Thracians

The Thracians (/ˈθreɪʃənz/; Ancient Greek: Θρᾷκες Thrāikes; Latin: Thraci) were an Indo-European people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.[1][2] Thracians resided mainly in the Balkans, but were also located in Asia Minor and other locations in Eastern Europe.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The exact origin of Thracians is unknown, but it is believed that proto-Thracians descended from a mixture of Indo-Europeans and indigenous peoples during the second millennium BC. The proto-Thracian culture developed into the Dacian and Thracian culture.

Thracian culture was described as tribal by the ancient Greeks and Romans. They remained largely disunited with the first permanent state being the Odrysian kingdom in the fifth century BC. They faced subjugation by the Achaemenid Empire around the same time. Thracians experienced a short period of peace after the Persians were defeated by the Greeks in the Persian Wars. The Odrysian kingdom lost independence to Macedonia in the late 4th century BC, and never regained total independence following Alexander the Great's death.

The Thracians faced conquest by the Romans in the mid second century BC under whom they faced internal strife. They composed major parts of rebellions against the Romans along with the Macedonians until the Third Macedonian War. Thracians were integrated into Roman society and later converted to Christianity. The last reported use of a Thracian language was by monks in the sixth century AD.

Thracians were described as "warlike" and "barbarians" by the Greeks and Romans and were favored as mercenaries. Ancient descriptions of a vicious people are disputed and archaeology has been used since the mid-twentieth century in southern Bulgaria to identify more about them.

Thracians spoke the extinct Thracian language and shared a common culture.[1] They followed a polytheistic religion with the exception of the monotheistic Dacians who worshipped Zalmoxis. The study of the Thracians is known as Thracology.

Etymology

The first historical record of the Thracians is found in the Iliad, where they are described as allies of the Trojans in the Trojan War against the Ancient Greeks.[3] The ethnonym Thracian comes from Ancient Greek Θρᾷξ (plural Θρᾷκες; Thrāix, Thrāikes) or Θρᾴκιος (Thrāikios; Ionic: Θρηίκιος, Thrēikios), and the toponym Thrace comes from Θρᾴκη (Thrāikē; Ionic: Θρῄκη, Thrēikē).[4] These forms are all exonyms as applied by the Greeks.[5]

Mythological foundation

In Greek mythology, Thrax (by his name simply the quintessential Thracian) was regarded as one of the reputed sons of the god Ares.[6] In the Alcestis, Euripides mentions that one of the names of Ares himself was "Thrax" since he was regarded as the patron of Thrace (his golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia in Thrace).[7]

Origins

The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records. Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts of material culture. Leo Klejn identifies proto-Thracians with the multi-cordoned ware culture that was pushed away from Ukraine by the advancing timber grave culture or Srubnaya. It is generally proposed that a proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age[8] when the latter, around 1500 BC, mixed with indigenous peoples.[9] During the Iron Age (about 1000 BC) Dacians and Thracians began developing from proto-Thracians.[10]

Ancient Greek and Roman historians agreed that the ancient Thracians, who were of Indo-European stock and language, were superior fighters; only their constant political fragmentation prevented them from overrunning the lands around the northeastern Mediterranean. Although these historians characterized the Thracians as primitive partly because they lived in simple, open villages, the Thracians in fact had a fairly advanced culture that was especially noted for its poetry and music. Their soldiers were valued as mercenaries, particularly by the Macedonians and Romans.

Identity and distribution

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the fifth century BC. A strong Dacian state appeared in the first century BC, during the reign of King Burebista. The mountainous regions were home to various peoples, including the Illyrians, regarded as warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable.

