Máirtín Ó Cadhain

Máirtín Ó Cadhain ([ˈmaːɾʲ.tʲiːnʲ oː ˈkəinʲ]; 1906 – 18 October 1970) was one of the most prominent Irish language writers of the twentieth century. Perhaps best known for his 1949 work Cré na Cille, Ó Cadhain played a key role in bringing literary modernism to contemporary Irish language literature. Politically, he was an Irish nationalist and socialist, promoting the Athghabháil na hÉireann ("Re-Conquest of Ireland"), through Gaelic culture. He was a member of the post-Civil War Irish Republican Army with Brendan Behan during the Emergency.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1906 An Spidéal, County Galway, Ireland |

| Died | 18 October 1970 (aged 64) Dublin, Republic of Ireland |

| Resting place | Mount Jerome Cemetery |

| Pen name | Aonghus Óg Breallianmaitharsatuanógcadhanmaolpote D. Ó Gallchobhair Do na Fíréin Micil Ó Moingmheara M.Ó.C[1] |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, journalist, school teacher |

| Language | Irish (Connacht Irish) |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Period | 1932–1970 |

| Genre | Fiction, politics, linguistics, experimental prose[2] |

| Subject | Irish Republicanism, modern Irish prose |

| Literary movement | Modernism, social radicalism |

| Notable works | Cré na Cille, An Braon Broghach, Athnuachan |

| Spouse | Máirín Ní Rodaigh |

| Relatives | Seán Ó Cadhain (father), Bríd Nic Conaola[3] (mother) |

Literary career

Born in Connemara, he became a schoolteacher but was dismissed due to his Irish Republican Army (IRA) membership. In the 1930s he served as an IRA recruiting officer, enlisting fellow writer Brendan Behan.[4] During this period, he also participated in the land campaign of native speakers, which led to the establishment of the Ráth Cairn neo-Gaeltacht in County Meath. Subsequently, he was arrested and interned during the Emergency years on the Curragh Camp in County Kildare, due to his continued involvement in the IRA.[5]

Ó Cadhain's politics were a nationalist mix of Marxism and social radicalism tempered with a rhetorical anti-clericalism. In his writings concerning the future of the Irish language he was practical about the position of the Church as a social and societal institution, seeking commitment to the language cause even from Catholic churchmen. It was his view that, as the Church was there anyway, it would be better if it were more willing to address its adherents in the Irish language.

As a writer, Ó Cadhain is acknowledged to be a pioneer of Irish-language modernism. His Irish was the dialect of Connemara, and he was often accused of an unnecessarily dialectal usage in grammar and orthography even in contexts where realistic depiction of Connemara dialect wasn't called for. But he was also happy to cannibalise other dialects, classical literature and even Scots Gaelic for the sake of the linguistic and stylistic enrichment of his own writings. Consequently, much of what he wrote is reputedly hard to read for a non-native speaker.

He was a prolific writer of short stories. His collections of short stories include Cois Caoláire, An Braon Broghach, Idir Shúgradh agus Dháiríre, An tSraith Dhá Tógáil, An tSraith Tógtha and An tSraith ar Lár. He also wrote three novels, of which only Cré na Cille was published during his lifetime. The other two, Athnuachan and Barbed Wire, appeared in print only recently. He translated Charles Kickham's novel Sally Kavanagh into Irish as Saile Chaomhánach, nó na hUaigheanna Folmha. He also wrote several political or linguo-political pamphlets. His political views can most easily be discerned in a small book about the development of Irish nationalism and radicalism[6] since Theobald Wolfe Tone, Tone Inné agus Inniu; and in the beginning of the sixties, he wrote – partly in Irish, partly in English – a comprehensive survey of the social status and actual use of the language in the west of Ireland, published as An Ghaeilge Bheo – Destined to Pass. In August 1969 he delivered a speech (published as Gluaiseacht na Gaeilge: Gluaiseacht ar Strae) in which he spoke of the role Irish speakers should take in 'athghabháil na hÉireann', or the 'reconquest of Ireland' as James Connolly first coined the term.

