Toilet god

A toilet god is a deity associated with latrines and toilets. Belief in toilet gods – a type of household deity – has been known from both modern and ancient cultures, ranging from Japan to ancient Rome. Such deities have been associated with health, well-being and fertility (because of the association between human waste and agriculture) and have been propitiated in a wide variety of ways, including making offerings, invoking and appeasing them through prayers, meditating and carrying out ritual actions such as clearing one's throat before entering or even biting the latrine to transfer spiritual forces back to the god.

Modern cultures

In Japan, belief in the toilet god or kawaya kami served a dual purpose. Most bodily wastes were collected and used as fertilizers, ensuring a higher overall level of sanitation than in other countries where wastes were stored in cesspits or otherwise disposed of. Toilets were often dark and unpleasant places where the user was at some risk of falling in and drowning. The protection of the toilet god was therefore sought to avoid such an unsanitary fate.[1]

The god also had a role to play in promoting fertility, as human waste was collected and used as fertiliser. Rituals were performed at the New Year to ask the kawaya kami for help in producing a good harvest. In some places, family members would sit on a straw mat in front of the toilet and eat a mouthful of rice, symbolising eating something that the god had left. A properly appointed toilet would be decorated and kept as clean as possible, as the toilet god was considered to be very beautiful. The state of the toilet was said to have an effect on the physical appearance of unborn children. Pregnant women asked the toilet god to give boys a "high nose" and dimples to girls. If the toilet was dirty, however, it was said to cause children to be born ugly and unhappy.[1] According to a different Japanese tradition, the toilet god was said to be a blind man holding a spear in his hand. This presented an obvious and painful threat when squatting down to defecate, so it was regarded as necessary to clear one's throat before entering so that the blind toilet god would sheathe his spear.[2]

Various rituals and names were associated with the latrine god in different parts of Japan. On Ishigaki Island it was called kamu-taka and was propitiated by the sick with sticks of incense, flowers, rice and rice wine. In Nagano Prefecture's former Minamiazumi District, sufferers from toothache offered lights to the toilet god, which was called takagamisama. The inhabitants of Hiroshima called the toilet god Setchinsan while those of Ōita Prefecture called it Sechinbisan and those of Ehime Prefecture called it Usshimasama.[3] The American anthropologist John Embree recorded in the 1930s that the inhabitants of part of the southernmost Japanese island of Kyūshū would put a branch of willow or Chinese nettle tree, decorated with pieces of mochi (rice cake), into the toilet as an offering to ask the toilet god to protect the house's inhabitants from bladder problems in the coming year.[4]

The Ainu people of far northern Japan and the Russian Far East believed that the Rukar Kamuy, their version of a toilet god, would be the first to come to help in the event of danger.[5]

In the Ryukyu Islands (including Okinawa Islands), the fuuru nu kami, or "toilet god", is the family protector of the area of waste. The pig toilet (ふーる / 風呂), lacking this benevolent god, could become a place of evil influence and potential haunting (such as by an akaname,[6] or other negative spirits, welcomed by the accumulation of waste matter, rejected and abandoned by the human body). Because he is considered a primary household god, the fuuru nu kami's habitat (the bathroom) is kept clean and is perceived to warrant deferential behavior. Reports on the family's status are delivered regularly to the fuuru nu kami. He shares traits with the Korean bathroom goddess Cheukshin.

Similarly in Korea, the toilet god or Cheukshin (or cheukgansin)[7] was known as the "young lady of the toilet".[8] She was regarded as having a "perverse character"[9] and was propitiated each year in October by housewives, along with the other household gods.[8]

A rather different form of toilet god existed in China, in the shape of Zi Gu 紫姑, also known as Mao Gu, the Lady of the Latrine or the Third Daughter of the Latrine. She was believed to be the spirit of a concubine who had been physically abused by a vengeful wife and had died in the latrine. Her cult appears to have originated in the Shanxi region and spread across China by the Tang period.[10] Women worshipped her in the form of a home-made doll on the fifteenth day of each year's first month, when she was ritually summoned in the latrine during the night. Prayers were said to the doll, telling her that the husband and wife had gone and that she could now safely come out. The motions of the doll – sometimes manifested as automatic writing – were used for fortune telling by the worshippers. Another interpretation came from a popular novel of the Ming period, which portrayed the latrine deity as three sisters who were responsible for the Primeval Golden Dipper (hunyuan jindou) or celestial toilet bowl, from which all beings were born.[11]

Some variants of Buddhism incorporate a belief in Ucchuṣma, the "god of the latrine", who is said to destroy defilement. A cult developed around Ucchuṣma in Zen monasteries where the latrine, the bath and the meditation hall or refectory were regarded as the three "silent places" (sanmokudō) for contemplation.[12]

