Timbuktu (2014 film)

Timbuktu is a 2014 Mauritanian-French drama film directed and co-written by Abderrahmane Sissako. It was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or in the main competition section at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival.[4][5][6] At Cannes, it won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury and the François Chalais Prize.[7][8] It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 87th Academy Awards,[9][10] and has been nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language at the 69th British Academy Film Awards. It won Best Film at the 11th Africa Movie Academy Awards.[11] The film was named the twelfth "Best Film of the 21st Century So Far" in 2017 by The New York Times.[12]

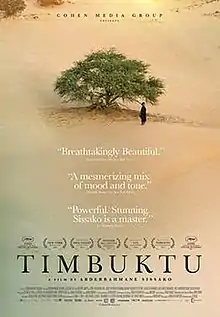

| Timbuktu | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Abderrahmane Sissako |

| Produced by | Sylvie Pialat Étienne Comar |

| Written by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Amine Bouhafa |

| Cinematography | Sofian El Fani |

| Edited by | Nadia Ben Rachid |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Cohen Media Group |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[1] |

| Country |

|

| Language |

|

| Box office | $7.2 million[3] |

The film looks at the brief occupation of Timbuktu, Mali by Ansar Dine. Parts of the film were influenced by a 2012 public stoning of an unmarried couple in Aguelhok.[13] It was shot in Oualata, a town in south-east Mauritania.[14]

Plot

The film explores the denizens of the city of Timbuktu, Mali, in West Africa, who are living under strict sharia law around the year 2012. The city is under the occupation of extremist Islamists bearing a jihadist black flag. The dignified Kidane is a cattle herder who lives outside of the city. One day, one of his cows accidentally damages the net of a fisherman. The enraged fisherman kills the cow. Having armed himself with a pistol, Kidane confronts the fisherman and accidentally shoots him dead. The jihadists arrest Kidane and, per sharia law, offer to spare his life if the victim's family forgive him and he pays diya (blood money) of 40 cattle. Kidane's daughter corrals the cattle but no forgiveness is forthcoming so he is sentenced to death. His wife shows up at his execution and as they run to each other the executioners gun them down. Kidane's daughter flees.

Themes

Throughout the film, there are subsidiary scenes showing the reaction of the population to the jihadists' rule, which are portrayed as absurd. A female fishmonger must wear gloves even when selling fish. Music is banned; a woman is sentenced to 40 lashes for singing, and 40 lashes for being in the same room as a man not of her family. A couple are buried up to their necks in sand and stoned to death for adultery. Young men play football with an imaginary ball as sports are banned. A local imam tries to curb the jihadists' excesses with sermons. A young woman is forced into marriage to a young jihadi with the blessing of the occupiers who cherrypick sharia in justification.

The film also acknowledges the failure of the occupiers to live up to their own rules. One of their leaders, Abdelkerim, is seen smoking a cigarette. At another point, he and a group of jihadists from France discuss their favorite football players.

Characters speak in Tamasheq, Bambara, Arabic, French, and on a few occasions English. The mobile phone is an important means of communication.

Cast

- Ibrahim Ahmed dit Pino as Kidane

- Toulou Kiki as Satima

- Layla Walet Mohamed as Toya

- Mehdi Ag Mohamed as Issan

- Kettly Noel as Zabou

- Abel Jafri as Abdelkerim

- Hichem Yacoubi

- Pino Desperado

- Fatoumata Diawara as La Chanteuse

- Omar Haidara as Amadou

- Damien Ndjie as Abu Jaafar

Production

This fifth film of Sissako was inspired by the true story of a young, unmarried couple who were stoned by Islamists in the northern region of Mali that was known as Aguel'hoc. During the summer of 2012, the couple was taken to the center of their village, placed in two holes that had been dug in the ground, and stoned to death in front of hundreds of witnesses.[15][16][17][18]

According to the journalist Nicolas Beau, Sissako wanted to shoot a film on slavery in Mauritania, which was not acceptable to the country's president Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz. Sissako then agreed to make a film on the jihadists, with the support of the Mauritanian government which supplied both financial and human resources.[19]

Shortly before the opening of the film in Cannes in 2014, Sissako set off again to Timbuktu with a small team to add some scenes at the last minute.

