Tiberius

Tiberius Caesar Augustus (/taɪˈbɪəriəs/ ty-BEER-ee-əs; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor, reigning from AD 14 to 37. He succeeded his stepfather, Augustus.

| Tiberius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

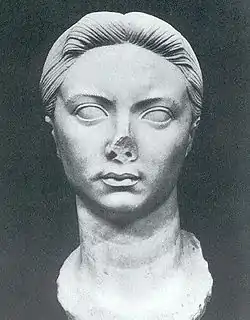

.jpg.webp) Bust of Tiberius at the Romano-Germanic Museum in Cologne | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 18 September 14 – 16 March 37 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Augustus | ||||||||

| Successor | Caligula | ||||||||

| Born | 16 November 42 BC Rome, Italy, Roman Republic | ||||||||

| Died | 16 March AD 37 (aged 77) Misenum, Italy, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse |

| ||||||||

| Issue more... |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | ||||||||

| Father |

| ||||||||

| Mother | Livia | ||||||||

Tiberius was one of Rome's greatest generals: his conquests of Pannonia, Dalmatia, Raetia, and (temporarily) parts of Germania laid the foundations for the northern frontier. Even so, he came to be remembered as a dark, reclusive and somber ruler who never really desired to be emperor; Pliny the Elder called him "the gloomiest of men".[1] After the death of his son Drusus Julius Caesar in AD 23, Tiberius became more reclusive and aloof. During Tiberius' reign, Jews had become more prominent in Rome, and Jewish and Gentile followers of Jesus Christ began proselytizing to Roman citizens, increasing long-simmering resentments. In 26 AD he removed himself from Rome and left administration largely in the hands of his unscrupulous Praetorian prefects Sejanus and Naevius Sutorius Macro. When Tiberius died, he was succeeded by his grand-nephew and adopted grandson, Caligula.[2]

Early life (42–6 BC)

| Roman imperial dynasties | |||

| Julio-Claudian dynasty | |||

.png.webp) Aureus of Tiberius | |||

| Chronology | |||

| Augustus | 27 BC – AD 14 | ||

| Tiberius | AD 14–37 | ||

| Caligula | AD 37–41 | ||

| Claudius | AD 41–54 | ||

| Nero | AD 54–68 | ||

| Succession | |||

| Preceded by Roman Republic |

Followed by Year of the Four Emperors | ||

Background

Tiberius was born in Rome on 16 November 42 BC to Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla.[3][4] In 39 BC, his mother divorced his biological father and, though again pregnant by Tiberius Nero, married Octavian. In 38 BC his brother, Nero Claudius Drusus, was born.[5]

Little is recorded of Tiberius' early life. In 32 BC, Tiberius, at the age of nine, delivered the eulogy for his biological father at the rostra.[6] In 29 BC, he rode in the triumphal chariot along with his adoptive father Octavian in celebration of the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium.[6]

In 23 BC, Emperor Augustus became gravely ill, and his possible death threatened to plunge the Roman world into chaos again. Historians generally agree that it is during this time that the question of Augustus' heir became most acute, and while Augustus had seemed to indicate that Agrippa and Marcellus would carry on his position in the event of his death, the ambiguity of succession became Augustus' chief problem.[7]

In response, a series of potential heirs seem to have been selected, among them Tiberius and his brother Drusus. In 24 BC, at the age of seventeen, Tiberius entered politics under Augustus' direction, receiving the position of quaestor,[8] and was granted the right to stand for election as praetor and consul five years in advance of the age required by law.[9] Similar provisions were made for Drusus.[10]

Civil and military career

Shortly thereafter Tiberius began appearing in court as an advocate,[11] and it was presumably at this time that his interest in Greek rhetoric began. In 20 BC, Tiberius was sent east under Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa.[12] The Parthian Empire had captured the standards of the legions under the command of Marcus Licinius Crassus (53 BC) (at the Battle of Carrhae), Decidius Saxa (40 BC), and Mark Antony (36 BC).[9]

After a year of negotiation, Tiberius led a sizable force into Armenia, presumably to establish it as a Roman client state and end the threat it posed on the Roman-Parthian border. Augustus was able to reach a compromise whereby the standards were returned, and Armenia remained a neutral territory between the two powers.[9]

Tiberius married Vipsania Agrippina, the daughter of Augustus' close friend and greatest general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa.[13] He was appointed to the position of praetor, and was sent with his legions to assist his brother Drusus in campaigns in the west. While Drusus focused his forces in Gallia Narbonensis and along the German frontier, Tiberius combated the tribes in the Alps and within Transalpine Gaul, conquering Raetia. In 15 BC he discovered the sources of the Danube, and soon afterward the bend of the middle course.[14] Returning to Rome in 13 BC, Tiberius was appointed as consul, and around this same time his son, Drusus Julius Caesar, was born.[15]

