Tikal Temple IV

Tikal Temple IV is a Mesoamerican pyramid in the ruins of the ancient Maya city of Tikal in modern Guatemala. It was one of the tallest and most voluminous buildings in the Maya world.[1] The pyramid was built around 741 AD.[1] Temple IV is located at the western edge of the site core.[1] Two causeways meet at the temple; the Tozzer Causeway runs east to the Great Plaza, while the Maudslay Causeway runs northeast to the Northern Zone.[1] Temple IV is the second tallest pre-Columbian structure still standing in the New World, just after the Great Pyramid of Toniná in Chiapas, Mexico,[2] although Teotihuacan's Pyramid of the Sun may once have been taller.[3]

The pyramid was built to mark the reign of the 27th king of the Tikal dynasty, Yik'in Chan K'awiil, although it may have been built after his death as his funerary temple.[4] Archaeologists believe that Yik'in Chan K'awiil's tomb lies undiscovered somewhere underneath the temple.[5] The summit shrine faces eastward to the site core, with Temple III visible directly in front and Temple I and Temple II beyond it.[3]

The structure

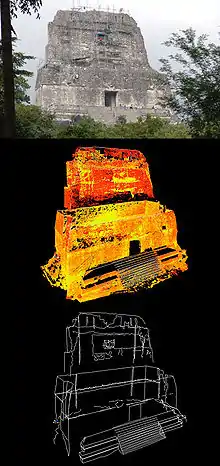

The pyramid has a rectangular base with its long axis running north–south.[1] It stands 64.6 metres (212 ft) from its supporting platform to the highest part of the roof comb.[3] Archaeologists estimate that 190,000 cubic metres (6,700,000 cu ft) of construction material were utilised in the bulk of the pyramid.[3] The temple faces eastwards towards the site core and supports a massive roof comb in pure Petén style, which was built upon the highest part of the structure's rear. It was hollow and was faced with an enormous mosaic sculpture.[1] The architecture of Temple IV is broadly similar to that of the other major temples at Tikal, such as Temple I and Temple II.[3]

The pyramid body itself, excluding the superstructure, consists of seven stepped levels with slanting talud walls and multiple corners. The lowest of these levels measures 88 by 65 metres (289 by 213 ft), whilst the uppermost platform measures 38.5 by 19.6 metres (126 by 64 ft). The pyramid was built on top of an enormous supporting platform that measures 144 by 108 metres (472 by 354 ft); this platform had two levels and rounded corners; it was accessed via a 44-metre (144 ft) wide projecting stairway. The supporting platform was of very high-quality and utilised enormous stones in its construction.[6]

The summit shrine was accessed via a 16.3-metre (53 ft) wide stairway that climbed from the supporting platform; a plain stela (Stela 43) and the associated Altar 35 are centrally located at the base of the stairway.[7] The shrine has been partially restored and has walls up to 12 metres (39 ft) thick. The shrine was built upon a platform resting upon a supplementary platform, which was in turn seated upon the top of the pyramid.[3]

The supplementary platform measures 33 by 20 metres (108 by 66 ft) with the longer axis running north–south. A stairway projects eastwards from this, giving access to the shrine itself. The supplementary platform is not exactly rectangular but consists of a number of architectural elements forming a complex plan. The platform resting on top of this measures 0.9 metres (3.0 ft) high; this element is poorly preserved, being visible only on the east side and in the middle of the north and south sides.[1]

The roof comb is 12.86 metres (42.2 ft) high and consists of three distinct levels. The massive bulk of the roof comb was lightened by internal chambers, with four being built into each of the three levels. The roof comb was originally somewhat taller as evidenced by the bases of three smaller architectural elements on top.[1]

The shrine

The shrine measures 31.9 by 12.1 metres (105 by 40 ft), with a maximum height of 8.9 metres (29 ft) excluding the roof comb.[6] The exterior walls of the shrine are vertical, contrasting with the rest of the pyramid.[6] The upper sections of the exterior walls formed a frieze, with three giant stone mosaic masks facing eastwards over the temple access.[6] The central mask was directly over the outer doorway, while the other two were near the northern and southern extremes of the building's facade.[6]

