Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue

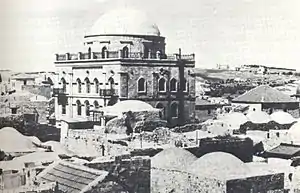

Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (Hebrew: בית הכנסת תפארת ישראל; Ashkenazi Hebrew: Tiferes Yisroel), most often spelled Tiferet Israel, also known as the Nisan Bak Shul, (Yiddish: ניסן ב"ק שול), after its co-founder, Nisan Bak.[1] was a prominent synagogue between 1872 and 1948 in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem.

| Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue | |

|---|---|

בית הכנסת תפארת ישראל | |

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue, before 1948 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Judaism |

| Rite | Nusach Sefard |

| Patron | Rabbi Yisrael Friedman of Ruzhin |

| Location | |

| Location | Jewish Quarter of the Old City |

| Municipality | Jerusalem |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Nisan Bak |

| Destroyed | 21 May 1948 |

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1872 by the Ruzhin Hasidim among the members of the Old Yishuv and was destroyed by the Jordanian Arab Legion on 21 May 1948 during the Battle for Jerusalem of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[2][3]

The synagogue was left as ruins after the recapture of the Old City in the Six-Day War. In November 2012 the Jerusalem municipality announced its approval for plans to rebuild the synagogue.[3] The cornerstone was laid on May 27, 2014.[4]

Origins and name

The synagogue was built in the 1860s by the followers of Rabbi Yisrael Friedman of Ruzhin[2] and his son Rabbi Avrohom Yaakov of Sadigura,[5] and was named "Tiferet Yisrael" after Reb Yisrael[2]—tiferet means "glory" or "splendour" in Hebrew,[6] and Rabbi Yisrael was famous for conducting his court with a regal display of gold and wealth.[7] Nevertheless, the strong involvement of Nissan Bak, led to the widespread use of the name "Nissan Bak synagogue".[8]

Another tradition, published by a relative of the Bak family, holds that it was named after Yisrael Bak (Nissan Bak's father), who had a decisive role in the construction of the synagogue.[8]

Although Hasidim had arrived in Jerusalem by 1747, it was only in 1839 that Nissan Bak began plans for a Hasidic synagogue. Until then they had prayed in small, private locations like Yisrael Bak's house.

In 1843 Nissan Bak traveled from Jerusalem to visit the Ruzhiner Rebbe in Sadigura. He informed him that Czar Nikolai I intended to buy a plot of land near the Western Wall with the intention of building a church and monastery there. The Ruzhiner Rebbe, who was very involved in assisting the yishuv, gave Bak the task to thwart the Czar's attempt. Bak managed to buy the land from its Arab owners for an exorbitant sum mere days before the Czar ordered the Russian counsul in Jerusalem to make the purchase for him. The Czar was forced to buy a different plot of land for a church, which is known today as the Russian Compound.[9] When Rabbi Friedman died in 1851, his son, Rabbi Avrohom Yaakov Friedman, the first Rebbe of Sadigura, continued the task of raising the necessary funds for the project.[10]

Construction

According to Rabbi Menachem Brayer, Nissan Beck (better known as Nisan Bak) was the architect and contractor of the project.[11] Bak consulted architect Martin Ivanovich Eppinger, the very man who was designing the Russian Compound, which had to be built outside the Old City against the initial intentions of the Czar due to the efforts of rabbis Bak and Friedman.[12] A study by architect Faina Milstein concludes that it is likely that Eppinger either fully designed, or at least advised Nisan Bak on the construction of the synagogue.[13]

Initially the Ottoman authorities refused to grant permission to dig the foundations, and when permission was eventually granted, the crew discovered a Muslim sheik's grave on the site. Eventually the Muslim religious judge agreed for the tomb to be moved outside the city walls. After the foundations had been dug, another setback cropped up. It became apparent that it was necessary to obtain a building permit from the officials in Turkey who were not keen to grant the request. Bak, an Austrian national, convinced Franz Joseph I of Austria to intercede, and in 1858 a firman was granted. Over ten years were spent raising funds as the building slowly took shape.[10]

There is a legend, proven by researcher Tamar Hayardeni to be non-factual and to have emerged a good 30 years after the end of the synagogue's construction,[14] that in November 1869 Franz Joseph, en route to the inauguration of the Suez Canal, made a visit to Jerusalem. Included in his itinerary was a tour of the Jewish institutions of the city. When he toured the Old City with Bak and others, he asked why the synagogue was standing without a roof. Bak quipped, "Why, the synagogue took off its hat in honour of Your Majesty!" The Kaiser smiled and replied, "I hope the roof will be built soon", and left the Austrian counsel with 1,000 French francs[15] for the dome's construction. From then on, the dome was referred to by locals as "Franz Joseph's cap".[16]

The three-story synagogue was inaugurated on 19 August 1872, 29 years after the land had been purchased. For the next 75 years, it served as the centre for the Hasidic community in the city. It was considered one of the most beautiful synagogues of Jerusalem, with a commanding view of the Temple Mount, ornate decorations, and beautiful silver objects donated by Hasidim.[17]

- Vintage photographs of synagogue interior

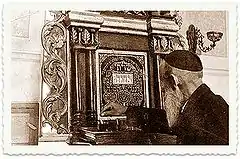

Interior showing raised bimah topped by ornate ironwork, vintage postcard c. 1900.

Interior showing raised bimah topped by ornate ironwork, vintage postcard c. 1900. Interior design showing uppermost section of bimah ironwork, c. 1940.

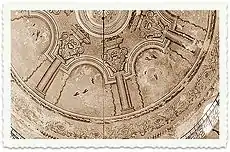

Interior design showing uppermost section of bimah ironwork, c. 1940. Inside of synagogue dome decorated with painted murals, c. 1940.

Inside of synagogue dome decorated with painted murals, c. 1940.

Destruction

During the Israel War of Independence, the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue was used as a post by the Haganah in the defense of the Old City. During the Jordanian Legion's campaign to capture the Old City, it blew up the synagogue an hour after midnight on the night of May 20–21, 1948.

The first major Haganah stronghold to fall was the Nissan Bek Synagogue, the building whose dome had been donated by the Emperor Franz Joseph. It was essential to Rusnack defence plan and the Haganah fought tenaciously to hold on to it…Fawzi el Kutub finally ordered eight of his men to rush across an open space and place a charge at the base of the synagogue. All of them were killed or wounded. No one would volunteer for a second try. Hoping to force his men's hands by his example, Kutub sprinted across the space himself. When he got to the base of the synagogue, he saw that no one had followed him. Like a spider he pressed himself up against its wall until finally the Tunisian to whom he had promised a wife rushed out to him carrying a fifty-five pound charge. The explosion barely chipped the wall. Three more unsuccessful attempts were required before Kutub managed to blow a hole in the synagogue wall and a party of Legionnaires rushed through the smoke into Nissan Bek's interior. Sure that the Haganah would counterattack and that the irregulars swarming into the synagogue would quickly turn to looting, Kutub decided to destroy it with a 220-pound charge. His strongest follower, a one-eyed former porter in the railroad station nicknamed the Whale, staggered up with the explosive. A terrible roar shook the quarter and blew out the heart of the building. As the smoke cleared and the frightful devastation caused by the bomb became apparent, Kutub heard a cry of consternation rising from the Jewish posts around him. It was quickly replaced by a triumphant yell. A small group of Haganah led by Judith Jaharan counterattacked and took the smoking ruins of Nissan Bek from the Arabs. As Kutub had suspected, the irregulars had spent their time looting the synagogue. The Haganah found the bodies of Arab irregulars killed in their counterattack with altar cloths around their waist, pages of the Torah stuffed into their shirts, pieces of chandeliers and lamps in their pockets.[18]

- Destruction of the synagogue, May 1948

The destroyed synagogue, May 1948.

The destroyed synagogue, May 1948. An Arab Legion soldier surveys the synagogue after the demolition of a side wall, May 21, 1948.

An Arab Legion soldier surveys the synagogue after the demolition of a side wall, May 21, 1948. Ruins of the synagogue with bricked-in entrance arches, 1967.

Ruins of the synagogue with bricked-in entrance arches, 1967.

Modern-day ruin and reconstruction plans

Following the Six-Day War, the decision was made to leave the ruins of the synagogue as they were. Only its western wall remains. In 2010, at the dedication of the reconstructed Hurva Synagogue, also destroyed in 1948, plans were announced by the same donors who sponsored the Hurva rebuilding, to rebuild the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue as well.

In November 2012, the Jerusalem municipality approved a plan to rebuild the synagogue. Funding would come from an anonymous donor.[3] In 2014, the synagogue is being rebuilt.

Tiferes Yisroel yeshiva and synagogue

In 1953 Rabbi Mordechai Shlomo Friedman, the Boyaner Rebbe of New York, laid foundations for a new Ruzhiner Torah centre in the New City of Jerusalem to replace the destroyed Ruzhiner synagogue. In 1957 the Ruzhiner yeshiva, called Mesivta Tiferes Yisroel, was inaugurated with the support of all of the Rebbes of the Ruzhiner dynasty.[19] A large synagogue was built adjacent to it, also bearing the name Tiferes Yisroel; the current Boyaner Rebbe, Rabbi Nachum Dov Brayer, leads his Hasidut from here. The design of the synagogue, located on the western end of Malkhei Yisrael Street close to the Central Bus Station, includes a large white dome, reminiscent of the domed Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue that was destroyed in the Old City.

See also

External links

- Early Architectural Drawing of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue – Jerusalem, 1855, an architectural plan with a section and elevation of the proposed building, drawn and signed in Jerusalem in 1855. At 2016 auction page, accessed November 2020.

References

- "Tiferet Israel Synagogue". Jerusalem Municipality. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- Eliyahu Wager (1988). Tiferet Israel Synagogue. Illustrated guide to Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Publishing House. p. 68.

- Melanie Lidman (28 November 2012). "J'lem to rebuild iconic synagogue destroyed in 1948: anonymous donor donates money to rebuild Tifereth Israel, located near Western Wall". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Yossi Aloni (29 May 2014). "Jerusalem Synagogue Destroyed in 1948 to be Rebuilt". Israel Today.

- Assaf, David. "Ruzhin Hasidic Dynasty". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Tehillim 89:17-19, Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB), BibleGateway.com, accessed 30 July 2019

- JNi.Media (10 November 2016). "Report: Trump Connected to Hasidic Court Whose Founder Lived in Gold Palace". The Jewish Express. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Leon Majaro; Simon Majaro (translation from Hebrew; editor; copyright) (2009). The House of Rokach. Majaro Publications. p. 14, footnote. ISBN 978-0-9562859-0-4. Retrieved 30 July 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brayer, Rabbi Menachem (2003). The House of Rizhin: Chassidus and the Rizhiner dynasty. Mesorah Publications. pp. 260–261. ISBN 1-57819-794-5.

- Rossoff, Dovid (1999). Where Heaven Touches Earth. Jerusalem, Israel: Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 0-87306-879-3.

- Brayer, The House of Rizhin, p. 261.

- Zohar, Gil (25 January 2019). "Tiferet Yisrael to be rebuilt". Jewish Independent. Vancouver. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- Milstein, Faina (2005–2006). Gafni, Reuven; Ben-Gedalia, Yochai; Gelman, Uriel (eds.). בית הכנסת "תפארת ישראל": עיון אדריכלי ואורבני [lit.: Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue: Urban and architectural study]. גבוה מעל גבוה (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi. pp. 209–230.

- Tamar Hayardeni (16 September 2013). "The Kaiser's Cap". Segula Magazine. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Horovitz, Ahron (2000). Jerusalem, Footsteps Through Time. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers. pp. 192–194. ISBN 1-58330-398-7.

- Brayer, The House of Rizhin, p. 262.

- Brayer, The House of Rizhin, p. 263.

- Collins, Larry; Dominique Lapierre (1973). "Ticket to a Promised Land". O Jerusalem!. London: Pan Books. pp. 465–466. ISBN 0-330-23514-1. LCCN 97224015.

- Brayer, The House of Ruzhin, p. 459.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (Jerusalem). |