Agrippa's death in 12 BC elevated Tiberius and Drusus with respect to the succession. At Augustus' request in 11 BC, Tiberius divorced Vipsania and married Julia the Elder, Augustus' daughter and Agrippa's widow.[2][13] Tiberius was very reluctant to do this, as Julia had made advances to him when she was married and Tiberius was happily married. His new marriage with Julia was happy at first, but turned sour.[13]

Reportedly, Tiberius once ran into Vipsania again, and proceeded to follow her home crying and begging forgiveness;[13] soon afterwards, Tiberius met with Augustus, and steps were taken to ensure that Tiberius and Vipsania would never meet again.[16] Tiberius continued to be elevated by Augustus, and after Agrippa's death and his brother Drusus' death in 9 BC, seemed the clear candidate for succession. As such, in 12 BC he received military commissions in Pannonia and Germania, both areas highly volatile and of key importance to Augustan policy.

In 6 BC, Tiberius launched a pincer movement against the Marcomanni. Setting out northwest from Carnuntum on the Danube with four legions, Tiberius passed through Quadi territory in order to invade Marcomanni territory from the east. Meanwhile, general Gaius Sentius Saturninus would depart east from Moguntiacum on the Rhine with two or three legions, pass through newly annexed Hermunduri territory, and attack the Marcomanni from the west. The campaign was a resounding success, but Tiberius could not subjugate the Marcomanni because he was soon summoned to the Rhine frontier to protect Rome's new conquests in Germania.

He returned to Rome and was consul for a second time in 7 BC, and in 6 BC was granted tribunician power (tribunicia potestas) and control in the East,[17] all of which mirrored positions that Agrippa had previously held. However, despite these successes and despite his advancement, Tiberius was not happy.[18]

Midlife (6 BC – 14 AD)

Retirement to Rhodes (6 BC)

In 6 BC, on the verge of accepting command in the East and becoming the second-most powerful man in Rome, Tiberius suddenly announced his withdrawal from politics and retired to Rhodes.[19] The precise motives for Tiberius's withdrawal are unclear.[20] Historians have speculated a connection with the fact that Augustus had adopted Julia's sons by Agrippa, Gaius and Lucius, and seemed to be moving them along the same political path that both Tiberius and Drusus had trodden.[21]

Tiberius' move thus seemed to be an interim solution: he would hold power only until his stepsons would come of age, and then be swept aside. The promiscuous, and very public behavior of his unhappily married wife, Julia,[22] may have also played a part.[17] Indeed, Tacitus calls it Tiberius' intima causa, his innermost reason for departing for Rhodes and seems to ascribe the entire move to a hatred of Julia and a longing for Vipsania.[23] Tiberius had found himself married to a woman he loathed, who publicly humiliated him with nighttime escapades in the Roman Forum, and forbidden to see the woman he had loved.[24]

Whatever Tiberius' motives, the withdrawal was almost disastrous for Augustus' succession plans. Gaius and Lucius were still in their early teens, and Augustus, now 57 years old, had no immediate successor. There was no longer a guarantee of a peaceful transfer of power after Augustus' death, nor a guarantee that his family, and therefore his family's allies, would continue to hold power should the position of Princeps survive.[24]

Somewhat apocryphal stories tell of Augustus pleading with Tiberius to stay, even going so far as to stage a serious illness.[24] Tiberius' response was to anchor off the shore of Ostia until word came that Augustus had survived, then sailing straightway for Rhodes.[25] Tiberius reportedly regretted his departure and requested to return to Rome several times, but each time Augustus refused his requests.[26]

Heir to Augustus

With Tiberius' departure, succession rested solely on Augustus' two young grandsons, Lucius and Gaius Caesar. The situation became more precarious in AD 2 with the death of Lucius. Augustus, with perhaps some pressure from Livia, allowed Tiberius to return to Rome as a private citizen and nothing more.[27] In AD 4, Gaius was killed in Armenia, and Augustus had no other choice but to turn to Tiberius.[28][29]

The death of Gaius in AD 4 initiated a flurry of activity in the household of Augustus. Tiberius was adopted as full son and heir, and in turn he was required to adopt his nephew Germanicus, the son of his brother Drusus and Augustus' niece Antonia Minor.[28][30] Along with his adoption, Tiberius received tribunician power as well as a share of Augustus' maius imperium, something that even Marcus Agrippa may never have had.[31]

In AD 7, Agrippa Postumus, a younger brother of Gaius and Lucius, was disowned by Augustus and banished to the island of Pianosa, to live in solitary confinement.[29][32] Thus, when in AD 13, the powers held by Tiberius were made equal, rather than second, to Augustus' own powers, he was for all intents and purposes a "co-Princeps" with Augustus, and, in the event of the latter's passing, would simply continue to rule without an interregnum or possible upheaval.[33]

