Tomb of the Virgin Mary

Church of the Sepulchre of Saint Mary, also Tomb of the Virgin Mary (Hebrew: קבר מרים; Greek: Τάφος της Παναγίας), is a Christian tomb in the Kidron Valley – at the foot of Mount of Olives, in Jerusalem – believed by Eastern Christians to be the burial place of Mary, the mother of Jesus.[1] The Status Quo, a 250-year old understanding between religious communities, applies to the site.[2][3]

History

The Sacred Tradition of Eastern Christianity teaches that the Virgin Mary died a natural death (the Dormition of the Theotokos, the falling asleep), like any human being; that her soul was received by Christ upon death; and that her body was resurrected on the third day after her repose, at which time she was taken up, soul and body, into heaven in anticipation of the general resurrection. Her tomb, according to this teaching, was found empty on the third day.

Roman Catholic teaching holds that Mary was "assumed" into heaven in bodily form, the Assumption; the question of whether or not Mary actually underwent physical death remains open in the Catholic view. On 25 June 1997 Pope John Paul II said that Mary experienced natural death prior to her assumption into Heaven.[4]

A narrative known as the Euthymiaca Historia (written probably by Cyril of Scythopolis in the 5th century) relates how the Emperor Marcian and his wife, Pulcheria, requested the relics of the Virgin Mary from Juvenal, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, while he was attending the Council of Chalcedon (451). According to the account, Juvenal replied that, on the third day after her burial, Mary's tomb was discovered to be empty, only her shroud being preserved in the church of Gethsemane. In 452 the shroud was sent to Constantinople, where it was kept in the Church of Our Lady of Blachernae (Panagia Blacherniotissa).[5]

According to other traditions, it was the Cincture of the Virgin Mary which was left behind in the tomb,[6] or dropped by her during Assumption.

Archaeology

In 1972, Bellarmino Bagatti, a Franciscan friar and archaeologist, excavated the site and found evidence of an ancient cemetery dating to the 1st century; his findings have not yet been subject to peer review by the wider archaeological community, and the validity of his dating has not been fully assessed.

Bagatti interpreted the remains to indicate that the cemetery's initial structure consisted of three chambers (the actual tomb being the inner chamber of the whole complex), was adjudged in accordance with the customs of that period. Later, the tomb interpreted by the local Christians to be that of Mary's was isolated from the rest of the necropolis, by cutting the surrounding rock face away from it. An edicule was built on the tomb.[7]

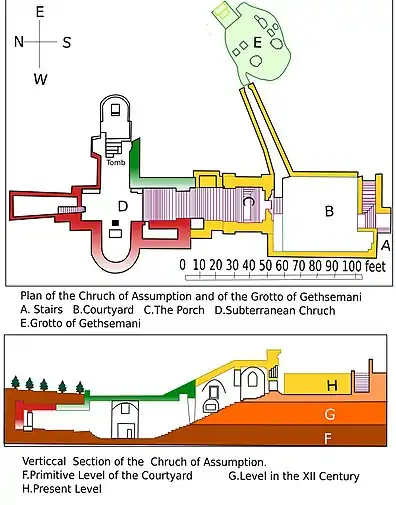

A small upper church on an octagonal footing was built by Patriarch Juvenal (during Marcian's rule) over the location in the 5th century; this was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 614. During the following centuries the church was destroyed and rebuilt many times, but the crypt was left untouched, as for Muslims it is the burial place of the mother of prophet Isa (Jesus). It was rebuilt then in 1130 by the Crusaders, who installed a walled Benedictine monastery, the Abbey of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehoshaphat; the church is sometimes mentioned as the Shrine of Our Lady of Josaphat. The monastic complex included early Gothic columns, red-on-green frescoes, and three towers for protection. The staircase and entrance were also part of the Crusaders' church. This church was destroyed by Saladin in 1187, but the crypt was still respected; all that was left was the south entrance and staircase, the masonry of the upper church being used to build the walls of Jerusalem. In the second half of the 14th century Franciscan friars rebuilt the church once more. The Greek Orthodox clergy launched a Palm Sunday takeover of various Holy Land sites, including this one, in 1757 and expelled the Franciscans.[8] The Ottomans supported this "status quo" in the courts.[9] Since then, the tomb has been owned by the Greek Orthodox Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church of Jerusalem, while the grotto of Gethsemane remained in the possession of the Franciscans.