The shrine had three chambers situated one behind the other, each linked by a doorway with a lintel fashioned from sapodilla wood.[8] These three rooms were the only accessible chambers in the entire pyramid temple.[6] The lintel of the exterior doorway was plain but the two interior lintels were intricately carved.[3] These two were removed in 1877 by Gustav Bernoulli and are now found in the Ethnographic Museum in Basel in Switzerland.[9] The lintels were carved elsewhere and then moved to the pyramid, raised to the summit shrine and installed in prepared positions; this was a laborious task given that sapodilla wood weighs 1120 kg/m3 (69.1 lb/cubic foot).[8] It was only after the installation of the lintels that the shrine was roofed and the roof comb built.[10]

The hieroglyphic inscriptions on the sculpted lintels indicate that the temple was built in 741 AD, and radiocarbon dating of the lintels and wooden beams in the vaulting confirmed this, giving a result of 720±60 AD.[10]

Lintel 3 is a wooden panel measuring 1.76 by 2.05 metres (5.8 by 6.7 ft) that is carved in low relief.[11] It depicts the Tikal king Yik'in Chan K'awiil seated on a litter underneath the arch of a celestial serpent. The lintel was sculpted to mark his victory over the city of El Perú in 743.[12] It has two panels of hieroglyphic script, containing a total of 64 glyphs.[11]

Modern history

The Tikal Project of the University of Pennsylvania stabilised the ruins of the pyramid between 1964 and 1969, carrying out some limited restoration work to the upper part of the temple.[1] The National Tikal Project (Proyecto Nacional Tikal) carried out emergency repairs in the second half of the 1970s.[1]

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

Gallery

Interior of shrine

Interior of shrine Summit

Summit Corner detail

Corner detail 2010 restoration work

2010 restoration work

See also

Notes

- Morales et al 2008, p.421.

- https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/29-zona-arqueologica-de-tonina

- Coe 1967, 1988, p.80.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp.304, 403.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.417.

- Morales et al 2008, p.422.

- Coe 1967, 1988, p.80. Morales et al 2008, p.422.

- Coe 1967, 1988, pp.80-81.

- Coe 1967, 1988, p.80. Pérez de Lara.

- Coe 1967, 1988, p.81.

- Rubio 1992, p.189.

- Martin and Grube 2000, p.49.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tikal Temple IV. |

- Coe, William R. (1988) [1967]. Tikal: Guía de las Antiguas Ruinas Mayas (in Spanish). Guatemala: Piedra Santa. ISBN 84-8377-246-9.

- Martin, Simon; Nikolai Grube (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.

- Morales, Tirso; Benito Burgos; Miguel Acosta; Sergio Pinelo; Marco Tulio Castellanos; Leopoldo González; Francisco Castañeda; Edy Barrios; Rudy Larios; et al. (2008). "Trabajos realizados por la Unidad de Arqueología del Parque Nacional Tikal, 2006-2007" (PDF). XXI Simposio de Arqueología en Guatemala, 2007 (edited by J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo and H. Mejía) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 413–436. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- Pérez de Lara, Jorge. "A Brief History of the Rediscovery of Tikal and Archaeological Work at the Site". Mesoweb. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Rubio, Rolando R. (1992). "Análisis iconografico y epigrafico del Dintel 3 del Templo IV de Tikal, Guatemala" (PDF). IV Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1990 (edited by J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo and S. Brady) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 189–198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

Further reading

- Ponciano, Erick; Jari López; Nicte Mazariegos; José Maria Anavisca (2012). B. Arroyo; L. Paiz; H. Mejía (eds.). "Arquitectura monumental en la dedicación de templos dinasticos, Templo IV, Tikal, Petén" (PDF). Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, Instituto de Antropología e Historia and Asociación Tikal. XXV (2011): 905–909. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

.png.webp)