However, according to Suetonius, after a two-year stint in Germania, which lasted from 10–12 AD,[34] "Tiberius returned and celebrated the triumph which he had postponed, accompanied also by his generals, for whom he had obtained the triumphal regalia. And before turning to enter the Capitol, he dismounted from his chariot and fell at the knees of his father, who was presiding over the ceremonies.”[35] "Since the consuls caused a law to be passed soon after this that he should govern the provinces jointly with Augustus and hold the census with him, he set out for Illyricum on the conclusion of the lustral ceremonies."[36]

Thus, according to Suetonius, these ceremonies and the declaration of his "co-Princeps" took place in the year 12 AD, after Tiberius' return from Germania.[34] "But he was at once recalled, and finding Augustus in his last illness but still alive, he spent an entire day with him in private."[36] Augustus died in AD 14, a month before his 76th birthday.[37] He was buried with all due ceremony and, as had been arranged beforehand, deified, his will read, and Tiberius, now a middle-aged man at 55, was confirmed as his sole surviving heir.[38]

Emperor (14–37 AD)

Early reign

_preparing_to_perform_a_religious_rite_found_in_the_theater_in_Herculaneum_37_CE_MANN_INV_5615_MH.jpg.webp)

The Senate convened on 18 September, to validate Tiberius's position as Princeps and, as it had done with Augustus before, extend the powers of the position to him.[39] These proceedings are fully accounted by Tacitus.[40] Tiberius already had the administrative and political powers of the Princeps, all he lacked were the titles—Augustus, Pater Patriae, and the Civic Crown (a crown made from laurel and oak, in honor of Augustus having saved the lives of Roman citizens).

Tiberius, however, attempted to play the same role as Augustus: that of the reluctant public servant who wants nothing more than to serve the state.[41][3] This ended up throwing the entire affair into confusion, and rather than humble, he came across as derisive; rather than seeming to want to serve the state, he seemed obstructive.[42] He cited his age as a reason why he could not act as Princeps, stated he did not wish the position, and then proceeded to ask for only a section of the state.[43] Tiberius finally relented and accepted the powers voted to him, though according to Tacitus and Suetonius he refused to bear the titles Pater Patriae, Imperator, and Augustus, and declined the most solid emblem of the Princeps, the Civic Crown and laurels.[44]

This meeting seems to have set the tone for Tiberius's entire rule. He seems to have wished for the Senate and the state to simply act without him and his direct orders were rather vague, inspiring debate more on what he actually meant than on passing his legislation.[45] In his first few years, Tiberius seemed to have wanted the Senate to act on its own,[46] rather than as a servant to his will as it had been under Augustus. According to Tacitus, Tiberius derided the Senate as "men fit to be slaves".[47]

Rise and fall of Germanicus

Problems arose quickly for the new Princeps. The Roman legions posted in Pannonia and Germania had not been paid the bonuses promised them by Augustus, and after a short period of time mutinied when it was clear that a response from Tiberius was not forthcoming.[48] Germanicus and Tiberius's son, Drusus Julius Caesar, were dispatched with a small force to quell the uprising and bring the legions back in line.[49]

Rather than simply quell the mutiny, however, Germanicus rallied the mutineers and led them on a short campaign across the Rhine into Germanic territory, stating that whatever treasure they could grab would count as their bonus.[49] Germanicus's forces crossed the Rhine and quickly occupied all of the territory between the Rhine and the Elbe. Additionally, Tacitus records the capture of the Teutoburg forest and the reclaiming of Roman standards lost years before by Publius Quinctilius Varus,[50] when three Roman legions and their auxiliary cohorts had been ambushed by Germanic tribes.[51]

Germanicus had managed to deal a significant blow to Rome's enemies, quell an uprising of troops, and returned lost standards to Rome, actions that increased the fame and legend of the already very popular Germanicus with the Roman people.[52]

After being recalled from Germania,[53] Germanicus celebrated a triumph in Rome in AD 17,[50] the first full triumph that the city had seen since Augustus' own in 29 BC. As a result, in AD 18 Germanicus was granted control over the eastern part of the empire, just as both Agrippa and Tiberius had received before, and was clearly the successor to Tiberius.[54] Germanicus survived a little over a year before dying, accusing Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the governor of Syria, of poisoning him.[55]

The Pisones had been longtime supporters of the Claudians, and had allied themselves with the young Octavian after his marriage to Livia, the mother of Tiberius. Germanicus's death and accusations indicted the new Princeps. Piso was placed on trial and, according to Tacitus, threatened to implicate Tiberius.[56] Whether the governor actually could connect the Princeps to the death of Germanicus is unknown; rather than continuing to stand trial when it became evident that the Senate was against him, Piso committed suicide.[57][58]

