Kabuki

Kabuki (歌舞伎) is a classical Japanese dance-drama. Kabuki theatre is known for the stylization of its drama, the often-glamorous costumes worn by performers, and for the elaborate kumadori make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki is considered to have begun in 1603 when Izumo no Okuni formed a female dance troupe to perform dances and light sketches in Kyoto, but developed into an all-male theatrical form after females were banned from kabuki theatre in 1629. This form of theatre was perfected in the late 17th and mid-18th century.

In 2005, the "Kabuki theatre" was proclaimed by UNESCO as an intangible heritage possessing outstanding universal value. In 2008, it was inscribed in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[1]

Etymology

The individual kanji, from left to right, mean sing (歌), dance (舞), and skill (伎). Kabuki is therefore sometimes translated as "the art of singing and dancing". These are, however, ateji characters which do not reflect actual etymology. The kanji of skill generally refers to a performer in kabuki theatre.

Since the word kabuki is believed to derive from the verb kabuku, meaning "to lean" or "to be out of the ordinary", kabuki can be interpreted as "avant-garde" or "bizarre" theatre.[2] The expression kabukimono (歌舞伎者) referred originally to those who were bizarrely dressed. It is often translated into English as "strange things" or "the crazy ones", and referred to the style of dress worn by gangs of samurai.

History

1603–1629: Female kabuki

The history of kabuki began in 1603 when Izumo no Okuni, possibly a miko of Izumo-taisha, began performing with a troupe of female dancers a new style of dance drama, on a makeshift stage in the dry bed of the Kamo River in Kyoto.[3] It originated in the 17th century.[4] Japan was under the control of the Tokugawa shogunate, enforced by Tokugawa Ieyasu.[5]

The name of the Edo period derives from the relocation of the Tokugawa regime from its former home in Kyoto to the city of Edo, present-day Tokyo. Female performers played both men and women in comic playlets about ordinary life. The style was immediately popular, and Okuni was asked to perform before the Imperial Court. In the wake of such success, rival troupes quickly formed, and kabuki was born as ensemble dance and drama performed by women—a form very different from its modern incarnation.

Much of the appeal of kabuki in this era was due to the ribald, suggestive themes featured by many troupes; this appeal was further augmented by the fact that many performers were also involved in sex work.[2] For this reason, kabuki was also known as "遊女歌舞妓" (lit., "prostitute kabuki") during this period.

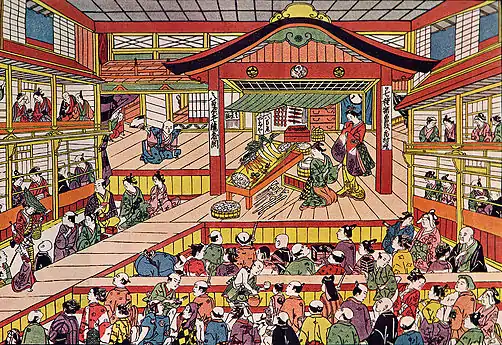

Kabuki became a common form of entertainment in the red-light districts of Japan, especially in Yoshiwara,[6] the registered red-light district in Edo. The widespread appeal of kabuki often meant that a diverse crowd of different social classes often gathered to watch performances, a unique occurrence that happened nowhere else in the city of Edo. Kabuki theatres became well known as a place to both see and be seen in terms of fashion and style, as the audience—commonly comprising a number of socially-low but economically wealthy merchants—typically used a performance as a way to feature the fashion trends.

As an artform, kabuki also provided inventive new forms of entertainment, featuring new music played on the shamisen, clothes and fashion often dramatic in appearance, famous actors and stories often intended to mirror current events. Performances typically lasted from morning until sunset, with surrounding teahouses providing meals, refreshments and place to socialise. The area surrounding kabuki theatres also featured a number of shops selling kabuki souvenirs.

Despite its popularity, the ruling shogunate held unfavorable views of kabuki performances. The crowd at a kabuki performance often mixed different social classes, and the social peacocking of the merchant classes, who controlled much of Japan's economy at the time, were perceived to have entrenched upon the standing of the samurai classes, both in appearance and often wealth. In an effort to clamp down on kabuki's popularity, women's kabuki, known as onna-kabuki, was banned in 1629 for being too erotic.[7] Following this ban, young boys began performing in wakashū-kabuki, which was also soon banned.[7] Kabuki switched to adult male actors, called yaro-kabuki, in the mid-1600s.[8] Adult male actors, however, continued to play both female and male characters, and kabuki retained its popularity, remaining a key aspect of the Edo period urban lifestyle.

