Rome, Open City

Open City[2] or Rome, Open City (Italian: Roma città aperta) is a 1945 Italian neorealist drama film directed by Roberto Rossellini. The picture features Aldo Fabrizi, Anna Magnani and Marcello Pagliero, and is set in Rome during the Nazi occupation in 1944. The title refers to Rome being declared an open city after 14 August 1943. The film won several awards at various film festivals, including the most prestigious Cannes Grand Prix and was nominated for the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar at the 19th Academy Awards.

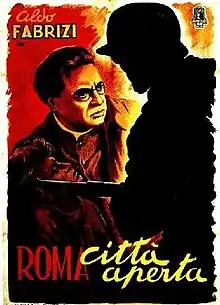

| Rome, Open City | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roberto Rossellini |

| Produced by | Giuseppe Amato Ferruccio De Martino Roberto Rossellini Rod E. Geiger |

| Screenplay by | Sergio Amidei Federico Fellini |

| Story by | Sergio Amidei |

| Based on | Stories of Yesteryear by Sergio Amidei Alberto Consiglio |

| Starring | Aldo Fabrizi Anna Magnani Marcello Pagliero |

| Music by | Renzo Rossellini |

| Cinematography | Ubaldo Arata |

| Edited by | Eraldo Da Roma |

| Distributed by | Minerva Film (Italy) Joseph Burstyn & Arthur Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian German |

| Box office | $1 million[1] |

Plot

In occupied Rome in 1944, German SS troops are trying to arrest the engineer Giorgio Manfredi, a communist and a leader of the Resistance against the German Nazis and Italian Fascists, who is staying in a rooming house. The landlady warns him in time of the Germans' arrival, so that he can elude them by jumping across the rooftops. He goes to the home of Francesco, another Resistance fighter. There he encounters Pina who lives in the next apartment. Pina, Francesco's fiancée, is visibly pregnant. She first suspects Giorgio of being a cop and gives him a rough time, but when he makes it clear he is not, she welcomes him into Francesco's apartment to wait for him. With Pina's help (she is also part of the Resistance), Giorgio contacts Don Pietro Pellegrini, a Catholic priest who is helping the Resistance, and asks him to transfer messages and money to a group of Resistance fighters outside the city as Giorgio is now known to the Gestapo and cannot do it himself.

Don Pietro is scheduled to officiate at Pina's and Francesco's wedding the next day. Francesco is not very religious, but rather would be married by a patriot priest than a fascist official; Pina, on the other hand, is devout, but wrestling with why God would allow such terrible things to happen to people. Her son, Marcello, is a somewhat reluctant altar boy. He and his friends have a small role in the Resistance planting bombs. Pina's sister Laura stays with her, but is not involved in the Resistance; in fact, she works in a cabaret serving the Nazis and Fascists. She is also an old friend of Marina, a girlfriend of Giorgio who has been looking for him, but with whom he is splitting up. Marina also works in the cabaret and as an occasional prostitute.

The local SS commander in the city, helped by the Italian police commissioner, suspects that Giorgio is at Francesco's apartment. They conduct a huge raid, pulling out all the people and arresting dozens of men. Giorgio gets away, but Francesco is thrown in a truck with other arrestees. Seeing him being taken away, Pina breaks through a cordon of police and runs towards him, but is shot dead. The priest, who was in the building to hide weapons, under the guise of praying for a dying man, holds her in his arms and prays for her soul. The truck drives away in a convoy with military vehicles, but outside of town it is attacked by Resistance fighters, and many of the captives escape. Francesco makes it back into Rome and reconnects with Giorgio. Together they go to the priest, who has offered to hide them in a monastery.

Marina betrays her former lover in exchange for drugs and a fur coat. Using information given by Marina, the Gestapo and Italian police capture Giorgio and the priest, along with an Austrian defector, on their way to the monastery. Francesco is saying goodbye to Marcello, and sees them get picked up and gets away. The defector, fearing torture, hangs himself in his cell. The Gestapo try to get Giorgio to betray his comrades, but it is in vain. He does not respond to sweet talk, so they torture him intensely; they want to break him before word gets out that he was arrested, so they can take the Resistance by surprise with the information they hope to extract from Giorgio.