Tiberius seems to have tired of politics at this point. In AD 22, he shared his tribunician authority with his son Drusus,[59] and began making yearly excursions to Campania that reportedly became longer and longer every year. In AD 23, Drusus mysteriously died,[60][61] and Tiberius seems to have made no effort to elevate a replacement. Finally, in AD 26, Tiberius retired from Rome to an Imperial villa-complex he had inherited from Augustus, on the island of Capri. It was just off the coast of Campania, which was a traditional holiday retreat for Rome's upper classes, particularly those who valued cultured leisure (otium) and a Hellenised lifestyle.[62][63]

Tiberius in Capri, with Sejanus in Rome

_2.JPG.webp)

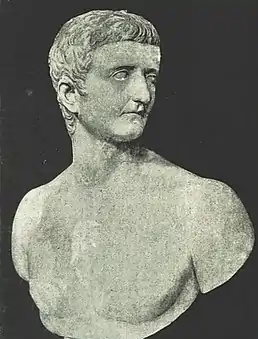

Right: bronze portrait bust of Tiberius in the Cabinet des Médailles, Paris

Lucius Aelius Sejanus had served the imperial family for almost twenty years when he became Praetorian Prefect in AD 15. As Tiberius became more embittered with the position of Princeps, he began to depend more and more upon the limited secretariat left to him by Augustus, and specifically upon Sejanus and the Praetorians. In AD 17 or 18, Tiberius had trimmed the ranks of the Praetorian Guard responsible for the defense of the city, and had moved it from encampments outside of the city walls into the city itself,[64] giving Sejanus access to somewhere between 6000 and 9000 troops.

The death of Drusus elevated Sejanus, at least in Tiberius's eyes, who thereafter refers to him as his 'Socius Laborum' (Partner of my labours). Tiberius had statues of Sejanus erected throughout the city,[65][66] and Sejanus became more and more visible as Tiberius began to withdraw from Rome altogether. Finally, with Tiberius's withdrawal in AD 26, Sejanus was left in charge of the entire state mechanism and the city of Rome.[63]

Sejanus's position was not quite that of successor; he had requested marriage in AD 25 to Tiberius's niece, Livilla,[67] though under pressure quickly withdrew the request.[68] While Sejanus's Praetorians controlled the imperial post, and therefore the information that Tiberius received from Rome and the information Rome received from Tiberius,[69] the presence of Livia seems to have checked his overt power for a time. Her death in AD 29 changed all that.[70]

Sejanus began a series of purge trials of Senators and wealthy equestrians in the city of Rome, removing those capable of opposing his power as well as extending the imperial (and his own) treasury. Germanicus's widow Agrippina the Elder and two of her sons, Nero Julius Caesar and Drusus Caesar were arrested and exiled in AD 30 and later all died in suspicious circumstances. In Sejanus's purge of Agrippina the Elder and her family, Caligula, Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla were the only survivors.[71]

.jpg.webp)

Plot by Sejanus against Tiberius

In 31, Sejanus held the consulship with Tiberius in absentia,[72] and began his play for power in earnest. Precisely what happened is difficult to determine, but Sejanus seems to have covertly attempted to court those families who were tied to the Julians and attempted to ingratiate himself with the Julian family line to place himself, as an adopted Julian, in the position of Princeps, or as a possible regent.[72] Livilla was later implicated in this plot and was revealed to have been Sejanus's lover for several years.[73]

The plot seems to have involved the two of them overthrowing Tiberius, with the support of the Julians, and either assuming the Principate themselves, or serving as regent to the young Tiberius Gemellus or possibly even Caligula.[74] Those who stood in his way were tried for treason and swiftly dealt with.[74]

In AD 31 Sejanus was summoned to a meeting of the Senate, where a letter from Tiberius was read condemning Sejanus and ordering his immediate execution. Sejanus was tried, and he and several of his colleagues were executed within the week.[75] As commander of the Praetorian Guard, he was replaced by Naevius Sutorius Macro.[75]

Tacitus claims that more treason trials followed and that whereas Tiberius had been hesitant to act at the outset of his reign, now, towards the end of his life, he seemed to do so without compunction. The hardest hit were those families with political ties to the Julians. Even the imperial magistracy was hit, as any and all who had associated with Sejanus or could in some way be tied to his schemes were summarily tried and executed, their properties seized by the state. As Tacitus vividly describes,

Executions were now a stimulus to his fury, and he ordered the death of all who were lying in prison under accusation of complicity with Sejanus. There lay, singly or in heaps, the unnumbered dead, of every age and sex, the illustrious with the obscure. Kinsfolk and friends were not allowed to be near them, to weep over them, or even to gaze on them too long. Spies were set round them, who noted the sorrow of each mourner and followed the rotting corpses, till they were dragged to the Tiber, where, floating or driven on the bank, no one dared to burn or to touch them.[76]

However, Tacitus' portrayal of a tyrannical, vengeful emperor has been challenged by some historians: Edward Togo Salmon notes in A history of the Roman world from 30 BC to AD 138:

In the whole twenty two years of Tiberius' reign, not more than fifty-two persons were accused of treason, of whom almost half escaped conviction, while the four innocent people to be condemned fell victims to the excessive zeal of the Senate, not to the Emperor's tyranny.[77]

While Tiberius was in Capri, rumours abounded as to what exactly he was doing there. Suetonius records the rumours of lurid tales of sexual perversity, including graphic depictions of child molestation, and cruelty,[78] and most of all his paranoia.[79] While heavily sensationalized,[80] Suetonius' stories at least paint a picture of how Tiberius was perceived by the Roman senatorial class, and what his impact on the Principate was during his 23 years of rule.

