Sefer Torah

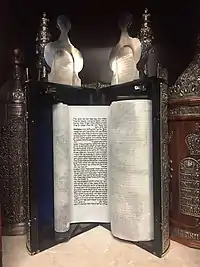

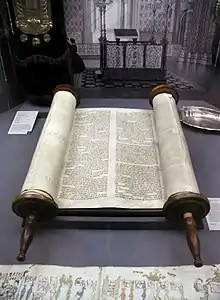

A Torah scroll, in Hebrew Sefer Torah (Hebrew: ספר תורה; "Book of Torah"; plural: ספרי תורה Sifrei Torah), is a handwritten copy of the Torah, meaning: of the Pentateuch, or the five books of Moses (the first books of the Hebrew Bible). It must meet extremely strict standards of production. The Torah scroll is mainly used in the ritual of Torah reading during Jewish prayers. At other times, it is stored in the holiest spot within a synagogue, the Torah ark, which is usually an ornate curtained-off cabinet or section of the synagogue built along the wall that most closely faces Jerusalem, the direction Jews face when praying.

The text of the Torah is also commonly printed and bound in book form for non-ritual functions. It is then known as a Chumash (plural Chumashim) ("five-part", for the five books of Moses), and is often accompanied by commentaries or translations.

History

The charred remains of a scroll found in the Torah niche of the ancient Ein Gedi synagogue, have been dated to ca. 300 CE.[1] The scroll was deciphered and the result shows that it contained one, two, or at the most three of the five books of Moses.[1] The researchers have concluded that by the fourth century CE, there was no halakhic rule yet prescribing that scrolls used for liturgical purposes must contain the entire Pentateuch.[1] No other statements regarding when this rule came to be observed, can be made with any degree of certainty.[1]

Usage

Torah reading from a Sefer Torah or Torah scroll is traditionally reserved for Monday and Thursday mornings, as well as for Shabbat and Jewish holidays. The presence of a quorum of ten Jewish adults (minyan) is required for the reading of the Torah to be held in public during the course of the worship services. As the Torah is sung, following the often dense text is aided by a yad ("hand"), a metal or wooden hand-shaped pointer that protects the scrolls by avoiding unnecessary contact of the skin with the parchment.

All Jewish prayers start with a blessing (berakhah), thanking God for Him revealing the Law to the Jews (Matan Torah), before Torah reading and all days during the first blessings (berakhot) of the morning prayer (Shacharit).[2]

Production

Rules

According to Jewish law (halakha), a Sefer Torah is a copy of the formal Hebrew text of the Torah hand-written on special types of parchment (see below) by using a quill or another permitted writing utensil, dipped in ink. Producing a Torah scroll fulfills one of the 613 commandments. "The k'laf/parchment on which the Torah scroll is written, the hair or sinew with which the panels of parchment are sewn together, and the quill pen with which the text is written all must come from ritually clean —that is, kosher— animals."[3]

Written entirely in Hebrew, a Torah scroll contains 304,805 letters, all of which must be duplicated precisely by a trained scribe, or sofer, an effort which may take as long as approximately one and a half years. An error during transcription may render the Torah scroll pasul ("invalid"). According to the Talmud, all scrolls must also be written on gevil parchment that is treated with salt, flour and m'afatsim (a residue of wasp enzyme and tree bark)[4] in order to be valid. Scrolls not processed in this way are considered invalid (Hilkoth Tefillin 1:8 & 1:14, Maimonides).

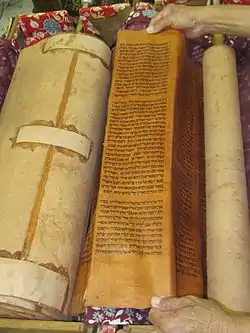

Parchment

There are only two types of kosher parchment allowed for a Torah scroll: gevil and klaf (see also above under "Rules").[3] The three types of specially processed animal skin or parchment that can be used are: gevil (a full, un-split animal hide), klaf (also qlaf or k'laf), and duchsustos, the latter two being one half of a split animal hide; arguably either the inner layer (adjacent to the flesh), or the outer layer (on which the hair grows). However, a Torah scroll written on duchsustos is not kosher. These are Hebrew words to describe different types of parchment, although the term duchsustos is Greek. These are used for the production of a mezuzah (religious text affixed to the doorpost), megillah (one of five texts from biblical "Writings"), tefillin (phylacteries), and/or a Torah scroll (sefer Torah). A kosher Torah scroll should be written on gevil. If klaf is used in place of gevil, the Torah scroll is still kosher, but this should not be done at the outset (l'chatchila).