Although kabuki was performed widely across Japan, the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za theatres became the most widely known and popular kabuki theatres, where some of the most successful kabuki performances were and still are held.[5]

1629–1673: Transition to yarō-kabuki

During the time period of 1628–1673, the modern version of all-male kabuki actors, a style of kabuki known as yarō-kabuki (lit., "young man kabuki"), was established, following the ban on women and young boys. Cross-dressing male actors, known as "onnagata" (lit., "female role") or "oyama" took over previously female- or wakashu-acted roles. Young (adolescent) men were still preferred for women's roles due to their less obviously masculine appearance and the higher pitch of their voices. The roles of adolescent men in kabuki, known as wakashu, were also played by young men, often selected for their attractiveness; this became a common practice, and wakashu were often presented in an erotic context.[9]

The focus of kabuki performances also increasingly began to emphasise drama alongside dance. However, the ribald nature of kabuki performances continued, with male actors also engaging in sex work for both female and male customers. Audiences frequently became rowdy, and brawls occasionally broke out, sometimes over the favors of a particularly popular or handsome actor, leading the shogunate to ban first onnagata and then wakashū roles for a short period of time; both bans were rescinded by 1652.[10]

1673–1841: Genroku period kabuki

During the Genroku period, kabuki thrived, with the structure of kabuki plays formalising into the structure they are performed in today, alongside many other elements which eventually came to be recognised as a key aspect of kabuki tradition, such as conventional character tropes. Kabuki theater and ningyō jōruri, an elaborate form of puppet theater later known as bunraku, became closely associated with each other, mutually influencing the other's further development.

The famous playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon, one of the first professional kabuki playwrights, produced several influential works during this time, though the piece usually acknowledged as his most significant, Sonezaki Shinjū (The Love Suicides at Sonezaki), was originally written for bunraku. Like many bunraku plays, it was adapted for kabuki, eventually becoming popular enough to reportedly inspire a number of real-life "copycat" suicides, and leading to a government ban on shinju mono (plays about love suicides) in 1723.

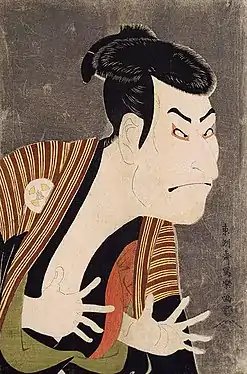

Also during the Genroku period was the development of the mie style of posing, credited to kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjūrō I,[11] alongside the development of the mask-like kumadori makeup worn by kabuki actors in some plays.[12]

In the mid-18th century, kabuki fell out of favor for a time, with bunraku taking its place as the premier form of stage entertainment among the lower social classes. This occurred partly because of the emergence of several skilled bunraku playwrights in that time. Little of note would occur in the further development of kabuki until the end of the century, when it began to re-emerge in popularity.

1842–1868: Saruwaka-chō kabuki

_-85.282.6a-_Hokushu.jpg.webp)

In the 1840s, repeated periods of drought led to a series of fires affecting Edo, with kabuki theatres—traditionally made of wood—frequently burning down, forcing many to relocate. When the area that housed the Nakamura-za was completely destroyed in 1841, the shōgun refused to allow the theatre to be rebuilt, saying that it was against fire code.[8]

The shogunate, mostly disapproving of the socialisation and trade that occurred in kabuki theatres between merchants, actors and sex workers, took advantage of the fire crisis in the following year, forcing the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za out of the city limits and into Asakusa, a northern suburb of Edo. Actors, stagehands, and others associated with the performances were also forced to move in lieu of the death of their livelihood; despite the move of everyone involved in kabuki performance, and many in the surrounding areas, to the new location of the theatres, the inconvenience of the distance led to a reduction in attendance.[5] These factors, along with strict regulations, pushed much of kabuki "underground" in Edo, with performances changing locations to avoid the authorities.