_obverse.jpg.webp)

Final years

The affair of Sejanus and the final years of treason trials permanently damaged Tiberius' image and reputation. After Sejanus's fall, Tiberius' withdrawal from Rome was complete; the empire continued to run under the inertia of the bureaucracy established by Augustus, rather than through the leadership of the Princeps. Suetonius records that he became paranoid,[79] and spent a great deal of time brooding over the death of his son. Meanwhile, during this period a short invasion by Parthia, incursions by tribes from Dacia and from across the Rhine by several Germanic tribes occurred.[81]

Little was done to either secure his succession or indicate how it was to take place; the Julians and their supporters had fallen to the wrath of Sejanus, and his own sons and immediate family were dead. Two of the candidates were either Caligula, the sole surviving son of Germanicus, or Tiberius' own grandson, Tiberius Gemellus.[82] However, Tiberius only made a half-hearted attempt at the end of his life to make Caligula a quaestor, and thus give him some credibility as a possible successor, while Gemellus himself was still only a teenager and thus completely unsuitable for some years to come.[83]

Death (37 AD)

Tiberius died in Misenum on 16 March AD 37, a few months shy of his 78th birthday.[84][85][86] Tacitus relates that the emperor appeared to have stopped breathing, and that Caligula, who was at Tiberius' villa, was being congratulated on his succession to the empire, when news arrived that the emperor had revived and was recovering his faculties. Those who had moments before recognized Caligula as Augustus fled in fear of the emperor's wrath, while Macro took advantage of the chaos to have Tiberius smothered with his own bedclothes.[87] Suetonius reports several rumours, including that the emperor had been poisoned by Caligula, starved, and smothered with a pillow; that recovering, and finding himself deserted by his attendants, he attempted to rise from his couch, but fell dead.[88] According to Cassius Dio, Caligula, fearing that the emperor would recover, refused Tiberius' requests for food, insisting that he needed warmth, not food; then assisted by Macro, he smothered the emperor in his bedclothes.[89]

After his death, the Senate refused to vote Tiberius the divine honors that had been paid to Augustus, and mobs filled the streets yelling "To the Tiber with Tiberius!"; the bodies of criminals were typically thrown into the river, instead of being buried or burnt.[90] However, the emperor was cremated, and his ashes were quietly laid in the Mausoleum of Augustus, later to be scattered in AD 410 during the Sack of Rome.[91]

In his will, Tiberius had left his powers jointly to Caligula and Tiberius Gemellus.[92][93] Caligula's first act on becoming Princeps was to void Tiberius' will.[93]

Legacy

Historiography

Had he died before AD 23, he might have been hailed as an exemplary ruler.[94] Despite the overwhelmingly negative characterization left by Roman historians, Tiberius left the imperial treasury with nearly 3 billion sesterces upon his death.[93][95] Rather than embark on costly campaigns of conquest, he chose to strengthen the existing empire by building additional bases, using diplomacy as well as military threats, and generally refraining from getting drawn into petty squabbles between competing frontier tyrants.[64]

The result was a stronger, more consolidated empire. Of the authors whose texts have survived, only four describe the reign of Tiberius in considerable detail: Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio and Marcus Velleius Paterculus. Fragmentary evidence also remains from Pliny the Elder, Strabo and Seneca the Elder. Tiberius himself wrote an autobiography which Suetonius describes as "brief and sketchy", but this book has been lost.[96]

Publius Cornelius Tacitus

The most detailed account of this period is handed down to us by Tacitus, whose Annals dedicate the first six books entirely to the reign of Tiberius. Tacitus was a Roman senator, born during the reign of Nero in AD 56, and consul suffect in AD 97. His text is largely based on the Acta Senatus (the minutes of the session of the Senate) and the Acta Diurna (a collection of the acts of the government and news of the court and capital), as well as speeches by Tiberius himself, and the histories of contemporaries such as Marcus Cluvius Rufus, Fabius Rusticus and Pliny the Elder (all of which are lost).[94]

Tacitus' narrative emphasizes both political and psychological motivation. His characterisation of Tiberius throughout the first six books is mostly negative, and gradually worsens as his rule declines, identifying a clear breaking point with the death of his son Drusus in AD 23.[94]

