Eugene, Oregon

Eugene (/juːˈdʒiːn/ yoo-JEEN) is a city in the U.S. state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest. It is at the southern end of the verdant Willamette Valley, near the confluence of the McKenzie and Willamette rivers, about 50 miles (80 km) east of the Oregon Coast.[7]

Eugene, Oregon | |

|---|---|

| City of Eugene | |

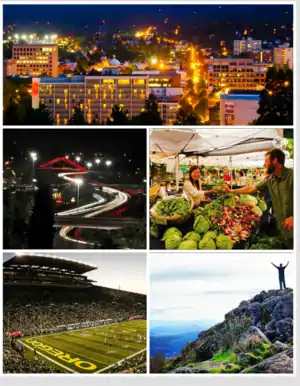

Clockwise: Downtown Eugene from Skinner Butte, Lane County Farmers' Market, Hiking on Spencer Butte, University of Oregon Autzen Stadium, Delta Ponds pedestrian bridge | |

Seal | |

| Nicknames: Emerald Valley, The Emerald City, Track Town | |

| Motto(s): A Great City for the Arts and Outdoors | |

| |

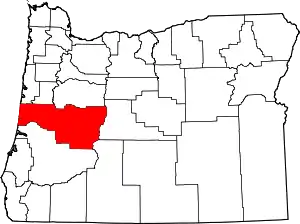

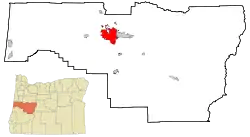

Eugene Location within Oregon  Eugene Location within the United States  Eugene Eugene (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 44°03′07″N 123°05′12″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Lane |

| Founded | 1846 |

| Incorporated | October 17, 1862 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Lucy Vinis (D) |

| • City manager | Sarah Medary |

| Area | |

| • City | 44.21 sq mi (114.50 km2) |

| • Land | 44.14 sq mi (114.32 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.18 km2) |

| Elevation | 430 ft (131 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 156,185 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 172,622 |

| • Rank | US: 155th |

| • Density | 3,910.87/sq mi (1,509.98/km2) |

| • Urban | 247,421 (US: 151st) |

| • Metro | 374,748 (US: 141st) |

| Demonym(s) | Eugenean[4][5] |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 97401–97405, 97408, 97440 |

| Area code(s) | 458 and 541 |

| FIPS code | 41-23850 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1120527[6] |

| Website | www.eugene-or.gov |

As of the 2010 census, Eugene had a population of 156,185; it is the county seat of Lane County and the state's third most populous city after Portland and Salem, though recent state estimates suggest its population may have surpassed Salem's.[8][9] The Eugene-Springfield, Oregon metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is the 146th largest metropolitan statistical area in the US and the third-largest in the state, behind the Portland Metropolitan Area and the Salem Metropolitan Area.[10] The city's population for 2019 was estimated to be 172,622 by the U.S. Census.[11]

Eugene is home to the University of Oregon, Bushnell University, and Lane Community College.[12][13][14] Several spots within Eugene are believed to be inspiration for locations in The Simpsons. This includes Max's Tavern and the Oregon Pioneer statue on campus.[15] The city is noted for its natural environment, recreational opportunities (especially bicycling, running/jogging, rafting, and kayaking), and focus on the arts, along with its history of civil unrest, protests, and green activism. Eugene's official slogan is "A Great City for the Arts and Outdoors".[16] It is also referred to as the "Emerald City" and as "Track Town, USA".[17] The Nike corporation had its beginnings in Eugene.[18] In 2022, the city will host the 18th Track and Field World Championships.[19]

History

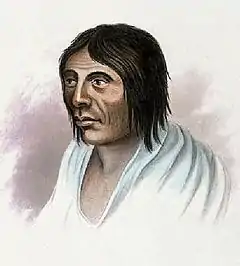

Indigenous presence

The first people to settle in the Eugene area were known as the Kalapuyans, also written Calapooia or Calapooya. They made "seasonal rounds," moving around the countryside to collect and preserve local foods, including acorns, the bulbs of the wapato and camas plants, and berries. They stored these foods in their permanent winter village. When crop activities waned, they returned to their winter villages and took up hunting, fishing, and trading.[20][21] They were known as the Chifin Kalapuyans and called the Eugene area where they lived "Chifin", sometimes recorded as "Chafin" or "Chiffin".[22][23]

Other Kalapuyan tribes occupied villages that are also now within Eugene city limits. Pee-you or Mohawk Calapooians, Winefelly or Pleasant Hill Calapooians, and the Lungtum or Long Tom. They were close-neighbors to the Chifin, intermarried, and were political allies. Some authorities suggest the Brownsville Kalapuyans (Calapooia Kalapuyans) were related to the Pee-you. It is likely that since the Santiam had an alliance with the Brownsville Kalapuyans that the Santiam influence also went as far at Eugene.[24]

According to archeological evidence, the ancestors of the Kalapuyans may have been in Eugene for as long as 10,000 years.[25] In the 1800s their traditional way of life faced significant changes due to devastating epidemics and settlement, first by French fur traders and later by an overwhelming number of American settlers[26]

Settlement and impact

French fur traders had settled seasonally in the Willamette Valley by the beginning of the 19th century. Their settlements were concentrated in the "French Prairie" community in Northern Marion County but may have extended south to the Eugene area. Having already developed relationships with Native communities through intermarriage and trade, they negotiated for land from the Kalapuyans. By 1828 to 1830 they and their Native wives began year-round occupation of the land, raising crops and tending animals. In this process, the mixed race families began to impact Native access to land, food supply, and traditional materials for trade and religious practices.[27]

In July 1830, "intermittent fever" struck the lower Columbia region and a year later, the Willamette Valley. Natives traced the arrival of the disease, then new to the Northwest, to the U.S. ship, Owyhee, captained by John Dominis. "Intermittent fever" is thought by researchers now to be malaria.[28] According to Robert T. Boyd, an anthropologist at Portland State University, the first three years of the epidemic, "probably constitute the single most important epidemiological event in the recorded history of what would eventually become the state of Oregon". In his book The Coming of the Spirit Pestilence Boyd reports there was a 92% population loss for the Kalapuyans between 1830 and 1841.[29] This catastrophic event shattered the social fabric of Kalapuyan society and altered the demographic balance in the Valley. This balance was further altered over the next few years by the arrival of Anglo-American settlers, beginning in 1840 with 13 people and growing steadily each year until within 20 years more than 11,000 American settlers, including Eugene Skinner, had arrived.[30]

As the demographic pressure from the settlers grew, the remaining Kalapuyans were forcibly removed to Indian reservations. Though some Natives escaped being swept into the reservation, most were moved to the Grand Ronde reservation in 1856.[31][32] Strict racial segregation was enforced and mixed race people, known as Métis in French, had to make a choice between the reservation and Anglo society. Native Americans could not leave the reservation without traveling papers and white people could not enter the reservation.[33]

Eugene Franklin Skinner, after whom Eugene is named, arrived in the Willamette Valley in 1846 with 1,200 other settlers that year. Advised by the Kalapuyans to build on high ground to avoid flooding, he erected the first Anglo cabin[34] on south or west slope of what the Kalapuyans called Ya-po-ah. The "isolated hill" is now known as Skinner's Butte.[35] The cabin was used as a trading post and was registered as an official post office on January 8, 1850.

At this time the settlement was known by Anglos as Skinner's Mudhole. It was relocated in 1853 and named Eugene City in 1853.[36] Formally incorporated as a city in 1862, it was named simply Eugene in 1889.[37][36] Skinner ran a ferry service across the Willamette River where the Ferry Street Bridge now stands.

Educational institutions

The first major educational institution in the area was Columbia College, founded a few years earlier than the University of Oregon. It fell victim to two major fires in four years, and after the second fire, the college decided not to rebuild again.[38] The part of south Eugene known as College Hill was the former location of Columbia College. There is no college there today.[39]

The town raised the initial funding to start a public university, which later became the University of Oregon, with the hope of turning the small town into a center of learning. In 1872, the Legislative Assembly passed a bill creating the University of Oregon as a state institution. Eugene bested the nearby town of Albany in the competition for the state university. In 1873, community member J.H.D. Henderson donated the hilltop land for the campus, overlooking the city.[40]

The university first opened in 1876 with the regents electing the first faculty and naming John Wesley Johnson as president. The first students registered on October 16, 1876. The first building was completed in 1877; it was named Deady Hall in honor of the first Board of Regents President and community leader Judge Matthew P. Deady.[41]

Twentieth century

Eugene grew rapidly throughout most of the twentieth century, with the exception being the early 1980s when a downturn in the timber industry caused high unemployment. By 1985, the industry had recovered and Eugene began to attract more high-tech industries, earning it the moniker the "Emerald Shire".

