examples of the spirit of the Cistercian order. Even the acoustics of the church imposed a certain discipline upon the monks; because of the stone walls, which created a long echo, the monks were forced to sing slowly and perfectly together.

Chronology of Thoronet Abbey

- 1098 - Founding of the first Cistercian monastery at Cîteaux, near Dijon, in Burgundy, by Robert de Molesme.

- 1136 - A group of Cistercian monks from the Abbey of Mazan, a "granddaughter" of the monastery at Citeaux, found a new monastery called Notre-dame-des-Floriéges, in the Var region.

- 1140 - Raimond and Etienne des Baux donate land for a new monastery in a remote mountain valley 45 kilometers northwest of Fréjus.

- about 1157 The monks move from Floriéges to Le Thoronet

- about 1176 to 1200 Construction of the monastery[1]

- 1176 - Alphonse I, the Count of Provence, confirms the Abbey property.

- 1199 - the troubadour Folquet de Marseille becomes Abbot of Le Thoronet.[2]

- 1785 - The Abbey is declared bankrupt and secularized.

- 1791 A sale of Abbey property is announced -

- 1840 Thoronet Abbey is one of the first buildings in France to be classified an historical monument.

- 1841 - Restoration of the monastery begins.

- 1854 - the French Government purchases the cloister and monks quarters.

- 1938 - the rest of the monastery is purchased by the French Government.

History

In 1098 Robert de Molesme founded a "new monastery" at Cîteaux in Burgundy, as a reaction to what he saw as the excessive luxury and decoration of Benedictine monasteries, under the direction of Cluny. He called for a stricter observance of the Rule of St Benedict, written in the 6th century, and a sober aesthetic which emphasized volume, light, and fine masonry, eliminating the distraction of details.[3]

Under Bernard of Clairvaux, the Cistercian Order began a rapid expansion. By the time of his death in 1154, there were 280 Cistercian monasteries in France - by the end of the 12th century, over 500.

The first Cistercian community in Provence had settled at Notre-Dame de Florielle, on the Florieyes river near Tourtour. where they had been given land by the local lords of Castellane. The first site apparently was not satisfactory for their system of agriculture, so in about 1157 they moved twenty-five kilometers south, to land they already owned at Le Thoronet. The new site had the advantages of more fertile lands, several streams and a spring.

It is not known exactly when the monastery was built, but work was probably underway in 1176, when the title to the property was confirmed by the Count of Provence. The entire monastery was built at once, which helps explain its unusual architectural unity. The church was probably built first, at the end of the 12th century, followed by the rest of the monastery in the early 13th century.

The first known abbot of le Thoronet was Folquet de Marseille, elected in 1199. Born about 1150 into a family of Genoese merchants, he had a remarkable career, first as a troubadour, a composer and singer of secular love songs, who was famous throughout medieval Europe. In 1195 he left his musical career and became a monk, then abbot, then, in 1205, the Bishop of Toulouse. Less than a century after his death, Dante honored him by placing him as one of the inhabitants of Paradise, in Paradiso Canto IX.[4]

In the 13th century, there were no more than twenty-five monks in the monastery, but money came in from donations, and the Abbey owned extensive lands between upper Provence and the Mediterranean coast. The most important industry for the monastery was raising cattle and sheep. The meat was sold on the local market, and the skins of sheep were used for making parchment, which was used in the scriptorium of the monastery. The Abbey also operated salt ponds at Hyères, and fisheries on the coast at Martigues, Hyères and Saint-Maxime. Fish that was not required at the Abbey was sold on the local market.

Much of the farming and administration was done by the lay brothers, monks drawn from a lower social class, who shared the monastery with the choir monks, who were educated and often from noble families. The lay brothers did not participate in the choir or in the decisions of the monastery, and slept in a separate building.