Tacitus describes Julio-Claudian rule as generally unjust and "criminal";[97] he attributes the apparent virtues of Tiberius during his early reign to hypocrisy.[84] Another major recurring theme concerns the balance of power between the Senate and the Emperors, corruption, and the growing tyranny among the governing classes of Rome. A substantial amount of his account on Tiberius is therefore devoted to the treason trials and persecutions following the revival of the maiestas law under Augustus.[98] Ultimately, Tacitus' opinion on Tiberius is best illustrated by his conclusion of the sixth book:

His character too had its distinct periods. It was a bright time in his life and reputation, while under Augustus he was a private citizen or held high offices; a time of reserve and crafty assumption of virtue, as long as Germanicus and Drusus were alive. Again, while his mother lived, he was a compound of good and evil; he was infamous for his cruelty, though he veiled his debaucheries, while he loved or feared Sejanus. Finally, he plunged into every wickedness and disgrace, when fear and shame being cast off, he simply indulged his own inclinations.[84]

Suetonius Tranquillus

Suetonius was an equestrian who held administrative posts during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. The Twelve Caesars details a biographical history of the principate from the birth of Julius Caesar to the death of Domitian in AD 96. Like Tacitus, he drew upon the imperial archives, as well as histories by Aufidius Bassus, Marcus Cluvius Rufus, Fabius Rusticus and Augustus' own letters.[78]

His account is more sensationalist and anecdotal than that of his contemporary. The most famous sections of his biography delve into the numerous alleged debaucheries Tiberius remitted himself to while at Capri.[78] Nevertheless, Suetonius also reserves praise for Tiberius' actions during his early reign, emphasizing his modesty.[99]

Velleius Paterculus

One of the few surviving sources contemporary with the rule of Tiberius comes from Velleius Paterculus, who served under Tiberius for eight years (from AD 4) in Germany and Pannonia as praefect of cavalry and legatus. Paterculus' Compendium of Roman History spans a period from the fall of Troy to the death of Livia in AD 29. His text on Tiberius lavishes praise on both the emperor[8][100] and Sejanus.[101] How much of this is due to genuine admiration or prudence remains an open question, but it has been conjectured that he was put to death in AD 31 as a friend of Sejanus.[102]

Gospels, Jews, and Christians

The Gospels mention that during Tiberius' reign, Jesus of Nazareth preached and was executed under the authority of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judaea province. In the Bible, Tiberius is mentioned by name in Luke 3:1,[103] which states that John the Baptist entered on his public ministry in the fifteenth year of his reign. The city of Tiberias (named after Tiberius) referenced in John 6:23 [104] is located on the Sea of Galilee, which was also known as the Sea of Tiberias and is referenced in John 6:1.[105] Many other references to Caesar (or the emperor in some other translations), without further specification, would seem to refer to Tiberius. Similarly, the "tribute penny" referred to in Matthew[106] and Mark[107] is popularly thought to be a silver denarius coin of Tiberius.[108][109][110]

During Tiberius' reign Jews had become more prominent in Rome and Jewish and Gentile followers of Jesus began proselytizing Roman citizens, increasing long-simmering resentments.[111] Tiberius in 19 AD ordered Jews who were of military age to join the Roman Army.[111] Tiberius banished the rest of the Jews from Rome and threatened to enslave them for life if they did not leave the city.[111]

There is considerable debate among historians as to when Christianity was differentiated from Judaism.[111] Most scholars believe that Roman distinction between Jews and Christians took place around AD 70.[111] Tiberius most likely viewed Christians as a Jewish sect rather than a separate, distinct faith.[111] In fact most Romans and Jews, called this new sect (Christianity) "The Way".[112] So it is highly likely that Tiberius referred to Christians as followers of "The Way".

Archaeology

Possible traces remain of personal renovations done by Tiberius in the Gardens of Maecenas, where he lived upon returning from exile in 2 AD.[113] These persist inside the villa's likely triclinium-nymphaeum, the so-called Auditorium of Maecenas.[114] In an otherwise Late Republican-era building, by nature of its brickwork and flooring, the Dionysian-themed landscape and nature frescos lining the walls are reminiscent of the illusionistic early Imperial paintings in his mother's own subterranean dining room.[115]

The palace of Tiberius at Rome was located on the Palatine Hill, the ruins of which can still be seen today. No major public works were undertaken in the city during his reign, except a temple dedicated to Augustus and the restoration of the theater of Pompey,[116][117] both of which were not finished until the reign of Caligula.[118] In addition, remnants of Tiberius' villa at Sperlonga, which includes a grotto where the important Sperlonga sculptures were found in fragments, and the Villa Jovis on top of Capri have been preserved. The estate at Capri is said by Tacitus to have included a total of twelve villas across the island,[63] of which Villa Jovis was the largest.

