Tomb of Meryra

The Tomb of Meryra is part of a group of tombs located near Amarna, Upper Egypt. Placed in the mountainsides, the graves are divided into north and south groupings; the northern tombs are located in the hillsides and the southern on the plains. Meryra's burial, identified as Amarna Tomb 4 is located in the northern cluster. The sepulchre is the largest and most elaborate of the noble tombs of Amarna. It, along with the majority of these tombs, was never completed.[1] The rock cut tombs of Amarna were constructed specifically for the officials of King Akhenaten. Norman de Garis Davies originally published details of the Tomb in 1903 in the Rock Tombs of El Amarna, Part I – The Tomb of Meryra. The tomb dates back to the 18th Dynasty.

| Meryra in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Tomb layout

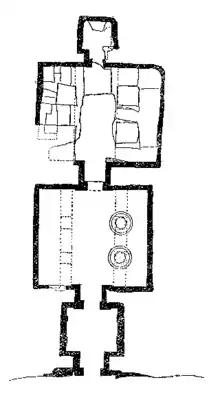

The tomb was found in relatively good condition compared to the other tombs of Amarna. After the death of Akhenaten, depictions of his rule and religion were destroyed because they were considered to be heretical. In Meryra’s tomb, Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s features have been consistently erased. The desecration is confined to these individuals, and the names and figures of the princesses remain untouched. The tomb consists of four sections: the antechamber, the hall of columns, a second hall, and the shrine. The entrance to the tomb was originally decorated with inscriptions to the Amarna Royal family and the deity Aten. These decorations have either been destroyed, or are hidden by the modern doors protecting the tomb entrance. The antechamber itself shows Meryre offering prayers to the Akhenaten, and the cartouches of the king, Nefertiti and the Aten. The door jambs are inscribed with funerary prayers for Akhenaten and the Aten. The entrance from the antechamber to the outer hall is decorated with the Short Hymn to the Aten, and shows Meryre's wife Tenre making offerings to the sun-disc.

Meryra

Meryra served as the high priest of the cult of Aten, a new religious tradition instituted by King Akhenaten. This belief system placed exclusive emphasis on sun worship in the form of Aten, or the solar disc, a deity encapsulating the idea of many gods into the essence of the sun.[2] The tomb provides little information regarding the personal life of Meryra. Familial references are limited to depictions of his wife, Tenre, who is described as “a great favorite of the Lady of the two Lands.” Lady of the two Lands refers to Nefertiti, the queen of Akhenaten. Not all officials at Amarna had tombs. Having a tomb at Amarna reflected closeness with Akhenaten, due, in part, to demonstrating a commitment to Akhenaten’s institution of Atenism.[1]

Tomb decorations

The sculptured reliefs of Meryra’s tomb were done in a new artistic style instituted under Akhenaten. The technique of modeling in plaster which was used consisted of the images initially being cut directly into the stone, and then covered by a layer of plaster, which was finally painted over.[3] Like the style, the subject of the scenes was also unique. Traditionally, tombs in the New Kingdom contained decorations dedicated to the owner of the tomb, such as depictions of family members and ancestors, or scenes about the owner’s career, amusement or domestic life.[3] This tradition was not carried out in the tomb of Meryra, or the other tombs of Amarna, which instead focused almost exclusively on Akhenaten and worship of the Aten. Davies acknowledges the tombs of Amarna were often difficult to identify as little emphasis was placed on the owner. This contrasts sharply with the dominant tradition of New Kingdom tombs in which cartouches and images of the ruling king were marginal aspects to the tomb, sometimes not even identified.[3]

The reliefs in the Tomb of Meryra are decidedly centered upon praising Akhenaten, and Meryra himself only appears marginally, sometimes indistinguishable from other minor figures carved in the relief. Despite this, Meryra maintains a constant contextual presence in the scenes, even if not being explicitly portrayed. In the scene Davies titles "A Royal Visit to the Temple", Akhenaten and Nefertiti are depicted paying a visit to Meryra at the temple. It is uncertain if Meryra is included in this image and the description of the scene has been destroyed. Davies speculates that the scene either shows Akhenaten on his way to the temple to appoint Meryra as the High Pries of Aten, or it is simply as example of Meryra honored with the presence of the King and Queen at the temple and exercising his office for them. Either situation serves to promote the role and importance of Meryra, even though the scene seems to be immediately focused upon Akhenaten. As the art was not focused upon Meryra, maintaining a strong contextual importance allowed for Meryra to still be bestowed with honor and praise.

In the immediately preceding scene, Akhenaten officially declares Meryra as the High Priest of Aten. Despite being the High Priest of Aten, Meryra was not recognized with the power to access the Aten, an exclusive ability of Akhenaten. In the text of this relief, Akhenaten addresses Meryra with the proclamation, "Behold, I am attaching you to myself, to be the Greatest of Seers of the Aten, in the House of Aten, in Ahket-aten."[4] In this statement, the reliance on Akhenaten in Atenism is referred to in a physical sense, as Akhenaten pledges to "attach" Meryra to him. This is similar to the contact the royal family has with the Aten, which is furnished with hands, or ankhs extending from its rays. One purpose of the ankhs is to literally fill the recipient through bodily orifices with the life and prosperity of the Aten.[1]

A variety of texts were found in the tomb, including prayers to be said by visitors to the tomb, as well as religious texts, such as the Hymn to the Aten. The Great Hymn to the Aten, traditionally ascribed to Akhenaten himself celebrates the Aten as the universal creator of all life. Although similar to hymns to Amun, the Hymn to the Aten reflects the originality of Akhenaten’s simplistic perception of his solar religion.[2]

See also

References

- Redford, Donald, B. "The Sun-disc in Akhenaten's Program: Its Worship and Antecedents, IJournal of the American Research Center in Egypt". 13. (1976), 47-61, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40001118. (accessed October 29, 2010).

- Kemp,Barry J.. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. New York: Routledge, 1989.

- Davies, Norman de Garis. The Rock Tombs of El Amarna. Part I. The Tomb of Meryre. London, Boston: Offices of the Egypt Exploration Fund, 1903. Facsimile in Internet Archive

- Murnane, William J., Meltzer, Edmund S,Texts from the Amarna period in Egypt. Scholars Press: 1995.