Thracians inhabited parts of the ancient provinces of Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia, Mysia, Pannonia, and other regions of the Balkans and Anatolia. This area extended over most of the Balkans region, and the Getae north of the Danube as far as beyond the Bug and including Pannonia in the west.[11] There were about 200 Thracian tribes.[12]

History

Archaic period

The first Greek colonies in Thrace were founded in the eighth century BC.[13]

Thrace south of the Danube (except for the land of the Bessi) was ruled for nearly half a century by the Persians under Darius the Great, who conducted an expedition into the region from 513 to 512 BC. The Persians called Thrace "Skudra".[14]

Classical period

Achaemenid Thrace

In the first decade of the sixth century BC, the Persians conquered Thrace and made it part of their satrapy Skudra. Thracians were forced to join the invasions of European Scythia and Greece.[16] According to Herodotus, the Bithynian Thracians also had to contribute a large contingent to Xerxes' invasion of Greece in 480 BC.[16] Subjugation of Macedonia was part of Persian military operations initiated by Darius the Great (521–486) in 513: after immense preparations, a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and tried to defeat the European Scythians roaming north of the Danube River.[17] Darius' army subjugated several Thracian peoples at the same time, and virtually all other regions that touch the European part of the Black Sea, including parts of present-day Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, before returning to Asia Minor.[17][18] Darius left in Europe one of his commanders, Megabazus, whose task was to accomplish conquests in the Balkans.[17] The Persian troops subjugated gold-rich Thrace, the coastal Greek cities, and the powerful Paeonians.[17][19][20] Finally, Megabazus sent envoys to Amyntas I, King of Macedon demanding acceptance of Persian domination, which the Macedonian agreed to. By this time, many if not most Thracians were under Persian rule.[17]

By the fifth century BC, the Thracian population was large enough that Herodotus called them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians), and potentially the most powerful, if not for their lack of unity.[21] The Thracians in classical times were broken up into a large number of groups and tribes, though a number of powerful Thracian states were organized, such as the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace and the Dacian kingdom of Burebista. The peltast, a type of soldier of this period, probably originated in Thrace.

During this period, a subculture of celibate ascetics called the "ctistae" lived in Thrace, where they served as philosophers, priests and prophets.

Odrysian Kingdom

The Odrysian Kingdom was a state union of over 40 Thracian tribes[22] and 22 kingdoms[23] that existed between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD. It consisted mainly of present-day Bulgaria, spreading to parts of Southeastern Romania (Northern Dobruja), parts of Northern Greece and parts of modern-day European Turkey.

Macedonian Thrace

During this period, contacts between the Thracians and Classical Greece intensified.

After the Persians withdrew from Europe and before the expansion of the Kingdom of Macedon, Thrace was divided into three regions (east, central, and west). A notable ruler of the East Thracians was Cersobleptes, who attempted to expand his authority over many of the Thracian tribes. He was eventually defeated by the Macedonians.

The Thracians were typically not city-builders[24][25] and their only polis was Seuthopolis.[26][27]

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such as Lysimachus of the Diadochi.

In 279 BC, Celtic Gauls advanced into Macedonia, southern Greece and Thrace. They were soon forced out of Macedonia and southern Greece, but they remained in Thrace until the end of the third century BC. From Thrace, three Celtic tribes advanced into Anatolia and established the kingdom of Galatia.

In western parts of Moesia, Celts (Scordisci) and Thracians lived alongside each other, as evident from the archaeological findings of pits and treasures, spanning from the third century BC to the first century BC.[28]

Roman Thrace

During the Macedonian Wars, conflict between Rome and Thrace was unavoidable. The rulers of Macedonia were weak, and Thracian tribal authority resurged. But after the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, Roman authority over Macedonia seemed inevitable, and the governance of Thrace passed to Rome.

Initially, Thracians and Macedonians revolted against Roman rule. For example, the revolt of Andriscus, in 149 BC, drew the bulk of its support from Thrace. Incursions by local tribes into Macedonia continued for many years, though a few tribes, such as the Deneletae and the Bessi, willingly allied with Rome.

After the Third Macedonian War, Thrace acknowledged Roman authority. The client state of Thracia comprised several tribes.

Roman rule

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. The Sapaei tribe came to the forefront initially under the rule of Rhascuporis. He was known to have granted assistance to both Pompey and Caesar, and later supported the Republican armies against Antonius and Octavian in the final days of the Republic.