They also try to use Don Pietro's influence on Giorgio to convince him to betray his cause, saying that he is an atheist and communist who is the enemy, but Don Pietro responds that anyone who strives to live a righteous life is on the path of God whether they believe in Him or not. They then force Don Pietro to watch Giorgio's torture. When Giorgio dies without revealing anything, Don Pietro blesses his body and commends him to God's mercy (last rites and sacraments cannot be given to someone who has died). Giorgio's refusal to yield shakes the confidence of the Germans, including the commander, who had boasted to the priest and the collaborating woman that they were the "master race", and no one from a "slave race" could withstand their torture.

Marina and a German officer stumble into the scene while intoxicated; she faints when she sees that the Germans have tortured Giorgio to death rather than treat him well as she had been led to expect. Realizing that she was responsible for this, she passes out. The Gestapo chief and the collaborator decide that she is now useless to them and arrest her, taking away the fur coat they had given her as a bribe.

Don Pietro still refuses to crack, so he is taken to be executed early the next morning before his parish can learn of his arrest and respond with a protest. However, the parish altar boys/Resistance fighters show up to where Don Pietro is being executed, and they begin whistling a tune which Don Pietro recognizes. The Italian firing squad is lined up to execute Don Pietro, but some deliberately miss him. The German officer in charge of the execution squad walks over to Don Pietro as soon as he realizes that the Italians will not kill a priest, and executes Don Pietro himself.

At this, the altar boys and Resistance fighters grow silent, bow their heads in grief, and slowly walk away. As the kids make way back into the city, a final shot of the city of Rome and St. Peter's Basilica can be seen clearly in the background.

Cast

- Aldo Fabrizi – Don Pietro Pellegrini

- Anna Magnani – Pina

- Marcello Pagliero – Giorgio Manfredi, alias Luigi Ferraris

- Vito Annicchiarico – Marcello, Pina's son

- Nando Bruno – Agostino, the Sexton

- Harry Feist – Major Bergmann

- Giovanna Galletti – Ingrid

- Francesco Grandjacquet – Francesco

- Eduardo Passarelli – neighborhood Police Sergeant

- Maria Michi – Marina Mari

- Carla Rovere – Lauretta, Pina's sister

- Carlo Sindici – Police Commissioner

- Joop van Hulzen – Captain Hartmann

- Ákos Tolnay – Austrian deserter

- Alberto Tavazzi – Priest

Production

By the end of World War II, Rossellini had abandoned the film Desiderio because conditions made it impossible to complete (it later was finished by Marcello Pagliero in 1946 and disowned by Rossellini). By 1944, there was virtually no film industry in Italy and no money to fund films. Rossellini had met and befriended a wealthy, elderly lady in Rome who wanted to finance a documentary on Don Pieto Morosini, a Catholic priest who had been shot by the Germans for helping the partisan movement in Italy. Rossellini wanted actor Aldo Fabrizi to play the priest in reenactments and contacted his friend Federico Fellini to help get in touch with Fabrizi.

By then, the lady had agreed to finance an additional documentary about Roman children who had fought against the German occupiers. Fellini and screenwriter Sergio Amidei suggested to Rossellini that, instead of two short documentaries, he should make one feature film that combined the two ideas, and in August 1944, just two months after the Allies had forced the Nazis to evacuate Rome, Rossellini, Fellini, and Amidei began working on the script for the film.

The devastation that was the result of the war surrounded them as they wrote the script. They titled it Roma, città aperta and declared publicly that it would be a history of the Roman people under Nazi occupation. Shooting for the film began in January 1945. The funding from the elderly Roman lady was never enough, and the film was crudely shot due to circumstances and not for stylistic reasons. The facilities at Cinecittà Studios were also unusable at that time due to unreliable electricity supply and poor quality film stock.

