Tokyo Imperial Palace

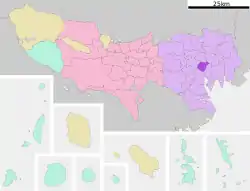

The Tokyo Imperial Palace (皇居, Kōkyo, literally 'Imperial Residence') is the main residence[1] of the Emperor of Japan. It is a large park-like area located in the Chiyoda district of the Chiyoda ward of Tokyo and contains several buildings including the main palace (宮殿, Kyūden), some residences of the Imperial Family, an archive, museums and administrative offices.

| Tokyo Imperial Palace | |

|---|---|

皇居 | |

Seimon Ishibashi bridge, which leads to the main gate of the Imperial Palace | |

Tokyo Imperial Palace | |

| Former names | Edo Castle |

| General information | |

| Address | 1-1 Chiyoda, Chiyoda-ku 100-0001 Tokyo |

| Town or city | Tokyo |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 35.6825°N 139.7521°E |

It is built on the site of the old Edo Castle. The total area including the gardens is 1.15 square kilometres (0.44 sq mi).[2] During the height of the 1980s Japanese property bubble, the palace grounds were valued by some to be more than the value of all of the real estate in the state of California.[3][4][5]

History

Edo castle

After the capitulation of the shogunate and the Meiji Restoration, the inhabitants, including the Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, were required to vacate the premises of the Edo Castle. Leaving the Kyoto Imperial Palace on 26 November 1868, the Emperor arrived at the Edo Castle, made it to his new residence and renamed it to Tōkei Castle (東京城, Tōkei-jō). At this time, Tōkyō had also been called Tōkei. He left for Kyōto again, and after coming back on 9 May 1869, it was renamed to Imperial Castle (皇城, Kōjō).[6]

Previous fires had destroyed the Honmaru area containing the old donjon (which itself burned in the 1657 Meireki fire). On the night of 5 May 1873, a fire consumed the Nishinomaru Palace (formerly the shōgun's residence), and the new imperial Palace Castle (宮城, Kyūjō) was constructed on the site in 1888. The castle has many gardens.

A non-profit "Rebuilding Edo-jo Association" (NPO法人 江戸城再建) was founded in 2004 with the aim of a historically correct reconstruction of at least the main donjon. In March 2013, Naotaka Kotake, head of the group, said that "the capital city needs a symbolic building", and that the group planned to collect donations and signatures on a petition in support of rebuilding the tower. A reconstruction blueprint had been made based on old documents. The Imperial Household Agency at the time had not indicated whether it would support the project.[8][9]

The Old palace

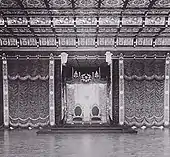

In the Meiji period, most structures from the Edo Castle disappeared. Some were cleared to make way for other buildings while others were destroyed by earthquakes and fire. For example, the wooden double bridges (二重橋, Nijūbashi) over the moat were replaced with stone and iron bridges. The buildings of the Imperial Palace constructed in the Meiji era were constructed of wood. Their design employed traditional Japanese architecture in their exterior appearance while the interiors were an eclectic mixture of then-fashionable Japanese and European elements. The ceilings of the grand chambers were coffered with Japanese elements; however, Western chairs, tables and heavy curtains furnished the spaces. The floors of the public rooms had parquets or carpets while the residential spaces used traditional tatami mats.

The main audience hall was the central part of the palace. It was the largest building in the compound. Guests were received there for public events. The floor space was more than 223 tsubo or approximately 737.25 m2 (7,935.7 sq ft). In the interior, the coffered ceiling was traditional Japanese-style, while the floor was parquetry. The roof was styled similarly to the Kyoto Imperial Palace, but was covered with (fireproof) copper plates rather than Japanese cypress shingles.

In the late Taishō and early Shōwa period, more concrete buildings were added, such as the headquarters of the Imperial Household Ministry and the Privy Council. These structures exhibited only token Japanese elements.