The church

Preceded by a walled courtyard to the south, the cruciform church shielding the tomb has been excavated in a rock-cut cave[10] entered by a wide descending stair dating from the 12th century. On the right side of the staircase (towards the east) there is the chapel of Mary's parents, Joachim and Anne, initially built to hold the tomb of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, the daughter of Baldwin II, whose sarcophagus has been removed from there by the Greek Orthodox. On the left (towards the west) there is the chapel of Saint Joseph, Mary's husband, initially built as the tomb of two other female relatives of Baldwin II.[11]

On the eastern side of the church there is the chapel of Mary's tomb. Altars of the Greeks and Armenians also own the east apse. A niche south of the tomb is a mihrab indicating the direction of Mecca, installed when Muslims had joint rights to the church. Currently the Muslims have no more ownership rights to this site. On the western side there is a Syriac altar.

The Armenian Patriarchate Armenian Apostolic Church of Jerusalem and Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem are in possession of the shrine. The Syriacs, the Copts, and the Ethiopians have minor rights.

Authenticity

A legend, which was first mentioned by Epiphanius of Salamis in the 4th century AD, purported that Mary may have spent the last years of her life in Ephesus, Turkey. The Ephesians derived it from John's presence in the city, and Jesus’ instructions to John to take care of Mary after his death. Epiphanius, however, pointed out that although the Bible mentions John leaving for Asia, it makes no mention of Mary going with him.[12] The Eastern Orthodox Church tradition believes that Virgin Mary lived in the vicinity of Ephesus, at Selçuk, where there is a place currently known as the House of the Virgin Mary and venerated by Catholics and Muslims, but argues that she only stayed there for a few years, even though there are accounts of her spending nine years until her death.

Although no information about the end of Mary's life or her burial are provided in the New Testament accounts, and many Christians believe that none exist in early apocrypha, some apocryphon are offered as supporting Mary's death (or other final fate). The Book of John about the Dormition of Mary, written in either the 1st, 3rd, 4th, or 7th century,[13][14] places her tomb in Gethsemene, as does the 4th century Treatise about the passing of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[14]

The pilgrim Antoninus of Piacenza, writing of travels in 560-570 CE, mentions in that valley was "the basilica of the Blessed Mary, which they say was her house; in which is shown a sepulchre, from which they say that the Blessed Mary was taken up into heaven."[15] Later, Saints Epiphanius of Salamis, Gregory of Tours, Isidore of Seville, Modest, Sophronius of Jerusalem, German of Constantinople, Andrew of Crete, and John of Damascus talk about the tomb being in Jerusalem, and bear witness that this tradition was accepted by all the Churches of East and West.

Other claims

Turkmen Keraites believe, according to a Nestorian tradition that another tomb of the Virgin Mary is located in Mary, Turkmenistan a town originally named Mari.

Other claims are that Jesus, after surviving the crucifixion, travelled to India along with the Virgin Mary where they remained until the end of their lives.[16] The Ahmadiyya movement believe that Mary was buried in the town of Murree, Pakistan and her tomb is presently located in the shrine Mai Mari da Ashtan. The authenticity of these claims is not yet academically established and has not undergone any scholastic or academic research, nor canonical endorsement from the Holy See, nor anyone else.[17]

Another tradition exists among the Christians of Nineveh in northern Iraq, that the tomb of Mary is located near Erbil, linking the site to the direction of tilt of the former Great Mosque of al-Nuri minaret in Mosul.[18]

Staircase of 47 steps leading from the entrance down into crypt with the tomb

Staircase of 47 steps leading from the entrance down into crypt with the tomb The entrance stairs, lower part

The entrance stairs, lower part The Chapel of Saints Joachim and Anne, originally the tomb of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem

The Chapel of Saints Joachim and Anne, originally the tomb of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem Icons in the Chapel of Saints Joachim and Anne

Icons in the Chapel of Saints Joachim and Anne The Tomb of Mary: facade covered in icons and entrance door

The Tomb of Mary: facade covered in icons and entrance door The Tomb of Mary: facade covered in icons and entrance door

The Tomb of Mary: facade covered in icons and entrance door Inside the Tomb of Mary: the stone bench on which the Virgin's body was laid out

Inside the Tomb of Mary: the stone bench on which the Virgin's body was laid out Crypt, western apse: icon of Mary and Christ

Crypt, western apse: icon of Mary and Christ Icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos

Icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos

See also

- Abbey of Saint Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat

- Dormition of the Theotokos (Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Catholic theologies)

- Assumption of Mary (the same event differently seen by the Roman Catholic theology)

- House of the Virgin Mary, Catholic shrine on Mt. Koressos, Turkey

References

- What's A Mother To Do? at AmericanCatholic.org

- UN Conciliation Commission (1949). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine Working Paper on the Holy Places.