The theatres' new location was called Saruwaka-chō, or Saruwaka-machi; the last thirty years of the Tokugawa shogunate's rule is often referred to as the "Saruwaka-machi period", and is well known for having produced some of the most exaggerated kabuki in Japanese history.[5]

Saruwaka-machi became the new theatre district for the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za theatres. The district was located on the main street of Asakusa, which ran through the middle of the small city. The street was renamed after Saruwaka Kanzaburo, who initiated Edo kabuki in the Nakamura-za in 1624.[5]

European artists began noticing Japanese theatrical performances and artwork, and many artists, such as Claude Monet, were inspired by Japanese woodblock prints. This Western interest prompted Japanese artists to increase their depictions of daily life, including the depiction of theatres, brothels, main streets and so on. One artist, Utagawa Hiroshige, produced a series of prints based on Saruwaka from the Saruwaka-machi period in Asakusa.[5]

Despite the revival of kabuki in another location, the relocation diminished the tradition's most abundant inspirations for costuming, make-up, and storylines. Ichikawa Kodanji IV was considered one of the most active and successful actors during the Saruwaka-machi period. Deemed unattractive, he mainly performed buyō, or dancing, in dramas written by Kawatake Mokuami, who also wrote during the Meiji era to follow.[5] Kawatake Mokuami commonly wrote plays that depicted the common lives of the people of Edo. He introduced shichigo-cho (seven-and-five syllable meter) dialogue and music such as kiyomoto.[5] His kabuki performances became quite popular once the Saruwaka-machi period ended and theatre returned to Edo; many of his works are still performed.

In 1868, the Tokugawa ceased to exist, with the restoration of the Emperor. Emperor Meiji was restored to power and moved from Kyoto to the new capital of Edo, or Tokyo, beginning the Meiji period.[8] Kabuki once again returned to the pleasure quarters of Edo, and throughout the Meiji period became increasingly more radical, as modern styles of kabuki plays and performances emerged. Playwrights experimented with the introduction of new genres to kabuki, and introduced twists on traditional stories.

Post-Meiji period kabuki

Beginning in 1868, enormous cultural changes, such as the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate, the elimination of the samurai class, and the opening of Japan to the West, helped to spark kabuki's re-emergence. Both actors and playwrights strove to improve the reputation of kabuki in the face of new foreign influence and amongst the upper classes, partially through adapting traditional styles to modern tastes. This endeavour would prove successful, with the Emperor sponsoring a kabuki performance on 21 April 1887.[13]

After World War II, the occupying forces briefly banned kabuki, which had formed a strong base of support for Japan's war efforts since 1931;[14] however, by 1947 the ban had been rescinded.[15]

Post-war to modern day kabuki

The ensuing period of occupation following World War II posited a difficult time for kabuki; besides the war's physical impact and devastation upon the country, some schools of thought chose to reject both the styles and artforms of pre-war Japan, kabuki amongst them.[16] Director Tetsuji Takechi's popular and innovative productions of kabuki classics at this time are credited with sparking new interest in kabuki in the Kansai region.[17] Of the many popular young stars who performed with the Takechi Kabuki, Nakamura Ganjiro III (b. 1931) was the leading figure, first known as Nakamura Senjaku before taking his current name. It was this period of kabuki in Osaka that became known as the "Age of Senjaku" in his honor.[17]

Today, kabuki is the most popular of the traditional styles of Japanese drama, with its star actors often appearing in television or film roles.[18] Well-known onnagata actor Bandō Tamasaburō V has appeared in several non-kabuki plays and movies, often in the role of a woman.

Kabuki also appears in works of Japanese popular culture such as anime. In addition to the handful of major theatres in Tokyo and Kyoto, there are many smaller theatres in Osaka and throughout the countryside.[19] The Ōshika Kabuki (大鹿歌舞伎) troupe, based in Ōshika, Nagano Prefecture, is one example.[20]

Some local kabuki troupes today use female actors in onnagata roles. The Ichikawa Shōjo Kabuki Gekidan, an all-female troupe, debuted in 1953 to significant acclaim, though the majority of kabuki troupes have remained entirely-male.[21]