Tiberius refused to be worshipped as a living god, and allowed only one temple to be built in his honor, at Smyrna.[119] The town Tiberias, in modern Israel on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, was named in Tiberius's honour by Herod Antipas.[120]

The theft of the Gold Tiberius, an unintentionally unique commemorative coin commissioned by Tiberius which is stated to have achieved legendary status in the centuries hence, from a mysterious triad of occultists drives the plot of the framing story in Arthur Machen's 1895 novel The Three Impostors.

Popular culture

Tiberius has been represented in fiction, in literature, film and television, and in video games, often as a peripheral character in the central storyline. One such modern representation is in the novel I, Claudius by Robert Graves,[121] and the consequent BBC television series adaptation, where he is portrayed by George Baker.[122] George R. R. Martin, the author of The Song of Ice and Fire series, has stated that central character Stannis Baratheon is partially inspired by Tiberius Caesar, and particularly the portrayal by Baker.[123]

In the 1968 ITV historical drama The Caesars, Tiberius (by André Morell) is the central character for much of the series and is portrayed in a much more balanced way than in I, Claudius.

He also appears as a minor character in the 2006 film The Inquiry, in which he is played by Max von Sydow. In addition, Tiberius has prominent roles in Ben-Hur (played by George Relph in his last starring role),[124] and in A.D. (played by James Mason).

Played by Ernest Thesiger, he featured in The Robe (1953). He was featured in the 1979 film Caligula, portrayed by Peter O'Toole. He was an important character in Taylor Caldwell's 1958 novel, Dear and Glorious Physician, a biography of St Luke the Evangelist, author of the third canonical Gospel.

He was played by Kenneth Cranham in A.D. The Bible Continues.

In Roman Empire (TV series), Tiberius is portrayed by Craig Walsh-Wrightson.

Children and family

Tiberius was married twice, with only his first union producing a child who would survive to adulthood:

- Vipsania Agrippina, daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (16–11 BC)

- Drusus Julius Caesar (14 BC – 23 AD) (Had Issue)

- Julia the Elder, only daughter of Augustus (11–6 BC)

- Infant son, (dubbed "Tiberillus" by modern historians), died in infancy.

See also

References

- Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories XXVIII.5.23; Capes, p. 71

- "Tiberius". 2006. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- "Tiberius | Roman emperor". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 5

- Levick p. 15

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 6

- Southern, pp. 119–120.

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History II.94

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 9

- Seager, p. xiv.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 8

- Levick, p. 24.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 7

- Strabo, 7. I. 5, p. 292

- Levick, pp. 42.

- Seager 2005, p. 20.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LV.9

- Seager 2005, p. 23.

- Seager 2005, pp. 23–24.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 10

- Levick, p. 29.

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History II.100

- Tacitus, Annals I.53

- Seager 2005, p. 26.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 11

- Seager 2005, p. 28.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 13

- Tacitus, Annals I.3

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 15

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LV.13

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 21. For the debate over whether Agrippa's imperium after 13 BC was maius or aequum, see, e.g., E. Badian (December 1980 – January 1981). "Notes on the Laudatio of Agrippa". Classical Journal. 76 (2): 97–109 [105–106[].

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LV.32

- Seager p. xv

- Speidel, Michael Riding for Caesar: The Roman Emperorors’ Horse guards19

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 20

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 21

- Velleieus Paterculus, Roman History II.123

- Tacitus, Annals I.8

- Levick, pp. 68–81.

- Tacitus, Annals I.9–11

- Seager 2005, pp. 44–45.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 24

- Tacitus, Annals I.12, I.13

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 26

- Tacitus, Annals III.32, III.52

- Tacitus, Annals III.35, III.53, III.54

- Tacitus, Annals III.65

- Tacitus, Annals I.16, I.17, I.31

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.6

- Tacitus, Annals II.41

- Tacitus, Annals II.46

- Shotter, 35–37.

- Tacitus, Annals II.26

- Tacitus, Annals II.43

- Tacitus, Annals II.71

- Tacitus, Annals III.16

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 52

- Tacitus, Annals III.15

- Tacitus, Annals III.56

- Tacitus, Annals, IV.7, IV.8

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 62

- "We must imagine Tiberius not as brooding in isolation (though it is true enough he was a difficult man, not to say a grouchy one), but as entertaining visitors, discussing affairs, and taking up at least the more important of the obligations imposed upon him by state and family": see p. 185ff in Houston, George W., "Tiberius on Capri", Greece and Rome, Volume 32, No. 2 (Oct., 1985), pp. 179–196, Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association, available at JSTOR (subscription required)

- Tacitus, Annals IV.67

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 37

- Tacitus, Annals IV.2

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.21

- Tacitus, Annals IV.39

- Tacitus, Annals IV.40, IV.41

- Tacitus, Annals IV.41

- Tacitus, Annals V.3

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 53, 54

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 65

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.22

- Boddington, Ann (January 1963). "Sejanus. Whose Conspiracy?". The American Journal of Philology. 84 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2307/293155. JSTOR 293155.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LVIII.10

