Three Beauties of the Present Day

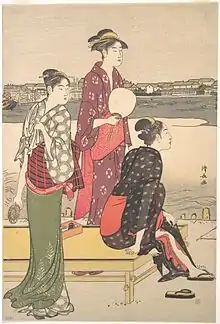

Three Beauties of the Present Day (当時三美人, Tōji San Bijin) is a nishiki-e colour woodblock print from c. 1792–93 by Japanese ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806). The triangular composition depicts the profiles of three celebrity beauties of the time: geisha Tomimoto Toyohina, and teahouse waitresses Naniwaya Kita and Takashima Hisa. The print is also known under the titles Three Beauties of the Kansei Era (寛政三美人, Kansei San Bijin) and Three Famous Beauties (高名三美人, Kōmei San Bijin).

| Three Beauties of the Present Day | |

|---|---|

| Japanese: 当時三美人 Tōji San Bijin | |

_Three_Beauties_of_the_Present_Time%252C_MFAB_21.6382.jpg.webp) First printing, in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Left: Takashima Hisa; middle: Tomimoto Toyohina; right: Naniwaya Kita | |

| Artist | Kitagawa Utamaro |

| Year | c. 1793 |

| Type | Nishiki-e colour woodblock print |

| Dimensions | 37.9 cm × 24.9 cm (14.9 in × 9.8 in) |

Utamaro was the leading ukiyo-e artist in the 1790s in the bijin-ga genre of pictures of female beauties. He was known for his ōkubi-e, which focus on the heads. The three models in Three Beauties of the Present Day were frequent subjects of Utamaro's portraiture. Each figure in the work is adorned with an identifying family crest. The portraits are idealized, and at first glance their faces seem similar, but subtle differences in their features and expressions can be detected—a level of realism at the time unusual in ukiyo-e, and a contrast with the stereotyped beauties in earlier masters such as Harunobu and Kiyonaga. The luxurious print was published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō and made with multiple woodblocks—one for each colour—and the background was dusted with muscovite to produce a glimmering effect. It is believed to have been quite popular, and the triangular positioning became a vogue in the 1790s. Utamaro produced several other pictures with the same arrangement of the same three beauties, and all three appeared in numerous other portraits by Utamaro and other artists.

Background

Ukiyo-e art flourished in Japan during the Edo period from the 17th to 19th centuries, and took as its primary subjects courtesans, kabuki actors, and others associated with the "floating world" lifestyle of the pleasure districts. Alongside paintings, mass-produced woodblock prints were a major form of the genre.[1] In the mid-18th century full-colour nishiki-e prints became common, printed using a large number of woodblocks, one for each colour.[2] Towards the close of the 18th century there was a peak in both the quality and quantity of work.[3] A prominent genre was bijin-ga ("pictures of beauties"), which depicted most often courtesans and geisha at leisure, and promoted the entertainments to be found in the pleasure districts.[4]

Katsukawa Shunshō introduced the ōkubi-e "large-headed picture" in the 1760s;[5] he and other members of the Katsukawa school such as Shunkō popularized the form for yakusha-e actor prints, as well as the dusting of mica in the backgrounds to produce a glittering effect.[6] Kiyonaga was the pre-eminent portraitist of beauties in the 1780s, and the tall, graceful beauties in his work had a great influence on Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806), who was to succeed him in fame.[7] Utamaro studied under Toriyama Sekien (1712–1788), who had trained in the Kanō school of painting. Around 1782, Utamaro came to work for the publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō.[8]

In 1791, Tsutaya published three books by Santō Kyōden in the sharebon genre of humorous tales of adventures in the pleasure quarters; deeming them too frivolous, the military government punished the author with fifty days in manacles and fined the publisher half his property. His luck was reversed shortly after with a new success: Utamaro began producing the first bijin ōkubi-e portraits, adapting ōkubi-e to the bijin-ga genre. Their popularity restored Tsutaya's fortunes[9] and made Utamaro's in the 1790s.[10]

Description and analysis

Three Beauties of the Present Day is considered one of Utamaro's representative early works.[11] It depicts the profiles of three celebrity beauties of 1790s Edo (modern Tokyo).[12] Utamaro's subjects were not courtesans, as was expected in ukiyo-e, but young women known around Edo for their beauty.[13] These three were frequent subjects of Utamaro's art, and often appeared together.[14] Each is identified with an associated family crest.[15]