In New Zealand, the atua – the gods and spirits of the Māori people – were believed to focus on the village latrine. If a warrior experienced sickness or faintness of heart or carried out an activity regarded as tapu, he would retreat to the latrine and bite its structure. The gods were said to frequent the latrine in large numbers and excrement was regarded as the food of the dead.[13] Biting the latrine was said to transfer the tapu quality that the biter had acquired back to its origins in the world of the gods. The practice of biting to transfer mana or tapu was seen in other areas of Māori life, such as a son biting his dead father's penis to acquire his powers, or a student weaver biting part of the loom to acquire tapu to assist with learning how to weave cloth.[14]

Ancient cultures

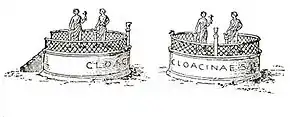

The inhabitants of ancient Rome had a sewer goddess, a toilet god and a god of excrement. The sewer goddess Cloacina (named from the Latin word cloaca or sewer) was borrowed from Etruscan mythology and became seen as the protectoress of the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's sewage system. An early Roman ruler, Titus Tatius, built a shrine to her in his toilet; she was invoked if sewers became blocked or backed up.[15] She was later merged with the better-known Roman goddess Venus and was worshipped at the Shrine of Venus Cloacina in the Roman Forum.[16]

Early Christians alleged the Romans to have had a toilet god in the form of Crepitus, who was also the god of flatulence and was invoked if a person had diarrhoea or constipation. There are no ancient references to Crepitus. They additionally propitiated Stercutius (named from stercus or excrement), the god of dung, who was particularly important to farmers when fertilising their fields with manure. He had a close relationship with Saturn, the god of agriculture.[15] Early Christians seem to have found Stercutius particularly ridiculous; he was a target of mockery for St. Augustine of Hippo in his book City of God in the early 5th century AD.[17]

In popular culture

Japanese singer-songwriter Kana Uemura had a 2010 Billboard chart-topping hit with "Toilet no Kamisama", a song about bonding with her grandmother over a goddess living in a toilet.

See also

- Pig toilet

- Hanako-san, a widespread Japanese urban legend about a ghost that inhabits toilets

- Šulak, Babylonian demon of the privy

- Tlazōlteōtl, Aztec goddess of filth, defecation, steam baths, and vice

References

- Hanley, Susan B. (1999). Everyday things in premodern Japan: the hidden legacy of material culture. University of California Press. pp. 122–125. ISBN 978-0-520-21812-3.

- Norbeck, Edward (1978). Country to city: the urbanization of a Japanese hamlet. University of Utah Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-87480-119-4.

- Yanigita, Kunio (1954). Japanese folk tales. Tokyo News Service. p. 128.

- Embree, John Fee (1939). Suye mura, a Japanese village. University of Chicago Press. p. 271.

- Shigeru, Kayano (2003). The Ainu: a story of Japan's original people. Tuttle Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8048-3511-4.

- Aka-name ~ 垢舐 (あかなめ) ~ part of The Obakemono Project: An Online Encyclopedia of Yōkai and Bakemono

- Korean Institute of Traditional Landscape Architecture (2007). Korean traditional landscape architecture. Hollym International. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-56591-252-6.

- Yi, Kwang-gyu (1997). Korean family and kinship. Jipmoondang Publishing Co. p. 208. ISBN 9788930350037.

- Koo, John H.; Nahm, Andrew C. (1997). An introduction to Korean culture. Hollym International. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-56591-086-7.

- Lust, John (1996). Chinese popular prints. BRILL. pp. 322–324. ISBN 978-90-04-10472-3.

- Kang, Xiaofei (2006). The cult of the fox: power, gender, and popular religion in late imperial and modern China. p. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13338-8.

- Faure, Bernard (1998). The red thread: Buddhist approaches to sexuality. Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-691-05997-6.

- Hanson, F. Allan; Hanson, Louise (1983). Counterpoint in Maori culture. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7100-9546-6.

- Hanson & Hanson (1983), ibid, p. 81

- Horan, Julie L. (1996). The porcelain god: a social history of the toilet. Carol Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-55972-346-6.

- Daly, Kathleen N.; Rengel, Marian (2009). Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-60413-412-4.

- Machado, Carlos (2011). "Roman aristocrats and the christianization of Rome". In Brown, Peter; Testa, Rita Lizzi (eds.). Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire: The Breaking of a Dialogue: (IVth-VIth Century A.D.): Proceedings of the International Conference at the Monastery of Bose (October 2008). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 523. ISBN 978-3-643-90069-2.