He and Diarmaid Ó Súilleabháin were considered the two most innovative Irish language authors to emerge in the 1960s.[7] Ó Cadhain had frequent difficulties getting his work edited, but unpublished writings have appeared at least every two years since the publication of Athnuachan in the mid-nineties.

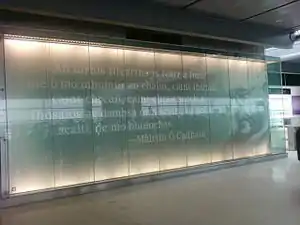

A lecture hall in Trinity College Dublin is named after Ó Cadhain[8] who was professor of Irish there.[9] There is also a bronze bust of him in the Irish department of the university.

Political activity

Ó Cadhain's interest in Irish republicanism grew after he started reading An Phoblacht, a republican newspaper with strong links to the Irish Republican Army that publishes articles in both English and Irish. While living in Camus, County Galway (an Irish-speaking Gaeltacht village) he resided with Seosamh Mac Mathúna, who had been a member of the IRA since 1918. His time with Mac Mathúna further brought him down the path of republicanism and eventually, Mac Mathúna brought O Cadhain into the IRA.[10] As a member, he championed a Marxist analysis of Ireland and was a particular advocate for "Athghabháil na hÉireann" (English: "The Reconquest of Ireland"), a concept of James Connolly's that suggests the Irish language could only be saved by socialism, as the English language is a tool of the capitalists.[11][12]

In 1932 Ó Cadhain along with Mac Mathúna and Críostóir Mac Aonghusa (a local teacher, activist and county councillor) founded Cumann na Gaedhealtachta (The Gaeltacht Association), a pressure group to lobby on behalf of those living in Ireland's Gaeltacht areas. He formed a similar group in 1936 called Muinntir na Gaedhealtachta (the Gaeltacht People). One of the successes of these groups was the establishment of the Ráth Chairn Gaeltacht, in which a new Irish-speaking community was created in County Meath. Ó Cadhain had argued the only way by which Irish language speakers could thrive was if efforts to promote the language was coupled with giving Irish speakers good land to work, so as to give them an opportunity at economic success as well.[10]

By 1936, Ó Cadhain had been working as a school teacher in Carnmore, County Galway for four years, when he was dismissed from his post by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Galway for his republican beliefs, which were deemed to be "subversive". He had recently attended a commemoration in Bodenstown to honour his idol Wolfe Tone, which had been banned by the government. He subsequently moved to Dublin, where he acted as a recruiter for the IRA, at which he was quite successful. In April 1938 he was appointed to the IRA's Army Council and became their secretary. By 1939 he was "on the run" from the Irish authorities and by September of the year had been arrested and imprisoned until December. Ó Cadhain's stint with the Army Council was short-lived however; he resigned in protest of the S-Plan, a sabotage campaign against the British state during World War II, the grounds that any attempt to "liberate" Northern Ireland politically was meaningless unless the people were also "economically liberated".[11]

In 1940 he gave an oration at the funeral of his friend Tony Darcy, who had died on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison seeking political prisoner status. Following the funeral he was once again arrested and imprisoned, this time to spend four years with hundreds of other IRA members in the Curragh. Ó Cadhain's friend Tomás Bairéad campaigned for his release and they found success on 26 July 1944 when Ó Cadhain was allowed to leave. During Ó Cadhain's time in the Curragh, he taught many of the other prisoners the Irish language.[10][13]

Following his time in the Curragh, Ó Cadhain pulled back from politics to focus on his writing. For a long period he became bitter about Irish republicanism, but by the 1960s once again identified with its outlook. At the onset of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, he welcomed resistance to British rule as well as the idea of an armed struggle, and once again stated his Marxist outlook on the situation; "capitalism must go as well as the Border".

