Mihrab

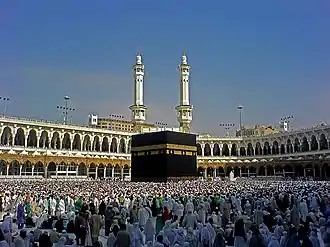

Mihrab (Arabic: محراب, miḥrāb, pl. محاريب maḥārīb), (Persian: مهرابه, mihrāba), is a semicircular niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, that is, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and hence the direction that Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall".

.jpg.webp)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

The minbar, which is the raised platform from which an imam (leader of prayer) addresses the congregation, is located to the right of the mihrab.

Etymology

The word is possibly derived from the verb ḥariba ("to fight", from the root Ḥ-R-B), so miḥrāb would mean "battlefield" or "place of fight (with Satan)". Some scholars have suggested that the word is from the Ethiopian mekʷerab, or from the Hebrew ḥorḇôt.[1]

History

The word mihrab originally had a non-religious meaning and simply denoted a special room in a house; a throne room in a palace, for example. The Fath al-Bari (p. 458), on the authority of others, suggests the mihrab is "the most honorable location of kings" and "the master of locations, the front and the most honorable." The Mosques in Islam (p. 13), in addition to Arabic sources, cites Theodor Nöldeke and others as having considered a mihrab to have originally signified a throne room.

The term was subsequently used by the Islamic prophet Muhammad to denote his own private prayer room. The room additionally provided access to the adjacent mosque, and the Prophet would enter the mosque through this room. This original meaning of mihrab – i.e. as a special room in the house – continues to be preserved in some forms of Judaism where mihrabs are rooms used for private worship. In the Qur'an, the word mihrab refers to a sanctuary/place of worship. The passage "then he [i.e. Zechariah] came forth to his people from the sanctuary/place of worship"[29:11], for example, is inscribed on or over some mihrabs.[2]

During the reign of Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656), the Caliph ordered a sign to be posted on the wall of the mosque at Medina so that pilgrims could easily identify the direction in which to address their prayers (i.e. that of Mecca). The sign was however just a sign on the wall, and the wall itself remained flat. Subsequently, during the reign of Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik (Al-Walid I, r. 705–715), Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (Mosque of the Prophet) was renovated and the governor (wāli) of Medina, Umar ibn AbdulAziz, ordered that a niche be made to designate the qibla wall (which identifies the direction of Mecca), and it was in this niche that Uthman's sign was placed.

Eventually, the niche came to be universally understood to identify the qibla wall, and so came to be adopted as a feature in other mosques. A sign was no longer necessary.

Architecture

Mihrabs are a relevant part of Islamic culture and mosques. Since they are used to indicate the direction for prayer, they serve as an important focal point in the mosque. They are usually decorated with ornamental detail that can be geometric designs, linear patterns, or calligraphy. This ornamentation also serves a religious purpose. The calligraphy decoration on the mihrabs are usually from the Qur'an and are devotions to God so that God's word reaches the people.[3] Common designs amongst mihrabs are geometric foliage that are close together so that there is no empty space in-between the art.[3]

Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba: The mihrab in the Mosque of Cordoba is a highly decorated piece of art that draws one's attention. It is a contribution made by Al-Hakam II that is not just used for prayer.[4] It is used as a place of convergence in the mosque, where visitors could be amazed by its beauty and gilded designs. The entrance is covered in mosaics "which links to the Byzantium tradition, produced by the craftsmen sent by Emperor Nicephorus II. These mosaics extend along the voussoirs with a geometric and plant-based design, but also in the inscriptions which record verses from the Koran".[4] This mihrab is also a bit different from a normal mihrab due to its scale. It takes up a whole room instead of just a niche.[5] This style of mihrab set a standard for other mihrab construction in the region.[6] The use of the horseshoe arch, carved stucco, and glass mosaics made an impression for the aesthetic of mihrabs, "although no other extant mihrab in Spain or western North Africa is as elaborate."[6]

