Thracian horseman

The Thracian horseman (also "Thracian Rider" or "Thracian Heros") is the name given to a recurring motif of a horseman depicted in reliefs of the Hellenistic and Roman periods in the Balkans (Thrace, Macedonia,[1][2] Moesia, roughly from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD). Inscriptions found in Romania identify the horseman as Heros (also Eros, Eron, Herros, Herron), apparently the word heros used as a proper name.[3]

The Thracian horseman is depicted as a hunter on horseback, riding from left to right. Between the horse's hooves is depicted either a hunting dog or a boar. In some instances, the dog is replaced by a lion. Its depiction is in the tradition of the funerary steles of Roman cavalrymen, with the addition of syncretistic elements from Hellenistic and Paleo-Balkanic religious or mythological tradition.

Late Roman syncretism

The Cult of the Thracian horseman was especially important in Philippi, where the Heros had the epithets of soter (saviour) and epekoos "answerer of prayers". Funerary stelae depicting the horseman belong to the middle or lower classes (while the upper classes preferred the depiction of banquet scenes).[4]

The motif most likely represents a composite figure, a Thracian heroes possibly based on Rhesus, the Thracian king mentioned in the Iliad,[5] to which Scythian, Hellenistic and possibly other elements had been added.[6]

Under the Roman Emperor Gordian III the god on horseback appears on coins minted at Tlos, in neighboring Lycia, and at Istrus, in the province of Lower Moesia, between Thrace and the Danube.[7]

In the Roman era, the "Thracian horseman" iconography is further syncretised. The rider is now sometimes shown as approaching a tree entwined by a serpent, or as approaching a goddess. These motifs are partly of Greco-Roman and partly of possible Scythian origin. The motif of a horseman with his right arm raised advancing towards a seated female figure is related to Scythian iconographic tradition. It is frequently found in Bulgaria, associated with Asclepius and Hygeia.[8]

Twin horsemen

Related to the Dioscuri motif is the so-called "Danubian Horsemen" motif of two horsemen flanking standing goddess. The motif of a standing goddess flanked by two horsemen, identified as Artemis flanked by the Dioscuri, and a tree entwined by a serpent flanked by the Dioscuri on horseback was transformed into a motif of a single horseman approaching the goddess or the tree.[9]

Other, similar figures

The motif of the Thracian horseman is not to be confused with the depiction of a rider slaying a barbarian enemy on funerary stelae, as on the Stele of Dexileos, interpreted as depictions of a heroic episode from the life of the deceased.[10]

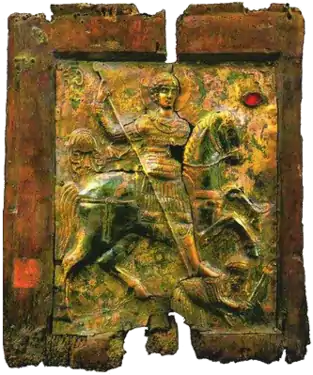

The motif of the Thracian horseman was continued in Christianised form in the equestrian iconography of both Saint George and Saint Demetrius.[11][12][13][14][15]

Gallery

- Hunter motif

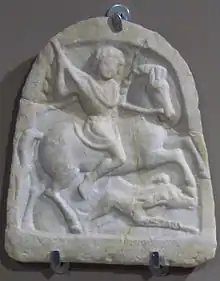

Thracian horseman with hound and boar, Greek inscription (3rd century BC), Teteven museum

Thracian horseman with hound and boar, Greek inscription (3rd century BC), Teteven museum Thracian horseman attacking a lion which is in turn attacking its prey. Madara Museum, Bulgaria

Thracian horseman attacking a lion which is in turn attacking its prey. Madara Museum, Bulgaria Statue of a Thracian horseman with lion, 3rd century, National History Museum of Bulgaria

Statue of a Thracian horseman with lion, 3rd century, National History Museum of Bulgaria Thracian horseman, funerary stele with Greek inscription, Madara Museum, Bulgaria

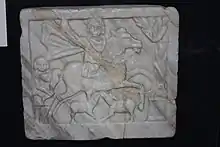

Thracian horseman, funerary stele with Greek inscription, Madara Museum, Bulgaria Thracian horseman with hound, marble votive tablet, Stara Zagora regional history museum

Thracian horseman with hound, marble votive tablet, Stara Zagora regional history museum

- Serpent-and-tree

Thracian horseman with hound and serpent-entwined tree, funerary stele for one Caius Cornelius at Philippi.

Thracian horseman with hound and serpent-entwined tree, funerary stele for one Caius Cornelius at Philippi. Thracian horseman with hounds, a serpent-entwined tree and a footman (3rd century), Constanța History and Archaeology Museum

Thracian horseman with hounds, a serpent-entwined tree and a footman (3rd century), Constanța History and Archaeology Museum Thracian horseman with hounds, footman and tree, Haskovo Historic Museum, Bulgaria

Thracian horseman with hounds, footman and tree, Haskovo Historic Museum, Bulgaria Thracian horseman with a serpent-entwined tree, Histria Museum, Romania

Thracian horseman with a serpent-entwined tree, Histria Museum, Romania Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree, the National History Museum of Bulgaria

Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree, the National History Museum of Bulgaria Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree (2nd century), Burgas Archaeological Museum, Bulgaria

Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree (2nd century), Burgas Archaeological Museum, Bulgaria Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree, Expoziţia Cultura Cucuteni

Thracian horseman with serpent-and-tree, Expoziţia Cultura Cucuteni

- Rider and goddess

Thracian rider of "Scythian" type, with raised hand, riding towards female figure, Madara Museum, Bulgaria