During the 1960s he once again threw himself into campaigning on behalf of the Irish language, this time with the group Misneach ("Courage"). The group resisted efforts by reform groups to no longer make it compulsory for a student to pass an Irish examination to receive a Leaving Certificate, as well as a requirement that those seeking employment in the public sector needed to be able to speak Irish. Misneach used civil disobedience tactics influenced by Saunders Lewis, the Welsh language advocate and founder of Plaid Cymru.[10]

Ó Cadhain was a key figure in the 1969 civil rights movement, Gluaiseacht Chearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta.

Personal life

He died on 18 October 1970 in Dublin and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery.

Works

Novels

- Athnuachan. Coiscéim. Baile Átha Cliath 1995 (posthumous)

- Barbed Wire. Edited by Cathal Ó hÁinle. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2002 (posthumous)

- Cré na Cille. Sáirséal agus Dill, Baile Átha Cliath 1949/1965.

- Translated as The Dirty Dust. Yale Margellos, New Haven 2015; Graveyard Clay. Yale Margellos, New Haven 2016.

Short story collections

- An Braon Broghach. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1991

- Cois Caoláire. Sáirséal – Ó Marcaigh, Baile Átha Cliath 2004

- Idir Shúgradh agus Dáiríre. Oifig an tSoláthair, Baile Átha Cliath 1975

- An tSraith dhá Tógáil. Sáirséal agus Dill, Baile Átha Cliath 1970/1981

- An tSraith Tógtha. Sáirséal agus Dill, Baile Átha Cliath 1977

- An tSraith ar Lár. Sáirséal Ó Marcaigh, Baile Átha Cliath 1986

- The Road to Brightcity. Poolbeg Press, Dublin 1981

- Dhá Scéal / Two Stories. Arlen House, Galway 2007

- An Eochair / The Key. Dalkey Archive Press, Dublin 2015

- The Dregs of the Day. Yale University Press, New Haven 2019

Journalism and miscellaneous writings

- Caiscín. (Articles published in the Irish Times 1953–56. Edited by Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh.) Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1998

- Tone Inné agus Inniu. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1999

- Ó Cadhain i bhFeasta. Edited by Seán Ó Laighin. Clódhanna Teoranta, Baile Átha Cliath 1990

- An Ghaeilge Bheo – Destined to Pass. Edited by Seán Ó Laighin. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2002.

- Caithfear Éisteacht! Aistí Mháirtín Uí Chadhain in Comhar (i.e. Máirtín Ó Cadhain's essays published in the monthly magazine Comhar). Edited by Liam Prút. Comhar Teoranta, Baile Átha Cliath 1999

See also

- Pádraic Ó Conaire, earlier Irish language modernist

- Muintir na Gaeltachta, co-founded by Ó Cadhain

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.questia.com/library/1G1-156808754/mairtin-o-cadhain-s-cre-na-cille-a-narratological%5B%5D

- as réamhleathanaigh An tSraith ar Lár

- Ó Cadhain at Ricorso

- Reporter (20 October 1970), "Obituary", The Irish Times, p. 13

- http://www.iar.ie/Archive.shtml?IE%20TCD%20MS/10878

- The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 476. ISBN 978-1-59884-964-6.

- Trinity Web Site reference to the facilities in the Uí Chadhain Teathre TCD Archived 18 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Seanad Éireann Proceedings – referencing ó Cadháin as Professor in TCD Archived 25 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Ní Ghallchobhair, Fidelma. "Ó Cadhain's life". máirtínócadhain.ie. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- O'Cathasaigh, Aindrias (18 October 2011). "Listening to Máirtín Ó Cadhain". lookleftonline.org. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "HISTORY: Remembering Máirtín Ó Cadhain". dublinpeople.com. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

By now Ó’Cadhain was a committed Marxist. For him, the decline of the Irish language and the utter neglect of Gaeltacht communities by the Irish Free State was a class issue. The language could only be restored through the ‘Re-conquest of Ireland’. Ó Cadhain began to encourage Irish speakers across the country to adopt socialism as the only viable method to save both the language and the struggling Gaeltacht communities.

- Breathnach, Diarmuid; Ní Mhurchú, Máire. "Ó CADHAIN, Máirtín (1906–1970)". ainm.ie (in Irish). Retrieved 24 November 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Máirtín Ó Cadhain. |