The introduction of earphone guides in 1975,[22] including an English version in 1982,[22] helped broaden the artform's appeal. As a result, in 1991 the Kabuki-za, one of Tokyo's best known kabuki theaters, began year-round performances[22] and, in 2005, began marketing kabuki cinema films.[23] Kabuki troupes regularly tour Asia,[24] Europe[25] and America,[26] and there have been several kabuki-themed productions of Western plays such as those of Shakespeare. Western playwrights and novelists have also experimented with kabuki themes, an example of which is Gerald Vizenor's Hiroshima Bugi (2004). Writer Yukio Mishima pioneered and popularised the use of kabuki in modern settings and revived other traditional arts, such as Noh, adapting them to modern contexts. There have even been kabuki troupes established in countries outside Japan. For instance, in Australia, the Za Kabuki troupe at the Australian National University has performed a kabuki drama each year since 1976,[27] the longest regular kabuki performance outside Japan.[28]

In November 2002, a statue was erected in honor of kabuki's founder, Izumo no Okuni and to commemorate 400 years of kabuki's existence.[29] Diagonally across from the Minami-za,[30] the last remaining kabuki theater in Kyoto,[30] it stands at the east end of a bridge (Shijō Ōhashi)[30] crossing the Kamo River in Kyoto.

Kabuki was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2005.[31][32]

Super Kabuki

While still maintaining most of the historical practices of Kabuki, Ichikawa En-ou (市川猿翁)[33] aimed to broaden its appeal by creating a new genre of Kabuki productions called "Super Kabuki" (スーパー歌舞伎). With Yamoto Takeru (ヤマトタケル) as the first Super Kabuki production to premiere in 1986, remakes of traditional plays and new contemporary creations have been brought to local theaters throughout the country, including anime-based productions such as Naruto or One Piece starting from 2014.

Super Kabuki has sparked controversy within the Japanese population regarding the extent of modification of the traditional art form.[34] Some say that it has lost its 400-year history, while others consider the adaptations necessary for contemporary relevance. Regardless, since incorporating more advanced technology in the new stage sets, costumes, and lighting, Super Kabuki has regained interest from the young demographic.

Elements

Stage design

The kabuki stage features a projection called a hanamichi (花道) (lit., "flower path"), a walkway which extends into the audience and via which dramatic entrances and exits are made. Okuni also performed on a hanamichi stage with her entourage. The stage is used not only as a walkway or path to get to and from the main stage, but important scenes are also played on the stage.

Kabuki stages and theaters have steadily become more technologically sophisticated, and innovations including revolving stages and trap doors were introduced during the 18th century. A driving force has been the desire to manifest one frequent theme of kabuki theater, that of the sudden, dramatic revelation or transformation.[35] A number of stage tricks, including actors' rapid appearance and disappearance, employ these innovations. The term keren (外連), often translated as playing to the gallery, is sometimes used as a catch-all for these tricks. The hanamichi, and several innovations including revolving stage, seri and chunori have all contributed to kabuki. The hanamichi creates depth and both seri and chunori provide a vertical dimension.

Mawari-butai (revolving stage) developed in the Kyōhō era (1716–1735). The trick was originally accomplished by the on-stage pushing of a round, wheeled platform. Later a circular platform was embedded in the stage with wheels beneath it facilitating movement. The kuraten ("darkened revolve") technique involves lowering the stage lights during this transition. More commonly the lights are left on for akaten ("lighted revolve"), sometimes simultaneously performing the transitioning scenes for dramatic effect. This stage was first built in Japan in the early eighteenth century.

Seri refers to the stage "traps" that have been commonly employed in kabuki since the middle of the 18th century. These traps raise and lower actors or sets to the stage. Seridashi or seriage refers to trap(s) moving upward and serisage or serioroshi to traps descending. This technique is often used to lift an entire scene at once.

.JPG.webp)

Chūnori (riding in mid-air) is a technique, which appeared toward the middle of the 19th century, by which an actor's costume is attached to wires and he is made to "fly" over the stage or certain parts of the auditorium. This is similar to the wire trick in the stage musical Peter Pan, in which Peter launches himself into the air. It is still one of the most popular keren (visual tricks) in kabuki today; major kabuki theaters, such as the National Theatre, Kabukiza and Minamiza, are all equipped with chūnori installations.[36]

Scenery changes are sometimes made mid-scene, while the actors remain on stage and the curtain stays open. This is sometimes accomplished by using a Hiki Dōgu, or "small wagon stage". This technique originated at the beginning of the 18th century, where scenery or actors move on or off stage on a wheeled platform. Also common are stagehands rushing onto the stage adding and removing props, backdrops and other scenery; these kuroko (黒子) are always dressed entirely in black and are traditionally considered invisible. Stagehands also assist in a variety of quick costume changes known as hayagawari ("quick change technique"). When a character's true nature is suddenly revealed, the devices of hikinuki and bukkaeri are often used. This involves layering one costume over another and having a stagehand pull the outer one off in front of the audience.