By the 14th century, the monastery was in decline. In 1328, the Abbot accused his own monks of trying to rob the local villagers, being only a few years after the Great Famine. In 1348, Provence was devastated again, this time by the Black Plague which further reduced the population. By 1433, there were only four monks living at Le Thoronet.

In the 14th century, the popes at Avignon began the practice of naming outsiders as the abbots of monasteries, held in commendam. In the 15th century, this privilege was taken over by the kings of France, who often chose abbots for financial or political reasons. The new abbots in commendam received a share of the monastery's income, but did not reside there. By the 16th century, while the abbey church was maintained, the other buildings were largely in ruins. The monastery was probably abandoned for a time during the Wars of Religion.

In the 18th century, the abbot decided the order's rules were too strict, and added decorative features, such as statues, a fountain. and an avenue of chestnut trees. The Abbey was deeply in debt, and in 1785, the abbot, who lived in Bourges, declared bankruptcy. Le Thoronet was deconsecrated in 1785, and the seven remaining monks moved to other churches or monasteries. The building was to be sold in 1791, but the state officials in charge of the sale declared that the church, cemetery, fountain and row of chestnut trees were "treasures of art and architecture", which should remain "the Property of the Nation." [5] The rest of the monastery buildings and lands were sold.

In 1840, the ruined buildings came to the attention of Prosper Mérimée, a writer and the first official inspector of monuments. It was entered onto the first list of French Monuments historiques, and restoration of the church and bell tower began in 1841. In 1854 the state bought the cloister, chapter-house, courtyard and dormitory, and in 1938, bought the remaining parts of the monastery still in private ownership.

Since 1978, the members of a religious order, the Sisters of Bethlehem, have been celebrating Sunday Mass in the abbey.

The Abbey buildings

Following the Rule of St. Benedict, Thoronet Abbey was designed to be an autonomous community, taking care of all of its own needs. The monks lived isolated in the center of this community, where access by laymen was strictly forbidden.

The design of the Abbey was an expression of the religious beliefs of the Cistercians. It used the most basic and pure elements; rock, light, and water, to create an austere, pure and simple world for the monks who inhabited it. The placement of the church literally atop a rock symbolized the precept of building upon strong faith. The simplicity of the design was supposed to inspire a simple life, and the avoidance of distractions.

The Abbey was constructed of plainly-cut stones taken from a quarry close by. All the stones were the same kind and colour and matched the stony ground around the church, giving a harmony to the ensemble. The stones were carefully cut and placed to provide smooth ashlar surfaces, to avoid any flaws or visual distractions.

The water supply was a crucial factor for the Cistercian monks; it was used for drinking and cooking, for powering the mill, and for religious ceremonies, such as the mandatum, which took place once a week. The monks devised an ingenious water system, which probably provided running water in the kitchen and for the fountains where the monks washed, as well as pure water for religious ceremonies.

The Abbey Church

The Abbey church is placed on the highest point of the site, and is in the form of a Latin cross, about forty metres long and twenty metres wide, oriented east-west, with the choir and altar at the east end, as is usual. The exterior is perfectly plain, with no decoration. Since only the monks were permitted inside, there is no monumental entrance, but only two simple doors, for the lay brothers on the left and the monks on the right.

The door for the monks was known as the "Door of the Dead", for the bodies of monks who had died were taken out through this door after a mass. They were first placed on a depositoire, a long shelf by the south wall, then buried directly in the earth of the cemetery.

The simple bell tower was probably constructed between 1170 and 1180, and is more than thirty meters high. Order rules prohibited bell towers of stone or of immoderate height, but exceptions were made in Provence, where Mistral winds blew away more fragile wooden structures.

Inside, the church consists of a main nave with three bays covered with a pointed barrel vault, and two side aisles. The arches supporting the vault rest upon half-columns, which rest upon carefully carved stone bases about two meters halfway up the walls of the nave.

The choir at the eastern end finishes with a half-dome vaulted apse with three semicircular arched windows, symbolizing the Trinity. Three arcades in the nave give access to the other parts of the building. There are two small chapels in the apses of the transept, aligned the same way as the main sanctuary, as in the Cistercian abbeys of Cîteaux and Clairvaux.