The heirs of Rhascuporis became as deeply enmeshed in political scandal and murder as were their Roman masters. A series of royal assassinations altered the ruling landscape for several years in the early Roman imperial period. Various factions took control with the support of the Roman Emperor. The turmoil would eventually end with one final assassination.

After Rhoemetalces III of the Thracian Kingdom of Sapes was murdered in AD 46 by his wife, Thracia was incorporated as an official Roman province to be governed by Procurators, and later Praetorian prefects. The central governing authority of Rome was in Perinthus, but regions within the province were under the command of military subordinates to the governor. The lack of large urban centers made Thracia a difficult place to manage, but eventually the province flourished under Roman rule. However, Romanization was not attempted in the province of Thracia. The Balkan Sprachbund does not support Hellenization.

Roman authority in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia. The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and distance from Roman authority, certainly inspired local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanic tribes. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary fortresses to supplement the defense.

Thracians in Moesia were Romanized. Those in Thrace and surrounding areas would come to be known as the Bessi. In the 6th century AD the Bessian (i.e. Thracian) language was reportedly still in use by monks at a Mount Sinai monastery.[29][30]

Barbarians

Thracians were regarded by other peoples as warlike, ferocious, and bloodthirsty.[31][32] They were seen as "barbarians" by ancient Greeks and Romans. Plato in his Republic groups them with the Scythians,[33] calling them extravagant and high spirited; and his Laws portrays them as a warlike nation, grouping them with Celts, Persians, Scythians, Iberians and Carthaginians.[34] Polybius wrote of Cotys's sober and gentle character being unlike that of most Thracians.[35] Tacitus in his Annals writes of them being wild, savage and impatient, disobedient even to their own kings.[36]

Polyaenus and Strabo write how the Thracians broke their pacts of truce with trickery.[37][38] The Thracians struck their weapons against each other before battle, "in the Thracian manner," as Polyaneus testifies.[39] Diegylis was considered one of the most bloodthirsty chieftains by Diodorus Siculus. An Athenian club for lawless youths was named after the Triballi.[40]

According to ancient Roman sources, the Dii[41] were responsible for the worst[42] atrocities of the Peloponnesian War, killing every living thing, including children and dogs in Tanagra and Mycalessos.[41] Thracians would impale Roman heads on their spears and rhomphaias such as in the Kallinikos skirmish at 171 BC.[42] Herodotus writes that "they sell their children and let their maidens commerce with whatever men they please".[43]

The accuracy and impartiality of these descriptions have been called into question in modern times, given the seeming embellishments in Herodotus's histories, for one.[44] Archaeologists have attempted to piece together a fuller understanding of Thracian culture through study of their artifacts.[45]

Aftermath and legacy

The ancient languages of these people and their cultural influence were highly reduced due to the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Ancient Macedonians, Romans, Celts, Huns, Goths, Scythians, Sarmatians and Slavs, accompanied by, hellenization, romanization and later slavicisation. However, the Thracians as a group did not entirely disappear, with the Bessi surviving at least until the late 4th century. Towards the end of the 4th century, Nicetas the Bishop of Remesiana brought the gospel to "those mountain wolves", the Bessi.[46] Reportedly his mission was successful, and the worship of Dionysus and other Thracian gods was eventually replaced by Christianity. In 570, Antoninus Placentius said that in the valleys of Mount Sinai there was a monastery in which the monks spoke Greek, Latin, Syriac, Egyptian and Bessian. The origin of the monasteries is explained in a medieval hagiography written by Simeon Metaphrastes, in Vita Sancti Theodosii Coenobiarchae in which he wrote that Theodosius the Cenobiarch founded on the shore of the Dead Sea a monastery with four churches, in each being spoken a different language, among which Bessian was found. The place where the monasteries were founded was called "Cutila", which may be a Thracian name.[47] The further fate of the Thracians is a matter of dispute. Some authors like Schramm derived the Albanians from the Christian Bessi, or Bessians, an early Thracian people who were pushed westwards into Albania,[48] while more mainstream historians support Illyrian-Albanian continuity or a possible Thraco-Illyrian creole.[49][50][51][52] Most probably the remnants of the Thracians were assimilated into the Roman and later in the Byzantine society and became part of the ancestral groups of the modern Southeastern Europeans.

