Tomas O'Crohan

Tomás Ó Criomhthain (pronounced [t̪ˠɔˈmˠaːsˠ oː ˈkɾˠɪhən̠ʲ];[1] 21 December 1856 – 7 March 1937), anglicised as Tomas O'Crohan or Thomas O'Crohan, was a native of the Irish-speaking Great Blasket Island 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) off the coast of the Dingle Peninsula in Ireland. He wrote two books, Allagar na h‑Inise (Island Cross-Talk) written over the period 1918–23 and published in 1928, and An t‑Oileánach (The Islandman), completed in 1923 and published in 1929. Both have been translated into English.[2] The 2012 translation by Garry Bannister and David Sowby is to date the only unabridged version available in English (earlier versions were redacted, being considered too earthy).

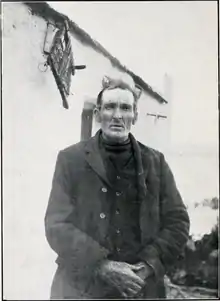

Tomás Ó Criomhthain | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Tomás Ó Criomhthain | |

| Born | 21 December 1856 |

| Died | 7 March 1937 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Notable works | Allagar na hInise |

| Spouse | Máire Ní Chatháin |

Writings

His books are considered classics of Irish-language literature containing portrayals of a unique way of life, now extinct, of great human, literary, linguistic, and anthropological interest. His writing is vivid, absorbing and delightful, full of incident and balance, fine observation and good sense, elegance and restraint.

He began to write down his experiences in diary-letters in the years after World War I, following persistent encouragement by Brian Ó Ceallaigh from Killarney. Ó Ceallaigh overcame Ó Criomhthain's initial reluctance by showing him works by Maxim Gorky and Pierre Loti, books describing the lives of peasants and fishermen, to prove to Ó Criomhthain the interest and value of such a project. Once persuaded, Ó Criomhthain sent Ó Ceallaigh a series of daily letters for five years – a diary – which the latter forwarded to scholar and writer Pádraig "An Seabhac" Ó Siochfhradha for editing for publication. Ó Ceallaigh then convinced Ó Criomhthain to write his life story and best-known work, An t-Oileánach.

Family

Ó Criomhthain had four sisters, Maura, Kate, Eileen and Nora, and a brother, Pats. His personality was well-grounded in intimate affection and respect for his parents who lived to a ripe old age. The only, minor, disharmony arose between himself and Nora who was five years his elder. She had been the family favourite until Tomás arrived "unexpectedly". Her jealousy of him created friction between them.

He married Máire Ní Chatháin in 1878. She bore ten children but many died before reaching adulthood: One boy fell from a cliff while hunting for a fledgling gull to keep as a pet among the chickens; others died of measles and whooping cough; their son Domhnall drowned while attempting to save a woman from the sea; others were taken by other misfortunes. Máire herself died while still relatively young. Their son Seán also wrote a book, Lá dar Saol (A Day in Our Life), describing the emigration of the remaining islanders to the mainland and America when the Great Blasket was finally abandoned in the 1940s and 1950s.

Education

Ó Criomhthain received an intermittent education between the ages of 10 and 18 whenever a schoolteacher from the mainland lived for a while on the island. The teachers were usually young women who returned to the mainland on receiving proposals of marriage. He had a long childhood of enviable liberty from drudgery without the constant confinements of the classroom or a grinding programme of chores from which he was spared by having five older siblings.

Life and experiences

As a fisherman, Ó Criomhthain caught a wide variety of seafood, including scad, pilchard, mackerel, cod, herring, halibut, pollock, bream, dogfish, ling, rockfish, wrasse, conger eel, porpoises ("sea pig" and "sea bonham" – the meat being described as "pork"), seals, crab, lobster, crayfish, limpets, winkles and mussels, as well as seaweeds such as dulse, sea lettuce, sea belt, and murlins. Many on the island relished seal meat much more than pork. One night Ó Criomhthain and colleagues caught a "huge creature" in their nets with great danger and difficulty. Perhaps it was a whale or basking shark. Oil from the liver of this unidentified "great beast" fuelled all the lamps on the island for five years (there were about 150 people in fewer than 30 households).

Ó Criomhthain harvested turf for home fuel from the top of the island, and the sods were carried home by an ass. When he set to work cutting turf, he was often interrupted by the island poet who distracted him by teaching him his lengthy songs. There is much comedy in Ó Criomhthain's silent exasperation at the hours wasted, yet he never snubbed the poet for fear a damaging satire would be composed against him.