In the centre poses Tomimoto Toyohina,[lower-alpha 1] a famed geisha of the Tamamuraya house in the Yoshiwara pleasure district.[16] She was dubbed "Tomimoto" having made her name playing Tomimoto-bushi music on the shamisen.[14] Like the other two models, she has her hair up in the fashionable Shimada style that was popular at the time. Contrasted with the homelier teahouse-girl garments of the other two models, she is dressed in the showier geisha style.[17] The Tomimoto crest's Japanese primrose design adorns the sleeve of her kimono.[18] Toyohina's birthdate is unknown.[19]

To the right Naniwaya Kita,[lower-alpha 2] also known as "O-Kita",[12] well-known daughter of the owner of a teahouse in Asakusa[20] near the temple Sensō-ji. She is said to have been fifteen[lower-alpha 3] in the portrait,[19] in which she wears a patterned[12] black kimono[17] and holds an uchiwa hand fan printed with her family emblem, a paulownia crest.[14]

At left is Takashima Hisa,[lower-alpha 4][12] also called "O-Hisa", from Yagenbori in Ryōgoku.[21] She was the eldest daughter of Takashima Chōbei, the owner of a roadside teahouse at his home called Senbeiya[14] in which Hisa worked attracting customers.[19] Tradition places her age at sixteen[lower-alpha 5] when the portrait was made, and there is a subtly discernible difference in maturity in the faces of the two teahouse girls.[22] Hisa holds a hand towel over her left shoulder[17] and an identifying three-leaved daimyo oak crest decorates her kimono.[14]

- Crests of the three beauties

Hisa's three-leaved oak crest

Hisa's three-leaved oak crest Toyohina's Japanese primrose crest

Toyohina's Japanese primrose crest Kita's paulownia crest

Kita's paulownia crest

Rather than attempting to capture a realistic portrayal of the three, Utamaro idealizes their likenesses.[12] To many viewers, the faces in this and other portraits of the time seem little individuated, or perhaps not at all. Others emphasize the subtle differences[14] that distinguish the three in the shapes of the mouths, noses,[12] and eyes:[20] Kita has plump cheeks and an innocent expression;[19] her eyes are almond-shaped, and the bridge of her nose high;[20] Hisa has a stiffer, proud expression,[23] and the bridge of Hisa's nose is lower and her eyes rounder than Kita's;[20] Toyohina's features fall in between,[20] and she has an air of being older and more intellectual.[19]

The print is a vertical ōban of 37.9 × 24.9 centimetres (14.9 × 9.8 in),[24] and is a nishiki-e—a full-colour ukiyo-e print made from multiple woodblocks, one for each colour; the inked blocks are pressed on Japanese handmade paper. To produce a glittering effect the background is dusted with muscovite, a variety of mica. The image falls under the genres of bijin-ga ("portraits of beauties") and ōkubi-e ("big-headed pictures"), the latter a genre Utamaro pioneered and was strongly associated with.[12]

The composition of the three figures is triangular, a traditional arrangement Tadashi Kobayashi compares to The Three Vinegar Tasters,[lower-alpha 6] in which Confucius, Gautama Buddha, and Laozi symbolize the unity of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism; similarly, Kobayashi says, Utamaro demonstrates the unity of the three competing celebrity beauties in the print.[15]

- Portraits of the three Kansei beauties by Utamaro

_Takashima_O-Hisa.jpg.webp) Takashima Hisa, c. 1792–93

Takashima Hisa, c. 1792–93_Tomimoto_Toyohisa_reading_a_letter_(Rijksmuseum%252C_cropped).jpg.webp) Tomimoto Toyohina, c. 1792–1796

Tomimoto Toyohina, c. 1792–1796_Naniwaya_O-Kita.jpg.webp) Naniwaya Kita, c. 1793

Naniwaya Kita, c. 1793

Publication and legacy

Evening on the Banks of the Sumida River (right half of a diptych), late 18th century