The chevet of the Abbey, the semi-circular space behind the altar, has no decoration, but the refinement of the workmanship, as well as the perfectly rounded form, was itself an expression of the religious ideas of the Cistercians. The circle was supposed to approach the perfection of the divine, as opposed to the square, which belonged in the secular world.

The three windows in the apse, the round oculus above, draw attention to the altar. Facing east, they catch the first morning light, and face the same direction from which Christ was expected to return to earth. They and the four small windows in the transept let in just enough light to give life to the stone inside, particularly at the time of the sunrise and sunset, which were also the times of the most important religious services, lauds and vespers. The light coming through the windows changed the color of the stone and created slowly moving shapes of darkness and light, marking the passage of time, the essential element of the life in the monastery.

The pale stained-glass windows date to 1935 - they were recreated following the model of 12th-century stained glass from Obazine Abbey in the Corrèze.

The Monks' Building

The monks building is located to the north of the church, and is connected to it by stairways, which allowed the monks direct access to services.

The dormitory is on the upper floor of the monks' building. The abbot had a separate cell on the left side, up a short stairway. The dormitory was lit by rows of semicircular windows. A monk slept in front of each window.

The Sacristy, a room two meters high, three meters wide and four meters long, with a single window, built against the church transept, was where the church vestments and sacred vestments were kept. It had direct access to the church through a door into the transept. The Sacristan was in charge of the treasury of the Abbey, rang the dormitory bell for the night services, and climbed to the roof to make astronomical observations to determine the exact time for religious services, depending upon the season.

The armarium (library) is a three-meter by three-meter room on the lower level of the monks' building, opening onto the cloister. The armarium contained the secular books used regularly by the monks. It is believed that it contained books of medicine, geometry, music, astrology, and the classical works of Aristotle, Ovid, Horace and Plato.

The Chapter House, or The Capitulary Hall, was the room where the monks met daily for a reading of one chapter of the rule of St. Benedict, and to discuss community issues. Election of new abbots also took place in this room. Its architecture - with cross-ribbed vaults resting on two columns with decorated capitals, was the most refined in the monastery, and showed the influence of the new Gothic style. The walls and columns date to about 1170, the vaulting to 1200-1240.

During the reading of the Rule and discussions, the monks were seated upon wooden benches, and the Abbot was seated at the east, facing the entry. The main sculptural element is a simple cross of the order on the south column, before which the monks would bow briefly. A hand holding a cross, the symbol of authority of the abbot, is sculpted on the capital of the north column. He was sometimes buried in this room, so that after death his memory would add to the authority of the living abbot.

The Hall of the Monks, was at the north end of the monks' building, but fell into ruins, and little remains. The room was used for making clothing, as a workshop, for the training of the new monks, and as a scriptorium, the room where manuscripts were written, since it was the only heated room in the abbey.

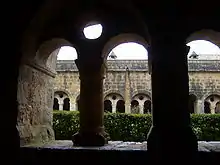

The Cloister

The cloister, in the middle of the monastery, was the center of monastery life. It measures about thirty meters on a side, is in the shape of an elongated trapezoid, and follows the terrain, sloping downward from the monks' building toward the river. Despite its odd shape, and its location on very uneven ground, it manages to maintain its architectural unity, and to blend with its natural environment; in some places the rock of the hillside becomes part of the architecture.

Construction began in 1175, making the cloister of Thoronet one of the oldest existing Cistercian cloisters. The south gallery is the oldest, followed by the east gallery, next to the chapter house, which has a more modern slightly pointed barrel vault ceiling. The construction was completed by the north gallery, beside the former refectory, and the west gallery. At a later date a second level of galleries was built, also since disappeared.

The thick walls of the galleries, their double arcades, the simple round openings over each central column, and the plain capitals give the cloister a particular power and simplicity.