The first Nike shoe was used in 1972 during the US Olympic trials held in Eugene.[42]

History of civil unrest

Eugene has a long history of community activism, civil unrest, and protest activity.[43] Eugene's cultural status as a place for alternative thought grew along with the University of Oregon in the turbulent 1960s, and its reputation as an outsider's locale grew with the numerous anarchist protests in the late 1990s. In 2000, the Chicago Tribune described the city as a “cradle to [the] latest generation of anarchist protesters.”[44] Occupy Eugene was home to one of the nation's longest-lasting Occupy protests in 2011, with the last protestor leaving the initial Occupy camp on December 27, 2011.[45] The city received national attention during the summer of 2020, after Black Lives Matter protests in response to the killing of George Floyd grew violent.[46]

1960s: Counterculture and campus protests

Already a counter-culture haven, Eugene felt the change of the 1960s in a heavy way, with underground groups carrying out bombings on military targets. In September 1967, the Eugene Naval & Marine Corps Reserve Training Center was damaged by a series of explosions and fire, and in November 1967, a bomb exploded at the Air Force ROTC building.[43] On Sept 30, 1968, unknown anti-capitalists exploded firebombs at the Eugene Armory, causing over $100,000 in damage (approximately $741,000 in 2020), destroying multiple trucks and Jeeps and dealing significant destruction to the city's equipment compound.[47] Unrest continued throughout 1969 as well, with frequent dynamite attacks on local businesses, newspapers, and Emerald Hall on the University of Oregon campus.[48]

Student activism at the university shaped both campus and Eugene life during the times of social upheaval. Protests at the University of Oregon were the most intensely heated against the Oregon chapter of the ROTC, which was the embodiment of the war effort in Vietnam and Cambodia.[49] The UO chapter of Students for a Democratic Society formed in 1965 but came to the forefront of campus activity in 1969, when they first led students to march and demand the removal of campus ROTC. On January 6, 1970, campus demonstrators threw animal blood onto tables at an ROTC recruitment event in order to draw attention to the barbaric war in Vietnam.[49] Students held a public "People's Trial" of campus president Robert D. Clark, finding him guilty for "complicity in the actions of U.S. imperialism" by enabling the Oregon ROTC to have a presence on campus.

Throughout January and February 1970, anti-war student activists disrupted ROTC events and demonstrated against the war presence, culminating in unknown perpetrators setting the University of Oregon ROTC building on fire in Esslinger Hall, causing massive damage and destroying draft records of university students.[49] In March, 150-200 students, led by the campus SDS chapter, attempted to gain entry to McArthur Court for a concert, setting off a riot that resulted in the arrest of 5 students. On April 15, 1970, the UO faculty voted by a 199-185 margin to allow the ROTC to remain on campus, which immediately led to nearly 100 students ransacking the ROTC building, breaking furniture, windows, and throwing rocks at the property, to which the police used tear gas on campus demonstrators for the first time.[49]

The height of the Vietnam protest movement at UO occurred over three days between April 22 and April 24, 1970. At 11:00 am on the 22nd, between 50 and 100 UO students occupied Johnson Hall to protest the ROTC’s continued presence on campus, taking over the lobby of the building. The crowd grew to around 300 students by 5:00 pm, when Clark negotiated with the group to allow the protestors to remain in the lobby overnight if they remained peaceful.[49] The protests disrupted work and on the 24th, Eugene police arrived, arresting 61 protestors, but everything remained peaceful until the National Guard arrived on the scene and escalated the situation by deploying tear gas against the crowd outside the building. News of the National Guard’s involvement led a larger congregation of nearly 2000 students to converge at Emerald Hall in protest of the incident.[49]

On April 26, 1970, around 40 UO students successfully closed 13th Avenue through the university by erecting barricades on either end, calling it "People's Street". This protest successfully forced the Eugene City Council to hold hearings on restricting the street to non-automobile traffic, which passed and soon went into effect.[49] On October 2, 1970, unidentified perpetrators exploded a bomb in Prince Lucien Hall, causing $75,000 in damage (approximately $511,000 in 2020).[50]

1970s activism

The 1970s saw an increase in community activism. Local activists stopped a proposed freeway and lobbied for the construction of the Washington Jefferson Park beneath the Washington-Jefferson Street Bridge. Community Councils soon began to form as a result of these efforts.[51] A notable impact of the turn to community-organized politics came with Eugene Local Measure 51, a ballot measure in 1978 that repealed a gay rights ordinance approved by the Eugene City Council in 1977 that prohibited discrimination by sexual orientation.

1990s: Anarchist activity

Eugene's constant ability for protest capabilities were made clear at the beginning of the decade. In January 1991, a downtown student-led protest against the Gulf War drew 1,500 people and resulted in the arrest of 51, including 15 juveniles.[52] Protesters carried a 10-year-old girl inside a body bag to the front door of the federal building as a symbol of war's innocent deaths.[53] After the demonstration, a fire was set at a Eugene Marine Corps recruiting station.[54]

Attempts by the city to remove a forest grove at downtown Broadway and Charnelton were met with protests on June 1, 1997. Forty trees in downtown Eugene were cut down to make way for a parking garage project and were met with community resistance. 22 people were arrested and the Register-Guard ran a front-page photograph showing a photographer being sprayed with pepper spray by the police.[55] The Eugene force was accused of overreaction and excessive use of force for their flagrant use of pepper spray, which was defended by Republican mayor Jim Torrey.[56] In the Whitaker District, citizens were further radicalized by the incident and helped spur the activist community, which was already burgeoning due to a lack of affordable housing and growing income inequality in the area.[57]

On June 18, 1999, several months before the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, Eugene was home to a predecessor riot. Following a two-day conference at the University of Oregon about the dissolution of the country's economic system, a rally against global capitalism enveloped the streets of the downtown area. After the rally, protestors turned to the streets, stopping traffic, burning flags, and smashing windows and electronic equipment.[58] After police responded with tear gas and pepper spray, protesters battled with police for several hours. The tear gas used by the Eugene police affected over 100 people, and 15 were arrested.[58] Later that year, Eugene activists also played a key role in conjunction with other anarchists in organizing black bloc tactics during the World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference of 1999 protest activity.[59] Eugene police subsequently claimed that local anarchists were responsible for other attacks on local police officers.[57] Local activists in turn argued that police needlessly harassed individuals wearing black clothing in response.[57]

Mayor Jim Torrey declared Eugene to be the "Anarchist Capital of the World" in response to the riots, which some embraced.[60] Seattle police chief Norm Stamper in his resignation speech after the 1999 WTO protests blamed the majority of the unrest on "Eugene anarchists".[61] Influential thinkers in Eugene's scene at the time included John Zerzan, an author known for his contributions to leftist theory and who was an editor for Green Anarchy, an anarchist magazine based in the city. Anarchists and leftists continued to protest against Torrey throughout his tenure, including gathering each June 1 (the anniversary of the Broadway Place confrontations) to protest against police brutality committed under his control.[62]

One hotspot for protest activity since the 1990s has been the Whitaker district, located in the northwest of downtown Eugene. Whitaker is primarily a working-class neighborhood that has become a vibrant cultural hub, center of community and activism and home to alternative artists. It saw an increase of activity in the 1990s after many young people drawn to Eugene's political climate relocated there.[57] Animal rights groups have had a heavy presence in the Whiteaker, and several vegan restaurants are located there. According to David Samuels, the Animal Liberation Front and the Earth Liberation Front have had an underground presence in the neighborhood.[63] The neighborhood is home to a number of communal apartment buildings, which are often organized by anarchist or environmentalist groups. Local activists have also produced independent films and started art galleries, community gardens, and independent media outlets. Copwatch, Food Not Bombs, and Critical Mass are also active in the neighborhood.[64]

21st century unrest

The more visible anarchist scene seemed to have died down after an upswing of several years, but protest activity still remained in Eugene.[60] Groups such as the Neighborhood Anarchist Collective still maintained an active grassroots network, and the Eugene Share Fair has been used as a resource for organizations to market support.[60] On June 16, 2000, environmental activists set fire to trucks at a car dealership on Franklin Boulevard.[61] On the one-year anniversary of the 1999 riots, police again attacked demonstrators, arresting 37 and striking a KLCC reporter on the head with a baton. Later, while anarchism took a backseat, Eugene's reputation as a potent leftist center increased as overall political support in the city swung liberally.[65]

Occupy Eugene

The Occupy Eugene protests grew out of the Occupy Wall Street movement which began in New York City on September 17, 2011. The Eugene protesters were concerned about fairness issues regarding wealth-distribution, banking regulation, housing issues and corporate greed.[66] The first protest march was held on October 15, 2011 and the main encampment, located in Washington Jefferson Park lasted until December 2011. The initial Occupy Eugene demonstrations had over 2,000 attendees and began at Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza.[67]

2020 George Floyd protests

Eugene's George Floyd/Black Lives Matter protests grew out of the civil unrest that began in Minneapolis and spread nationwide in May 2020 after the killing of Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer.

