Trench railways

Trench railways represented military adaptation of early 20th century railway technology to the problem of keeping soldiers supplied during the static trench warfare phase of World War I. The large concentrations of soldiers and artillery at the front lines required delivery of enormous quantities of food, ammunition and fortification construction materials where transport facilities had been destroyed. Reconstruction of conventional roads (at that time rarely surfaced) and railways was too slow, and fixed facilities were attractive targets for enemy artillery. Trench railways linked the front with standard gauge railway facilities beyond the range of enemy artillery.[1] Empty cars often carried litters returning wounded from the front.

Overview

France had developed portable Decauville railways for agricultural areas, small scale mining and temporary construction projects. France had standardized 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) narrow gauge Decauville military equipment and Germany adopted similar feldbahn of the same gauge. British War Department Light Railways and the United States Army Transportation Corps used the French 600 mm narrow gauge system. Russia used Decauville 600 mm narrow gauge and 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in) narrow gauge systems.

Unskilled labourers and soldiers could quickly assemble prefabricated 5-meter (16 ft 5 in) sections of track weighing about 100 kilograms (220 lb) along roads or over smooth terrain. The track distributed heavy loads to minimize development of muddy ruts through unpaved surfaces. Small locomotives pulled short trains of 10-tonne (22,000 lb) capacity cars through areas of minimum clearance and small-radius curves. Derailments were common, but the light rolling stock was relatively easy to rerail.[2] Steam locomotives typically carried a short length of flexible pipe (called a water-lifter) to refill water tanks from flooded shell holes.

Steam locomotives produced smoke that revealed their location to enemy artillery and aircraft. They required fog or darkness to operate within visual range of the front.[2] Daylight transport usually required animal power until internal combustion locomotives were developed. Large quantities of hay and grain were carried to the front as horses in warfare remained essential to logistics. Fodder for horses constituted the single biggest commodity exported from Britain to France during the war.

BL 9.2 inch Howitzer with shells lined up on the ground recently delivered from the trench railway in the foreground.

BL 9.2 inch Howitzer with shells lined up on the ground recently delivered from the trench railway in the foreground. Australian 17th Light Railway Operating Company ballast train near Ypres pulled by Cooke 2-6-2 tank locomotive # 1217.

Australian 17th Light Railway Operating Company ballast train near Ypres pulled by Cooke 2-6-2 tank locomotive # 1217. 5th Australian Field Ambulance Company soldiers evacuating wounded from the front near Ypres in trench railway hand cars.

5th Australian Field Ambulance Company soldiers evacuating wounded from the front near Ypres in trench railway hand cars.

French equipment

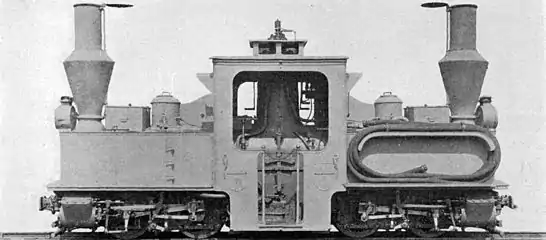

French equipment was largely designed on the initiative of Artillery Captain Prosper Péchot beginning in 1888. The 10-tonne (9.8-long-ton; 11-short-ton) Fairlie articulated 0-4-4-0T Péchot-Bourdon locomotive was named for him and engineer Bourdon of the 5th engineer regiment (5e régiment du génie) in Toul. Prior to outbreak of war 150 km (93 mi) of military 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) track were stockpiled at Toul, along with 20 locomotives and 150 wagons.

The French military had 62 Péchot-Bourdon type built between 1888 and 1914. Baldwin Locomotive Works built 280 more during the war. The "Système Péchot" as it is named in French became the dominant system for trench railways with an estimated 7,500 km (4,700 mi) of track built by the 5th engineer regiment.

250 8-tonne (7.9-long-ton; 8.8-short-ton) 0-6-0T of Decauville's Progres design were built for military service. 32 0-6-0T of American design and 600 55 kW (74 hp) gasoline mechanical locomotives were purchased from Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The Maginot Line employed a 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) gauge supply system of petrol-powered armoured locomotives and underground electric locomotives pulling cars of World War I design. Two Péchot-Bourdon locomotives were preserved in the technical museums of Dresden and the railway museum of Požega. A portion of the Somme battlefield railway continued in operation and has been preserved as the heritage Froissy Dompierre Light Railway.

Baldwin Locomotive Works Péchot-Bourdon locomotive with water-lifter pipe carried on right side tank.