Culture

Language

Religion

One notable cult that existed in Thrace, Moesia and Scythia Minor was that of the "Thracian horseman", also known as the "Thracian Heros", at Odessos (near Varna) known by a Thracian name as Heros Karabazmos, a god of the underworld, who was usually depicted on funeral statues as a horseman slaying a beast with a spear.[53][54][55] Dacians had a monotheistic religion based on the god Zalmoxis.[56] The supreme Balkan thunder god Perkon was part of the Thracian pantheon, although cults of Orpheus and Zalmoxis likely overshadowed his.[57]

Some think that the Greek god Dionysus evolved from the Thracian god Sabazios.[58]

Marriage

The Thracians were polygamous. Menander puts it: "All Thracians, especially us and the Getae, are not much abstaining, because no one takes less than ten, eleven, twelve wives, some even more. If one dies and has only four or five wives he is called ill-fated, unhappy and unmarried."[59] According to Herodotus virginity among women was not valued, and unmarried Thracian women could have sex with any man they wished to.[59] There were men perceived as holy Thracians, who lived without women and were called "ktisti".[59] In myth Orpheus became attracted to men after the death of Eurydice and is thought of as the establisher of homosexuality among Thracian men. Because he advocated love between men and turning away from loving women he was killed by the Bistones women.[59]

Warfare

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins.[60] Thracian peltasts had a notable influence in Ancient Greece.[61]

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.

Physical appearance

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the name Rufus inscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people with red hair[62] which led to associating the name with slaves when the Romans enslaved this particular group.[63] Ancient Greek artwork often depicts Thracians as redheads.[64] Rhesus of Thrace, a mythological Thracian king, was so named because of his red hair and is depicted on Greek pottery as having red hair and a red beard.[64] Ancient Greek writers also described the Thracians as red-haired. A fragment by the Greek poet Xenophanes describes the Thracians as blue-eyed and red haired:

...Men make gods in their own image; those of the Ethiopians are black and snub-nosed, those of the Thracians have blue eyes and red hair.[65]

Bacchylides described Theseus as wearing a hat with red hair, which classicists believe was Thracian in origin.[66] Other ancient writers who described the hair of the Thracians as red include Hecataeus of Miletus,[67] Galen,[68] Clement of Alexandria,[69] and Julius Firmicus Maternus.[70]

Nevertheless, academic studies have concluded that people often had different physical features from those described by primary sources. Ancient authors described as red-haired several groups of people. They claimed that all Slavs had red hair, and likewise described the Iranic Scythians as red haired. According to Dr. Beth Cohen, Thracians had "the same dark hair and the same facial features as the Ancient Greeks."[71] On the other hand, Dr. Aris N. Poulianos states that Thracians, like modern Bulgarians, belonged mainly to the Aegean anthropological type.[72]

Notable people

This is a list of historically important personalities being entirely or partly of Thracian ancestry:

- Orpheus, mythological figure considered chief among poets and musicians; king of the Thracian tribe of Cicones

- Spartacus, Thracian gladiator who led a large slave uprising in Southern Italy in 73–71 BC and defeated several Roman legions in what is known as the Third Servile War

- Amadocus, Thracian King, the Amadok Point was named after him

- Teres I, Thracian King who united many tribes of Thrace under the banner of the Odrysian state

- Sitalces, King of the Odrysian state; an ally of the Athenians during the Peloponnesian War

- Burebista, King of Dacia

- Decebalus, King of Dacia

- Maximinus Thrax, Roman Emperor from 235 to 238.[73]

- Aureolus, Roman military commander

- Galerius, Roman Emperor from 305 to 311; born to a Thracian father and Dacian mother