The use of gevil and certain types of parchment has allowed some Torah scrolls of antiquity to survive intact for over 800 years.

The calfskin or parchment on which the sacred Hebrew text is written is mounted into a wooden housing called עץ חיים etz khayim, "Tree of Life" in Hebrew.

Ink

The ink used is subject to specific rules (see also above under "Rules") The ink used in writing scrolls had to adhere to a surface that was rolled and unrolled, so special inks were developed. Even so, ink would slowly flake off of scrolls. If the ink from too many letters is lost, a Torah scroll is no longer used.

Lines and columns

After the preparation of the parchment sheet, the scribe must mark out the parchment using the sargel ("ruler") ensuring the guidelines are straight. Only the top guide is done and the letters suspended from it.

Most modern Torah scrolls are written with forty-two lines of text per column (Yemenite Jews use fifty one). Very strict rules about the position and appearance of the Hebrew alphabet are observed. See for example the Mishnah Berurah on the subject.[5]

Script

Any of several Hebrew scripts may be used, most of which are fairly ornate and exacting. The fidelity of the Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular, is considered paramount, down to the last letter: translations or transcriptions are frowned upon for formal service use, and transcribing is done with painstaking care.

Scribal errors

Some errors are inevitable in the course of production. If the error involves a word other than the name of God, the mistaken letter may be obliterated from the scroll by scraping the letter off the scroll with a sharp object. If the name of God is written in error, the entire page must be cut from the scroll and a new page added, and the page written anew from the beginning. The new page is sewn into the scroll to maintain continuity of the document. The old page is treated with appropriate respect, and is buried with respect rather than being otherwise destroyed or discarded.

Completion

The completion of the Torah scroll is a cause for great celebration, and honoured guests of the individual who commissioned the Torah are invited to a celebration wherein each of the honored guests is given the opportunity to write one of the final letters. It is a great honour to be chosen for this.

Commandment to write a scroll

It is a religious duty or mitzvah for every Jewish male to either write or have written for him a Torah scroll. Of the 613 commandments, one – the 82nd as enumerated by Rashi, and the final as it occurs in the text the Book of Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 31:19) – is that every Jewish male should write a Torah scroll in his lifetime. This is law number 613 of 613 in the list of Laws of the Torah as recorded by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin in his book "Biblical Literacy", 1st edition, New York: Morrow 1997, p. 592: "The commandment that each Jew should write a Torah scroll during his lifetime."

It is considered a tremendous merit to write (or commission the writing of) a Torah scroll, and a significant honour to have a Torah scroll written in one's honour or memory.

Professional scribes (soferim)

In modern times, it is usual for some scholars to become soferim and to be paid to complete a Torah scroll under contract on behalf of a community or by individuals to mark a special occasion or commemoration. Because of the work involved, these can cost tens of thousands of United States dollars to produce to ritually proper standards.

Chumash vis-à-vis Torah scroll

A printed version of the Torah is known colloquially as a Chumash (plural Chumashim). Although strictly speaking it is known as Chamishah Chumshei Torah (Five "Fifths" of Torah). They are treated as respected texts, but not anywhere near the level of sacredness accorded a Torah scroll, which is often a major possession of a Jewish community. A chumash contains the Torah and other writings, usually organised for liturgical use, and sometimes accompanied by some of the main classic commentaries.

Torah ark, rollers, casing and decorations

A completed Torah scroll is treated with great honor and respect.

Torah ark

While not in use it is housed in the Torah ark (Aron Kodesh or Hekhal), which in its turn is usually veiled by an embroidered parochet, "curtain", as it should be according to Exodus 26:31–34.

External decorations

This ornamentation does not constitute worship of the Torah scroll, but is intended to distinguish it as sacred and holy, as the living word of God.

The gold and silver ornaments belonging to the scroll are collectively known as kele kodesh (sacred vessels), and somewhat resemble the ornaments of the High Priest of Israel (Kohen gadol).

The scroll itself will often be girded with a strip of silk (see wimpel) and "robed" with a piece of protective fine fabric, called the "Mantle of the Law". It is decorated with an ornamental priestly breastplate, scroll-handles (‘etz ḥayyim), and the principal ornament—the "Crown of the Law", which is made to fit over the upper ends of the rollers when the scroll is closed. Some scrolls have two crowns, one for each upper end. The metalwork is often made of beaten silver, sometimes gilded. The scroll-handles, breastplate and crown often have little bells attached to them (cf. rimmonim).

