Old City (Jerusalem)

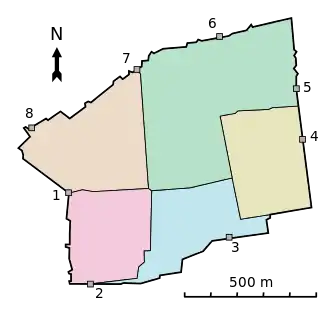

The Old City (Hebrew: הָעִיר הָעַתִּיקָה, Ha'Ir Ha'Atiqah, Arabic: البلدة القديمة, al-Balda al-Qadimah) is a 0.9-square-kilometer (0.35 sq mi) walled area[2] within the modern city of Jerusalem.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 148 |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th session) |

| Endangered | 1982–present |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

-Aerial-Temple_Mount-(south_exposure).jpg.webp) |

| Sieges |

| Places |

| Political status |

| Other topics |

The history of the Old City has been documented in significant detail, notably in old maps of Jerusalem over the last 1,500 years. This area constituted the entire city of Jerusalem until the late 19th century; neighbouring villages such as Silwan, and new Jewish neighborhood such Mishkenot Sha'ananim, later became part of the municipal boundaries.

The Old City is home to several sites of key religious importance: the Temple Mount and Western Wall for Jews, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque for Muslims. It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site List in 1981.

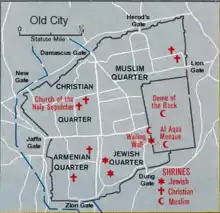

Traditionally, the Old City has been divided into four uneven quarters, although the current designations were introduced only in the 19th century.[3] Today, the Old City is roughly divided (going counterclockwise from the northeastern corner) into the Muslim, Christian, Armenian and Jewish Quarters. The Old City's monumental defensive walls and city gates were built in 1535–1542 by the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[4]

Population

The current population of the Old City resides mostly in the Muslim and Christian quarters. As of 2007 the total population was 36,965; the breakdown of religious groups in 2006 was 27,500 Muslims (up from ca. 17,000 in 1967, with over 30,000 by 2013, tendency: growing); 5,681 Christians (ca. 6,000 in 1967), not including the 790 Armenians (down to ca. 500 by 2011, tendency: decreasing); and 3,089 Jews (starting with none in 1967, as they were evicted after the Old City was captured by Jordan following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, with almost 3,000 plus some 1,500 yeshiva students by 2013, tendency: growing).[5][6][7]

Political status

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Old City was captured by Jordan and all its Jewish residents were evicted. During the Six-Day War in 1967, which saw hand-to-hand fighting on the Temple Mount, Israeli forces captured the Old City along with the rest of East Jerusalem, subsequently annexing them as Israeli territory and reuniting them with the western part of the city. Today, the Israeli government controls the entire area, which it considers part of its national capital. However, the Jerusalem Law of 1980, which effectively annexed East Jerusalem to Israel, was declared null and void by United Nations Security Council Resolution 478. East Jerusalem is now regarded by the international community as part of occupied Palestinian territory.[8][9]

History

Biblical Jebus, Kings David and Solomon

According to the Hebrew Bible, before King David's conquest of Jerusalem in the 11th century BCE the city was home to the Jebusites. The Bible describes the city as heavily fortified with a strong city wall, a fact confirmed by archaeology. The Bible names the city ruled by King David as the City of David, in Hebrew Ir David, which was identified southeast of the Old City walls, outside the Dung Gate. In the Bible, David's son, King Solomon, extended the city walls to include the Temple and Temple Mount.

Assyrian period to 70 CE destruction

The city was largely extended westwards after the Neo-Assyrian destruction of the northern Kingdom of Israel and the resulting influx of refugees. Destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BCE, it was rebuilt on a smaller scale in about 440 BCE, during the Persian period, when, according to the Bible, Nehemiah led the Jews who returned from the Babylonian Exile. An additional, so-called Second Wall, was built by King Herod the Great. In 41–44 CE, Agrippa, king of Judea, started building the so-called "Third Wall" around the northern suburbs. The entire city was totally destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE.