- Licinius, Roman Emperor from 308 to 324

- Maximinus Daia or Maximinus Daza, Roman Emperor from 308 to 313

- Justin I, Eastern Roman Emperor and founder of the Justinian dynasty

- Justinian the Great, Eastern Roman Emperor; either Illyrian or Thracian, born in Dardania

- Belisarius, Eastern Roman general of reputed Illyrian or Thracian origin

- Marcian, Eastern Roman Emperor from 450 to 457; either Illyrian or Thracian

- Leo I the Thracian, Eastern Roman Emperor from 457 to 474

- Bouzes or Buzes, Eastern Roman general active during the reign of Justinian the Great (r. 527–565)

- Coutzes or Cutzes, general of the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Emperor Justinian I

Thracology

Archaeology

The branch of science that studies the ancient Thracians and Thrace is called Thracology. Archaeological research on the Thracian culture started in the 20th century, especially after World War II, mainly in southern Bulgaria. As a result of intensive excavations in the 1960s and 1970s a number of Thracian tombs and sanctuaries were discovered. Most significant among them are: the Tomb of Sveshtari, the Tomb of Kazanlak, Tatul, Seuthopolis, Perperikon the Tomb of Aleksandrovo in Bulgaria and Sarmizegetusa in Romania and others.

Also a large number of elaborately crafted gold and silver treasure sets from the 5th and 4th century BC were unearthed. In the following decades, those were exhibited in museums around the world, thus calling attention to ancient Thracian culture. Since the year 2000, Bulgarian archaeologist Georgi Kitov has made discoveries in Central Bulgaria, in an area now known as "The Valley of the Thracian Kings". The residence of the Odrysian kings was found in Starosel in the Sredna Gora mountains.[74][75] A 1922 Bulgarian study claimed that there were at least 6,269 necropolises in Bulgaria.[76]

Genetics

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in April 2019 examined the mtDNA of 25 Thracian remains in Bulgaria from the 3rd and 2nd millenniums BC. They were found to harbor a mixture of ancestry from Western Steppe Herders (WSHs) and Early European Farmers (EEFs).[77]

Gallery

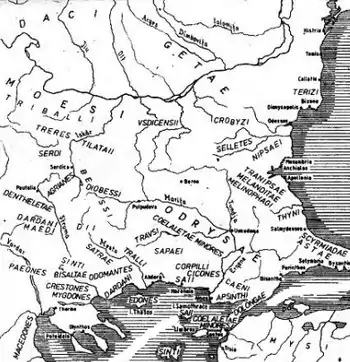

Thracian tribes and heroes.

Thracian tribes and heroes. Map of the territory of Philip II of Macedon.

Map of the territory of Philip II of Macedon. Kingdom of Lysimachus and the Diadochi.

Kingdom of Lysimachus and the Diadochi. Golden Dacian helmet of Cotofenesti, in Romania.

Golden Dacian helmet of Cotofenesti, in Romania. Gold coins that have been minted by the Dacians, with the legend ΚΟΣΩΝ.

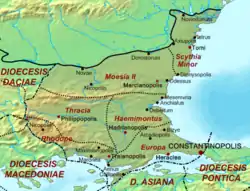

Gold coins that have been minted by the Dacians, with the legend ΚΟΣΩΝ. Map of the Diocese of Thrace (Dioecesis Thraciae) c. 400 AD.

Map of the Diocese of Thrace (Dioecesis Thraciae) c. 400 AD.

A gold Thracian treasure from Panagyurishte, Bulgaria.