The curtain that shields the stage before the performance and during the breaks is in the traditional colours of black, red and green, in various order, or white instead of green, vertical stripes. The curtain consists of one piece and is pulled back to one side by a staff member by hand.

An additional outer curtain called doncho was not introduced until the Meiji era following the introduction of western influence. These are more ornate in their appearance and are woven. They depict the season in which the performance is taking place, often designed by renowned Nihonga artists.[37]

Appearances

Since feudal laws in 17th-century Japan prohibited replicating the looks of samurai or nobility and the use of luxurious fabrics, the kabuki costumes were groundbreaking new designs to the general public, even setting trends that still exist today.

Although the earliest kabuki costumes had not been preserved, separate otoko and onnagata kabuki costumes today are made based on written records called ukiyo-e and in collaboration with those whose families have been in the kabuki industry for generations.[38] The kimonos the actors wear for their costumes are typically made with vibrant colors and multiple layers. To correspond to Japanese beauty standards back then, otokos and onnagatas both wear hakamas, which are pleated trousers, and paddings at the midriff to create a rectangular-shaped torso.

Kabuki makeup provides an element of style easily recognizable even by those unfamiliar with the art form. Rice powder is used to create the white oshiroi base for the characteristic stage makeup, and kumadori enhances or exaggerates facial lines to produce dramatic animal or supernatural masks. The color of the kumadori is an expression of the character's nature: red lines are used to indicate passion, heroism, righteousness, and other positive traits; blue or black, villainy, jealousy, and other negative traits; green, the supernatural; and purple, nobility.[12]

Another special feature of kabuki costumes is the katsura, or the wig.[38] Each actor has a different katsura for every role and has a copper base that is custom-made to fit his head perfectly. Most of the time, real human hair is hand-sewn onto a silk fabric, but some types of katsuras require other imported materials such as yak hair or horse hair.

Performance

The three main categories of kabuki play are jidaimono (時代物, historical, or pre-Sengoku period stories), sewamono (世話物, domestic, or post-Sengoku stories) and shosagoto (所作事, dance pieces).[39]

Jidaimono, or history plays, are set within the context of major events in Japanese history. Strict censorship laws during the Edo period prohibited the representation of contemporary events and particularly prohibited criticising the shogunate or casting it in a bad light, although enforcement varied greatly over the years. Many shows were set in the context of the Genpei War of the 1180s, the Nanboku-chō Wars of the 1330s, or other historical events. Frustrating the censors, many shows used these historical settings as metaphors for contemporary events. Kanadehon Chūshingura, one of the most famous plays in the kabuki repertoire, serves as an excellent example; it is ostensibly set in the 1330s, though it actually depicts the contemporary (18th century) affair of the revenge of the 47 rōnin.

Unlike jidaimono which generally focused upon the samurai class, sewamono focused primarily upon commoners, namely townspeople and peasants. Often referred to as "domestic plays" in English, sewamono generally related to themes of family drama and romance. Some of the most famous sewamono are the love suicide plays, adapted from works by the bunraku playwright Chikamatsu; these center on romantic couples who cannot be together in life due to various circumstances and who therefore decide to be together in death instead. Many if not most sewamono contain significant elements of this theme of societal pressures and limitations.

Shosagoto pieces place their emphasis on dance, which may be performed with or without dialogue, where dance can be used to convey emotion, character and plot.[40] Quick costume change techniques may sometimes be employed in such pieces. Notable examples include Musume Dōjōji and Renjishi. Nagauta musicians may be seated in rows on stepped platforms behind the dancers.[41]

Important elements of kabuki include the mie (見得), in which the actor holds a picturesque pose to establish his character.[35] At this point his house name (yagō, 屋号) is sometimes heard in loud shout (kakegoe, 掛け声) from an expert audience member, serving both to express and enhance the audience's appreciation of the actor's achievement. An even greater compliment can be paid by shouting the name of the actor's father.

The main actor has to convey a wide variety of emotions between a fallen, drunkard person and someone who in reality is quite different since he is only faking his weakness, for example in the character of Yuranosuke in Chūshingura. This is called hara-gei or "belly acting", which means he has to perform from within to change characters. It is technically difficult to perform and takes a long time to learn, but once mastered the audience takes up on the actor's emotion.