Late Roman, Byzantine, and Early Muslim periods

The northern part of the city was rebuilt by the Emperor Hadrian around 130, under the name Aelia Capitolina. In the Byzantine period Jerusalem was extended southwards and again enclosed by city walls.

Muslims occupied Byzantine Jerusalem in the 7th century (637 CE) under the second caliph, `Umar Ibn al-Khattab who annexed it to the Islamic Arab Empire. He granted its inhabitants an assurance treaty. After the siege of Jerusalem, Sophronius welcomed `Umar, allegedly because, according to biblical prophecies known to the Church in Jerusalem, "a poor, but just and powerful man" would rise to be a protector and ally to the Christians of Jerusalem. Sophronius believed that `Umar, a great warrior who led an austere life, was a fulfillment of this prophecy. In the account by the Patriarch of Alexandria, Eutychius, it is said that `Umar paid a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and sat in its courtyard. When the time for prayer arrived, however, he left the church and prayed outside the compound, in order to avoid having future generations of Muslims use his prayer there as a pretext for converting the church into a mosque. Eutychius adds that `Umar also wrote a decree which he handed to the Patriarch, in which he prohibited Muslims gathering in prayer at the site.[10]

Crusader & Ayyubid periods

In 1099, Jerusalem was captured by the Western Christian army of the First Crusade and it remained in their hands until recaptured by the Arab Muslims, led by Saladin, on October 2, 1187. He summoned the Jews and permitted them to resettle in the city. In 1219, the walls of the city were razed by Sultan Al-Mu'azzam of Damascus; in 1229, by treaty with Egypt, Jerusalem came into the hands of Frederick II of Germany. In 1239 he began to rebuild the walls, but they were demolished again by Da'ud, the emir of Kerak. In 1243, Jerusalem came again under the control of the Christians, and the walls were repaired. The Kharezmian Tatars took the city in 1244 and Sultan Malik al-Muazzam razed the walls, rendering it again defenseless and dealing a heavy blow to the city's status.

Ottoman period

The current walls of the Old City were built in 1535–42 by the Ottoman Turkish sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The walls stretch for approximately 4.5 km (2.8 miles), and rise to a height of between 5 and 15 metres (16.4–49 ft), with a thickness of 3 metres (10 feet) at the base of the wall.[4] Altogether, the Old City walls contain 35 towers, of which 15 are concentrated in the more exposed northern wall.[4] Suleiman's wall had six gates, to which a seventh, the New Gate, was added in 1887; several other, older gates, have been walled up over the centuries. The Golden Gate was at first rebuilt and left open by Suleiman's architects, only to be walled up a short while later. The New Gate was opened in the wall surrounding the Christian Quarter during the 19th century. Two secondary gates were reopened in recent times on the southeastern side of the city walls as a result of archaeological work.

UNESCO status

In 1980, Jordan proposed that the Old City be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[11] It was added to the List in 1981.[12] In 1982, Jordan requested that it be added to the List of World Heritage in Danger. The United States government opposed the request, noting that the Jordanian government had no standing to make such a nomination and that the consent of the Israeli government would be required since it effectively controlled Jerusalem.[13] In 2011, UNESCO issued a statement reiterating its view that East Jerusalem is "part of the occupied Palestinian territory, and that the status of Jerusalem must be resolved in permanent status negotiations."[14]

Archaeology

Hellenistic period

In 2015, archaeologists uncovered the remnants of an impressive fort, built by Greeks in the center of old Jerusalem. It is believed that it is the remnants of the Acra fortress. The team also found coins that date from the time of Antiochus IV to the time of Antiochus VII. In addition, they found Greek arrowheads, slingshots, ballistic stones and amphorae.[15]

In 2018, archaeologists discovered a 4 centimeter long filigree gold earring with a ram's head, around 200 meters south of the Temple Mount. The Israel Antiquities Authority said it was consistent with jewelry from the early Hellenistic period (3rd or early 2nd century BCE). Adding that it was the first time somebody finds a golden earring from the Hellenistic times in Jerusalem.[16]