A gold Thracian treasure from Panagyurishte, Bulgaria. Thracian tomb Shushmanets build in 4th century BC

Thracian tomb Shushmanets build in 4th century BC

The interior of the Sveshtari tomb

The interior of the Sveshtari tomb

Bronze head of Seuthes III from his tomb

Bronze head of Seuthes III from his tomb

Interior of Tomb of Seuthes III

Interior of Tomb of Seuthes III

See also

- Akrokomai

- Dacia and Dacians

- Illyria and Illyrians

- List of rulers of Thrace and Dacia

- List of Thracian tribes

- List of ancient Daco-Thracian peoples and tribes

- Odrysian kingdom

- Orphism (religion)

- Paeonia (kingdom)

- Thracian warfare

- Cimmerians

- Thraco-Cimmerian

- Thraco-Dacian

- Thraco-Illyrian

- Tiras

References

- Webber 2001, p. 3. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, southern Russia, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, diveded among up to 40 tribes."

- Modi et al. 2019, p. 1. "One of the best documented Indo-European civilizations that inhabited Bulgaria is the Thracians..."

- Boardman, John (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 836. ISBN 0-521-85073-8.

- Navicula Bacchi – Θρηικίη (Accessed: October 13, 2008).

- John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 597. "We have no way of knowing what the Thracians called themselves and if indeed they had a common name... Thus the name of Thracians and that of their country were given by the Greeks to a group of Hellenic tribes occupying the territory..."

- Lemprière and Wright, p. 358. "Mars was father of Cupid, Anteros, and Harmonia, by the goddess Venus. He had Ascalaphus and Ialmenus by Astyoche; Alcippe by Agraulos; Molus, Pylus, Euenus, and oThestius, by Demonice the daughter of Agenor. Besides these, he was the reputed father of Romulus, Oenomaus, Bythis, Thrax, Diomedes of Thrace, &c."

- Euripides, p. 95. "[Line] 58. 'Thrace's golden shield' – One of the names of Ares was Thrax, he being the Patron of Thrace. His golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia there.. Like the other Thracian bucklers, it was of the shape of a half-moon ('Pelta'). His 'festival of Mars Gradivus' was kept annually by the Latins in the month of March, when this sort of shield was displayed."

- Hoddinott, p. 27.

- Casson, p. 3.

- John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1982, p. 53. "Yet we cannot identify the Thracians at that remote period, because we do not know for certain whether the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had separated by then. It is safer to speak of Proto-Thracians from whom there developed in the Iron Age..."

- The catalogue of Kimbell Art Museum's 1998 exhibition Ancient Gold: The Wealth of the Thracians indicates a historical extent of Thracian settlement including most of the Ukraine, all of Hungary and parts of Slovakia. (Kimbell Art – Exhibitions)

- Mircea Eliade, Ioan Petru Culianu, Humanitas, Bucuresti, 1993, p.267. ISBN 978-973-681-962-9

- Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 1515. "From the 8th century BC the coast Thrace was colonised by Greeks."

- Susan Wise Bauer. The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome. W.W. Norton & Company, 2007, p. 517. "Megabazus turned Thrace into a new Persian satrapy, Skudra."

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, ISBN 0-19-860641-9, page 1514,"The kingdom of the Odrysae, the leading tribe of Thrace extended in present-day Bulgaria, Turkish Thrace (east of the Hebrus) and Greece between the Hebrus and Strymon except for the coastal strip with its Greek cities."

- Webber, Christopher (25 September 2001). The Thracians, 700 BC - AD 46. ISBN 9781841763293. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (7 July 2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. ISBN 9781444351637. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, ISBN 0-19-860641-9, page 1515, "The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Howe & Reames 2008, p. 239.

- Herodotus. Histories, Book V.

- Thrace. The History Files.

- "Interview: Capital of largest Thracian kingdom discovered in Bulgaria". xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 612. "Thrace possessed only fortified areas, and cities such as Cabassus would have been no more than large villages. In general the population lived in villages and hamlets."

- John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 612. "According to Strabo (vii.6.1cf.st.Byz.446.15) the Thracian suffix -bria meant polis but it is an inaccurate translation."

- Mogens Herman Hansen. An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation. Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 888. "It was meant to be a polis but there was no reason to think that it was anything other than a native settlement."

- Webber 2001.

