Tim Hardin

James Timothy Hardin (December 23, 1941 – December 29, 1980)[1] was an American folk musician and composer. He wrote the Top 40 hit "If I Were a Carpenter", covered by, among others, Bobby Darin, Bob Dylan, Bob Seger, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, The Four Tops, Robert Plant, Small Faces, Johnny Rivers, and Bert Jansch; his song "Reason to Believe" has also been covered by many artists, notably Rod Stewart (who had a chart hit with the song), Neil Young, and The Carpenters. The Nice also recorded and performed live a popular version of Hardin's song "Hang On To A Dream" based on a piano arrangement by Keith Emerson. Hardin is also known for his own recording career.

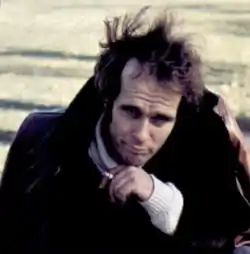

Tim Hardin | |

|---|---|

Tim Hardin in 1969 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Timothy Hardin |

| Also known as | Tim Hardin |

| Born | December 23, 1941 Eugene, Oregon, US |

| Died | December 29, 1980 (aged 39) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Genres | Folk |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter |

| Instruments | Vocals, guitar, piano |

| Years active | 1964–1980 |

| Labels | Verve, Columbia |

Early life and career

Hardin was born in Eugene, Oregon, and attended South Eugene High School. He dropped out of high school at age 18 to join the Marine Corps. Hardin is said to have discovered heroin while posted in Southeast Asia.[2]

After his discharge he moved to New York City in 1961, where he briefly attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.[2] He was excluded owing to truancy and began to focus on his musical career by performing around Greenwich Village, mostly in a blues style.[3]

After moving to Boston in 1963 he was discovered by the record producer Erik Jacobsen (later the producer for The Lovin' Spoonful), who arranged a meeting with Columbia Records.[4] In 1964 he moved back to Greenwich Village to record for his contract with Columbia. The resulting recordings were not released and Columbia terminated Hardin's recording contract.[5]

After moving to Los Angeles in 1965, he met actress Susan Yardley Morss (known professionally as Susan Yardley),[2][6] and moved back to New York with her. He signed to the Verve Forecast label, and produced his first authorized album, Tim Hardin 1 in 1966 which contained "Reason To Believe" and the ballad "Misty Roses", which received Top 40 radio play.

Tim Hardin 2 was released in 1967; it contained "If I Were a Carpenter". A British tour was cut short after Hardin contracted pleurisy.[7]

An album entitled This is Tim Hardin, featuring covers of "House of the Rising Sun", Fred Neil's "Blues on the Ceiling" and Willie Dixon's "Hoochie Coochie Man", among others, appeared in 1967, on the Atco label. The liner notes indicate that the songs were recorded in 1963–1964, well prior to the release of Tim Hardin 1. In 1968, Verve released Tim Hardin 3 Live in Concert, a collection of live recordings along with re-makes of previous songs. It was followed by Tim Hardin 4, another collection of blues-influenced tracks believed to date from the same period as This is Tim Hardin. In September 1968 he and Van Morrison shared a bill at the Cafe au Go Go, at which each performed an acoustic set.[8]

In 1969, Hardin again signed with Columbia and had one of his few commercial successes, as a non-LP single of Bobby Darin's "Simple Song of Freedom" reached the US Top 50. Hardin did not tour in support of this single—his heroin use and stage fright made his live performances erratic.[2]

Also in 1969 he appeared at the Woodstock Festival, where he sang "If I Were a Carpenter" solo and played a set of his music while backed by a full band. None of his performances were included in the documentary film or the original soundtrack album.[2] His performance of "If I Were a Carpenter" was included on the 1994 box-set Woodstock: Three Days of Peace and Music.

He recorded three albums for Columbia—Suite for Susan Moore and Damion: We Are One, One, All in One; Bird on a Wire; and Painted Head.

Later work and death

During the following years Hardin moved between Britain and the U.S. His heroin addiction had taken control of his life by the time his last album, Nine, was released on GM Records in the UK in 1973 (the album did not see a U.S. release until it appeared on Antilles Records in 1976). He sold the writers' rights to his songs, but accounts of how this transpired differ.[2]

In late November 1975 Hardin performed as guest lead vocalist with the German experimental rock band Can, for two UK concerts at Hatfield Polytechnic in Hertfordshire and London's Drury Lane Theatre. According to author Rob Young, a huge argument between Hardin and Can occurred after the London concert, during which Hardin threw a television set through a car's windscreen (or windshield).[9]

On December 29, 1980, Hardin was found on the floor of his Hollywood apartment by longtime friend Ron Daniels. He died of a heroin overdose. His remains were buried in Twin Oaks Cemetery in Turner, Oregon.[10]

Discography

- Tim Hardin 1 (1966)

- Tim Hardin 2 (1967)

- This Is Tim Hardin (1967)

- Tim Hardin 3 Live in Concert (1968)

- Tim Hardin 4 (1969)

- Suite for Susan Moore and Damion: We Are One, One, All in One[11] (1969)

- Bird on a Wire (1971)

- Painted Head (1972)

- Nine (1973)

- Unforgiven (1981)

References

- HARDIN, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 243. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- Brend, Mark (2001). American Troubadours: Groundbreaking Singer-Songwriters of the '60s. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-87930-641-0.

- "Tim Hardin Biography". Zipcon.net. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Richie Unterberger. "Tim Hardin | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Richie Unterberger. "lovin.html". Richieunterberger.com. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Tim Hardin Contracts Pleurisy", Rolling Stone, No. 16, August 24, 1968, p.5

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Young, Rob & Schmidt, Irmin "All Gates Open: The Story of Can", Faber & Faber, 2018, ISBN 978-0-571-31149-1, pp. 257-258).

- Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. p. 364. ISBN 9780879728212.

- Richie Unterberger. "Suite for Susan Moore and Damion: We Are One, One, All in One - Tim Hardin | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

External links

- Tim Hardin at IMDb

- Tim Hardin at Find a Grave

- Detailed fan site

- Woodstock performance--If I Were a Carpenter