A lavabo, or washing fountain, stands in the cloister in front of what had been the entrance to the refectory. It is placed in its own hexagonal structure, with a ribbed vault roof. The water came from a nearby spring, and was used by the monks for washing, shaving, tonsure, and doing laundry. The lavabo is a reconstruction, based on a fragment of the original central basin.

The former North Wing

The north wing of a Cistercian monastery, facing the church, traditionally contains the refectory (dining room), the kitchens and the calefactory, or heated sitting room. The north wing fell into ruins and was abandoned in 1791.

Building for Lay Brothers

The wing of the monastery for the lay brothers dates to the thirteenth century, well after the other buildings. The building was two stories high, with a dining room on the ground floor and a dormitory above. Two arches of the building cross the Tombareu River. The latrines were located in this part of the building.

The Cellar

The cellar is a long rectangular room attached to the east gallery of the cloister. This building has undergone numerous remodelings, and is no longer its original shape. In the sixteenth century it was turned into a wine cellar, and the wine presses can still be seen.

Le Thoronet and Le Corbusier

Thoronet Abbey had a significant influence upon the Swiss architect Le Corbusier Following the Second World War, Father Couturier, a Dominican priest and artist, who had contacts with contemporary artists Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard, invited Le Corbusier to design a convent at La Tourette, close to Lyon. Father Coutourier wrote to Le Corbusier in 1953: "I hope that you can go to Le Thoronet, and that you will like that place. It seems to me that there you will find the essence of what a monastery must have been like at the time it was built; a place where men lived by a vow of silence, devoted themselves to reflection and meditation and a communal life which has not changed very much over time." Le Corbusier visited Thoronet, and wrote an article about his visit, including the observation, "the light and the shadow are the loudspeakers of this architecture of truth." The convent that he eventually built has a number of features inspired by Thoronet, including the tower and the simple volumes, and the alternating full and empty spaces created by bright light falling on the walls.

The Influence of Le Thoronet

The British architect John Pawson also used Thoronet as an inspiration for the cistercian abbey of Novy Dvur in the Czech Republic (2004).

Le Thoronet was a source of inspiration for the Belgian poet Henry Bauchau (born 1913), who published in 1966 La Pierre Sans Chagrin.

In 1964, the French architect Fernand Pouillon published Les pierres sauvages, an historical novel in the form of the journal of a master worker at the abbey. It won the prix des Deux Magots (1965) and was praised by Umberto Eco as "a fascinating contribution to the understanding of the Middle Ages."

Sources and citations

- Le Thoronet Abbey (English Edition), Monum - Editions de Patromoine, p. 6

- Le Thoronet Abbey (English Edition), Monum - Editions de Patromoine, p. 6

- Nathalie Molina, Le Thoronet Abbey, pg. 2

- Molina, Le Thoronet Abbey, pg. 7

- Molina, Le Thoronet Abbey, pg. 13

Bibliography

- Pouillon, Fernand, 1964. Les Pierres sauvages (The Stones of the Abbey)

- Dimier, Père Anselme, 1982: L'art cistercien. Editions Zodiaque: La Pierre-qui-Vire. (in French)

- Molina, Nathalie, 1999: Le Thoronet Abbey, Monum - Editions du patrimoine.

- Denizeau, Gérard, 2003: Histoire Visuelle des Monuments de France. Larousse: Paris. (in French)

- Fleischhauer, Carsten, 2003: Die Baukunst der Zisterzienser in der Provence: Sénanque - Le Thoronet - Silvacane. Abteilung Architekturgeschichte des Kunsthistorischen Instituts der Universität zu Köln. Cologne University. (in German)

- France Mediéval, 2004: Monum, Éditions du patrimoine/Guides Gallimard. (in French)

- Bastié, Aldo, nd: Les Chemins de la Provence Romane. Éditions Ouest-France. (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abbaye du Thoronet. |