- "Funerary Practices in Europe, before and after the Roman Conquest" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- Simeon Metaphrastes. Vita Sancti Theodosii Coenobiarchae

- Antoninus of Piacenza

- Webber 2001, p. 3.

- Duncan Head and Ian Heath. Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars 359 BC to 146 BC: Organisation, Tactics, Dress and Weapons. Wargames Research Group, 1982, p. 51.

- Plato. The Republic: "Take the quality of passion or spirit;--it would be ridiculous to imagine that this quality, when found in States, is not derived from the individuals who are supposed to possess it, e.g. the Thracians, Scythians, and in general the northern nations;"

- Plato. Laws: "Are we to follow the custom of the Scythians, and Persians, and Carthaginians, and Celts, and Iberians, and Thracians, who are all warlike nations, or that of your countrymen, for they, as you say, altogether abstain?"

- Polybius. Histories, 27.12.

- Tacitus. The Annals: "In the Consulship of Lentulus Getulicus and Caius Calvisius, the triumphal ensigns were decreed to Poppeus Sabinus for having routed some clans of Thracians, who living wildly on the high mountains, acted thence with the more outrage and contumacy. The ground of their late commotion, not to mention the savage genius of the people, was their scorn and impatience, to have recruits raised amongst them, and all their stoutest men enlisted in our armies; accustomed as they were not even to obey their native kings further than their own humour, nor to aid them with forces but under captains of their own choosing, nor to fight against any enemy but their own borderers."

- Polyaenus. Strategems. Book 7, The Thracians.

- Strabo. History, 9.401 (9.2.4).

- Polyaenus. Strategems. Book 7, Clearchus.

- Webber 2001, p. 6.

- Zofia Archibald. The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace: Orpheus Unmasked (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology). Clarendon Press, 1998, p. 100.

- Webber 2001, p. 7.

- Herodotus (trans. G.C. Macaulay). The History of Herodotus (Volume II). "Of the other Thracians the custom is to sell their children to be carried away out of the country; and over their maidens they do not keep watch, but allow them to have commerce with whatever men they please, but over their wives they keep very great watch."

- Hu, Rollin (February 11, 2016). "Herodotus' Histories and its reliability". The Johns Hopkins News-Letter. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Klass, Rosanne (June 26, 1977). "Thracian Clues To Our 'Barbarian' Heritage". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Gottfried Schramm: A New Approach to Albanian History 1994

- Linguistics Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- 1994 Gottfried Schramm: A New Approach to Albanian History

- Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 978-1-4051-0316-9

- Stipčević, Alexander. Iliri (2nd edition). Zagreb, 1989 (also published in Italian as "Gli Illiri")

- NGL Hammond The Relations of Illyrian Albania with the Greeks and the Romans. In Perspectives on Albania, edited by Tom Winnifrith, St. Martin's Press, New York 1992

- "Johann Thunmann: On the History and Language of the Albanians and Vlachs"

- Lurker, Manfred (1987). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons. p. 151.

- Nicoloff, Assen (1983). Bulgarian Folklore. p. 50.

- Isaac, Benjamin H. (1986). The Greek Settlements in Thrace Until the Macedonian Conquest. p. 257.

- Eliade, Mircea (1985). De Zalmoxis à Gengis-Khan. p. 35.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas.Where we come from: the origin of the Lithuanian people, Science & Encyclopedia Publishing Institute, ISBN 9785420015728 pp. 58

- Patricia Turner and Charles Russell Coulter. Dictionary of Ancient Deities. Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 152.

- Ангел Гоев. Еротичното в историята Том 2 (PDF). pp. 8, 13, 14. ISBN 978-954-400-514-6.

- Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. 27 June 2016. p. 552. ISBN 978-1-61069-020-1.

- Jan G. P. Best (1969). Thracian Peltasts: And Their Influence on Greek Warfare. Wolters-Noordhoff.

- Webber 2001, p. 17.

- Racism: A Global Reader, Thomas Reilly, Stephen Kaufman, Angela Bodino, 2002, p. 121-122

- Not the classical ideal: Athens and the construction of the other in Greek art, Beth Cohen, 2000, p. 371.