Emotions are also expressed through the colours of the costumes, a key element in kabuki. Gaudy and strong colours can convey foolish or joyful emotions, whereas severe or muted colours convey seriousness and focus.

Play structure and performance style

Kabuki, like other forms of drama traditionally performed in Japan, was—and sometimes still is—performed in full-day programmes, with one play comprising a number of acts spanning the entire day. However, these plays—particularly sewamono—were commonly sequenced with acts from other plays in order to produce a full-day programme, as the individual acts in a kabuki play commonly functioned as stand-alone performances in and of themselves. Sewamono plays, in contrast, were generally not sequenced with acts from other plays, and genuinely would take the entire day to perform.

The structure of a full-day performance was derived largely from the conventions of both bunraku and Noh theatre. Chief amongst these was the concept of jo-ha-kyū (序破急), a pacing convention in theatre stating that the action of a play should start slow, speed up, and end quickly. The concept, elaborated on at length by master Noh playwright Zeami, governs not only the actions of the actors, but also the structure of the play, as well as the structure of scenes and plays within a day-long programme.

Nearly every full-length play occupies five acts. The first corresponds to jo, an auspicious and slow opening which introduces the audience to the characters and the plot. The next three acts correspond to ha, where events speed up, culminating almost always in a great moment of drama or tragedy in the third act, and possibly a battle in the second or fourth acts. The final act, corresponding to kyū, is almost always short, providing a quick and satisfying conclusion.[42]

While many plays were written solely for kabuki, many others were taken from jōruri plays, Noh plays, folklore, or other performing traditions such as the oral tradition of the Tale of the Heike. While jōruri plays tend to have serious, emotionally dramatic, and organised plots, plays written specifically for kabuki generally have looser, more humorous plots.[43]

One crucial difference between jōruri and kabuki is a difference in storytelling focus; whereas jōruri focuses on the story and on the chanter who recites it, kabuki has a greater focus on the actors themselves. A jōruri play may sacrifice the details of sets, puppets, or action in favor of the chanter, while kabuki is known to sacrifice drama and even the plot to highlight an actor's talents. It was not uncommon in kabuki to insert or remove individual scenes from a day's schedule in order to cater to an individual actor—either scenes he was famed for, or that featured him, would be inserted into a program without regard to plot continuity.[43] Certain plays were also performed uncommonly as they required an actor to be proficient in a number of instruments, which would be played live onstage, a skill that few actors possessed.[44]

Kabuki traditions in Edo and the Kyoto-Osaka region (Kamigata) differed; throughout the Edo period, Edo kabuki was defined by its extravagance, both in the appearance of its actors, their costumes, stage tricks and bold mie poses. In contrast, Kamigata kabuki focused on natural and realistic styles of acting. Only towards the end of the Edo period did the two styles begin to merge to any significant degree.[45] Before this time, actors from different regions often failed to adjust their acting styles when performing elsewhere, leading to unsuccessful performance tours outside of their usual region of performance.

Famous plays

While there are many famous plays known today, many of the most famous were written in the mid-Edo period, and were originally written for bunraku theatre.

- Kanadehon Chūshingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) is the famous story of the Forty-seven rōnin, led by Oishi Kuranosuke, who exact revenge on their enemy before committing suicide upon the death of their master, Lord Takuminokami of the Asano clan.[46] This story is one of the most popular traditional tales in Japan, and is based on a famous episode in 18th-century Japanese history.

- Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura (Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees) follows Minamoto no Yoshitsune as he flees from agents of his brother Yoritomo. Three Taira generals supposed killed in the Genpei War figure prominently, as their deaths ensure a complete end to the war and the arrival of peace, as does a kitsune named Genkurō.[47]

- Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy) is based on the life of famed scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), who is exiled from Kyoto, and upon his death causes a number of calamities in the capital. He is then deified, as Tenjin, kami ("divine spirit") of scholarship, and worshipped in order to propitiate his angry spirit.[46]

Actors

.JPG.webp)

Every kabuki actor has a stage name, which is different from the name they were born with. These stage names, most often those of the actor's father, grandfather, or teacher, are passed down between generations of actors' lineages, and hold great honor and importance. Many names are associated with certain roles or acting styles, and the new possessor of each name must live up to these expectations; there is the feeling almost of the actor not only taking a name, but embodying the spirit, style, or skill of each actor to previously hold that name. Many actors will go through at least three names over the course of their career.