It is necessary to name Aldo Venturini, a key figure in the history of the film's production: Venturini was not a film man, he was a wool merchant who in the immediate post-war Roman period had strong financial resources and was immediately involved in the financing of the film by of the manufacturing company, Cis Nettunio. Then, after a few days of shooting, the film had stopped due to lack of liquidity, it was Rossellini who convinced the merchant, in April 1945, to complete the film as a producer, making him understand that that was the only way to recover. the money advanced. At that moment his intervention, at high financial risk, was aimed at continuing the work in an attempt to save his investment, as a real film producer would do.[3]

New Yorker Rod E. Geiger, a soldier in the Signal Corps, who eventually became instrumental in the movie's global success, met Rosselini at a point when they were out of film. Geiger had access to the film units at the Signal Corps that regularly threw away short-ends and complete rolls of film that might be fogged, scratched, or otherwise deemed unfit for use, and was able to obtain and deliver enough discarded stock to complete the picture.[4]

In order to authentically portray the hardships and poverty of Roman people under the occupation, Rossellini hired mostly non-professional actors for the film, with a few exceptions of established stars including Fabrizi and Anna Magnani. On the making of the film, Rossellini stated that the "situation of the moment guided by my own and the actors' moods and perspectives" dictated what they shot, and he relied more on improvisation than on a script. He also stated that the film was "a film about fear, the fear felt by all of us but by me in particular. I too had to go into hiding. I too was on the run. I had friends who were captured and killed."[5] Rossellini relied on traditional devices of melodrama, such as identification of the film's central characters and a clear distinction between good and evil characters. Four interior sets were constructed for the more important locations of the film.

It was believed that the actual film stock was put together out of many different disparate bits, giving the film its documentary or newsreel style. But, when the Cineteca Nazionale restored the print in 1995, "the original negative consisted of just three different types of film: Ferrania C6 for all the outdoor scenes and the more sensitive Agfa Super Pan and Agfa Ultra Rapid for the interiors." The previously unexplained changes in image brightness and consistency are now blamed on poor processing (variable development times, insufficient agitation in the developing bath and insufficient fixing).[6]

It was one of the early Italian films of the war to depict the struggle against the Germans, unlike the films made in the early years of the war (when Italy was Germany's ally under Mussolini) that depicted the British, Americans, Greeks, Russians and other allied countries, as well as Ethiopians, communists, and partisans as the antagonists. After the Allied Invasion of Italy in 1943, Italian morale crumbled, and they agreed to a separate peace with the allies, causing their former German allies to occupy large parts of Italy, intern Italian soldiers, deport Italian Jews to concentration camps, and treat many of its citizens with disdain for what they saw as a cowardly betrayal by one of their major allies.

Critical response

Rome, Open City received a mediocre reception from Italian audiences when it was first released when Italian people were said to want escapism after the war. However, it became more popular as the film's reputation grew in other countries.[7] The film brought international attention to Italian cinema and is considered a quintessential example of neorealism in film, so much so that together with Paisà and Germania anno zero it is called Rossellini's "Neorealist Trilogy". Robert Burgoyne called it "the perfect exemplar of this mode of cinematic creation [neorealism] whose established critical definition was given by André Bazin".[8] Rossellini himself traced what was called neorealism back to one of his earlier films The White Ship, which he claimed had the same style. Some Italian critics also maintained that neorealism was simply a continuation of earlier Italian films from the 1930s, such as those directed by filmmakers Francesco De Robertis and Alessandro Blasetti.[9] More recent scholarship points out that this film is actually less neo-realist and rather melodramatic.[10] Critics debate whether the pending marriage of the Catholic Pina and the communist Francesco really "acknowledges the working partnership of communists and Catholics in the actual historical resistance".[11]

Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times, gave the film a highly positive review, and wrote "Yet the total effect of the picture is a sense of real experience, achieved as much by the performance as by the writing and direction. The outstanding performance is that of Aldo Fabrizi as the priest, who embraces with dignity and humanity a most demanding part. Marcello Pagliero is excellent too, as the resistance leader, and Anna Magnani brings humility and sincerity to the role of the woman who is killed. The remaining cast is unqualifiedly fine, with the exception of Harry Feist in the role of the German commander. His elegant arrogance is a bit too vicious – but that may be easily understood."[12] Film critic William Wolf especially praised the scene where Pina is shot, stating that "few scenes in cinema have the force of that in which Magnani, arms outstretched, races towards the camera to her death."[13]

Pope Francis has said that the film is among his favorites.[14]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rare approval rating of 100% based on 42 reviews, with an average rating of 9.08/10. The site's critics' consensus reads: "Open City fills in the familiar contours of its storyline with three-dimensional characters and a narrative depth that add up to a towering – and still powerfully resonant – cinematic achievement."[15]