- Diels, B16,Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, 1903, pp.38–58 (Xenophanes fr. B16, Diels-Kranz, Kirk/Raven no. 171 [= Clem. Alex. Strom. Vii.4]

- Ode 18, Dithyramb 4, verse 51, quoted in Bacchylides: a selection By Bacchylides, Herwig Maehler, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 191.

- Hecataeus mentions a Thracian tribe called the Xanthoi (Nenci 1954: fragment 191 ) apparently named for their fair (red) hair (Helm 1988: 145), quoted in Indo-European origins: the anthropological evidence Institute for the Study of Man, John v. day, 2001 p. 39.

- De Temp. II. 5

- Clem. Alex. Strom. Vii.4

- Matheseos Libri Octo, II. 1, quoted in Ancient Astrology Theory and Practice, Jean Rhys Bram 2005, pp. 14, 29.

- Beth Cohen (ed.) Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden, 2000.

- Poulianos, Aris N., 1961, The Origin of the Greeks, Ph.D. thesis, University of Moscow, supervised by F.G.Debets

- Most likely he was of Thraco-Roman origin, believed so by Herodian in his writings,(Herodian, 7:1:1-2) and the references to his "Gothic" ancestry might refer to a Getae origin (the two populations were often confused by later writers, most notably by Jordanes in his Getica), as suggested by the paragraphs describing how "he was singularly beloved by the Getae, moreover, as if he were one of themselves" and how he spoke "almost pure Thracian".(Historia Augusta, Life of Maximinus, 2:5)

- "Bulgarian Archaeologists Make Breakthrough in Ancient Thrace Tomb". Novinite. March 11, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- "Bulgarian Archaeologists Uncover Story of Ancient Thracians' War with Philip II of Macedon". Novinite. June 21, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Izvestii︠a︡: Bulletin. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. 1922. p. 104.

- Modi et al. 2019, p. 1.

Sources

- Best, Jan G. P. (1969). Thracian Peltasts: And Their Influence on Greek Warfare. Wolters-Noordhoff.

- Howe, Timothy; Reames, Jeanne (2008). Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza. Regina Books. ISBN 978-1-930-05356-4.

- Marazov, Ivan Marazov, ed. (1998). Ancient gold: the wealth of the Thracians : treasures from the Republic of Bulgaria. Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Trust for Museum Exhibitions, in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Bulgaria.

- Best, Jan and De Vries, Nanny. Thracians and Mycenaeans. Boston, MA: E.J. Brill Academic Publishers, 1989. ISBN 90-04-08864-4.

- Cardos, G., Stoian V., Miritoiu N., Comsa A., Kroll A., Voss S., Rodewald A. "Paleo-mtDNA analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian populations from South-East of Romania". Romanian Journal of Legal Medicine 12(4), pp. 239–246, 2004. (Article)

- Casson, Lionel (Summer 1977). "The Thracians". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 35 (1): 3–6. doi:10.2307/3258667. JSTOR 3258667.

- Hoddinott, Ralph F. The Thracians. Thames & Hudson, 1981. ISBN 0-500-02099-X.

- Modi, Alessandra; et al. (April 1, 2019). "Ancient human mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Bulgaria: new insights into the genetic history of Thracians". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 13 (10): 5412. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41945-0. PMC 6443937. PMID 30931994.

- Samsaris, D. (1980). The Hellenization of Thrace during the Hellenic and Roman Antiquity. Thessaloniki (Doctoral thesis in Greek).

- Webber, Christopher (2001). The Thracians. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-329-2.

- Webber, Christopher, The Gods of Battle, The Thracians at War 1500 BC- 150 AD Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2011. ISBN 9781844158355

Further reading

- Kaul, Flemming. "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Thracian Art, Celtic Motifs". In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 37, 2011. pp. 81-110. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2011.2326] www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2011_num_37_1_2326

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Thrace and Ancient Thracians. |