In Eugene, demonstrators turned their attention to surrounding stores on May 29, and disrupted traffic and knocked trash and newsstands into the street in the downtown. Rioters crowded on to Highway I-105 and began setting fire to a nearby road sign.[68] That night, fires were set and windows were smashed. Around 11 p.m., protestors created a bonfire in the street, consisting of traffic cones, newspapers, signs from local businesses, and other items.[69] No arrests were made on that night.[70]

Protests - including marches, rallies, and teach-ins - continued daily for several weeks, re-igniting in response to the insertion of federal troops in Portland.[71]

On June 13 protesters toppled the Pioneer and the Pioneer Mother during a protest of Matthew Deady (controversially the namesake of a University of Oregon building).[72]

Over 2,000 demonstrators attended a Juneteenth Black Lives Matter protest at Alton Baker Park, which was designed to draw revenue to Black-owned businesses.[73]

Environmental activism

On October 14, 1996, to commemorate the anniversary of Columbus Day, Earth Liberation Front activists coordinated several attacks on local fast food chains and oil companies. Two Willamette Chevron gas station locks were glued and painted with the slogan "504 Years of Genocide" and "Earth Liberation Front". Two Eugene public relation offices of Weyerhauser and Hyundai were also targeted in a similar manner.[74] Later in the month, ELF protestors destroyed a U.S. Forest Service Ranger Station south of Eugene, causing an estimated damage of $5.3 million. These were some of the first examples of eco-defense in the United States.[74]

In September 2000, members of a Eugene-based cell of the ELF burnt down the Eugene Police Department's West University Public Safety Station. Later, in March 2001, activists attacked the same car dealership on Franklin for the second time in 6 months, damaging more than 30 SUVs.[61] Over 125 different fire attacks were set in the city between 1997 and 2001.[75]

In January 2006, the FBI conducted Operation Backfire, leading to federal indictment of eleven people, all members of ELF.[76] Operation Backfire was the largest investigation into radical underground environmental groups in United States history.[77] Ongoing trials of accused eco-terrorists kept Eugene in the spotlight for a few years.[78]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 43.74 square miles (113.29 km2), of which 43.72 square miles (113.23 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.05 km2) is water.[79] Eugene is at an elevation of 426 feet (130 m).

To the north of downtown is Skinner Butte. Northeast of the city is the Coburg Hills. Spencer Butte is a prominent landmark south of the city. Mount Pisgah is southeast of Eugene and includes Mount Pisgah Arboretum and Howard Buford Recreation Area, a Lane County Park. Eugene is surrounded by foothills and forests to the south, east, and west, while to the north the land levels out into the Willamette Valley and consists of mostly farmland.

The Willamette and McKenzie Rivers run through Eugene and its neighboring city, Springfield. Another important stream is Amazon Creek, whose headwaters are near Spencer Butte. The creek discharges west of the city into Fern Ridge Reservoir, maintained for winter flood control by the Army Corps of Engineers. The Eugene Yacht Club hosts a sailing school and sailing regattas at Fern Ridge during summer months.[80]

Neighborhoods

Eugene has 23[81] neighborhood associations:

- Amazon

- Bethel

- Cal Young

- Churchill

- Crest Drive

- Downtown

- Fairmount

- Far West

- Friendly

- Goodpasture Island

- Harlow

- Industrial Corridor

- Jefferson Westside

- Laurel Hill Valley

- Northeast

- River Road

- Santa Clara (including Irving)

- South University

- Southeast

- Spencer Butte

- Trainsong

- West Eugene

- West University

- Whiteaker

Climate

| Eugene | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like the rest of the Willamette Valley, Eugene lies in the Marine West Coast climate zone, with Mediterranean characteristics. Under the Köppen climate classification scheme, Eugene has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb). Temperatures can vary from cool to warm, with warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters. Spring and fall are also moist seasons, with light rain falling for long periods. The average rainfall is 46.1 inches or 1,170.9 millimetres, with the wettest "rain year" being from July 1973 to June 1974 with 75.59 inches (1,920.0 mm) and the driest from July 2000 to June 2001 with 20.40 inches (518.2 mm).[82] Winter snowfall does occur, but it is sporadic and rarely accumulates in large amounts: the normal seasonal amount is 4.9 inches or 0.12 metres, but the median is zero.[82] The record snowfall was 41.7 inches or 1.06 metres of accumulation due to a pineapple express on January 25–29, 1969.[82] Ice storms, like snowfall, are rare, but occur sporadically.

The hottest months are July and August, with a normal monthly mean temperature of 66.8 to 66.9 °F (19.3 to 19.4 °C), with an average of 16 days per year reaching 90 °F or 32.2 °C. The coolest month is December, with a mean temperature of 39.7 °F (4.3 °C), and there are 53 mornings per year with a low at or below freezing, and 2.7 afternoons with highs not exceeding the freezing mark.[82]

Eugene's average annual temperature is 52.5 °F (11.4 °C), and annual precipitation at 46.1 inches (1,170 mm).[83] Eugene is more wet and slightly cooler on average than Portland. Despite being about 100 miles (160 km) south and having only a slightly higher elevation, Eugene has a more continental climate, less subject to the maritime air that blows inland from the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River. Eugene's normal annual mean minimum is 41.6 °F (5.3 °C),[82] compared to 45.7 °F (7.6 °C) in Portland;[84] in August, the gap in the normal mean minimum widens to 51.1 °F (10.6 °C) and 58.0 °F (14.4 °C) for Eugene and Portland, respectively.[82] Average winter temperatures (and summer high temperatures) are similar for the two cities. This disparity may be additionally caused by Portland's urban heat island, where the combination of black pavement and urban energy use raises nighttime temperatures.

Extreme temperatures range from −12 °F (−24 °C), recorded on December 8, 1972, to 108 °F (42 °C) on August 9, 1981; the record cold daily maximum is 19 °F (−7 °C), recorded on December 13, 1919, while, conversely, the record warm daily minimum is 71 °F (22 °C) on July 22, 2006.[82]

| Climate data for Eugene Airport, Oregon (1981–2010 normals,[85] extremes 1892–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

78 (26) |

80 (27) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

103 (39) |

94 (34) |

76 (24) |

68 (20) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 59.4 (15.2) |

62.8 (17.1) |

68.7 (20.4) |

76.3 (24.6) |

84.0 (28.9) |

89.7 (32.1) |

97.0 (36.1) |

96.9 (36.1) |

91.9 (33.3) |

78.9 (26.1) |

64.4 (18.0) |

58.8 (14.9) |

100.1 (37.8) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.2 (8.4) |

51.1 (10.6) |

56.2 (13.4) |

60.8 (16.0) |

67.0 (19.4) |

73.2 (22.9) |

82.3 (27.9) |

82.8 (28.2) |

76.9 (24.9) |

64.2 (17.9) |

52.2 (11.2) |

45.6 (7.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 40.7 (4.8) |

42.9 (6.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

50.2 (10.1) |

55.3 (12.9) |

60.4 (15.8) |

66.8 (19.3) |

66.9 (19.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

52.7 (11.5) |

44.9 (7.2) |

39.7 (4.3) |

52.4 (11.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 34.2 (1.2) |

34.8 (1.6) |

37.1 (2.8) |

39.5 (4.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

51.4 (10.8) |

51.1 (10.6) |

47.0 (8.3) |

41.2 (5.1) |

37.6 (3.1) |

33.8 (1.0) |

41.6 (5.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

34.2 (1.2) |

38.6 (3.7) |

43.6 (6.4) |

43.0 (6.1) |

37.5 (3.1) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

16.7 (−8.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

−3 (−19) |

18 (−8) |

25 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

32 (0) |

39 (4) |

35 (2) |

30 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

12 (−11) |

−10 (−23) |

−10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.87 (174) |

5.43 (138) |

4.99 (127) |

3.33 (85) |

2.74 (70) |

1.50 (38) |

0.54 (14) |

0.61 (15) |

1.29 (33) |

3.25 (83) |

7.72 (196) |

7.83 (199) |

46.10 (1,171) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.8 (2.0) |

2.4 (6.1) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.5 (3.8) |

4.9 (12) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.9 | 14.9 | 17.7 | 14.5 | 11.7 | 7.9 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 143.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 3.0 |