- Cust, 1929, The Status Quo in the Holy Places

- Pope John Paul II General audience, Wednesday, 25 June 1997

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Tomb of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Serfes, Father Demetrios (1 March 1999), Belt of the Holy Theotokos, archived from the original on 31 January 2010, retrieved 16 January 2010

- Alviero Niccacci, "Archaeology, New Testament, and Early Christianity" Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Faculty of Biblical Sciences and Archaeology of the Pontifical University Antonianum in Rome

- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre:A Work in Progress

- Tomb of Mary

- See Rock cut architecture.

- Murphy-O'Connor, 2008, p. 149

- Vasiliki Limberis, 'The Council of Ephesos: The Demise of the See of Ephesos and the Rise of the Cult of the Theotokos' in Helmut Koester, Ephesos: Metropolis of Asia (2004), 327.

- Roberts, 1886, p. 587: "In two MMS. the author is said to be James the Lord's brother; in one, John Archbishop of Thessalonica, who lived in the seventh century."

- Herbermann, 1901, p. 774: "the 'Joannis liber de Dormitione Marie' (third to fourth century), and the treatise 'De transitu B.M. Virginis' (fourth century) place her tomb at Gethsemane"

- Antoninus of Piacenza, 1890, p. 14

- Jesus in Kashmir, The Lost Tomb-pp 163-182-Suzanne Olsson (2019)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2014-08-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Geary, 1878, p. 88

Bibliography

- Adomnán (1895). Pilgrimage of Arculfus in the Holy Land (about the year A.D. 670). Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. (about Arculf, p. 17)

- Antoninus of Piacenza (1890). Of the Holy Places Visited by Antoninus Martyr About the year A.D. 570. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1899). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. 1. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 20-21)

- Cust, L.G.A. (1929). The Status Quo in the Holy Places. H.M.S.O. for the High Commissioner of the Government of Palestine.

- Olsson, Suzanne, Jesus in Kashmir The Lost Tomb (2019) www.rozabal.com|Investigation in to the alleged final resting place of Mary in Mari Ashtan, Pakistan, with photos and additional resource links.

- Fabri, F. (1896). Felix Fabri (circa 1480–1483 A.D.) vol I, part II. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. (pp. 464-469)

- Geary, Grattan (1878). Through Asiatic Turkey: narrative of a journey from Bombay to the Bosphorus. 2. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

- Herbermann, C.G. (1901). Catholic Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia Press.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. OCLC 1004386. (pp. 210, 219)

- Maundrell, H. (1703). A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: At Easter, A. D. 1697. Oxford: Printed at the Theatre. (p. 102)

- Moudjir ed-dyn (1876). Sauvaire (ed.). Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn. (pp. 27, 33, 193)

- Murphy-O'Connor, J. (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Phokas, J. (1889). The Pilgrimage of Johannes Phocas in the Holy Land. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. (pp. 20-21)

- Pringle, Denys (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The city of Jerusalem. III. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39038-5. (pp. 287-306)

- Roberts, A. (1886). The Ante-Nicene Fathers: The twelve patriarchs, Excerpts and epistles, The Clementina, Apocrypha, Decretals, Memoirs of Edessa and Syriac documents, Remains of the first ages: Volume 8 of The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325. C. Scribner's Sons.

- Vogüé, de, M. (1860). Les églises de la Terre Sainte.(pp. 305 - 313)

- Warren, C.; Conder, C.R. (1884). The Survey of Western Palestine: Jerusalem. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 40, 402)

External links

- Tomb of the Virgin Mary at Sacred Destinations provides a description of the interior and history of the site.

- Jerusalem Mary`s Tomb at http://allaboutjerusalem.com

- Assumptions About Mary (comments on the historicity of the site) at Catholic Answers.

- O Svetoj zemlji, Jerusalimu i Sinaju at http://www.svetazemlja.info

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Tomb of the Blessed Virgin Mary". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Tomb of the Blessed Virgin Mary". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.