Title (publishing)

The title of a book, or any other published text or work of art, is a name for the work which is usually chosen by the author. A title can be used to identify the work, to place it in context, to convey a minimal summary of its contents, and to pique the reader's curiosity.

Some works supplement the title with a subtitle. Texts without separate titles may be referred to by their incipit, especially those produced before the practice of titling became popular. During development, a work may be referred to by a temporary working title. A piece of legislation may have both a short title and a long title. In library cataloging, a uniform title is assigned to a work whose title is ambiguous.

In book design, the title is typically shown on the spine, the front cover, and the title page.

In the music industry album titles are often chosen through an involved process including record executives.[1]

History

The first books, such as the Five Books of Moses, in Hebrew Torah, did not have titles. They were referred to by their first word: Be-reshit, "In the beginning" (Genesis), Va-yikra, "And He [God] called" (Leviticus). The concept of a title is a step in the development of the modern book.[2]

In Ancient Greek Literature, books have one-word titles that are not the initial words: new words, but following grammatical principles. The Iliad is the story of Ilion (Troy), the Trojan War; the Odysseia (Odyssey) that of Odysseus (Ulysses). The first history book in the modern sense, Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, had no more title than Historiai (Histories or Stories).

When books take the form of a scroll or roll, as in the case of the Torah or the Five Megillot, it is impractical to single out an initial page. The first page, rolled up, would not be fully visible unless unrolled. For that reason, scrolls are marked with external identifying decorations.

A book with pages is not a scroll, but a codex, a stack of pages bound together through binding on one edge. Codices (plural of "codex") are much more recent than scrolls, and replaced them because codices are easier to use. The title "page" is a consequence of a bound book having pages. Until books had covers (another development in the history of the book), the top page was highly visible. To make the content of the book easy to ascertain, there came the custom of printing on the top page a title, a few words in larger letters than the body, and thus readable from a greater distance.

As the book evolved, most books became the product of an author. Early books, like those of the Old Testament, did not have authors. Gradually the concept took hold—Homer is a complicated case—but authorship of books, all of which were or were believed to be non-fiction, was not the same as, since the Western Renaissance, writing a novel. The concept of intellectual property did not exist; copying another person's work was once praiseworthy. The invention of printing changed the economics of the book, making it possible for the owner of a manuscript to make money selling printed copies. The concept of authorship became much more important. The name of the author would also go on the title page.

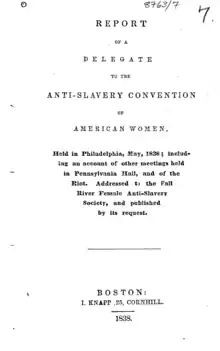

Gradually more and more information was added to the title page: the location printed, the printer, at later dates the publisher, and the date. Sometimes a book's title continued at length, becoming an advertisement for the book which a possible purchaser would see in a bookshop (see example)?

Typographical conventions

Most English-language style guides, including the Chicago Manual of Style, the Modern Language Association Style Guide,[3] and APA style[4] recommend that the titles of longer or complete works such as books, movies, plays, albums, and periodicals be written in italics, like: the New York Times is a major American newspaper. These guides recommend that the titles of shorter or subsidiary works, such as articles, chapters, and poems, be placed written within quotation marks, like: "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" is a poem by Robert Frost. The AP Stylebook recommends that book titles be written in quotation marks. Underlining is used where italics are not possible, such as on a typewriter or in handwriting.

Titles may also be written in title case, with most or all words capitalized. This is true both when the title is written in or on the work in question, and when mentioned in other writing. The original author or publisher may deviate from this for stylistic purposes, and other publications might or might not replicate the original capitalization when mentioning the work. Quotes, italics, and underlines are generally not used in the title on the work itself.[5]

See also

References

- Billboard - 20 Oct 1958 - Page 5 "First, it apparently represents a simplification of the involved processes whereby record men would come up with a title for an album. At one time in the not too distant past, the market was being glutted with such titles as "Music for Hip Lovers "...

- Levin, Harry (October 1977), "The Title as a Literary Genre", Modern Language Review, 72 (4): xxiii–xxxvi, doi:10.2307/3724776, JSTOR 3724776

- http://www.writersdigest.com/online-editor/do-you-underline-book-titles

- "APA Formatting and Style Guide". Purdue OWL. March 1, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- http://grammartips.homestead.com/titles.html

Further reading

- Adams, Hazard (Autumn 1987), "Titles, Titling, and Entitlement to", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 46 (1): 7–21, doi:10.2307/431304

- Adorno, Theodor (1984), "Titres", Notes sur la littérature, Paris

- Ferry, Anne (1996), The Title to the Poem, Stanford University Press, ISBN 9780804735179

- Fisher, John (December 1984), "Entitling", Critical Inquiry, 11 (2): 286–298, doi:10.1086/448289

- Genette, Gérard; Crampé, Bernard (Summer 1988), "Structure and Functions of the Title in Literature", Critical Inquiry, 14 (4): 692–720, doi:10.1086/448462, JSTOR 1343668

- Hélin, Maurice (September–December 1956), "Les livres et leurs titres", Marche Romane, 6: 139–152

- Hoek, Leo H. (1981), La marque du titre: Dispositifs sémiotiques d'une pratique textuelle, Approaches to Semiotics [AS], 60

- Kellman, Steven G. (Spring 1975), "Dropping Names: the Poetics of Titles", Criticism, 17 (2): 152–167

- Levin, Harry (October 1977), "The Title as a Literary Genre", The Modern Language Review, 72 (4): xxiii–xxxvi, doi:10.2307/3724776, JSTOR 3724776

- Levinson, Jerrold (Autumn 1985), "Titles", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 44 (1): 29–39, doi:10.2307/430537

- Mulvihill, John (April 1998), "For Public Consumption: The Origin of Titling the Short Poem", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 97 (2): 190–204, JSTOR 27711639

- Oliver, Revilo P. (1951), "The First Medicean MS of Tacitus and the Titulature of Ancient Books", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 82: 232–261, doi:10.2307/283436, JSTOR 283436

- Shevlin, Eleanor F. (1999), "'To Reconcile Book and Title, and Make 'em Kin to One Another': The Evolution of the Title's Contractual Functions", Book History, 2: 42–77, doi:10.1353/bh.1999.0011

- Sullivan, Ceri (July 2007), "Disposable Elements? Indications of Genre in Early Modern Titles", The Modern Language Review, 102 (3): 641–653, doi:10.2307/20467425, JSTOR 20467425

- Vardi, Amiel D. (May 1993), "Why Attic Nights? Or What's in a Name?", The Classical Quarterly, New Series, 43 (1): 298–301, doi:10.1017/S0009838800044360

- Wilsmore, S. J. (Summer 1987), "The Role of Titles in Identifying Literary Works", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 45 (4): 403–408, doi:10.2307/431331