| Source: NOAA[82][83] | |||||||||||||

Air quality and allergies

Eugene is downwind of Willamette Valley grass seed farms.[86] The combination of summer grass pollen and the confining shape of the hills around Eugene make it "the area of the highest grass pollen counts in the USA (>1,500 pollen grains/m3 of air)."[87] These high pollen counts have led to difficulties for some track athletes who compete in Eugene. In the Olympic trials in 1972, "Jim Ryun won the 1,500 after being flown in by helicopter because he was allergic to Eugene's grass seed pollen."[88] Further, six-time Olympian Maria Mutola abandoned Eugene as a training area "in part to avoid allergies".[89]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,183 | — | |

| 1870 | 861 | −27.2% | |

| 1880 | 1,117 | 29.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,236 | — | |

| 1910 | 9,009 | 178.4% | |

| 1920 | 10,593 | 17.6% | |

| 1930 | 18,901 | 78.4% | |

| 1940 | 20,838 | 10.2% | |

| 1950 | 35,879 | 72.2% | |

| 1960 | 50,977 | 42.1% | |

| 1970 | 79,028 | 55.0% | |

| 1980 | 105,664 | 33.7% | |

| 1990 | 112,669 | 6.6% | |

| 2000 | 137,893 | 22.4% | |

| 2010 | 156,185 | 13.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 172,622 | [3] | 10.5% |

| Sources:[90][91] | |||

2010 census

According to the 2010 census, Eugene's population was 156,185.[8] The population density was 3,572.2 people per square mile. There were 69,951 housing units at an average density of 1,600 per square mile.[92] Those age 18 and over accounted for 81.8% of the total population.[92]

The racial makeup of the city was 85.8% White, 4.0% Asian, 1.4% Black or African American, 1.0% Native American, 0.2% Pacific Islander, and 4.7% from other races.[92]

Hispanics and Latinos of any race accounted for 7.8% of the total population.[93] Of the non-Hispanics, 82% were White, 1.3% Black or African American, 0.8% Native American, 4% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 0.2% some other race alone, and 3.4% were of two or more races.[92]

Females represented 51.1% of the total population, and males represented 48.9%. The median age in the city was 33.8 years.[94]

2000 census

The census of 2000 showed there were 137,893 people, 58,110 households, and 31,321 families residing in the city of Eugene. The population density was 3,404.8 people per square mile (1,314.5/km2). There were 61,444 housing units at an average density of 1,516.4 per square mile (585.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.15% White, down from 99.5% in 1950,[95] 3.57% Asian, 1.25% Black or African American, 0.93% Native American, 0.21% Pacific Islander, 2.18% from other races, and 3.72% from two or more races. 4.96% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 58,110 households, of which 25.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.6% were married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.1% were non-families. 31.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.87. In the city, the population was 20.3% under the age of 18, 17.3% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 12.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.0 males. The median income for a household in the city was $35,850, and the median income for a family was $48,527. Males had a median income of $35,549 versus $26,721 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,315. About 8.7% of families and 17.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.8% of those under age 18 and 7.1% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Eugene's largest employers are PeaceHealth Medical Group, the University of Oregon, and the Eugene School District.[96] Eugene's largest industries are wood products manufacturing and recreational vehicle manufacturing.[97]

Luckey's Club Cigar Store is one of the oldest bars in Oregon. Tad Luckey, Sr., purchased it in 1911, making it one of the oldest businesses in Eugene. The "Club Cigar", as it was called in the late 19th century, was for many years a men-only salon. It survived both the Great Depression and Prohibition, partly because Eugene was a dry town before the end of Prohibition.[98]

Corporate headquarters for the employee-owned Bi-Mart corporation and family-owned supermarket Market of Choice remain in Eugene.

The city has over 25 breweries, offers a variety of dining options with a local focus; the city is surrounded by wineries. The most notable fungi here is the truffle; Eugene hosts the annual Oregon Truffle Festival in January.[99]

Organically Grown Company, the largest distributor of organic fruits and vegetables in the northwest, started in Eugene in 1978 as a non-profit co-op for organic farmers. Notable local food processors, many of whom manufacture certified organic products, include Golden Temple (Yogi Tea), Merry Hempsters and Springfield Creamery (Nancy's Yogurt & owned by the Kesey Family), and Mountain Rose Herbs.

Until July 2008, Hynix Semiconductor America had operated a large semiconductor plant in west Eugene. In late September 2009, Uni-Chem of South Korea announced its intention to purchase the Hynix site for solar cell manufacturing.[100] However, this deal fell through and as of late 2012, is no longer planned.[101] In 2015, semiconductor manufacturer Broadcom purchased the plant with plans to upgrade and reopen it. The company abandoned these plans and put it up for sale in November 2016.[102]

The footwear repair product Shoe Goo is manufactured by Eclectic Products, based in Eugene.

Run Gum, an energy gum created for runners, also began its life in Eugene. Run Gum was created by track athlete Nick Symmonds and track and field coach Sam Lapray in 2014.[103]

Burley Design LLC produces bicycle trailers and was founded in Eugene by Alan Scholz out of a Saturday Market business in 1978. Eugene is also the birthplace and home of Bike Friday bicycle manufacturer Green Gear Cycling.

Many multinational businesses were launched in Eugene. Some of the most famous include Nike,[18] Taco Time,[104] and Brøderbund Software.[105]

In 2012, the Eugene metro region was dubbed the Silicon Shire for its growing tech industry.

Top employers

According to Eugene's 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[106] the city's top employers are:

| # | Employer | Number of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PeaceHealth Medical Group | 5,808 |

| 2 | University of Oregon | 5,549 |

| 3 | Eugene School District 4J | 2,553 |

| 4 | U.S. Government | 1,750 |

| 5 | Lane Community College | 1,650 |

| 6 | Springfield School District | 1,610 |

| 7 | State of Oregon | 1,594 |

| 8 | Lane County | 1,567 |

| 9 | City of Eugene | 1,417 |

| 10 | McKenzie-Willamette Medical Center | 898 |

Arts and culture

Eugene has a significant population of people in pursuit of alternative ideas and a large original hippie population.[107] Beginning in the 1960s, the countercultural ideas and viewpoints espoused by Ken Kesey became established as the seminal elements of the vibrant social tapestry that continue to define Eugene.[108] The Merry Prankster, as Kesey was known, has arguably left the most indelible imprint of any cultural icon in his hometown. He is best known as the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and as the male protagonist in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.[108]

In 2005, the city council unanimously approved a new slogan for the city: "World's Greatest City for the Arts & Outdoors". While Eugene has a vibrant arts community for a city its size, and is well situated near many outdoor opportunities, this slogan was frequently criticized by locals as embarrassing and ludicrous.[109] In early 2010, the slogan was changed to "A Great City for the Arts & Outdoors."

Eugene's Saturday Market, open every Saturday from April through November,[110] was founded in 1970 as the first "Saturday Market" in the United States.[111] It is adjacent to the Lane County Farmer's Market in downtown Eugene. All vendors must create or grow all their own products. The market reappears as the "Holiday Market" between Thanksgiving and New Year's in the Lane County Events Center at the fairgrounds.

Community

Eugene is noted for its "community inventiveness." Many U.S. trends in community development originated in Eugene. The University of Oregon's participatory planning process, known as The Oregon Experiment, was the result of student protests in the early 1970s. The book of the same name is a major document in modern enlightenment thinking in planning and architectural circles. The process, still used by the university in modified form, was created by Christopher Alexander, whose works also directly inspired the creation of the Wiki. Some research for the book A Pattern Language, which inspired the Design Patterns movement and Extreme Programming, was done by Alexander in Eugene. Not coincidentally, those engineering movements also had origins here. Decades after its publication, A Pattern Language is still one of the best-selling books on urban design.[112]

In the 1970s, Eugene was packed with cooperative and community projects. It still has small natural food stores in many neighborhoods, some of the oldest student cooperatives in the country, and alternative schools have been part of the school district since 1971. The old Grower's Market, downtown near the Amtrak depot, is the only food cooperative in the U.S. with no employees. It is possible to see Eugene's trend-setting non-profit tendencies in much newer projects, such as the Tango Center and the Center for Appropriate Transport. In 2006, an initiative began to create a tenant-run development process for downtown Eugene.