Shūmei (襲名) (lit., name succession) are grand naming ceremonies held in kabuki theatres in front of the audience. Most often, a number of actors will participate in a single ceremony, taking on new stage-names. Their participation in a shūmei represents their passage into a new chapter of their performing careers.

Kabuki actors are typically part of a school of acting, or are associated with a particular theatre.

Major theatres

See also

- Theatre of Japan

- Kanteiryū, a lettering style invented to advertise kabuki and other theatrical performances

- Kyōgen, a traditional form of Japanese comic theatre that influenced the development of kabuki

- Oshiguma, an imprint of the face make-up of kabuki actors, as artwork and souvenir

- Noh, a traditional form of Japanese theatre

- Bunraku, a traditional Japanese puppet theatre from whose scripts many kabuki plays were adapted

- Famous kabuki actor lineages, such as:

- Sgt. Kabukiman NYPD, a 1991 comedic superhero film directed by Lloyd Kaufman and Michael Herz and distributed by Troma Entertainment.

- Kabukibu!, a light novel, manga, and anime series about a boy who loves kabuki

- Kathakali

- Jingju

- Yakshagana

- Balinese dance

Notes

- https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/kabuki-theatre-00163

- "Kabuki" in Frederic, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- "Okuni | Kabuki dancer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Haar 1971, p. 83

- Masato 2007

- Flynn, Patricia. "Visions of People: The Influences of Japanese Prints Ukiyo-e Upon Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century French Art". Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Lombard, Frank Alanson (1928). An Outline History of the Japanese Drama. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD. pp. 287–295. ISBN 978-1-138-91983-9.

- Ernst 1956, pp. 10–12

- Leupp 1997, pp. 91–92

- Leupp 1997, p. 92

- "Mie". Kabuki Jiten. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- Kincaid, Zoe (1925). Kabuki: The Popular Stage of Japan. London: MacMillan and Co. pp21–22.

- Shōriya, Asagoro. Kabuki Chronology of the 19th century at Kabuki21.com (Retrieved 18 December 2006.)

- Brandon 2009

- Takemae, Eiji (2002) [1983]. The Allied Occupation of Japan. Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann (translators and adapters). New York & London: Continuum. pp. 390–391. ISBN 0-8264-6247-2.

- Kominz, Laurence (1997). The Stars Who Created Kabuki; Their Lives, Loves and Legacy. Tokyo, New York, London: Kodansha International. p. 232. ISBN 4-7700-1868-1.

- Toita, Yasuji (1970). "Zenshin-za Innovations". Kabuki: The Popular Theater. Performing Arts of Japan: II. Don Kenny (trans.). New York & Tokyo: Walker/Weatherhill. p. 213. ISBN 0-8027-2424-8.

- Shōriya, Asagoro. Contemporary Actors at Kabuki21.com. (Retrieved 18 December 2006.)

- "Kabuki Theaters". Kabuki21.com. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Ōshika Kabuki". Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Edelson, Loren. Playing for the Majors and the Minors: Ichikawa Girls' Kabuki on the Postwar Stage. In: Leiter, Samuel (ed). Rising from the Flames: The Rebirth of Theater in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. pp. 75–85.

- Martin, Alex, "Kabuki going strong, 400 years on", Japan Times, 28 December 2010, p. 3,

- Martin, Alex, "Kabuki going strong, 400 years on", Japan Times, 28 December 2010, p. 3, retrieved on 29 December 2010.

- "Kabuki Tours in Asia". Kabuki21.com. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Kabuki Tours in Europe". Kabuki21.com. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Kabuki Tours in North And South America". Kabuki21.com. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- Za Kabuki Troupe, "Za Kabuki 2012: Who We Are." Last modified 2012. Accessed 28 April 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/zakabuki2010/who-we-are

- Negishi, K, and M Tomoeda. "ANU Za Kabuki." Monsoon, 2010, 26.