Distribution

The film opened in Italy on 27 September 1945, with the war damage to Rome not yet repaired. The United States premiere followed on 25 February 1946 in New York. The American release was censored, resulting in a cut of about 15 minutes. The story of the film's journey from Italy to the United States is recounted in Federico Fellini's autobiographical essay "Sweet Beginnings". Rod E. Geiger, a U.S. Army private stationed in Rome, met Rossellini and Fellini after catching them tapping into the power supply used to illuminate the G.I. dancehall.[16] In the book The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini, author Tag Gallagher credits Geiger at age 29 as the "man who more than any single individual was to make him and the new Italian cinema famous around the world".[17] Before the war, Geiger had worked for an American distributor and exhibitor of foreign films which helped facilitate the film's release in the United States. In gratitude, Rossellini gave Geiger a co-producer credit.[4][16]

However, According to Fellini's essay Geiger was "a 'half-drunk' soldier who stumbled (literally as well as figuratively) onto the set of Open City. [He] misrepresented himself as an American producer when actually he 'was a nobody and didn't have a dime.'"[18] Fellini's account of Geiger's involvement in the film was the subject of an unsuccessful defamation lawsuit brought by Geiger against Fellini.[18]

The film was banned in several countries. West Germany banned it from 1951 to 1960. In Argentina, it was inexplicably withdrawn in 1947 following an anonymous government order.[19]

Awards

Wins

- Cannes Film Festival: Grand Prize of the Festival; Roberto Rossellini; 1946.

- Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists (Sindacato Nazionale dei Giornalisti Cinematografici Italiani): Silver Ribbon (Nastro d'Argento); Best Film; Best Supporting Actress, Anna Magnani; 1946.

- National Board of Review: NBR Award Best Actress; Anna Magnani; Best Foreign Film, Italy; 1946.

- New York Film Critics Circle Awards: NYFCC Award Best Foreign Language Film, Italy; 1946.

See also

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator website

References

- Schallert, Edwin (Mar 11, 1951). "Influx of British Stars Continuing". Los Angeles Times. p. D3.

- "The 19th Academy Awards – 1947".

- 2

- Dmytrk, Edward. "Odd Man Out: A Memoir of the Hollywood Ten." SIU Press, 1996. p. 97

- Wakeman, John. World Film Directors, Volume 2. The H.W. Wilson Company. 1987. p. 961.

- Forgacs, David. Roma città aperta. London: British Film Institute, 2000.

- Wakeman. pp. 961–962.

- Burgoyne, Robert. "The Imaginary And The Neo-Real", Enclitic, 3: 1 (Spring, 1979) Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

- Wakeman. p. 962.

- Hillman, Roger. "The Penumbra of Neorealism", Forum for Modern Language Studies, 38: 2 (2002): 221–223.

- Shiel, Mark. Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City. New York: Wallflower Press (2006): 51.

- Crowther, Bosley. The New York Times, film review, "How Italy Resisted", 26 February 1946. Last accessed: December 20, 2007.

- Wakeman. p. 961.

- "A Big Heart Open to God: An interview with Pope Francis". 30 September 2013.

- "Open City (1946)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- Gottlieb, Sidney. "Roberto Rossellini's Rome Open City." Cambridge University Press, 2004. pp. 60, 67.

- Gallagher, Tag. The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini. Da Capo Press, 1998. p. 159

- "Rod Geiger, Plaintiff, Appellant, v. Dell Publishing Company, Inc. et al., Defendants, Appellees, 719 F.2d 515 (1st Cir. 1983)".

- Warren, Virginia Lee. The New York Times, "Delayed Censorship", 7 December 1947.

Further reading

- David Forgacs. Roma città aperta. London: British Film Institute, 2000.

- Stefano Roncoroni, La storia di Roma città aperta, Bologna-Recco, Cineteca di Bologna-Le Mani, 2006, ISBN 88-8012-324-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roma, città aperta. |

- Rome, Open City at IMDb

- Rome, Open City at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rome Open City: A Star Is Born an essay by Irene Bignardi at the Criterion Collection