Thracian rider of "Scythian" type, with raised hand, riding towards female figure, Madara Museum, Bulgaria Horseman approaching seated female figure under a tree, Constanta Museum

Horseman approaching seated female figure under a tree, Constanta Museum

- Greco-Roman comparanda

Black figure Thracian cavalrymen vs. armored Greek foot soldier (Getty Villa Collection, c. 520 BC)

Black figure Thracian cavalrymen vs. armored Greek foot soldier (Getty Villa Collection, c. 520 BC) Stele of Dexileos (c. 390 BC)

Stele of Dexileos (c. 390 BC) Funerary relief of a Roman cavalryman (2nd/3rd century)

Funerary relief of a Roman cavalryman (2nd/3rd century) Funerary relief of a late (4th/5th century?) Roman cavalryman trampling a barbarian warrior, Roman Britain (Chester, Grosvenor Museum)

Funerary relief of a late (4th/5th century?) Roman cavalryman trampling a barbarian warrior, Roman Britain (Chester, Grosvenor Museum) A fragment of a decorated frieze at Felix Romuliana, a palace built by the emperor Galerius in modern-day Serbia. The fragment depicts a rider wielding an ax, and a shield-bearing soldier on foot.

A fragment of a decorated frieze at Felix Romuliana, a palace built by the emperor Galerius in modern-day Serbia. The fragment depicts a rider wielding an ax, and a shield-bearing soldier on foot..jpg.webp) "Danubian Horsemen" (Artemis flanked by the Dioscuri), votive plate found in Demir Kapija, North Macedonia

"Danubian Horsemen" (Artemis flanked by the Dioscuri), votive plate found in Demir Kapija, North Macedonia

- Medieval comparanda

The Madara Rider, equestrian rock relief in Bulgaria (c. 700)

The Madara Rider, equestrian rock relief in Bulgaria (c. 700) "St George of Labechina", Racha, Georgia (11th century), known as the oldest extant equestrian depiction of St George (but note that the horseman is trampling a human opponent rather than a dragon)

"St George of Labechina", Racha, Georgia (11th century), known as the oldest extant equestrian depiction of St George (but note that the horseman is trampling a human opponent rather than a dragon)_crop.jpg.webp) Equestrian depiction of Saints George and Demetrius

Equestrian depiction of Saints George and Demetrius

References

- Samsaris, Dimitrios C. (1984). Le culte du Cavalier thrace dans la vallée du Bas-Strymon à l' époque romaine: Recherches sur la localisation de ses sanctuaires. Dritter Internationaler Thrakologischer Kongress, Wien, 2-6 Juni 1980. Sofia. Bd. II, p. 284 sqq.

- Samsaris, Dimitrios C. (1982–1983). "Le culte du Cavalier thrace dans la colonie romaine de Philippes et dans son territoire". Ponto-Baltica. 2–3: 89–100.

- Hampartumian, Nubar. (1979). Moesia Inferior (Romanian Section) and Dacia, Volume 74, Part 4,

- Ascough, Richard S. (2003). Paul's Macedonian Associations: The Social Context of Philippians and 1 Thessalonians p. 159.

- West, Rebecca (21 December 2010). Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia. Open Road Media. p. 455. ISBN 978-1-4532-0746-8.

- Hoddinott, R.F. (1963). Early Byzantine Churches in Macedonia & Southern Serbia, 58–62

- Sabazios on coins, illustrated in the M. Halkam collection.

- Hoddinott (1963:58)

- Hoddinott (1963:59)

- Hoddinott (1963:60)

- Hoddinott (1963:61)

- de Laet, Sigfried J. (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. Routledge. pp. 233 ff. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7.

- Walter, Christopher (2003). The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition. Ashgate. pp. 88ff. ISBN 978-1-84014-694-3.

- c.f. the badly damaged wall painting of St.George in the ruins of Đurđevi stupovi, Serbia (c. 1168)

- Hoddinott (1963:61).

Bibliography

- Dumitru Tudor, Christopher Holme (trans.), Corpus Monumentorum Religionis Equitum Danuvinorum (CMRED) (1976)

- Dimitrova, Nora. "Inscriptions and Iconography in the Monuments of the Thracian Rider." Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 71, no. 2 (2002): 209-29. Accessed June 26, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3182007.

- Grbić Dragana (2013). "The Thracian hero on the Danube new interpretation of an inscription from Diana". Balcanica. 44 (44): 7–20. doi:10.2298/BALC1344007G.

- R. F. Hoddinott. (1963). Early Byzantine Churches in Macedonia & Southern Serbia Google Books

- Irina Nemeti, Sorin Nemeti, Heros Equitans in the Funerary Iconography of Dacia Porolissensis. Models and Workshops. In: Dacia LVIII, 2014, p. 241-255, http://www.daciajournal.ro/pdf/dacia_2014/art_10_nemeti_nemeti.pdf

Further reading

- Boteva, Dilyana. "À propos des "secrets" du Cavalier thrace". In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne, vol. 26, n°1, 2000. pp. 109-118. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/dha.2000.2414] ; www.persee.fr/doc/dha_0755-7256_2000_num_26_1_2414

- Mackintosh, Majorie Carol (1992). The divine horseman in the art of the western Roman Empire. PhD thesis. The Open University. pp. 132-159.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thracian horseman. |

- Uastyrdzhi

- Tetri Giorgi

- Sabazios

- Jupiter Column

- Heros Peninsula in Antarctica is named after the Thracian Horseman.