In the fall of 2003, neighbors noticed "an unassuming two-acre remnant orchard tucked into the Friendly Area Neighborhood"[113] had been put up for sale by its owner, a resident of New York City.[114] Learning a prospective buyer had plans to build several houses on the property, they formed a nonprofit organization called Madison Meadow[115][116] in June 2004 in order to buy the property and "preserve it as undeveloped space in perpetuity."[115] In 2007 their effort was named Third Best Community Effort by the Eugene Weekly,[117] and by the end of 2008 they had raised enough money to purchase the property.[113]

The City of Eugene has an active Neighborhood Program. Several neighborhoods are known for their green activism. Friendly Neighborhood has a highly popular neighborhood garden established on the right of way of a street never built. There are a number of community gardens on public property. Amazon Neighborhood has a former church turned into a community center. Whiteaker hosts a housing co-op that dates from the early 1970s that has re-purposed both their parking lots into food production and play space. An unusual eco-village with natural building techniques and large shared garden can be found in Jefferson Westside neighborhood. A several block area in the River Road Neighborhood is known as a permaculture hotspot with an increasing number of suburban homes trading grass for garden, installing rain water catchment systems, food producing landscapes and solar retrofits. Several sites have planted gardens by removing driveways. Citizen volunteers are working with the City of Eugene to restore a 65-tree filbert grove on public property. There are deepening social and economic networks in the neighborhood.

Annual cultural events

- Asian Celebration,[118] presented by the Asian Council of Eugene and Springfield, takes place in February at the Lane County Fairgrounds.

- The KLCC Microbrew Festival[119] is held in February at the Lane County Fairgrounds. It provides participants with an introduction to a large range of microbrewery and craft beers, which play an important role in Pacific Northwest culture and the economy.[120][119]

- Mount Pisgah Arboretum, which resides at the base of Mount Pisgah, holds a Wildflower Festival in May and a Mushroom Festival and Plant Sale in October.[121]

- Oregon Festival of American Music,[122] or OFAM is held annually in the early summer.

- Art and the Vineyard[123] festival, held around the Fourth of July at Alton Baker Park, is the principal fundraiser for the Maude Kerns Art Center.[124]

- The Oregon Bach Festival is a major international festival in July,[125] hosted by the University of Oregon.[126]

- The nonprofit Oregon Country Fair[127] takes place in July in nearby Veneta.

- The Lane County Fair[128] occurs in July at the Lane County Fairgrounds.

- The Eugene/Springfield Pride Festival[129] is held annually on the second Saturday in August from noon to 7:00 p.m. at Alton Baker Park. A part of Eugene LGBT culture since 1993, it provides a lighthearted and supportive social venue for the LGBT community, families, and friends.

- Eugene Celebration[130] is a three-day block party that usually takes place in the downtown area in August or September. The SLUG Queen coronation in August, a pageant with a campy spin, crowns a new SLUG Queen who "rains" over the Eugene Celebration Parade and is an unofficial ambassador of Eugene.[131]

Museums

Eugene museums include the University of Oregon's Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art and Museum of Natural and Cultural History, the Oregon Air and Space Museum, Lane County History Museum,[132] Maude Kerns Art Center, Shelton McMurphey Johnson House, and the Eugene Science Center.

Performing arts

Eugene is home to numerous cultural organizations, including the Eugene Symphony, the Eugene Ballet, the Eugene Opera, the Eugene Concert Choir, the Northwest Christian University Community Choir, the Oregon Mozart Players, the Oregon Bach Festival, the Oregon Children's Choir, the Eugene-Springfield Youth Orchestras, Ballet Fantastique and Oregon Festival of American Music. Principal performing arts venues include the Hult Center for the Performing Arts, The John G. Shedd Institute for the Arts ("The Shedd"), Matthew Knight Arena, Beall Concert Hall and the Erb Memorial Union ballroom on the University of Oregon campus, the McDonald Theatre, and W.O.W. Hall.

A number of live theater groups are based in Eugene, including Free Shakespeare in the Park, Oregon Contemporary Theatre, The Very Little Theatre, Actors Cabaret, LCC Theatre, Rose Children's Theatre, and University Theatre.[133] Each has its own performance venue.

Music

Because of its status as a college town, Eugene has been home to many music genres, musicians and bands, ranging from electronic dance music such as dubstep and drum and bass to garage rock, hip hop, folk and heavy metal. Eugene also has a growing reggae and street-performing bluegrass and jug band scene. Multi-genre act the Cherry Poppin' Daddies became a prominent figure in Eugene's music scene and became the house band at Eugene's W.O.W. Hall. In the late 1990s, their contributions to the swing revival movement propelled them to national stardom. Rock band Floater originated in Eugene as did the Robert Cray blues band. Doom metal band YOB is among the leaders of the Eugene heavy music scene.

Eugene is home to "Classical Gas" Composer and two-time Grammy award winner Mason Williams who spent his years as a youth living between his parents in Oakridge, Oregon and Oklahoma. Mason Williams puts on a yearly Christmas show at the Hult center for performing arts with a full orchestra produced by author, audio engineer and University of Oregon professor Don Latarski.[134]

Dick Hyman, noted jazz pianist and musical director for many of Woody Allen's films, designs and hosts the annual Now Hear This! jazz festival at the Oregon Festival of American Music (OFAM). OFAM and the Hult Center routinely draw major jazz talent for concerts.[135][136]

Eugene is also home to a large Zimbabwean music community. Kutsinhira Cultural Arts Center, which is "dedicated to the music and people of Zimbabwe," is based in Eugene.

Visual arts

Eugene's visual arts community is supported by over 20 private art galleries and several organizations, including Maude Kerns Art Center,[137] Lane Arts Council,[138] DIVA (the Downtown Initiative for the Visual Arts) and the Eugene Glass School.

In 2015 installations from a group of Eugene-based artists known as Light At Play were showcased in several events around the world as part of the International Year of Light, including displays at the Smithsonian and the National Academy of Sciences.[139][140]

Film

The Eugene area has been used as a filming location for several Hollywood films, most famously for 1978's National Lampoon's Animal House, which was also filmed in nearby Cottage Grove. John Belushi had the idea for the film The Blues Brothers during filming of Animal House when he happened to meet Curtis Salgado at what was then the Eugene Hotel.[141]

Getting Straight, starring Elliott Gould and Candice Bergen, was filmed at Lane Community College in 1969. As the campus was still under construction at the time, the "occupation scenes" were easier to shoot.[142]

The "Chicken Salad on Toast" scene in the 1970 Jack Nicholson movie Five Easy Pieces was filmed at the Denny's restaurant at the southern I-5 freeway interchange near Glenwood. Nicholson directed the 1971 film Drive, He Said in Eugene.

How to Beat the High Co$t of Living, starring Jane Curtin, Jessica Lange and Susan St. James, was filmed in Eugene in the fall of 1979. Locations visible in the film include Valley River Center (which is a driving force in the plot), Skinner Butte and Ya-Po-Ah Terrace, the Willamette River and River Road Hardware.

Several track and field movies have used Eugene as a setting and/or a filming location. Personal Best, starring Mariel Hemingway, was filmed in Eugene in 1982. The film centered on a group of women who are trying to qualify for the Olympic track and field team. Two track and field movies about the life of Steve Prefontaine, Prefontaine and Without Limits, were released within a year of each other in 1997–1998. Kenny Moore, Eugene-trained Olympic runner and co-star in Prefontaine, co-wrote the screenplay for Without Limits. Prefontaine was filmed in Washington because the Without Limits production bought out Hayward Field for the summer to prevent its competition from shooting there.[143] Kenny Moore also wrote a biography of Bill Bowerman, played in Without Limits by Donald Sutherland back in Eugene 20 years after he had appeared in Animal House. Moore had also had a role in Personal Best.

Stealing Time, a 2003 independent film, was partially filmed in Eugene. When the film premiered in June 2001 at the Seattle International Film Festival, it was titled Rennie's Landing after a popular bar near the University of Oregon campus. The title was changed for its DVD release. Zerophilia was filmed in Eugene in 2006.

