Amun

Amun (US: /ˈɑːmən/; also Amon, Ammon, Amen, Ancient Egyptian: jmn, reconstructed [jaˈmaːnuw]; Greek Ἄμμων Ámmōn, Ἅμμων Hámmōn) was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amaunet. With the 11th Dynasty (c. 21st century BC), Amun rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Montu.[1]

| Amun | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

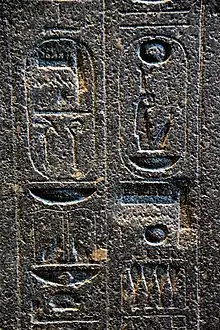

| Name in hieroglyphs | |||||

| Major cult center | Thebes | ||||

| Symbol | two vertical plumes, the ram-headed Sphinx (Criosphinx) | ||||

| Consort | |||||

| Offspring | Khonsu | ||||

| Greek equivalent | Zeus | ||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

After the rebellion of Thebes against the Hyksos and with the rule of Ahmose I (16th century BC), Amun acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra or Amun-Re.

Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the "Atenist heresy" under Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BC) held the position of transcendental, self-created[2] creator deity "par excellence"; he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety.[3] His position as King of Gods developed to the point of virtual monotheism where other gods became manifestations of him. With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.[3]

As the chief deity of the Egyptian Empire, Amun-Ra also came to be worshipped outside Egypt, according to the testimony of ancient Greek historiographers in Libya and Nubia. As Zeus Ammon, he came to be identified with Zeus in Greece.

Early history

_(2865505031).jpg.webp)

Amun and Amaunet are mentioned in the Old Egyptian Pyramid Texts.[4] The name Amun (written imn) meant something like "the hidden one" or "invisible".[5]

Amun rose to the position of tutelary deity of Thebes after the end of the First Intermediate Period, under the 11th Dynasty. As the patron of Thebes, his spouse was Mut. In Thebes, Amun as father, Mut as mother and the Moon god Khonsu formed a divine family or "Theban Triad".

Temple at Karnak

The history of Amun as the patron god of Thebes begins in the 20th century BC, with the construction of the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak under Senusret I. The city of Thebes does not appear to have been of great significance before the 11th Dynasty.

Major construction work in the Precinct of Amun-Re took place during the 18th Dynasty when Thebes became the capital of the unified ancient Egypt. Construction of the Hypostyle Hall may have also begun during the 18th Dynasty, though most building was undertaken under Seti I and Ramesses II. Merenptah commemorated his victories over the Sea Peoples on the walls of the Cachette Court, the start of the processional route to the Luxor Temple. This Great Inscription (which has now lost about a third of its content) shows the king's campaigns and eventual return with items of potential value and prisoners. Next to this inscription is the Victory Stela, which is largely a copy of the more famous Merneptah Stele found in the funerary complex of Merenptah on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes.[6] Merenptah's son Seti II added two small obelisks in front of the Second Pylon, and a triple bark-shrine to the north of the processional avenue in the same area. This was constructed of sandstone, with a chapel to Amun flanked by those of Mut and Khonsu.

The last major change to the Precinct of Amun-Re's layout was the addition of the first pylon and the massive enclosure walls that surrounded the whole Precinct, both constructed by Nectanebo I.

%252CN372.2.jpg.webp)

New Kingdom

Identification with Min and Ra

When the army of the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty expelled the Hyksos rulers from Egypt, the victor's city of origin, Thebes, became the most important city in Egypt, the capital of a new dynasty. The local patron deity of Thebes, Amun, therefore became nationally important. The pharaohs of that new dynasty attributed all of their successes to Amun, and they lavished much of their wealth and captured spoil on the construction of temples dedicated to Amun.[7]

The victory against the "foreign rulers" achieved by pharaohs who worshipped Amun caused him to be seen as a champion of the less fortunate, upholding the rights of justice for the poor.[3] By aiding those who traveled in his name, he became the Protector of the road. Since he upheld Ma'at (truth, justice, and goodness),[3] those who prayed to Amun were required first to demonstrate that they were worthy, by confessing their sins. Votive stelae from the artisans' village at Deir el-Medina record:

[Amun] who comes at the voice of the poor in distress, who gives breath to him who is wretched..You are Amun, the Lord of the silent, who comes at the voice of the poor; when I call to you in my distress You come and rescue me ... Though the servant was disposed to do evil, the Lord is disposed to forgive. The Lord of Thebes spends not a whole day in anger; His wrath passes in a moment; none remains. His breath comes back to us in mercy ... May your kꜣ be kind; may you forgive; It shall not happen again.[8]

Subsequently, when Egypt conquered Kush, they identified the chief deity of the Kushites as Amun. This Kush deity was depicted as ram-headed, more specifically a woolly ram with curved horns. Amun thus became associated with the ram arising from the aged appearance of the Kush ram deity, and depictions related to Amun sometimes had small ram's horns, known as the Horns of Ammon. A solar deity in the form of a ram can be traced to the pre-literate Kerma culture in Nubia, contemporary to the Old Kingdom of Egypt. The later (Meroitic period) name of Nubian Amun was Amani, attested in numerous personal names such as Tanwetamani, Arkamani, and Amanitore. Since rams were considered a symbol of virility, Amun also became thought of as a fertility deity, and so started to absorb the identity of Min, becoming Amun-Min. This association with virility led to Amun-Min gaining the epithet Kamutef, meaning "Bull of his mother",[9] in which form he was found depicted on the walls of Karnak, ithyphallic, and with a scourge, as Min was.

| Amun-Ra in hieroglyphs |

|---|

As the cult of Amun grew in importance, Amun became identified with the chief deity who was worshipped in other areas during that period, namely the sun god Ra. This identification led to another merger of identities, with Amun becoming Amun-Ra. In the Hymn to Amun-Ra he is described as

Lord of truth, father of the gods, maker of men, creator of all animals, Lord of things that are, creator of the staff of life.[10]

Atenist heresy

During the latter part of the eighteenth dynasty, the pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV) disliked the power of the temple of Amun and advanced the worship of the Aten, a deity whose power was manifested in the sun disk, both literally and symbolically. He defaced the symbols of many of the old deities, and based his religious practices upon the deity, the Aten. He moved his capital away from Thebes, but this abrupt change was very unpopular with the priests of Amun, who now found themselves without any of their former power. The religion of Egypt was inexorably tied to the leadership of the country, the pharaoh being the leader of both. The pharaoh was the highest priest in the temple of the capital, and the next lower level of religious leaders were important advisers to the pharaoh, many being administrators of the bureaucracy that ran the country.

The introduction of Atenism under Akhenaten constructed a monotheist worship of Aten in direct competition with that of Amun. Praises of Amun on stelae are strikingly similar in language to those later used, in particular, the Hymn to the Aten:

When thou crossest the sky, all faces behold thee, but when thou departest, thou are hidden from their faces ... When thou settest in the western mountain, then they sleep in the manner of death ... The fashioner of that which the soil produces, ... a mother of profit to gods and men; a patient craftsman, greatly wearying himself as their maker ... valiant herdsman, driving his cattle, their refuge and the making of their living ... The sole Lord, who reaches the end of the lands every day, as one who sees them that tread thereon ... Every land chatters at his rising every day, in order to praise him.[11]

When Akhenaten died, the priests of Amun-Ra reasserted themselves. Akhenaten's name was struck from Egyptian records, all of his religious and governmental changes were undone, and the capital was returned to Thebes. The return to the previous capital and its patron deity was accomplished so swiftly that it seemed this almost monotheistic cult and its governmental reforms had never existed. Worship of Aten ceased and worship of Amun-Ra was restored. The priests of Amun even persuaded his young son, Tutankhaten, whose name meant "the living image of Aten"—and who later would become pharaoh—to change his name to Tutankhamun, "the living image of Amun".

Theology

In the New Kingdom, Amun became successively identified with all other Egyptian deities, to the point of virtual monotheism (which was then attacked by means of the "counter-monotheism" of Atenism). Primarily, the god of wind Amun came to be identified with the solar god Ra and the god of fertility and creation Min, so that Amun-Ra had the main characteristic of a solar god, creator god and fertility god. He also adopted the aspect of the ram from the Nubian solar god, besides numerous other titles and aspects.

As Amun-Re, he was petitioned for mercy by those who believed suffering had come about as a result of their own or others' wrongdoing.

Amon-Re "who hears the prayer, who comes at the cry of the poor and distressed...Beware of him! Repeat him to son and daughter, to great and small; relate him to generations of generations who have not yet come into being; relate him to fishes in the deep, to birds in heaven; repeat him to him who does not know him and to him who knows him ... Though it may be that the servant is normal in doing wrong, yet the Lord is normal in being merciful. The Lord of Thebes does not spend an entire day angry. As for his anger – in the completion of a moment there is no remnant ... As thy Ka endures! thou wilt be merciful![12]

In the Leiden hymns, Amun, Ptah, and Re are regarded as a trinity who are distinct gods but with unity in plurality.[13] "The three gods are one yet the Egyptian elsewhere insists on the separate identity of each of the three."[14] This unity in plurality is expressed in one text:

All gods are three: Amun, Re and Ptah, whom none equals. He who hides his name as Amun, he appears to the face as Re, his body is Ptah.[15]

Henri Frankfort suggested that Amun was originally a wind god and pointed out that the implicit connection between the winds and mysteriousness was paralleled in a passage from the Gospel of John: "The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going."[John 3:8][16]

A Leiden hymn to Amun describes how he calms stormy seas for the troubled sailor:

The tempest moves aside for the sailor who remembers the name of Amon. The storm becomes a sweet breeze for he who invokes His name ... Amon is more effective than millions for he who places Him in his heart. Thanks to Him the single man becomes stronger than a crowd.[17]

Third Intermediate Period

Theban High Priests of Amun

While not regarded as a dynasty, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes were nevertheless of such power and influence that they were effectively the rulers of Egypt from 1080 to c. 943 BC. By the time Herihor was proclaimed as the first ruling High Priest of Amun in 1080 BC—in the 19th Year of Ramesses XI—the Amun priesthood exercised an effective hold on Egypt's economy. The Amun priests owned two-thirds of all the temple lands in Egypt and 90 percent of her ships and many other resources.[18] Consequently, the Amun priests were as powerful as the pharaoh, if not more so. One of the sons of the High Priest Pinedjem would eventually assume the throne and rule Egypt for almost half a decade as pharaoh Psusennes I, while the Theban High Priest Psusennes III would take the throne as king Psusennes II—the final ruler of the 21st Dynasty.

Decline

In the 10th century BC, the overwhelming dominance of Amun over all of Egypt gradually began to decline. In Thebes, however, his worship continued unabated, especially under the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, as Amun was by now seen as a national god in Nubia. The Temple of Amun, Jebel Barkal, founded during the New Kingdom, came to be the center of the religious ideology of the Kingdom of Kush. The Victory Stele of Piye at Gebel Barkal (8th century BC) now distinguishes between an "Amun of Napata" and an "Amun of Thebes". Tantamani (died 653 BC), the last pharaoh of the Nubian dynasty, still bore a theophoric name referring to Amun in the Nubian form Amani.

Iron Age and classical antiquity

Nubia and Sudan

In areas outside Egypt where the Egyptians had previously brought the cult of Amun his worship continued into classical antiquity. In Nubia, where his name was pronounced Amane or Amani, he remained a national deity, with his priests, at Meroe and Nobatia,[19] regulating the whole government of the country via an oracle, choosing the ruler, and directing military expeditions. According to Diodorus Siculus, these religious leaders were even able to compel kings to commit suicide, although this tradition stopped when Arkamane, in the 3rd century BC, slew them.[20]

In Sudan, excavation of an Amun temple at Dangeil began in 2000 under the directorship of Drs Salah Mohamed Ahmed and Julie R. Anderson of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan and the British Museum, UK, respectively. The temple was found to have been destroyed by fire and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) and C14 dating of the charred roof beams have placed the construction of the most recent incarnation of the temple in the 1st century AD. This date is further confirmed by the associated ceramics and inscriptions. Following its destruction, the temple gradually decayed and collapsed.[21]

Libya

In Libya there remained a solitary oracle of Amun in the Libyan Desert at the oasis of Siwa.[22] The worship of Ammon was introduced into Greece at an early period, probably through the medium of the Greek colony in Cyrene, which must have formed a connection with the great oracle of Ammon in the Oasis soon after its establishment. Iarbas, a mythological king of Libya, was also considered a son of Hammon. When Alexander the Great advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC, he was regarded as a liberator.[23] He was pronounced son of Amun at this oracle,[24] thus conquering Egypt without a fight. Henceforth, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father, and after his death, currency depicted him adorned with the Horns of Ammon as a symbol of his divinity.[25]

According to the 6th century author Corippus, a Libyan people known as the Laguatan carried an effigy of their god Gurzil, whom they believed to be the son of Ammon, into battle against the Byzantine Empire in the 540s AD.[26]

Levant

Amun is mentioned as a deity in the Hebrew Bible, and in the Nevi'im, texts presumably written in the 7th century BC, the name נא אמון No Amown occurs in reference to Thebes:[27]

The Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, said: "Behold, I am bringing punishment upon Amon of Thebes, and Pharaoh and Egypt and her gods and her kings, upon Pharaoh and those who trust in him."

Greece

.jpg.webp)

Amun, worshipped by the Greeks as Ammon, had a temple and a statue, the gift of Pindar (d. 443 BC), at Thebes,[28] and another at Sparta, the inhabitants of which, as Pausanias says,[29] consulted the oracle of Ammon in Libya from early times more than the other Greeks. At Aphytis, Chalcidice, Amun was worshipped, from the time of Lysander (d. 395 BC), as zealously as in Ammonium. Pindar the poet honored the god with a hymn. At Megalopolis the god was represented with the head of a ram (Paus. viii.32 § 1), and the Greeks of Cyrenaica dedicated at Delphi a chariot with a statue of Ammon.

Such was its reputation among the Classical Greeks that Alexander the Great journeyed there after the battle of Issus and during his occupation of Egypt, where he was declared "the son of Amun" by the oracle. Alexander thereafter considered himself divine. Even during this occupation, Amun, identified by these Greeks as a form of Zeus,[30] continued to be the principal local deity of Thebes.[7]

Several words derive from Amun via the Greek form, Ammon, such as ammonia and ammonite. The Romans called the ammonium chloride they collected from deposits near the Temple of Jupiter-Amun in ancient Libya sal ammoniacus (salt of Amun) because of proximity to the nearby temple.[31] Ammonia, as well as being the chemical, is a genus name in the foraminifera. Both these foraminiferans (shelled Protozoa) and ammonites (extinct shelled cephalopods) bear spiral shells resembling a ram's, and Ammon's, horns. The regions of the hippocampus in the brain are called the cornu ammonis – literally "Amun's Horns", due to the horned appearance of the dark and light bands of cellular layers.

In Paradise Lost, Milton identifies Ammon with the biblical Ham (Cham) and states that the gentiles called him the Libyan Jove.

See also

References

- Warburton (2012:211).

- Dick, Michael Brennan (1999). Born in heaven, made on earth: the making of the cult image in the ancient Near East. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 184. ISBN 1575060248.

- Arieh Tobin, Vincent (2003). Redford, Donald B. (ed.). Oxford Guide: The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology. Berkley Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-425-19096-X.

- "Die Altaegyptischen Pyramidentexte nach den Papierabdrucken und Photographien des Berliner Museums". 1908.

- Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-36116-3.

- Blyth, Elizabeth (2006). Karnak: Evolution of a Temple. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-0415404860.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911). "Ammon". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 860–861. This cites:

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911). "Ammon". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 860–861. This cites:

- Erman, Handbook of Egyptian Religion (London, 1907)

- Ed. Meyer, art. "Ammon" in Roscher's Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie

- Pietschmann, arts. "Ammon", "Ammoneion" in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie

- Works on Egyptian religion quoted (in the encyclopædia) under Egypt, section Religion

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1976). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-520-03615-8.

- Hart 2005, p. 21

- Budge, E.A. Wallis (1914). An Introduction to Egyptian Literature (1997 ed.). Minneola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 214. ISBN 0-486-29502-8..

- Wilson, John A. (1951). The Burden of Egypt (1963 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-226-90152-7.

- Wilson 300

- Morenz, Siegried (1992). Egyptian Religion. Translated by Ann E. Keep. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8014-8029-9.

- Frankfort, Henri; Wilson, John A.; Jacobsen, Thorkild (1960). Before Philosophy: The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0140201987.

- Assmann, Jan (2008). Of God and Gods. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-299-22554-4.

- Frankfort, Henri (1951). Before Philosophy. Penguin Books. p. 18. ASIN B0006EUMNK.

- Jacq, Christian (1999). The Living Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 143. ISBN 0-671-02219-9.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London, England: Thames & Hudson. p. 175. ISBN 978-0500286289.

- Herodotus, The Histories ii.29

- Griffith 1911.

- Sweek, Tracey; Anderson, Julie; Tanimoto, Satoko (2012). "Architectural Conservation of an Amun Temple in Sudan". Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. London, England: Ubiquity Press. 10 (2): 8–16. doi:10.5334/jcms.1021202.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece x.13 § 3

- Ring et al. 1994, pp. 49, 320

- Bosworth 1988, pp. 71–74.

- Dahmen 2007, pp. 10–11

- Mattingly, D.J. (1983). "The Laguatan: A Libyan Tribal Confederation in the Late Roman Empire" (PDF). Libyan Studies. London, England: Society for Libyan Studies. 14: 98–99. doi:10.1017/S0263718900007810.

- "Strong's Concordance / Gesenius' Lexicon". Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. ix.16 § 1.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. iii.18 § 2.

- Jeremiah. xlvi.25. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Eponyms". h2g2. BBC Online. 11 January 2003. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

Sources

- David Klotz, Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple (New Haven, 2006)

- David Warburton, Architecture, Power, and Religion: Hatshepsut, Amun and Karnak in Context, 2012, ISBN 9783643902351.

- E. A. W. Budge, Tutankhamen: Amenism, Atenism, and Egyptian Monotheism (1923).

Further reading

- Assmann, Jan (1995). Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism. Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0710304650.

- Ayad, Mariam F. (2009). God's Wife, God's Servant: The God's Wife of Amun (c. 740–525 BC). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415411707.

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene (1994). "The Khonsu Cosmogony". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 31: 169–189. doi:10.2307/40000676. JSTOR 40000676.

- Gabolde, Luc (2018). Karnak, Amon-Rê : La genèse d'un temple, la naissance d'un dieu (in French). Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. ISBN 978-2-7247-0686-4.

- Guermeur, Ivan (2005). Les cultes d'Amon hors de Thèbes: Recherches de géographie religieuse (in French). Brepols. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

- Klotz, David (2012). Caesar in the City of Amun: Egyptian Temple Construction and Theology in Roman Thebes. Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. ISBN 978-2-503-54515-8.

- Kuhlmann, Klaus P. (1988). Das Ammoneion. Archäologie, Geschichte und Kultpraxis des Orakels von Siwa (in German). Verlag Phillip von Zabern in Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3805308199.

- Otto, Eberhard (1968). Egyptian art and the cults of Osiris and Amon. Abrams.

- Roucheleau, Caroline Michelle (2008). Amun temples in Nubia: a typological study of New Kingdom, Napatan and Meroitic temples. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407303376.

- Thiers, Christophe, ed. (2009). Documents de théologies thébaines tardives. Université Paul-Valéry.

- Zandee, Jan (1948). De Hymnen aan Amon van papyrus Leiden I. 350 (in Dutch). E.J. Brill.

- Zandee, Jan (1992). Der Amunhymnus des Papyrus Leiden I 344, Verso (in German). Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amun. |

- Wim van den Dungen, Leiden Hymns to Amun

- (in Spanish) Karnak 3D :: Detailed 3D-reconstruction of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak, Marc Mateos, 2007

- Amun with features of Tutankhamun (statue, c. 1332–1292 BC, Penn Museum)