- Sign (in English) for Izumo no Okuni's statue in Kyoto

- Lonely Planet Kyoto, 2012, page 169

- "2001~2100". Kabuki21.com. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "UNESCO Culture Sector – Intangible Heritage – 2003 Convention". Unesco.org. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "市川猿翁 2 | 歌舞伎俳優名鑑 現在の俳優篇" (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "ワンピース・NARUTO・初音ミク 現代の歌舞伎は「超歌舞伎」へ". ワゴコロ (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Scott 1955, pp. 55–56

- Ukon Ichikawa as Genkurō Kitsune flying over audience Archived 10 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine in the July 2005 National Theatre production of Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Macintosh, Fiona (30 July 2015), "dance reception", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.7006, ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5, retrieved 19 October 2020

- "Kabuki « MIT Global Shakespeares". Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Pronko, Leonard C. (12 February 2015). Samuel L. Leiter (ed.). A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance: History and Performance. p. 248. ISBN 9781315706832.

- Leiter, Samuel L. (16 January 2006). Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre. p. 115. ISBN 9780810865143.

- Quinn, Shelley Fenno. "How to write a Noh play—Zeami's Sandō. Monumenta Nipponica, vol 48, issue 1 (Spring 1993). pp53–88.

- Toita, Yasuji (1970). Kabuki: The Popular Theater. New York: Weatherhill. pp 6–8.

- Photographic Kabuki Kaleidoscope, I. Somegoro and K. Rinko, 2017. Shogakukan.

- Thornbury, Barbara E. "Sukeroku's Double Identity: The Dramatic Structure of Edo Kabuki". Japanese Studies 6 (1982). Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. 13

- Miyake, Shutarō (1971). "Kabuki Drama". Tokyo: Japan Travel Bureau.

- Jones, Stanleigh H. Jr. (trans.)(1993). "Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees." New York: Columbia University Press.

References

- Brandon, James R. (2009). Kabuki's Forgotten War: 1931–1945. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3200-1.

- Ronald Cavaye (1993). Kabuki: A Pocket Guide. USA and Japan: Charles E. Tuttle,

- Ronald Cavaye, Paul Griffith and Akihiko Senda (2004). A Guide to the Japanese Stage. Japan: Kodansha International.

- Ernst, E. (1956). The Kabuki Theatre. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A. C. (1955). The Kabuki Theatre of Japan. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Senelick, L. (2000). The Changing Room: Sex, Drag, and Theatre. London: Routledge.

- Facts JPN-kabuki. 25 November 2007 <https://web.archive.org/web/20070606160340/http://inic.utexas.edu/asnic/countries/japan/kabuki.html>.

- Japanese Culture. 25 November 2007 <http://japan-zone.com/culture/kabuki.shtml>.

- Kabuki. 25 November 2007 <http://japan-guide.com/e/e2090.html>

- Kabuki. Ed. Shoriya Aragoro. 9 September 1999. 25 November 2007 <http://www.kabuki21.com/>

- Haar, Francils (1971). Japanese Theatre in Highlight: A Pictorial Commentary. Westport: Greenwood P. p. 83.

- Masato, Takaba (2007). "History of Kabuki: Birth of Saruwaka-machi". Watanabe Norihiko. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

Further reading

- Kawatake, Toshio (2006). Kabuki: Baroque Fusion of the Arts. Tokyo: I-House Press.

- Matsui, Kesako (2016). Kabuki, a Mirror of Japan: Ten Plays that Offer a Glimpse into Evolving Sensibilities. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kabuki. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kabuki actors. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kabuki theaters. |

- Kabuki Web—Shochiku Official Kabuki Website in English

- Earphone Guide—The English language Earphone Guide

- Kabuki 21—All about Japan's traditional Theatre Art of Kabuki: The art, the plays, the great stars of today, the legends of the past, the theaters, the history, the glossary, the traditions, the heroes and the derivatives.

- National Diet Library: photograph of Kabuki-za in Kyobashi-ku, Kobiki-cho, Tokyo (1900); Kakuki-za (1901); Kakuki-za (1909); Kabuki-za (1911); Kabuki-za (1912); Kakuki-za (1915)

- Kabuki prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861)

- Japan Mint: Kabuki Coin Set

- Audio recording of the kabuki play Narukami by Ichikawa Danjūrō I at LostPlays.com

- 1969 'Camera Three' program on Kabuki, (audio only; with Faubion Bowers et al.)

- Collection: "Kabuki Images" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- "Kabuki Performance and Expression in Japanese Prints" exhibition at the Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Missouri