Religion

Religious institutions of higher learning in Eugene include Bushnell University and New Hope Christian College. Bushnell University (formerly Northwest Christian University), founded in 1895, has ties with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). New Hope Christian College (formerly Eugene Bible College) originated with the Bible Standard Conference in 1915, which joined with Open Bible Evangelistic Association to create Open Bible Standard Churches in 1932. Eugene Bible College was started from this movement by Fred Hornshuh in 1925.[144]

There are two Eastern Orthodox Church parishes in Eugene: St John the Wonderworker Orthodox Christian Church in the Historic Whiteaker Neighborhood[145][146] and Saint George Greek Orthodox Church.[147]

There are six Roman Catholic parishes in Eugene as well: St. Mary Catholic Church,[148] St. Jude Catholic Church, St. Mark Catholic Church, St. Peter Catholic Church, St. Paul Catholic Church, and St. Thomas More Catholic Church.[149]

Eugene also has a Ukrainian Catholic Church named Nativity of the Mother of God.[150]

There is a mainline Protestant contingency in the city as well—such as the largest of the Lutheran Churches, Central Lutheran[151] near the U of O Campus and the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection.[152]

The Eugene area has a sizeable LDS Church presence, with three stakes, consisting of 23 congregations (wards and branches).[153] The Portland Oregon Temple is the nearest temple.[154]

The greater Eugene-Springfield area also has a Jehovah's Witnesses presence with five Kingdom Halls, several having multiple congregations in one Kingdom Hall.

The Reconstructionist Temple Beth Israel is Eugene's largest Jewish congregation.[155] It was also, for many decades, Eugene's only synagogue,[156][157] until Orthodox members broke away in 1992 and formed "Congregation Ahavas Torah".[158][159]

Eugene has a community of some 140 Sikhs, who have established a Sikh temple.[160]

The 340-member congregation of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Eugene (UUCE)[161] purchased the former Eugene Scottish Rite Temple in May 2010, renovated it, and began services there in September 2012.

Saraha Nyingma Buddhist Temple in Eugene[162] opened in 2012 in the former site of the Unitarian Universalist Church.

Sports

Eugene's Oregon Ducks are part of the Pac-12 Conference (Pac-12). American football is especially popular, with intense rivalries between the Ducks and both the Oregon State University Beavers and the University of Washington Huskies.[163] Autzen Stadium is home to Duck football, with a seating capacity of 54,000 but has had over 60,000 with standing room only.[164]

The basketball arena, McArthur Court, was built in 1926.[165] The arena was replaced by the Matthew Knight Arena in late 2010.[166]

For nearly 40 years, Eugene has been the "Track and Field Capital of the World." Oregon's most famous track icon is the late world-class distance runner Steve Prefontaine, who was killed in a car crash in 1975.

Eugene's jogging trails include Pre's Trail in Alton Baker Park, Rexius Trail, the Adidas Oregon Trail, and the Ridgeline Trail. Jogging was introduced to the U.S. through Eugene, brought from New Zealand by Bill Bowerman, who wrote the best-selling book "Jogging", and coached the champion University of Oregon track and cross country teams. During Bowerman's tenure, his "Men of Oregon" won 24 individual NCAA titles, including titles in 15 out of the 19 events contested. During Bowerman's 24 years at Oregon, his track teams finished in the top ten at the NCAA championships 16 times, including four team titles (1962, '64, '65, '70), and two second-place trophies. His teams also posted a dual meet record of 114–20.

Bowerman also invented the waffle sole for running shoes in Eugene, and with Oregon alumnus Phil Knight founded shoe giant Nike. Eugene's miles of running trails, through its unusually large park system, are the most extensive in the U.S. The city has dozens of running clubs. The climate is cool and temperate, good both for jogging and record-setting. Eugene is home to the University of Oregon's Hayward Field track, which hosts numerous collegiate and amateur track and field meets throughout the year, most notably the Prefontaine Classic. Hayward Field was host to the 2004 AAU Junior Olympic Games, the 1989 World Masters Athletics Championships, the track and field events of the 1998 World Masters Games, the 2006 Pacific-10 track and field championships, the 1971, 1975, 1986, 1993, 1999, 2001, 2009, and 2011 USA Track & Field Outdoor Championships and the 1972, 1976, 1980, 2008, 2012, and 2016 U.S. Olympic trials.

On April 16, 2015, it was announced by the IAAF that Eugene had been awarded the right to host the 2021 World Athletics Championships.[167] The city bid for the 2019 event but lost narrowly to Doha, Qatar.

Eugene is also home to the Eugene Emeralds, a short-season Class A minor-league baseball team. The "Ems" play their home games in PK Park, also the home of the University of Oregon baseball team.

The Nationwide Tour's golfing event Oregon Classic takes place at Shadow Hills Country Club, just north of Eugene. The event has been played every year since 1998, except in 2001 when it was slated to begin the day after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The top 20 players from the Nationwide Tour are promoted to the PGA Tour for the following year.[168]

The Eugene Jr. Generals, a Tier III Junior "A" ice hockey team belonging to the Northern Pacific Hockey League (NPHL) consisting of 8 teams throughout Oregon and Washington, plays at the Lane County Ice Center.

Lane United FC, a soccer club that participates in the Northwest Division of USL League Two, was founded in 2013 and plays its home games at Civic Park.

The following table lists some sports clubs in Eugene and their usual home venue:

Parks and recreation

Spencer Butte Park at the southern edge of town provides access to Spencer Butte, a dominant feature of Eugene's skyline. Hendricks Park, situated on a knoll to the east of downtown, is known for its rhododendron garden and nearby memorial to Steve Prefontaine, known as Pre's Rock, where the legendary University of Oregon runner was killed in an auto accident. Alton Baker Park, next to the Willamette River, contains Pre's Trail. Also next to the Willamette are Skinner Butte Park[169] and the Owen Memorial Rose Garden, which contains more than 4,500 roses of over 400 varieties,[170] as well as the 150-year-old Black Tartarian Cherry tree,[171] an Oregon Heritage Tree.[172]

The city of Eugene maintains an urban forest. The University of Oregon campus is an arboretum, with over 500 species of trees. The city operates and maintains scenic hiking trails that pass through and across the ridges of a cluster of hills in the southern portion of the city, on the fringe of residential neighborhoods. Some trails allow biking, and others are for hikers and runners only.

The nearest ski resort, Willamette Pass, is one hour from Eugene by car. On the way, along Oregon Route 58, are several reservoirs and lakes, the Oakridge mountain bike trails, hot springs, and waterfalls within Willamette National Forest. Eugene residents also frequent the Hoodoo and Mount Bachelor ski resorts. The Three Sisters Wilderness, the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, and Smith Rock are just a short drive away.

Government

In 1944, Eugene adopted a council–manager form of government, replacing the day-to-day management of city affairs by the part-time mayor and volunteer city council with a full-time professional city manager. The subsequent history of Eugene city government has largely been one of the dynamics—often contentious—between the city manager, the mayor and city council.

According to statute, all Eugene and Lane County elections are officially non-partisan, with a primary containing all candidates in May. If a candidate gets more than 50% of the vote in the primary, they win the election outright, otherwise the top two candidates face off in a November runoff. This allows candidates to win seats during the lower-turnout primary election.

The mayor of Eugene is Lucy Vinis, who has been in office since winning the popular vote in May 2016, and who was re-elected in May 2020. Recent mayors include Edwin Cone (1958–69), Les Anderson (1969–77) Gus Keller (1977–84), Brian Obie (1985–88), Jeff Miller (1989–92), Ruth Bascom (1993–96), Jim Torrey (1997–2004) and Kitty Piercy (2005-2017).

Eugene City Council

Mayor: Lucy Vinis

- Ward 1 – Emily Semple

- Ward 2 – Betty Taylor

- Ward 3 – Alan Zelenka

- Ward 4 – Jennifer Yeh

- Ward 5 – Mike Clark

- Ward 6 – Greg Evans

- Ward 7 – Claire Syrett

- Ward 8 – Chris Pryor[173]

Public safety

The Eugene Police Department is the city's law enforcement and public safety agency.[174] The Lane County Sheriff's Office also has its headquarters in Eugene.[175]

The University of Oregon is served by the University of Oregon Police Department,[176][177] and Eugene Police Department also has a police station in the West University District near campus. Lane Community College is served by the Lane Community College Public Safety Department.[178] The Oregon State Police have a presence in the rural areas and highways around the Eugene metro area.[179] The LTD downtown station, and the EmX lines are patrolled by LTD Transit Officers. Since 1989 the mental health crisis intervention non-governmental agency CAHOOTS has responded to Eugene's mental health 911 calls.[180][181]

Eugene used to have an ordinance which prohibited car horn usage for non-driving purposes. After several residents were cited for this offense during the anti-Gulf War demonstrations in January 1991, the city was taken to court and in 1992 the Oregon Court of Appeals overturned the ordinance, finding it unconstitutionally vague.[182] Eugene City Hall was abandoned in 2012 for reasons of structural integrity, energy efficiency, and obsolete size. Various offices of city government became tenants in eight other buildings.