From 1888 to 1948, the compound was called Palace Castle (宮城, Kyūjō). On the night of 25 May 1945, most structures of the Imperial Palace were destroyed in the Allied firebombing raid on Tokyo. According to the US bomber pilot Richard Lineberger, Emperor's Palace was the target of their special mission on July 29, 1945, and was hit with 2000-pound bombs.[10][11] In August 1945, in the closing days of World War II, Emperor Hirohito met with his Privy Council and made decisions culminating in the surrender of Japan at an underground air-raid shelter on the palace grounds referred to as His Majesty's Library (御文庫附属室, Obunko Fuzokushitsu).[12]

Due to the large-scale destruction of the Meiji-era palace, a new main palace hall (宮殿, Kyūden) and residences were constructed on the western portion of the site in the 1960s. The area was renamed Imperial Residence (皇居, Kōkyo) in 1948, while the eastern part was renamed East Garden (東御苑, Higashi-Gyoen) and became a public park in 1968.

Interior images of the old Meiji-era palace

Higashidamari-no-Ma

Higashidamari-no-Ma Chigusa-no-Ma

Chigusa-no-Ma Hōmei-Den

Hōmei-Den Kiri-no-Ma

Kiri-no-Ma Nishidamari-no-Ma

Nishidamari-no-Ma Throne hall

Throne hall

Present palace

The present Imperial Palace encompasses the retrenchments of the former Edo Castle. The modern Kyūden (宮殿) designed for various imperial court functions and receptions is located in the old Nishinomaru section of the palace grounds. On a much more modest scale, the Fukiage Palace (吹上御所, Fukiage gosho), the official residence of the Emperor and empress, is located in the Fukiage Garden. Designed by Japanese architect Shōzō Uchii the modern residence was completed in 1993.[13] This residence is currently (July 2020) not in use and being prepared for Naruhito, who for the time being keeps his primary residence at the former Tōgū Palace, renamed Akasaka Palace (赤坂御所, Akasaka gosho) while he resides there.

Except for the Imperial Household Agency and the East Gardens, the main grounds of the palace are generally closed to the public, except for reserved guided tours from Tuesdays to Saturdays (which access only the Kyūden Totei Plaza in front of the Chowaden). Each New Year (January 2) and Emperor's Birthday, the public is permitted to enter through the Nakamon (inner gate) where they gather in the Kyūden Totei Plaza. The Imperial Family appears on the balcony before the crowd and the Emperor normally gives a short speech greeting and thanking the visitors and wishing them good health and blessings. Parts of the Fukiage garden are sometimes open to the general public.

The old Honmaru, Ninomaru, and Sannomaru compounds now comprise the East Gardens, an area with public access containing administrative and other public buildings.

The Kitanomaru Park is located to the north and is the former northern enceinte of Edo Castle. It is a public park and is the site of the Nippon Budokan. To the south is Kokyo Gaien National Garden.

Grounds

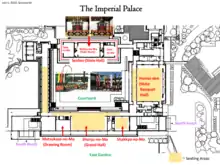

Kyūden

The Imperial Palace (宮殿, Kyūden) and the headquarters of the Imperial Household Agency are located in the former Nishinomaru enceinte (West Citadel) of the Edo Castle.[14]

The main buildings of the palace grounds, including the Kyūden (宮殿) main palace, home of the liaison conference of the Imperial General Headquarters, were severely damaged by the fire of May 1945. Today's palace consists of multiple modern structures that are interconnected. The palace complex was finished in 1968 and was constructed of steel-framed reinforced concrete structures produced domestically, with two stories above ground and one story below. The buildings of the Imperial Palace were constructed by the Takenaka Corporation in a modernist style with clear Japanese architectural references such as the large, gabled hipped roof, columns and beams.

The complex consists of six wings, including:

- Seiden State Function Hall

- Hōmeiden State Banquet Hall

- Chōwaden Reception Hall

- Rensui Dining Room

- Chigusa Chidori Drawing Room and

- The Emperor's work office

Halls include the Minami-Damari, Nami-no-Ma, multiple corridors, Kita-Damari, Shakkyō-no-Ma, Shunju-no-Ma, Seiden-Sugitoe (Kaede), Seiden-Sugitoe (Sakura), Take-no-Ma, Ume-no-Ma and Matsu-no-Ma.[15] Famous Nihonga artists such as Maeda Seison were commissioned to paint the artworks.