The Great Mosque of Damascus: The Great Mosque of Damascus was started by al-Walid in 706.[7] It was built as a hypostyle mosque, built with a prayer hall leading to the mihrab, "on the back wall of the sanctuary are four mihrabs, two of which are the mihrab of the Companions of the Prophet in the eastern half and the great mihrab at the end of the transept".[7] The mihrab is decorated similarly to the rest of the mosque in golden vines and vegetal imagery. The lamp hanging in the mihrab has been theorized as the motif of a pearl, due to the indications that dome of the mihrab has scalloped edges.[8] There have been other mosques that have mihrabs similar to this that follow the same theme, with scalloped domes that are "concave like a conch or mother of pearl shell.[8]

Present-day use

Today, mihrabs vary in size, are usually ornately decorated and often designed to give the impression of an arched doorway or a passage to Mecca.

In exceptional cases, the mihrab does not follow the qibla direction. One example is the Mezquita of Córdoba, Spain that points northeast by east instead of southeast. Among the proposed explanations, there is the localization of the ancient Roman cardo street besides the old temple the Mezquita was built upon.

Another is the Masjid al-Qiblatayn, or the Mosque of the Two Qiblas. This is where the Prophet Muhammad received the command to change the direction of prayer from Jerusalem to Mecca, thus has two prayer niches. In the 21st century the mosque was renovated, and the old prayer niche facing Jerusalem was removed, and the one facing Mecca was left.

Gallery

- Mihrabs

A mihrab in Sultan Ibrahim Mosque in Rethymno

A mihrab in Sultan Ibrahim Mosque in Rethymno Mihrab in the Great Mosque of Damascus

Mihrab in the Great Mosque of Damascus_MET_DP235035.jpg.webp) Mihrab (prayer niche); 1354–1355; mosaic of polychrome-glazed cut tiles on stonepaste body, set into mortar; 343.1 x 288.7 cm, weight: 2041.2 kg; from Isfahan (Iran); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mihrab (prayer niche); 1354–1355; mosaic of polychrome-glazed cut tiles on stonepaste body, set into mortar; 343.1 x 288.7 cm, weight: 2041.2 kg; from Isfahan (Iran); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Mihrab in the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan; this mihrab dates in its present state from the 9th century, Kairouan, Tunisia

Mihrab in the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan; this mihrab dates in its present state from the 9th century, Kairouan, Tunisia

-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Chain_(Mihrab).jpg.webp) Mihrab in the Dome of the Chain, Temple Mount, Jerusalem.

Mihrab in the Dome of the Chain, Temple Mount, Jerusalem.

Mihrab in the Qila-i-Kuhna Mosque, in Delhi

Mihrab in the Qila-i-Kuhna Mosque, in Delhi Mihrab in the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, in Roxbury, Boston.

Mihrab in the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, in Roxbury, Boston.

References

- Fehérvári 1993, p. 7

- Kuban, Doğan (1974), The Mosque and Its Early Development, Muslim Religious Architecture, Leiden: Brill, p. 3, ISBN 90-04-03813-2.

- Terasaki, Steffie. "Mihrab". courses.washington.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "Mihrab". Mihrab. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "Mezquita de Córdoba | The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century". Archnet. p. 83. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Sheila S., Blair (2009). Bloom, Jonathan M; Blair, Sheila S (eds.). "The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195309911.001.0001. ISBN 9780195309911. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Grafman, Rafi; Rosen-Ayalon, Myriam (1999). "The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus". Muqarnas. 16: 8. JSTOR 1523262.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2001). The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Ummayyad Visual Culture. BRILL. ISBN 9789004116382.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mihrabs. |

- Diez, Ernst (1936), "Mihrāb", Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3, Leiden: Brill, pp. 559–565.

- Fehérvári, Geza (1993), "Mihrāb", Encyclopaedia of Islam, New edition, 7, Leiden: Brill, pp. 7–15.