Politics

As the biggest city by far in Lane County, Eugene's voters almost always single-handedly decide the partisan tilt and the margins. While Eugene has always been a counter-culture-heavy and liberal college town, the last two decades have seen that etched into stone as a reliable Democratic voting block due to Oregon's voters polarizing via an urban-Democratic/rural-Republican split.[183]

Lane County voted for Bernie Sanders over eventual 2016 nominee Hillary Clinton at an overall 60.6-38.1% margin with an even higher Sanders margin within Eugene city limits.[184]

Education

Eugene is home to the University of Oregon. Other institutions of higher learning include Northwest Christian University, Lane Community College, New Hope Christian College, Gutenberg College, and Pacific University's Eugene campus.

Schools

The Eugene School District includes four full-service high schools (Churchill, North Eugene, Sheldon, and South Eugene) and many alternative education programs, such as international schools and charter schools. Foreign language immersion programs in the district are available in Spanish, French, Chinese, and Japanese.

The Bethel School District serves children in the Bethel neighborhood on the northwest edge of Eugene. The district is home to the traditional Willamette High School and the alternative Kalapuya High School. There are 11 schools in this district.

Eugene also has several private schools, including the Eugene Waldorf School,[185] the Outdoor High School, Eugene Montessori, Far Horizon Montessori, Eugene Sudbury School,[186] Wellsprings Friends School,[187] Oak Hill School,[188] and The Little French School.[189]

Parochial schools in Eugene include Marist Catholic High School, O'Hara Catholic Elementary School, Eugene Christian School, and St. Paul Parish School.[190]

Libraries

The largest library in Oregon is the University of Oregon's Knight Library, with collections totaling more than 3 million volumes and over 100,000 audio and video items.[191] The Eugene Public Library[192] moved into a new, larger building downtown in 2002. The four-story library is an increase from 38,000 to 130,000 square feet (3,500 to 12,100 m2).[193] There are also two branches of the Eugene Public Library, the Sheldon Branch Library in the neighborhood of Cal Young/Sheldon, and the Bethel Branch Library, in the neighborhood of Bethel. Eugene also has the Lane County Law Library.

Media

Print

The largest newspaper serving the area is The Register-Guard, a daily newspaper with a circulation of about 70,000, published independently by the Baker family of Eugene until 2018, before being acquired by GateHouse Media.[194] Other newspapers serving the area include the Eugene Weekly, the Emerald, the student-run independent newspaper at the University of Oregon, now published on Mondays and Thursdays;The Torch, the student-run newspaper at Lane Community College, the Ignite, the newspaper at New Hope Christian College and The Beacon Bolt, the student-run newspaper at Bushnell University. Eugene Magazine, Lifestyle Quarterly, Eugene Living, and Sustainable Home and Garden magazines also serve the area. Adelante Latino is a Spanish language newspaper in Eugene that serves all of Lane County.

Television

Local television stations include KMTR (NBC), KVAL (CBS), KLSR-TV (Fox), KEVU-CD, KEZI (ABC), KEPB (PBS), and KTVC (independent).

Radio

The local NPR affiliates are KOPB, and KLCC. Radio station KRVM-AM is an affiliate of Jefferson Public Radio, based at Southern Oregon University. The Pacifica Radio affiliate is the University of Oregon student-run radio station, KWVA. Additionally, the community supports two other radio stations: KWAX (classical) and KRVM-FM (alternative).

AM Stations

- KOAC 550 Corvallis – NPR News/Talk (Oregon Public Broadcasting)

- KUGN 590 Eugene – NEWS/TALK (Cumulus)

- KXOR 660 Junction City – Spanish Religious (Zion Media)

- KKNX 840 Eugene – Classic Hits (Mielke Broadcasting)

- KORE 1050 Springfield – FOX Sports Radio

- KPNW 1120 Eugene – NEWS/TALK (Bicostal Media)

- KRVM 1280 Eugene – NPR News/Talk (Eugene School District) (JPR affiliate)

- KSCR 1320 Eugene – Soft AC (Cumulus)

- KNND 1400 Cottage Grove – Classic Country (Reiten Communications Inc)

- KEED 1450 Eugene – Classic Country (Mielke Broadcasting)

- KOPB 1600 Eugene – NPR News/Talk (Oregon Public Broadcasting)

FM Stations

- KWVA 88.1 Eugene – Freeform (University of Oregon)

- KPIJ 88.5 Junction City – Christian (Calvary Satellite Network) (Calvary Chapel)

- KQFE 88.9 Springfield – Christian (Family Radio)

- KLCC 89.7 Eugene – NPR News/Talk/Jazz (Lane Community College)

- KWAX 91.1 Eugene – Classical (University of Oregon)

- KRVM 91.9 Eugene – Adult Album Alternative (AAA) (Eugene School District)

- KKNU 93.3 Springfield – Country (McKenzie River Broadcasting)

- KMGE 94.5 Eugene – Adult Contemporary (McKenzie River Broadcasting)

- KUJZ 95.3 Creswell – Sports (Cumulus)

- KZEL 96.1 Eugene – Classic Rock (Cumulus)

- KEPW-LP 97.3 Eugene - PeaceWorks Community Radio (Eugene PeaceWorks)

- KEQB 97.7 Coburg - Regional Mexican (McKenzie River Broadcasting)

- KODZ 99.1 Eugene – Classic Hits (Bicoastal Media)

- KRKT 99.9 Albany – Country (Bicoastal Media)

- KMME 100.5 Cottage Grove – Catholic Program (Catholic Radio Northwest)

- KFLY 101.5 Corvallis - Country (Bicoastal Media)

- KEHK 102.3 Brownsville – Hot Adult Contemporary (Cumulus)

- KNRQ 103.7 Harrisburg – Alternative Rock (Cumulus)

- KDUK 104.7 Florence – Top 40 (CHR) (Bicoastal Media)

- KEUG 105.5 Veneta – Adult Hits (McKenzie River Broadcasting)

- KLOO 106.3 Corvallis – Classic Rock (Bicoastal Media)

- KLVU 107.1 Sweet Home – Contemporary Christian Music (K-LOVE) Educational Media Foundation

- KHPE 107.9 Albany – Contemporary Christian Music (Extra Mile Media)

Infrastructure

Bus

Lane Transit District (LTD), a public transportation agency formed in 1970, covers 240 square miles (620 km2) of Lane County, including Creswell, Cottage Grove, Junction City, Veneta, and Blue River. Operating more than 90 buses during peak hours, LTD carries riders on 3.7 million trips every year. LTD also operates a bus rapid transit line that runs between Eugene and Springfield—Emerald Express (EmX)—much of which runs in its own lane, with stations providing for off-board fare payment. LTD's main terminus in Eugene is at the Eugene Station. LTD also offers paratransit.

Greyhound Lines provides service between Los Angeles and Portland on the I-5 corridor.

Cycling

Cycling is popular in Eugene and many people commute via bicycle. Summertime events and festivals frequently have bike parking "corrals" that are often filled to capacity by three hundred or more bikes. Many people commute to work by bicycle every month of the year. Bike trails take commuting and recreational bikers along the Willamette River past a scenic rose garden, along Amazon Creek, through the downtown, and through the University of Oregon campus. Eugene is close to many popular mountain bike trails, and Disciples of Dirt is the local mountain bike club that organizes group rides and promotes trail stewardship.[195]

In 2009, the League of American Bicyclists cited Eugene as 1 of 10 "Gold-level" cities in the U.S. because of its "remarkable commitments to bicycling."[196][197][198] In 2010, Bicycling magazine named Eugene the 5th most bike-friendly city in America.[199][200] The U.S. Census Bureau's annual American Community Survey reported that Eugene had a bicycle commuting mode share of 7.3% in 2011, the fifth highest percentage nationwide among U.S. cities with 65,000 people or more, and 13 times higher than the national average of 0.56%.[201]

Rail

The 1908 Amtrak depot downtown was restored in 2004; it is the southern terminus for two daily runs of the Amtrak Cascades, and a stop along the route in each direction for the daily Coast Starlight.