The Kyūden is used for both receiving state guests and holding official state ceremonies and functions. The Matsu-no-Ma (Pine Chamber) is the throne room. The Emperor gives audiences to the Prime Minister in this room, as well as appointing or dismissing ambassadors and Ministers of State. It is also the room where the Prime Minister and Chief Justice is appointed to office.

Fukiage Garden

The Fukiage Garden has carried the name since the Edo period and is used as the residential area for the Imperial Family.

The Fukiage Palace (吹上御所, Fukiage gosho), achieved in 1993, was used as the primary residence of Akihito from December 8, 1993 to March 2020. Currently (July 2020) not used and being refurbished, it will be the primary residence of Naruhito.

The Fukiage Ōmiya Palace (吹上大宮御所, Fukiage Ōmiya-gosho) in the northern section was originally the residence of Emperor Showa and Empress Kōjun and was called the Fukiage Palace. After the Emperor's death in 1989, the palace was renamed the Fukiage Ōmiya Palace and was the residence of the Empress Dowager until her death in 2000.[16] It is currently not in use.

The palace precincts include the Three Palace Sanctuaries (宮中三殿, Kyūchū-sanden). Parts of the Imperial Regalia of Japan are kept here and the sanctuary plays a religious role in imperial enthronements and weddings.

East Gardens

The East Gardens is where most of the administrative buildings for the palace are located and encompasses the former Honmaru and Ninomaru areas of Edo Castle, a total of 210,000 m2 (2,300,000 sq ft). Located on the grounds of the East Gardens is the Imperial Tokagakudo Music Hall, the Music Department of the Board of Ceremonies of the Imperial Household, the Archives and Mausolea Department Imperial Household Agency, structures for the guards such as the Saineikan dojo, and the Museum of the Imperial Collections.

Several structures that were added since the Meiji period were removed over time to allow construction of the East Garden. In 1932, the kuretake-ryō was built as a dormitory for imperial princesses, however this building was removed prior to the construction of the present gardens. Other buildings such as stables and housing were removed to create the East Garden in its present configuration.

Construction work began in 1961 with a new pond in the Ninomaru, as well as the repair and restoration of various keeps and structures from the Edo period. On 30 May 1963, the area was declared by the Japanese government a "Special Historic Relic" under the Cultural Properties Protection Law.

Tōkagakudō (Music Hall)

The Tōkagakudō (桃華楽堂, Peach Blossom Music Hall) is located to the east of the former main donjon of Edo Castle in the Honmaru. This music hall was built in commemoration of the 60th birthday of Empress Kōjun on 6 March 1963. The ferro-concrete building covers a total area of 1,254 m2 (13,500 sq ft). The hall is octagon-shaped and each of its eight outer walls is decorated with differently designed mosaic tiles. Construction began in August 1964 and was completed in February 1966.

Ninomaru Garden

Symbolic trees representing each prefecture in Japan are planted in the northwestern corner of Ninomaru enceinte. Such trees have been donated from each prefecture and there are total of 260, covering 30 varieties.

The small Ninomaru Garden at the foot of the castle hill was originally planted in 1636 by Kobori Enshu, a famed landscape artist and garden designer, but it was destroyed by fire in 1867. The current layout was created in 1968, based on a plan drawn up during the reign of ninth shogun, Tokugawa Ieshige.[17]

Suwa no Chaya

The Suwa no Chaya (諏訪の茶屋) is a teahouse that was located in the Fukiage Garden during the Edo period. It moved to the Akasaka Palace after the Meiji restoration, but was reconstructed in its original location in 1912.

It was moved to its present location during the construction of the East Garden.

Kitanomaru

The Kitanomaru Park is located to the north and is the former northern enceinte of Edo Castle. It is a public park and is the site of Nippon Budokan Hall.

This garden contains a bronze monument to Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王, Kitashirakawa-no-miya Yoshihisa-shinnō).

Kōkyo-gaien

To the south-east are the large outer gardens of the Imperial Palace, which are also a public park and contain bronze monuments to Kusunoki Masashige (楠木正成) and to Wake no Kiyomaro (和気清麻呂).