The print was designed by Utamaro and published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō in the fourth or fifth year of the Kansei era of the traditional Japanese era divisions[14] (c. 1792–93).[24] Tsutaya's publisher's seal is printed on the left above Hisa's head, and a round censor's seal appears above it. Utamaro's signature is printed in the bottom left.[22]

Fumito Kondō considered the print revolutionary; such expressive, individualized faces are not seen in the stereotyped figures in the works of Utamaro's predecessors such as Harunobu and Kiyonaga,[19] and it was the first time in ukiyo-e history that the beauties were drawn from the general urban population rather than the pleasure quarters.[25]

Records indicate Kita was rated highly in teahouse rankings, and that curious fans flooded her father's teahouse; it is said this caused her to become arrogant and cease to serve tea unless called for. Hisa ranked lower, though still appears to have been quite popular—a wealthy merchant offered 1500 ryō for her, but her parents refused and she continued to work at the teahouse.[26] Utamaro took advantage of this rivalry in his art, going as far as to portray the two tearoom beauties in tug-of-war and other competitions, with deities associated with their neighbourhoods supporting them: Buddhist guardian deity Acala was associated with Yagenbori, and supported Hisa; Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, was associated with the temple Sensō-ji in Asakusa, and supported Kita.[27]

The triangular positioning of three figures became something of a vogue in prints of the mid-1790s. The "Three Beauties of the Kansei Era" normally refer to the three who appear in this print; on occasion, Utamaro replaced Toyohina with Kikumoto O-Han.[14] Utamaro placed the three beauties in the same composition three or four years later in a print called Three Beauties,[lower-alpha 7] in which Hisa holds a teacup saucer in her left hand rather than a handkerchief, and Kita holds her fan in both hands. To Eiji Yoshida, the figures in this print lack the personalities that were the charm of the earlier. Yoshida thought less of the further undifferentiated personalities of a later print with the same triangular composition, Three Beauties Holding Bags of Snacks,[lower-alpha 8] published by Yamaguchiya.[11] As testimony to their popularity, the three models often appeared in the works of other artists,[22] and Utamaro continued to use them in other prints, individually or in pairs.[14]

There are no records of sales figures of ukiyo-e from the era in which the print was made. Determining the popularity of a print requires indirect means, one of which is to compare the differences in surviving copies. For example, the more copies printed, the more the woodblocks wore down, resulting in loss of line clarity and details. Another example is that publishers often made changes to the blocks in later print runs. Researchers use clues such as these to determine whether prints were frequently reprinted—a sign of their popularity.[28] The original printing of Three Beauties of the Present Day had the title in a bookmark-shape in the top right corner with the names of the three beauties to its left. Only two copies of this state are believed to have survived; they are in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Koishikawa Ukiyo-e Art Museum in Tokyo.[12] Later printings lack the title, the names of the beauties, or both, and the position of the publisher's and censor's seals varies slightly.[22] The reasons for the changes are subject to speculation, such as that the beauties may have moved away, or their fame may have fallen.[22] Based on clues such as these changes, researchers believe this print was a popular hit for Utamaro and Tsutaya.[29]

- Group portraits of the three Kansei beauties by Utamaro

From_Bijin-ga_(Pictures_of_Beautiful_Women)%252C_published_by_Tsutaya_Juzaburo_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Variations appeared in later printings—the names are missing on this copy of the print from the Toledo Museum of Art.

Variations appeared in later printings—the names are missing on this copy of the print from the Toledo Museum of Art._Three_Beauties%E2%80%94Okita%252C_Ohisa%252C_and_Toyohina.jpg.webp) Three Beauties, c. 1792–93

Three Beauties, c. 1792–93 Three Beauties Holding Bags of Snacks, c. late 1790s

Three Beauties Holding Bags of Snacks, c. late 1790s

Notes

- Japanese: 富本豊ひな; also spelt 富本豊雛

- Japanese: 難波屋きた

- Kita was sixteen by traditional East-Asian age reckoning; in pre-modern Japan, people were born at the age of one.

- Japanese: 高しまひさ; also spelt 高嶌ひさ or 高島ひさ

- Hisa was seventeen by traditional East-Asian age counting.

- The Three Vinegar Tasters (三聖吸酸図, San-sei Kyūsan Zu)

- Three Beauties (三美人, San Bijin)

- Three Beauties Holding Bags of Snacks (菓子袋を持つ三美人, Kashi-bukuro wo Motsu San Bijin)

References

- Fitzhugh 1979, p. 27.

- Kobayashi 1997, pp. 80–83.

- Kobayashi 1997, p. 91.

- Harris 2011, p. 60.

- Kondō 1956, p. 14.

- Gotō 1975, p. 81.

- Lane 1962, p. 220.

- Davis 2004, p. 122.

- Gotō 1975, pp. 80–81.

- Kobayashi 1997, pp. 87–88.

- Yoshida 1972, p. 240.

- Matsui 2012, p. 62.

- Kondō 2009, p. 131.

- Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai 1980, p. 96.

- Kobayashi 2006, p. 13.

- Yasumura 2013, p. 66; Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai 1980, p. 96.

- Gotō 1975, p. 119.

- Kobayashi 2006, p. 15.

- Kondō 2009, p. 132.

- Yasumura 2013, p. 66.

- Kondō 2009, p. 131; Kobayashi & Ōkubo 1994, p. 35.

- Hickman 1978, p. 76.

- Kondō 2009, pp. 132–133.

- Nichigai Associates 1993, p. 210.

- Kondō 2009, p. 133.

- Kondō 2009, pp. 135–137.

- Kondō 2009, p. 136.

- Kondō 2009, pp. 133–134.

- Kondō 2009, p. 134.

Works cited

- Davis, Julie Nelson (2004). "Artistic Identity and Ukiyo-e Prints: The Representation of Kitagawa Utamaro to the Edo Public". In Takeuchi, Melinda (ed.). The Artist as Professional in Japan. Stanford University Press. pp. 113–151. ISBN 978-0-8047-4355-6.

- Fitzhugh, Elisabeth West (1979). "A Pigment Census of Ukiyo-E Paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art". Ars Orientalis. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan. 11: 27–38. JSTOR 4629295.

- Gotō, Shigeki, ed. (1975). 浮世絵大系 [Ukiyo-e Compendium] (in Japanese). Shueisha. OCLC 703810551.

- Harris, Frederick (2011). Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1098-4.

- Hickman, Manny L. (1978). "当時三美人" [Three Beauties of the Present Day]. 浮世絵聚花 [Ukiyo-e Shūka] (in Japanese). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 3. Shogakukan. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-4-09-652003-1.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi; Ōkubo, Jun'ichi (1994). 浮世絵の鑑賞基礎知識 [Fundamentals of Ukiyo-e Appreciation] (in Japanese). Shibundō. ISBN 978-4-7843-0150-8.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1997). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (2006). 歌麿の美人 [Utamaro's Beauties] (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-652105-2.

- Kondō, Fumito (2009). 歌麿抵抗の美人画 [Utamaro: Bijin-ga in Opposition] (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun Shuppan. ISBN 978-4-02-273257-6.

- Kondō, Ichitarō (1956). Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). Translated by Charles S. Terry. Tuttle. OCLC 613198.

- Lane, Richard (1962). Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. Doubleday. OCLC 185540172. – via Questia (subscription required)

- Matsui, Hideo (2012). 浮世絵の見方 [How to View Ukiyo-e] (in Japanese). Seibundō Shinkōsha. ISBN 978-4-416-81177-1.

- Nichigai Associates (1993). 浮世絵美術全集作品ガイド [Complete Guide to Works of Ukiyo-e Art] (in Japanese). Nichigai Associates. ISBN 978-4-8169-1197-2.

- Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai (1980). Genshoku Ukiyo-e Dai Hyakka Jiten 原色浮世絵大百科事典 [Original Colour Ukiyo-e Encyclopaedia] (in Japanese). 7. Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai. ISBN 978-4-469-09117-5.

- Yasumura, Toshinobu (2013). 浮世絵美人解体新書 [Deconstruction of Ukiyo-e Beauties] (in Japanese). Sekai Bunka-sha. ISBN 978-4-418-13255-3.

- Yoshida, Eiji (1972). 浮世絵事典 定本 [Ukiyo-e Dictionary Revised] (in Japanese). 2 (2 ed.). Gabundō. ISBN 4-87364-005-9.