Air travel

Air travel is served by the Eugene Airport, also known as Mahlon Sweet Field, which is the fifth largest airport in the Northwest and second largest airport in Oregon. The Eugene Metro area also has numerous private airports.[202] The Eugene Metro area also has several heliports, such as the Sacred Heart Medical Center Heliport and Mahlon Sweet Field Heliport, and many single helipads.[203]

Highways

Highways traveling within and through Eugene include:

- Interstate 5: Interstate 5 forms much of the eastern city limit, acting as an effective, though unofficial boundary between Eugene and Springfield. To the north, I-5 leads to the Willamette Valley and Portland. To the south, I-5 leads to Roseburg, Medford, and the southwestern portion of the state. In full, Interstate 5 continues north to the Canada–US border at Blaine, Washington and Vancouver, British Columbia and extends south to the Mexico–US border at Tijuana and San Diego.

- Officer Chris Kilcullen Memorial Highway: Oregon Route 126 is routed along the Eugene-Springfield Highway, a limited-access freeway. The Eugene portion of this highway begins at an interchange with Interstate 5 and ends two miles (3 km) west at a freeway terminus. This portion of Oregon Route 126 is also signed Interstate 105, a spur route of Interstate 5. Oregon Route 126 continues west, a portion shared with Oregon Route 99, and continues west to Florence. Eastward, Oregon Route 126 crosses the Cascades and leads to central and eastern Oregon.

- Randy Papé Beltline: Beltline is a limited-access freeway which runs along the northern and western edges of incorporated Eugene.

- Delta Highway: The Delta Highway forms a connector of less than 2 miles (3.2 km) between Interstate 105 and Beltline Highway.

- Oregon Route 99: Oregon Route 99 forks off Interstate 5 south of Eugene, and forms a major surface artery in Eugene. It continues north into the Willamette valley, parallel to I-5. It is sometimes called the "scenic route" since it has a great view of the Coast Range and also stretches through many scenic farmlands of the Willamette Valley.

Utilities

Eugene is the home of Oregon's largest publicly owned water and power utility, the Eugene Water & Electric Board (EWEB). EWEB got its start in the first decade of the 20th century, after an epidemic of typhoid found in the groundwater supply.[204] The City of Eugene condemned Eugene's private water utility and began treating river water (first the Willamette; later the McKenzie) for domestic use. EWEB got into the electric business when power was needed for the water pumps. Excess electricity generated by the EWEB's hydropower plants was used for street lighting.

Natural gas service is provided by NW Natural.

Wastewater treatment services are provided by the Metropolitan Wastewater Management Commission, a partnership between the Cities of Eugene and Springfield and Lane County.

Healthcare

Three hospitals serve the Eugene-Springfield area. Sacred Heart Medical Center University District is the only one within Eugene city limits. McKenzie-Willamette Medical Center and Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend are in Springfield. Oregon Medical Group, a primary care based multi-specialty group, operates several clinics in Eugene,[205] as does PeaceHealth Medical Group.[206] White Bird Clinic provides a broad range of health and human services, including low-cost clinics.[207][208] The Volunteers in Medicine & Occupy Medical clinics provide free medical and mental care to low-income adults without health insurance.[209][210]

Eugene is one of the few municipalities in the US that does not fluoridate its water supply.[211]

Notable people

Sister cities

Eugene has four sister cities:[212]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Shoemaker, Alex. "Eugene Marathon Moving to Late July for 2014". Eugene Daily News. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

...as a native Eugenian...

- Nguyen, Nha (July 17, 2013). "ODOT: New Ramp Meters to Ease Traffic". KEZI. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

Fellow Eugenian...

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Oregon's 2010 Census Population Totals". 2010.census.gov. February 23, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- Hill, Christian. "State, federal estimates agree: Eugene's population tops 170,000". The Register-Guard. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- "University of Oregon". uoregon.edu. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- "Northwest Christian University - Private University in Eugene, Oregon". Northwest Christian University. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- "Lane Community College". www.lanecc.edu. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Nico, Lisa (December 16, 2014). "Springfield's 'Simpsons' tour highlights similarities to local spots". KATU. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Eugene dials back its slogan". OregonLive.com. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Caple, Jim (July 4, 2008). "Why did we have to wait so long for the trials to return to Pre Country?". ESPN. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- "History & Heritage". Nike. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010.

- "Eugene to Host 2021 Track World Championships". Runner's World. April 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Lewis, Ph.D, David G. (November 8, 2016). "Kalapuyans: Seasonal Lifeways, Tek, Anthropocene". NDN History Research: Critical and Indigenous Anthropology. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Berg, Laura (2007). The First Oregonians (2nd ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Council for the Humanities. pp. 307–315. ISBN 9781880377024.

- Lewis, Ph.D., David G. (May 23, 2016). "Chafin Band Reservation and Village 1855". NDN History Research: Critical and Indigenous Anthropology. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "Chifin Native Youth Center". Springfield Public Schools. Springfield, Oregon, Public Schools. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Lewis, Ph.D., David G. (December 8, 2014). "Chifin Kalapuya Village". NDN History Research: Critical and Indigenous Anthropology. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Mackey, Ph.D., Harold (2004). The Kalapuyans: A Sourcebook on the Indians of the Willamette Valley. Salem, Oregon, and Grand Ronde, Oregon: Mission Mill Museum Association, Inc.and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780975348406.

- Jette, Melinda Marie (2015). At the Hearth of Crossed Races: A French Indian Community in Nineteenth-Century Oregon, 1812-1859. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 9780870715976.

- Jette, Melinda Marie (2015). At the Hearth of Crossed Races: A French Indian Community in Nineteenth Century Oregon, 1812-1859. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. pp. 12–61, p. 147. ISBN 9780870715976.

- Jette, Melinda Marie (2015). At the Hearth of Crossed Races: A French Indian Community in Nineteenth Century Oregon, 1812-1859. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. pp. 61–69. ISBN 9780870715976.

- Jette, Melinda Marie (2015). At the Hearth of Crossed Races: A French Indian Community in Nineteenth Century Oregon, 1812-1859. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. pp. 65–67. ISBN 9780870715976.

- Jette, Melinda Marie (2015). At the Hearth of Crossed Races: A French Indian Community in Nineteenth Century Oregon, 1812-1859. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780870715976.

- Ruby, Robert, MD, John A. Brown, Cary C. Collins (2010). A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780806140247.

- Berg, Laura (2007). The First Oregonians, Second Edition. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Council for the Humanities. p. 127. ISBN 9781880377024.

- Berg, Laura (2007). The First Oregonians, Second Edition. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Council for the Humanities. p. 126. ISBN 9781880377024.

- Skinner, Eugene (2009). "Photo and text - Eugene Skinner". Lane County Historical Society. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Zenk, Henry (2008). "Notes on Native American Place-names of the Willamette Valley Region". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 109: 6–33.

- "Eugene, Oregon, United States". www.britannica.com. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Terry, John (September 4, 2010). "Founder's wife suggests unique name for city of Eugene". The Oregonian. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Morrison, Perry D. (December 1955). "Columbia College 1856-60". Oregon Historical Quarterly. Oregon Historical Society. 56 (4): 326–351. JSTOR 20612220.

- College Hill Neighborhood and History. Archived August 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine College Hill Cultural Resource Survey (1988).

- Richard, Terry; O'Neal, Jennifer (November 10, 2012). "University of Oregon history in a nutshell, from campus historian". oregonlive. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- Deady Hall: Architecture of the University of Oregon. University of Oregon Libraries. Retrieved on January 21, 2008.

- "How 'Niketown' became the centre of the latest athletics controversy". The Independent. December 15, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Eugene Government Historical Perspective". July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "OREGON CITY IS CRADLE TO LATEST GENERATION OF ANARCHIST PROTESTERS". August 12, 2000. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Last Occupy Eugene camper leaves city park". KVAL-13. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Hutchinson, Bill. "Police declare riots as protests turn violent in cities nationwide; 1 demonstrator dead in Austin". ABC News. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- "Arson at Eugene Armory". September 30, 1968. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Oregon Saboteurs Dynamite Church, Bank, Other Buildings". May 21, 1969. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Student Protests on the UO Campus: Demonstrations of the Late 1960s". January 20, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Historic Johnson Hall past witness to protests, bombing attempts". November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Tiny Neighborhood Fights For Its Life". February 3, 1978. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Hundreds Arrested in Anti-War Demonstrations". January 15, 1991. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Tens of thousands rally against war". January 16, 1991. Retrieved July 18, 2020.