- Tacitus, Annals VI.19

- A history of the Roman world from 30 BC to AD 138, p. 133, Edward Togo Salmon

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 43, 44, 45

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 60, 62, 63, 64

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (1984) Suetonius: The Scholar and His Caesars, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-03000-2

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 41

- Tacitus, Annals VI.46

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.23

- Tacitus, Annals VI.50, VI.51

- Karen Cokayne, Experiencing Old Age In Ancient Rome, p.100

- Flavius Josephus, Steve Mason, Translation and Commentary. Vol. 1B. Judean War 2, p. 153

- Tacitus, Annales, vi. 50.

- Suetonius, "The Life of Tiberius", 73.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, lviii. 28.

- Death of Tiberius: Tacitus Annals 6.50; Dio 58.28.1–4; Suetonius Tiberius 73, Gaius 12.2–3; Josephus AJ 18.225. Posthumous insults: Suetonius Tiberius 75.

- Platner, Samuel Ball; Ashby, Thomas (1929). "Mausoleum Augusti". A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 332–336. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 76

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.1

- Tacitus, Annals IV.6

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 61

- Tacitus, Annals, I.6

- Tacitus, Annals I.72, I.74, II.27–32, III.49–51, III.66–69

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 26–32

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History, II.103–105, II.129–130

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History II.127–128

- Syme, Ronald (1956). "Seianus on the Aventine". Hermes. Franz Steiner Verlag. 84 (3): 257–266. JSTOR 4474933.

- Luke 3:1

- John 6:23

- John 6:1

- Matthew 22:19

- Mark 12:15

- Sir William Smith (1896). The Old Testament History: From The Creation To The Return Of The Jews From Captivity (page 704). Kessinger Publishing, LLC (22 May 2010). ISBN 1-162-09864-3.

- The Numismatist, Volume 29. American Numismatic Association (3 April 2010). 2010. p. 536. ISBN 978-1-148-52633-1.

- Hobson, Burton (1972). Coins and coin collecting (page 28). Dover Publications (April 1972). ISBN 0-486-22763-4.

- Jossa, Giorgio (2006). Jews or Christians. pp. 123–126. ISBN 3-16-149192-0.

- 'Acts 22:4'

- Suetonius, Tiberius 15

- Häuber, Chrystina. "The Horti of Maecenas on the Esquiline Hill in Rome" (PDF). Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Wyler, Stéphanie (2013). "An Augustan Trend towards Dionysos: Around the 'Auditorium of Maecenas'". In Bernabe, Alberto; Herrero deJáuregui, Miguel; San Cristóbal, Ana; Martín Hernández, Raquel (eds.). Redefining Dionysos.

- Tacitus, Annals IV.45, III.72

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 47

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21

- Tacitus, Annals IV.37–38, IV.55–56

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.2.3

- "I, Claudius: From the Autobiography of Tiberius Claudius – Robert Graves". Booktalk.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- "BBC Four Drama – I, Claudius". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- "Not a Blog: It's the Pits". 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2016-12-27.

- "Emperor Tiberius Caesar (Character)". Imdb.com. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History Books 57–58, English translation

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 18, especially ch.6, English translation

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius, Latin text with English translation

- Tacitus, Annals, I–VI, English translation

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History Book II, Latin text with English translation

Secondary material

- Ehrenberg, V.; Jones, A.H.M. (1955). Documents Illustrating the Reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. Oxford.

- Capes, William Wolfe, Roman History, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897

- Levick, Barbara (1999) [1976]. Tiberius the Politician (revised ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21753-9.

- Mason, Ernst (1960). Tiberius. New York: Ballantine Books. (Ernst Mason was a pseudonym of science fiction author Frederik Pohl)

- Seager, Robin (2005) [1972]. Tiberius (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1528-9.

- Shotter, David (2004) [1992]. Tiberius Caesar (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31946-3.

- Salmon, Edward T. (1968) [1944]. A History of the Roman World from 30 B.C. to A.D. 138 (6th ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-10710-9.

- Southern, Pat (1998). Augustus. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16631-4.

- Syme, Ronald (1986). The Augustan Aristocracy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814859-3.

- Syme, Ronald (1974), "History or Biography: the Case of Tiberius", Historia, volume xxiii, pages 481 to 496 and Roman Papers, volume III, pages 936 to 952.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tiberius |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiberius. |

- Fagan, Garrett G. (2001), "Tiberius (A.D. 14–37)", De Imperatoribus Romanis

- "Tiberius (42 BC – 37 AD)" at the BBC

- "Maps of the Roman Empire under Tiberius at Omniatlas.com"

_Pentathlon.svg.png.webp)