Reception

Critical reception

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 98% approval rating and an average rating of 8.80/10 based on 122 reviews. The website's critical consensus reads, "Gracefully assembled and ultimately disquieting, Timbuktu is a timely film with a powerful message."[20] It also received a score of 92 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 31 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[21] According to both Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes, Timbuktu is the best reviewed foreign-language film of 2015.[22][23]

Jay Weissberg of Variety writes, "In the hands of a master, indignation and tragedy can be rendered with clarity yet subtlety, setting hysteria aside for deeper, more richly shaded tones. Abderrahmane Sissako is just such a master."[24] In a review for The Daily Telegraph, Tim Robey suggested it was a "wrenching tragic fable, Aesop-like in its moral clarity." He went on to say it was "full of life, irony, poetry and bitter unfairness."[25]

In the Financial Times, Nigel Andrews called it "skilful, sardonic, honourably humane."[26] Reviewing it for The Guardian, Jonathan Romney called it, "witty, beautiful and even, sobering though it is, highly entertaining" as well as "mischievous and imaginative." He concluded that it was "a formidable statement of resistance."[27]

Sight & Sound's Nick Pinkerton says "The fact remains that there are few filmmakers alive today wearing a mantle of moral authority comparable to that which Sissako has taken upon himself, and if his film has been met with an extraordinary amount of acclaim, it is because he manages to wear this mantle lightly, and has not confused drubbing an audience with messages with profundity. I can’t imagine the film having been made any other way, by anyone else – and this is one measure of greatness."[28]

Accolades

The film won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Foreign Language Film[29] and the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[30] In 2016, it was voted the 36th best film of the 21st century as picked by 177 film critics from around the world.[31]

See also

- List of submissions to the 87th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Mauritanian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- "Timbuktu (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Timbuktu". TIFF Festival '14. Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Timbuktu (2015)". JP's Box-Office. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "2014 Official Selection". Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Obenson, Tambay A. (17 April 2014). "Films By Abderrahmane Sissako & Philippe Lacôte Are Cannes 2014 Official Selections". IndieWire. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Dowd, Vincent (20 May 2014). "Timbuktu film at Cannes mixes tragedy, charm and humour". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Barraclough, Leo (23 May 2014). "'Winter Sleep', 'Jauja', 'Love at First Fight' Take Cannes Fipresci Prizes". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ""Timbuktu", prix du Jury oecuménique et prix François-Chalais". Le Parisien. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Obenson, Tambay A. (8 September 2014). "Abderrahmane Sissako's 'Timbuktu' Is Mauritania's Best Foreign Language 2015 Oscar Competition Entry". IndieWire. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Jacobs, Matthew (15 January 2015). "Oscar Nominations 2015: See The Full List". The Huffington Post. Oath. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Sanusi, Hassan. "AMAA 2015: Full list of WINNERS". Nigerian Entertainment Today. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Dargis, Manohla; Scott, A.O. (9 June 2017). "The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century...So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Timbuktu". New Zealand International Film Festival. New Zealand Film Festival Trust. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Mohamed, Al-Sheikh (27 September 2014). "Mauritanians delighted with Timbuktu Oscar nomination". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Nord-Mali : des islamistes tuent un couple non marié par lapidation". Le Monde. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Mali - L'insoutenable lapidation d'un couple non-marié". Slate Afrique. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Adam Nossiter (30 July 2012). "Islamists in North Mali Stone Couple to Death". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Mali unwed couple stoned to death by Islamists". BBC. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Abderrahmane Sissako, une imposture mauritanienne, Mondafrique, 20 février 2015. Dead link

- "Timbuktu (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "Timbuktu Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Dietz, Jason (5 January 2016). "The Best Movies of 2015". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- McGree, Jester (16 December 2015). "Best Foreign Language Movie 2015". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Weissberg, Jay (14 May 2014). "Film Review: 'Timbuktu'". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Robey, Tim (28 May 2015). "Timbuktu review: 'a brutal Sharia law fable'". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Andrews, Nigel (28 May 2015). "Timbuktu — film review". Financial Times. The Nikkei. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Romney, Jonathan (31 May 2015). "Timbuktu review – defiant song of a nation in peril". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Pinkerton, Nick (28 May 2015). "Film of the week: Timbuktu". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "2015 Awards". New York Film Critics Circle Awards. New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- nsfc2017. "Awards for 2015 films". National Society of Film Critics. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Culture - The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

External links

- Timbuktu at IMDb

- Timbuktu at Box Office Mojo

- Timbuktu at Rotten Tomatoes

- Timbuktu at Metacritic