Byzantine period

In the 1970s, while excavating the remains of the Nea Church (the New Church of the Theotokos), a Greek inscription was found. It reads: "This work too was donated by our most pious Emperor Flavius Justinian, through the provision and care of Constantine, most saintly priest and abbot, in the 13th year of the indiction."[17][18] A second dedicatory inscription bearing the names of Emperor Justinian and of the same abbot of the Nea Church was discovered in 2017 among the ruins of a pilgrim hostel about a kilometre north of Damascus Gate, which proves the importance of the Nea complex at the time.[18][19]

Quarters

The Old City is divided into four quarters: the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Armenian Quarter and the Jewish Quarter. Despite the names, there was no governing principle of ethnic segregation: 30 percent of the houses in the Muslim quarter were rented out to Jews, and 70 percent of the Armenian quarter.[20]

Muslim Quarter

The Muslim Quarter (Arabic: حارَة المُسلِمين, Hārat al-Muslimīn) is the largest and most populous of the four quarters and is situated in the northeastern corner of the Old City, extending from the Lions' Gate in the east, along the northern wall of the Temple Mount in the south, to the Western Wall – Damascus Gate route in the west. During the British Mandate, Sir Ronald Storrs embarked on a project to rehabilitate the Cotton Market, which was badly neglected under the Turks. He describes it as a public latrine with piles of debris up to five feet high. With the help of the Pro-Jerusalem Society, vaults, roofing and walls were restored, and looms were brought in to provide employment.[21]

Like the other three quarters of the Old City, until the riots of 1929 the Muslim quarter had a mixed population of Muslims, Christians, and also Jews.[22] Today, there are "many Israeli settler homes" and "several yeshivas", including Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim, in the Muslim Quarter.[5] Its population was 22,000 in 2005.

Christian Quarter

The Christian Quarter (Arabic: حارة النصارى, Ḩārat an-Naşāra) is situated in the northwestern corner of the Old City, extending from the New Gate in the north, along the western wall of the Old City as far as the Jaffa Gate, along the Jaffa Gate – Western Wall route in the south, bordering the Jewish and Armenian Quarters, as far as the Damascus Gate in the east, where it borders the Muslim Quarter. The quarter contains the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, viewed by many as Christianity's holiest place.

Armenian Quarter

The Armenian Quarter (Armenian: Հայկական Թաղամաս, Haygagan T'aġamas, Arabic: حارة الأرمن, Ḩārat al-Arman) is the smallest of the four quarters of the Old City. Although the Armenians are Christian, the Armenian Quarter is distinct from the Christian Quarter. Despite the small size and population of this quarter, the Armenians and their Patriarchate remain staunchly independent and form a vigorous presence in the Old City. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the four quarters of the city came under Jordanian control. Jordanian law required Armenians and other Christians to "give equal time to the Bible and Qur'an" in private Christian schools, and restricted the expansion of church assets. The 1967 war is remembered by residents of the quarter as a miracle, after two unexploded bombs were found inside the Armenian monastery. Today, more than 3,000 Armenians live in Jerusalem, 500 of them in the Armenian Quarter.[23][24] Some are temporary residents studying at the seminary or working as church functionaries. The Patriarchate owns the land in this quarter as well as valuable property in West Jerusalem and elsewhere. In 1975, a theological seminary was established in the Armenian Quarter. After the 1967 war, the Israeli government gave compensation for repairing any churches or holy sites damaged in the fighting, regardless of who caused the damage.

Jewish Quarter

.jpg.webp)

The Jewish Quarter (Hebrew: הרובע היהודי, HaRova HaYehudi, known colloquially to residents as HaRova, Arabic: حارة اليهود, Ḩārat al-Yahūd) lies in the southeastern sector of the walled city, and stretches from the Zion Gate in the south, bordering the Armenian Quarter on the west, along the Cardo to Chain Street in the north and extends east to the Western Wall and the Temple Mount. The quarter has a rich history, with several long periods of Jewish presence covering much of the time since the eighth century BCE.[25][26][27][28][29] In 1948, its population of about 2,000 Jews was besieged, and forced to leave en masse.[30] The quarter was completely sacked by Arab forces during the Battle for Jerusalem and ancient synagogues were destroyed.