Gallery

Ote-mon gate and main entrance to the "East Garden"

Ote-mon gate and main entrance to the "East Garden" Imperial Palace moat and guard tower

Imperial Palace moat and guard tower Imperial Palace front entrance field with Chiyoda office buildings in the background

Imperial Palace front entrance field with Chiyoda office buildings in the background Building of the Imperial Household Agency on the grounds of the Imperial Palace

Building of the Imperial Household Agency on the grounds of the Imperial Palace Suwa no chaya teahouse in the Ninomaru Garden

Suwa no chaya teahouse in the Ninomaru Garden Saineikan dōjō for the guards

Saineikan dōjō for the guards Building of the former Privy Council in the East Garden area, one of the few buildings from the pre-war Showa period

Building of the former Privy Council in the East Garden area, one of the few buildings from the pre-war Showa period It is the privilege of each new ambassador arriving at the palace to hand in his or her accreditation to the Emperor to be picked up from Tokyo Station either in a limousine or the carriage. Although the carriage is not as comfortable as the modern limousine, most choose the carriage.

It is the privilege of each new ambassador arriving at the palace to hand in his or her accreditation to the Emperor to be picked up from Tokyo Station either in a limousine or the carriage. Although the carriage is not as comfortable as the modern limousine, most choose the carriage. Music Department of the Board of Ceremonies

Music Department of the Board of Ceremonies Museum of the Imperial Collections

Museum of the Imperial Collections Archives and Mausolea Department

Archives and Mausolea Department The moat of the Imperial Palace in spring

The moat of the Imperial Palace in spring Public walkway, Edo East Garden

Public walkway, Edo East Garden Moat of the Imperial Palace

Moat of the Imperial Palace Meeting between Emperor Akihito and then U.S. President George W. Bush

Meeting between Emperor Akihito and then U.S. President George W. Bush One of the entrances for supporting staff buildings

One of the entrances for supporting staff buildings Fujimi-yagura (Mt Fuji-view keep), guard building within the inner grounds of the Imperial Palace

Fujimi-yagura (Mt Fuji-view keep), guard building within the inner grounds of the Imperial Palace Pond in the East Garden at the Imperial Palace

Pond in the East Garden at the Imperial Palace Mounted Imperial Police around the Imperial Palace

Mounted Imperial Police around the Imperial Palace

References

- The Emperor currently (July 2020) does not have his residence in the Imperial Palace, but in the Akasaka Palace of the Akasaka Estate.

- "皇居へ行ってみよう". Kunai-chō. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- Mueller, Dennis C. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Capitalism. Oxford University Press. p. 497. ISBN 9780199942596. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Ian Cowie (7 August 2004). "Oriental risks and rewards for optimistic occidentals". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- Edward Jay Epstein (17 February 2009). "What Was Lost (and Found) in Japan's Lost Decade". Vanity Fair. VF Daily. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- 皇居 ‐ 通信用語の基礎知識. Wdic.org (in Japanese). 2010-02-04. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Tom (2015-09-27). "Lovely 1908 Photo of the Tokyo Imperial Palace". Cool Old Photos. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Rebuilding "Edo-jo" Association". Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- Daily Yomiuri NPO wants to restore Edo Castle glory March 21, 2013

- Richard C. L., Lineberger, "The Night We Bombed the Emperor's Palace," Air Power History, 50/3, (September 22, 2003) : 42 pages.

- The Free Library by Farlex, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+night+we+bombed+the+Emperor%27s+Palace-a0108551529

- "Time Wears on Imperial Shelter". The Japan News. Yomiuri Shimbun. 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "The Imperial Residence". The Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Takahiro Fukada (20 January 2010). "Imperial Palace resides in otherworldly expanse: History abounds in cultural and religious preserve in heart of metropolis". The Japan Times. p. 3.

- "The Imperial Palace: Photos". kunaicho.go.jp. Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- "The Imperial Palace and other Imperial Household Establishments". Imperial Household Agency. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- "Ninomaru and San-nomaru - Tokyo Cultural Heritage Map". Tokyo Cultural Heritage Map, Tokyo Metropolitan Board of Education. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |