Rock-cut architecture

Rock-cut architecture is the creation of structures, buildings, and sculptures by excavating solid rock where it naturally occurs. Rock-cut architecture is designed and made by man from the start to finish. In India and China, the terms cave and cavern are often applied to this form of man-made architecture. However, caves and caverns that began in natural form are not considered to be rock-cut architecture even if extensively modified.[1] Although rock-cut structures differ from traditionally built structures in many ways, many rock-cut structures are made to replicate the facade or interior of traditional architectural forms. Interiors were usually carved out by starting at the roof of the planned space and then working downward. This technique prevents stones falling on workers below. The three main uses of rock-cut architecture were temples (like those in India), tombs (like those in Petra, Jordan) and cave dwellings (like those in Cappadocia, Turkey).

Some rock-cut architecture, mostly for tombs, is excavated entirely in chambers under the surface of relatively level rock. If the excavation is instead made into the side of a cliff or steep slope, there can be an impressive facade, as found in Lycian tombs, Petra, Ajanta and elsewhere. The most laborious and impressive rock-cut architecture is the excavation of tall free-standing monolithic structures entirely below the surface level of the surrounding rock, in a large excavated hole around the structure. Ellora in India and Lalibela in Ethiopia (built by the Zagwe dynasty) provide the most spectacular and famous examples of such structures.

Rock-cut architecture, though intensely laborious with ancient tools and methods, was presumably combined with quarrying the rock for use elsewhere; the huge amounts of stone removed have normally vanished from the site. It is also said to be cut, hewn, etc., "from the living rock".[2] Another term sometimes associated with rock-cut architecture is monolithic architecture, which is rather applied to free-standing structures made of a single piece of material. Monolithic architecture is often rock-cut architecture (e.g. Ellora Kailasanathar Temple), but monolithic structures might be also cast of artificial material, e.g. concrete.

The Gommateshwara statue (Bahubali), the largest monolithic statue in the world, at Shravanabelagola, Karnataka, India, was built in 983 CE and was carved from a large single block of granite.[3][4] In many parts of the world there are also rock reliefs, relief sculptures carved into rock faces, outside caves or at other sites.

History

Ancient monuments of rock-cut architecture are widespread in several regions of world. A small number of Neolithic tombs in Europe, such as the c. 3,000 B.C. Dwarfie Stane on the Orkney island of Hoy, were cut directly from the rock, rather than constructed from stone blocks.

Alteration of naturally formed caverns, although distinct from completely carved structures in the strict sense, date back to the neolithic period on several Mediterranean islands e.g. Malta (Hypogeum of Ħal-Saflieni), Sardinia (Anghelu Ruju, built between 3,000 and 1,500 BCE) and others.

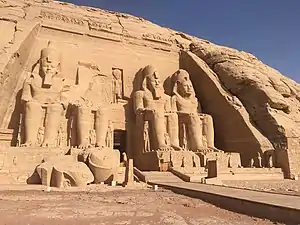

During the Bronze age, Nubian ancestors of the Kingdom of Kush built speos between 3700 to 3250 BCE. This greatly influenced the architecture of the New kingdom.[5] Large-scale rock-cut structures were built in Ancient Egypt. Among these monuments was the Great Temple of Ramesses II, known as Abu Simbel, located along the Nile in Nubia, near the borders of Sudan about 300 kilometers from Aswan in Egypt. It dates from about the 19th Dynasty (ca. 1280 BCE), and consists of a monumentally scaled facade carved out of the cliff and a set of interior chambers that form its sanctuary.[6]

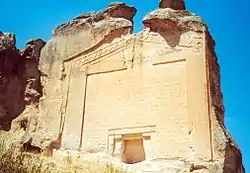

In the 8th century, the Phrygians started some of the earliest rock-cut monuments, such as the Midas monument (700 BCE), dedicated to the famous Phrygian king Midas.[7][8]

In the 5th century BCE, the Lycians, who inhabited southern Anatolia (now Turkey) built hundreds of rock-cut tombs of a similar type, but smaller in scale.[9] Excellent examples are to be found near Dalyan, a town in Muğla Province, along the sheer cliffs that faces a river. Since these served as tombs rather than as religious sites, the interiors were usually small and unassuming. The ancient Etruscans of central Italy also left an important legacy of rock-cut architecture, mostly tombs, as those near the cities of Tarquinia and Vulci.

The creation of rock-cut tombs in ancient Israel began in the 8th-century BCE and continued through the Byzantine period. The Tomb of Absalom was constructed in the 1st century CE in the Kidron Valley of Jerusalem.

Rock-cut architecture occupies a particularly important place in the history of Indian Architecture. The earliest instances of Indian rock-cut architecture, the Barabar caves, date from about the 3rd to the 2nd century BCE. They were built by the Buddhist monks and consisted mostly of multi-storey buildings carved into the mountain face to contain living and sleeping quarters, kitchens, and monastic spaces.[10] Some of these monastic caves had shrines in them to the Buddha, bodhisattvas and saints.[11] As time progressed, the interiors became more elaborate and systematized; surfaces were often decorated with paintings, such as those at Ajanta. At the beginning of the 7th century Hindu rock-cut temples began to be constructed at Ellora. Unlike most previous examples of rock-cut architecture which consisted of a facade plus an interior, these temples were complete three-dimensional buildings created by carving away the hillside. They required several generations of planning and coordination to complete. Other major examples of rock-cut architecture in India are at Ajanta and Pataleshwar.

.jpg.webp)

The Nabataeans in their city of Petra, now in Jordan, extended the Western Asian tradition, carving their temples and tombs into the yellowish-orange rock that defines the canyons and gullies of the region. These structures, dating from 1st century BCE to about 2nd century CE, are particularly important in the history of architecture given their experimental forms.[12] Here too, because the structures served as tombs, the interiors were rather perfunctory. In Petra one even finds a theater where the seats are cut out of the rock.

The technological skills associated with making these complex structures moved into China along the trade routes. The Longmen Grottoes, the Mogao Caves, and the Yungang Grottoes consist of hundreds of caves many with statues of Buddha in them. Most were built between 460–525 CE. There are extensive rock-cut buildings, including houses and churches in Cappadocia, Turkey.[13] They were built over a span of hundreds of years prior to the 5th century CE. Emphasis here was more on the interiors than the exteriors.

Another extensive site of rock-cut architecture is in Lalibela, a town in northern Ethiopia. The area contains numerous Orthodox churches in three dimensions, as at Ellora, that were carved out of the rock. These structures, which date from the 12th and 13th centuries CE and which are the last significant examples of this architectural form, ranks as among the most magnificent examples of rock-cut architecture in the world, with both interior and exterior brought to fruition.

Art

Ancient rock cut tombs, temples and monasteries often have been adorned with frescoes and reliefs. The high resistance of natural cliff, skilled use of plaster and constant microclimate often have helped to preserve this art in better condition than in conventional buildings. Such exceptional examples are the ancient and early medieval frescoes in such locations as Bamyan Caves in Afghanistan with the most ancient known oil paintings in the world from 8th century CE, Ajanta Caves in India with well preserved tempera paintings from 2nd century BCE, Christian frescoes on Churches of Göreme, Turkey and numerous other monuments in Asia, Europe and Africa.

Chronology

- Egyptian rock-cut tombs (1450 BCE, Thebes, Egypt).[7]

- Hittite rock-cut sanctuaries (1250 BCE).[7]

- Phrygian rock-cut tombs such as the Midas monument (700 BCE).[7][8]

- Etruscan rock-cut tombs, Etruria, Italy (500 BCE).[7]

- Tomb of Darius I (Naqsh-e Rostam (480 BCE).[7]

- Lycian rock-cut tombs (4th century BCE).[7]

- Barabar caves, India (250 BCE).[7]

- Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, India (2nd century BCE).

- Buddhist caves, Western Ghats, India (100 BCE).[7]

- Petra, Jordan (100 CE).[7]

- Buddhist caves, Northwestern India (100 CE).[7]

- Houses, Tiermes, Spain (100 CE)

- Buddhist caves, Dunhuang, China (400 CE).[7]

- Buddhist caves, Ajanta, India (480 CE).[7]

- Hindu temple, Elephanta, India (600 CE).[7]

- Hindu temple, Southern India (650–750 CE).[7]

- Hindu, Buddhist and Jain caves, Ellora, India (700–900 CE).[7]

- Churches, Cappadoccia, Turkey (900 CE).[7]

- Churches, Lalibela, Ethiopia (1000 CE).[7]

See also

- Rock-cut architecture of Cappadocia

- Monolithic church

- Dugout (shelter) – Hole or depression used as shelter

- Yaodong

- List of cave monasteries

- Ostrog Monastery – Monastery of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegro

- Degua Tembien, Ethiopia

- Thamud – Ancient Arab tribe mentioned in the Quran

- List of archaeological sites by country

- List of colossal sculpture in situ

- List of largest monoliths

- Indian rock-cut architecture

- List of rock-cut temples in India

- Rock-cut tomb

- Naqsh-e Rustam

- Kandovan, Osku

- Underground construction

References

- Francis Ching, Mark Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture (Wiley, 2006)

- Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged, under "living".

- Statue of Gomateswara

- World's biggest monolithic Statue

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- Aidan Dodson. Egyptian Rock-Cut Tombs. Shire Publications 1999.

- Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118007396.

- Roller, Lynn E. (1999). In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. University of California Press. pp. 84–110. ISBN 9780520919686.

- Lycian tombs

- S. Nagaraju Buddhist Architecture of Western India, c. 250 BC – AD 300 (Agam Kala Prakashan, 1981)

- Vidya Dehejia, Early Buddhist Rock Temples; a Chronology. (Cornell University Press, 1972)

- Rababeh, Shaher M. Rababeh, ’’How Petra was Built: an Analysis of the Construction Techniques of the Nabataean Freestanding Buildings and Rock-cut Monuments in Petra, Jordan (Oxford, England: Archaeopress), 2005.

- Spiro Kostof, Caves of God: the Monastic Environment of Byzantine Cappadocia (MIT Press, 1972). Vidya Dehejia, (Cornell University Press, 1972)

- Burgess, James and Fergusson J. Cave Temples of India. (London: W.H. Allen & Co., 1880. Delhi: Munshiram Manohar Lal Publishers Pvt Ltd., Delhi, 2005).