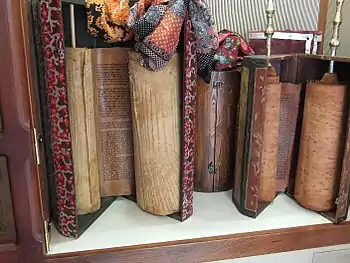

Mizrachi and Romaniote traditions

In the Mizrachi and Romaniote traditions, the Torah scroll is generally not robed in a mantle, but rather housed in an ornamental wooden case which protects the scroll, called a "tik", plural tikim. On the other hand, most Sephardic communities — those communities associated with the Spanish diaspora, such as Moroccan Jews, the Spanish and Portuguese Jews (with the exception of the Hamburg tradition[6]), and the Judaeo-Spanish communities of the Ottoman Empire — do not use tikim, but rather vestidos (mantles).

Rollers

The housing has two rollers, each of which has two handles used for scrolling the text, four handles in all. Between the handles and the rollers are round plates or disks which are carved with images of holy places, engraved with dedications to the donor's parents or other loved ones, and decorated with gold or silver.

The pointer (yad)

A yad, or pointer, may also be hung from the scroll, since the Torah itself should never be touched with the bare finger.

Inauguration

The installation of a new Torah scroll into a synagogue, or into the sanctuary or study hall (beth midrash) of a religious school (yeshiva), rabbinical college, university campus, nursing home, military base, or other institution, is done in a ceremony known as hachnosas sefer Torah, or "ushering in a Torah scroll"; this is accompanied by celebratory dancing, singing, and a festive meal.[7]

Biblical roots

This practice has its source in the escorting of the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem, led by King David. As described in the Books of Samuel, this event was marked by dancing and the playing of musical instruments (II Samuel 6:14–15). Both the priests or kohanim and David himself "danced before the Ark" or "danced before the Lord".[7][8]

Rituals at handling the scroll

Special prayers are recited when the Torah scroll is removed from the ark (see Torah reading), and the text is chanted, rather than spoken, in a special melodic manner (see Cantillation and Nigun). Whenever the scroll is opened to be read it is laid on a piece of cloth called the mappah. When the Torah scroll is carried through the synagogue, the members of the congregation may touch the edge of their prayer shawl (tallit) to the Torah scroll and then kiss it as a sign of respect.

See also

- Ashuri alphabet (Ktav Ashuri), the Aramaic alphabet adopted by Judaism

- Five Megillot (the "Five Scrolls"), parts of the Hebrew Bible traditionally grouped together

- Hakhel, biblical commandment to assemble for a Torah reading

- Ktav Stam, rules for writing ritual scrolls

- List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts - list of ancient scrolls and codices

- Tikkun (book), used to prepare for the reading of Torah scroll in synagogue

- Torah scroll (Yemenite), the specific Yemenite (as opposed to Ashkenazi or Sephardic) tradition of writing the Torah scroll

- Universal Torah Registry, an initiative to prevent Torah scroll theft

References

- Gary A. Rendsburg, The World’s Oldest Torah Scrolls, ANE Today, March 2018, Vol. VI, No. 3. Accessed 2 August 2019

- Rabbi Yehudah said: "They did not recite the blessings over the Torah before studying it!" (Talmud, Bava Metzia 85a-b)

- Essential Torah: A Complete Guide to the Five Books of Moses by George Robinson. (Schocken, 2006) ISBN 0-8052-4186-8. pp.10–11

- Handwritten 18th C. Hebrew Torah Scroll - from Morocco, Bidsquare, 11 Oct 2018, accessed 28 July 2019

- Mishnat Soferim The forms of the letters translated by Jen Taylor Friedman (geniza.net)

- Mosel, Wilhelm: “Synagoge der Portugiesisch-Jüdischen Gemeinde in Hamburg (Synagogue of the Portuguese-Jewish Community in Hamburg), situated at the rear of No. 6 of the former Zweite Marktstraße, later Marcusstraße.”

- Davidson, Baruch S. (2015). "Dedicating a New Torah Scroll". Chabad.org. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- van der Zande, Petra (2012). Remember Observe Rejoice: A Guide to the Jewish Feasts, Holidays, Memorial Days and Events. Tsur Tzina Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9789657542125.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Torah scrolls. |

- Three complete kosher Torah scrolls for study online (Congregation Beth Emeth of Northern Virginia)

- Torah scroll for study online with Megillot and commentaries

- Computer-generated Torah scroll for study online with translation, transliteration and chanting (WordORT)

- Scroll of the Law article from the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Examples of ancient Torah Scrolls

- ≈800-year-old Torah (pictures)

- Examples of Torah Covers Torah Mantles