The Jewish quarter remained under Jordanian control until its recapture by Israeli paratroopers in the Six-Day War of 1967. A few days later, Israeli authorities ordered the demolition of the adjacent Moroccan Quarter, forcibly relocating all of its inhabitants, in order to facilitate public access to the Western Wall. 195 properties -synagogues, yeshivas, and apartments - wer registered as Jewish and fell under the control of Jordan's Custodian of Enemy Property. Most were occupied by Palestinian refugees expelled by Israeli forces from West Jerusalem and its contiguous villages until UNWRA and Jordan constructed the Shuafat Refugee Camp, where many were shifted, leaving most of the properties empty of inhabitants.[31]

In 1968, after the Six Day War, Israel confiscated 12%, including the Jewish quarter and contiguous areas, of the Old City for public use. Some 80% of this confiscated infrastructure consisted of properties not owned by Jews.[31] After reconstruction the parts of the quarter destroyed prior to 1967, these properties were then offered for sale exclusively to the Israeli and Jewish public. The prior owners mostly refused because their properties were part of Islamic of family waqfs, which cannot be put up for sale.[31] As of 2005, the population stands at 2,348. (as of 2005).[32] Many large educational institutions have taken up residence. Before being rebuilt, the quarter was carefully excavated under the supervision of Hebrew University archaeologist Nahman Avigad. The archaeological remains are on display in a series of museums and outdoor parks, which tourists can visit by descending two or three stories beneath the level of the current city. The former Chief Rabbi is Avigdor Nebenzahl, and the current Chief Rabbi is his son Chizkiyahu Nebenzahl, who is on the faculty of Yeshivat Netiv Aryeh, a school situated directly across from the Western Wall.

The quarter includes the "Karaites' street" (Hebrew: רחוב הקראים, Rhehov Ha'karaim), on which the old Anan ben David Kenesa is located.[33]

Moroccan Quarter

There was previously a small Moroccan quarter in the Old City. Within a week of the Six-Day War's end, the Moroccan quarter was largely destroyed in order to give visitors better access to the Western Wall by creating the Western Wall plaza. The parts of the Moroccan Quarter that were not destroyed are now part of the Jewish Quarter. Simultaneously with the demolition, a new regulation was set into place by which the only access point for non-Muslims to the Temple Mount is through the Gate of the Moors, which is reached via the so-called Mughrabi Bridge.[34][35]

Gates

During different periods, the city walls followed different outlines and had a varying number of gates. During the era of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem for instance, Jerusalem had four gates, one on each side. The current walls were built by Suleiman the Magnificent, who provided them with six gates; several older gates, which had been walled up before the arrival of the Ottomans, were left as they were. As to the previously sealed Golden Gate, Suleiman at first opened and rebuilt it, but then walled it up again as well. The number of operational gates increased to seven after the addition of the New Gate in 1887; a smaller eighth one, the Tanners' Gate, has been opened for visitors after being discovered and unsealed during excavations in the 1990s. The sealed historic gates comprise four that are at least partially preserved (the double Golden Gate in the eastern wall, and the Single, Triple, and Double Gates in the southern wall), with several other gates discovered by archaeologists of which only traces remain (the Gate of the Essenes on Mount Zion, the gate of Herod's royal palace south of the citadel, and the vague remains of what 19th-century explorers identified as the Gate of the Funerals (Bab al-Jana'iz) or of al-Buraq (Bab al-Buraq) south of the Golden Gate[36]).

Until 1887, each gate was closed before sunset and opened at sunrise. As indicated by the chart below, these gates have been known by a variety of names used in different historical periods and by different communities.

See also

References

- "Old City of Jerusalem and its Walls". UNESCO. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Kollek, Teddy (1977). "Afterword". In John Phillips (ed.). A Will to Survive – Israel: the Faces of the Terror 1948-the Faces of Hope Today. Dial Press/James Wade.

about 225 acres

- Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua (1984). Jerusalem in the 19th Century, The Old City. Yad Izhak Ben Zvi & St. Martin's Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-312-44187-8.

- Eliyahu Wager (1988). Illustrated guide to Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Publishing House. p. 138.

- "Jerusalem The Old City: Urban Fabric and Geopolitical Implications" (PDF). International Peace and Cooperation Center. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-28.