In addition to fish and other "sea fruit" Ó Criomhthain's diet included potatoes, milk, lumps of butter, porridge, bread, rabbits, sea birds, eggs, and mutton. The few acres of arable land on the island were fertilised with dung and seaweed, supplemented by chimney-soot and mussel shells. The limited crops sown included potatoes and a few other vegetables, along with oats and rye. The island was alive with rabbits which were easily caught in great numbers and the hunting was sometimes assisted by dogs or a ferret. Birds hunted for their meat and eggs included gulls, puffins, gannets, petrels, shearwaters, razorbills and guillemots.

The roof of his home was made of a thatch of rushes or reeds and his sisters would climb up to collect eggs from under the hens nesting on top. One amusing episode in An t-Oileánach describes a neighbour's family at supper when, to their bewilderment and consternation, young chickens began raining, one by one, onto the table and splashing into a mug of milk. "For God's sake," cried the woman of the house, "where are they coming from?" One of the children spied a hole scratched in the roof by a mother hen.

Ó Criomhthain lived in a cottage or stone cabin with a hearth at the kitchen end and sleeping quarters at the other. A feature of island life much remarked upon by mainland readers of his books was the keeping of animals in kitchens at night, including cows, asses, sheep, dogs, cats and hens.

He was a keen collector of old tales and described a conversation between his father and a neighbour at the hearth one night. Once when at sea his father, the neighbour and other fishermen saw a steamship sail by. They had never seen one before, and naturally assumed it was on fire. They rowed after it to render assistance, but failed to catch it.

"We might have known," said my father, "since the ship was moving, that there was something driving her and that she wasn't on fire at all, as there was no wind and she had no sails up, and we were following in our boats rowing our guts to catch her, without getting any nearer."

The islanders' sometimes meagre existence was often supplemented by gifts from the sea when shipwrecks occurred. One such incident materialized when Ó Criomhthain was out fishing for lobsters with his brother, Pats. He describes the encounter, writing:

"When we started there were some spars of drift timber to be seen. We picked them up. There were some more to be seen in other places... By this time the two of us had saved about three-score white planks... The talk of the village was the quantity of timber that the two of us, with our little canoe, had collected in Beginish, and for many days after that we found planks and fragments and pieces of timber."

In that one shipwreck, Ó Criomhthain and his brother made about a dozen pounds, which was a substantial sum of money in their world. In addition to timber, copper and brass were salvaged, as well as cargoes of food such as meal and wheat, which helped them to survive lean years. At one time tea was unknown on the island, and when a cargo of the stuff floated ashore from a wreck it was used by one woman to dye her flannel petticoats (normally dyed with woad). She also used it to feed pigs. A neighbour was incensed that her husband didn't bother to salvage a chest of this useful stuff for her; she too had petticoats waiting to be dyed and hungry pigs to feed. She scolded her husband so severely that he quit the island without a word, never to be seen again. Later, another application for tea leaves was discovered and it became a popular drink for the human population.

Ó Criomhthain ended An t-Oileánach with a statement whose final clause is well known and often quoted in Ireland:

I have written minutely of much that we did, for it was my wish that somewhere there should be a memorial of it all, and I have done my best to set down the character of the people about me so that some record of us might live after us, for the like of us will never be again.

—An t-Oileánach, final chapter

Works

- Allagar na hInise, ISBN 1-85791-131-8 (in Irish)

- Allagar 11, Coiscéim 1999 Edited by Pádraig Ua Maoileoin

- An tOileánach, Cló Talbóid 2002, ISBN 0-86167-956-3 (in Irish)

- "Stair na mBlascaodaí, beag agus mór" (Manuscript images). UCD Digital Library (in Irish). University College Dublin. 2007 [1930].

- Translations

- Island Cross-Talk: Pages from a Diary, translated by Tim Enright; Oxford University Press, 1987; ISBN 0-19-212252-5

- The Islandman, translated by Robin Flower; Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1951; ISBN 0-19-815202-7

- The Islander, translated by Garry Bannister and David Sowby; Gill & MacMillan, 2013; ISBN 0-71-715794-6

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tomás Ó Criomhthain. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Ó Criomhthain's Ricorso database entry

- An Béal Bocht

- Blasket Islands

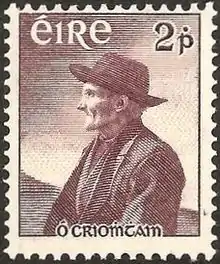

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- The Blascaod Centre in Dún Chaoin

References

- An t-Oileánach (in Irish) (fifth ed.). Comhlacht Oideachas na hÉireann. 1969.

- Tomás Ó Criomthain (1856–1937) Archived 25 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Ricorso. Retrieved: 29 November 2011.