- Bracha Slae (13 July 2013). "Demography in Jerusalem's Old City". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Beltran, Gray (9 May 2011). "Torn between two worlds and an uncertain future". Columbia Journalism School. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns Archived 2013-07-21 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory. December 2012

- Benveniśtî, Eyāl (2004). The international law of occupation. Princeton University Press. pp. 112–13. ISBN 978-0-691-12130-7.

- "The Holy Sepulchre – first destructions and reconstructions". Christusrex.org. 2001-12-26. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- Advisory Body Evaluation (PDF file)

- "Report of the 1st Extraordinary Session of the World Heritage Committee". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- "Justification for inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger, 1982: Report of the 6th Session of the World Heritage Committee". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- "UNESCO replies to allegations". UNESCO. 15 July 2011.

The Old City of Jerusalem is inscribed on the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger. UNESCO continues to work to ensure respect for the outstanding universal value of the cultural heritage of the Old City of Jerusalem. This position is reflected on UNESCO’s official website (www.unesco.org). In line with relevant UN resolutions, East Jerusalem remains part of the occupied Palestinian territory, and the status of Jerusalem must be resolved in permanent status negotiations.

- Jerusalem Dig Uncovers Ancient Greek Citadel

- In find of ancient gold earring, echoes of Greek rule over Jerusalem

- Greek building inscription with a cross

- Outside Jerusalem’s Old City, a once-in-a-lifetime find of ancient Greek inscription

- Important ancient inscription unearthed near the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem

- Menachem Klein, 'Arab Jew in Palestine,' Israel Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Fall 2014), pp. 134-153 p.139

- Discerning Conqueror, Haaretz

- "שבתי זכריה עו"ד חצרו של ר' משה רכטמן ברחוב מעלה חלדיה בירושלים העתיקה". Jerusalem-stories.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- Հայաստան սփյուռք [Armenia Diaspora] (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

- Առաքելական Աթոռ Սրբոց Յակովբեանց Յերուսաղեմ [Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem (literally "Apostolic See of St. James in Jerusalem")] (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-09.

- University of Cape Town, Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Congress, South African Judaica Society 81(1986) (referencing archaeological evidence of "Israelite settlement of the Western Hill from the 8th Century BCE onwards").

- Simon Goldhill, Jerusalem: City of Longing 4 (2008) (conquered by "early Israelites" after the "ninth century B.C.")

- William G. Dever & Seymour Gitin (eds.), Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age Through Roman Palaestina 534 (2003) ("in the 8th–7th centuries B.C.E. ... Jerusalem was the capital of the Judean kingdom . ... It encompassed the entire City of David, the Temple Mount, and the Western Hill, now the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.")

- Hillel Geva (ed.), 1 Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1969–1982 81 (2000) ("The settlement in the Jewish Quarter began during the 8th century BCE. ... the Broad Wall was apparently erected by King Hezekiah of Judah at the end of the 8th century BCE.")

- Koert van Bekkum, From Conquest to Coexistence: Ideology and Antiquarian Intent in the Historiography of Israel’s Settlement in Canaan 513 (2011) ("During the last decennia, a general consensus was reached concerning Jerusalem at the end of Iron IIB. The extensive excavations conducted ... in the Jewish Quarter ... revealed domestic constructions, industrial installations and large fortifications, all from the second half of the 8th century BCE.")

- Mordechai Weingarten

- Dumper, Michael (2017). Najem, Tom; Molloy, Michael J.; Bell, Michael; Bell, John (eds.). Contested Sites in Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Old City Initiative. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-317-21344-4.

- Staff. "Table III/14 – Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter, and Statistical Area, 2003" (PDF). Institute for Israel Studies (in Hebrew and English). Institute for Israel Studies, Jerusalem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Staff (2010). "Our communities". God's name to succeed (in Hebrew). World Karaite Judaism. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Nadav Shragai (8 March 2007). "The Gate of the Jews". Haaretz. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Steinberg, Gerald M. (2013). "False Witness? EU Funded NGOs and Policymaking in the Arab-Israeli Conflict" (PDF). Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs.

- Gülru Necipoğlu (2008). "The Dome of the Rock as a palimpsest: 'Abd al-Malik's grand narrative and Sultan Süleyman's glosses" (PDF). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic. Leiden: Brill. 25: 20–21. ISBN 9789004173279. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old City (Jerusalem). |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jerusalem/Old City. |