Baldwin Locomotive Works Péchot-Bourdon locomotive with water-lifter pipe carried on right side tank. Decauville 0-6-0T No. 5 built in 1916 and preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway.

Decauville 0-6-0T No. 5 built in 1916 and preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway. Kerr Stuart 0-6-0T "Joffre" class built in 1915 for French government and based on 8 tons Decauville 0-6-0T. Preserved on the West Lancashire Light Railway.

Kerr Stuart 0-6-0T "Joffre" class built in 1915 for French government and based on 8 tons Decauville 0-6-0T. Preserved on the West Lancashire Light Railway. A wagon for transporting artillery shells. A rectangular water tank car is in the background.

A wagon for transporting artillery shells. A rectangular water tank car is in the background.

German equipment

Orenstein and Koppel GmbH manufactured portable track. Krauss designed a 0-6-0T Zwillinge intended to be operated in pairs with the cabs together. The Zwillinge offered Mallet locomotive performance through tight curves, but damage to one unit would not disable the second. One-hundred-eighty-two Zwillinge were manufactured from 1890 to 1903, and shortcomings were evaluated in German South West Africa and China's Boxer Rebellion.

An 11-tonne (24,000 lb) 0-8-0T Brigadelok design with Klien-Lindner articulation of the front and rear axles was adopted as the new military standard in 1901. Approximately 250 were available by 1914, and over two thousand were produced during the war. A Brigadelok typically handled six loaded cars up a 2% grade.

Germany also had approximately five-hundred 0-4-0T, three-hundred 0-6-0T and forty 0-10-0T locomotives of other designs in military service.

Deutz AG produced two-hundred 4-wheel internal combustion locomotives with an evaporative cooling water jacket surrounding the single cylinder oil engine. Fifty similar 6-wheel locomotives were produced by Deutz.

Approximately 20% of the Brigadeloks saw post-war use. Government railways of (Yugoslavia), Macedonia, Serbia and Poland made extensive use of the military locomotives. Significant numbers were used in Hungary, France, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania while smaller numbers went overseas to Africa, Indonesia, Japan and North America. Much of the trench railway equipment remaining in Belgium at the end of hostilities was shipped to the Belgian Congo to build the Vicicongo line.

British equipment

Britain selected a Hunslet Engine Company 4-6-0T design as their standard for the French Decauville 600mm rail gauge; but Hunslet's production of 75 locomotives was insufficient. Baldwin Locomotive Works produced 495 15-tonne (33,000 lb) 4-6-0T of a less satisfactory American design while Hudswell Clarke and Andrew Barclay Sons & Co. built 83 0-6-0T locomotives. One-hundred 15-tonne (33,000 lb) 2-6-2T of the American standard military design were later purchased from Alco's Cooke Locomotive Works for British use.

Britain pioneered the use of petrol powered, 4-wheel synchromesh mechanical drive locomotives (known as tractors) for daylight use within visual range of the front. In 1916 the War Office required "Petrol Trench Tractors" of 600-mm gauge that were capable of drawing 10 to 15 tons at 5 mi (8.0 km) per hour.[3] Early tractors weighed 2 tons. Total production was 102 7 kW (9.4 hp) Ernest E. Baguley tractors, 580 15 kW (20 hp) Motor Rail tractors and 220 30 kW (40 hp) Motor Rail tractors. An additional two-hundred 30 kW (40 hp) petrol-electric tractors were produced by British Westinghouse and Dick, Kerr & Co..

Former British trench railway equipment was put to civilian use rebuilding Vis-en-Artois between Arras and Cambrai. Twenty Hudswell-Clarke and Barclay 0-6-0T, seven Alco 2-6-2T and 26 Baldwin 4-6-0T engines saw service until 1957.

A pair of trench railway tractors in the Minico yard of the Australian 17th Light Railway Operating Company during the Battle of Passchendaele.

A pair of trench railway tractors in the Minico yard of the Australian 17th Light Railway Operating Company during the Battle of Passchendaele. A Hunslet Engine Company 4-6-0T in France at Boisleux-au-Mont, 2 September 1917.

A Hunslet Engine Company 4-6-0T in France at Boisleux-au-Mont, 2 September 1917. One of the Baldwin Locomotive Works 4-6-0T preserved as No. 778 on the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway.

One of the Baldwin Locomotive Works 4-6-0T preserved as No. 778 on the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway. One of the ALCO 2-6-2T preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway in 2007.

One of the ALCO 2-6-2T preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway in 2007.

American equipment

Baldwin Locomotive Works produced 15-tonne (16.5-short-ton; 14.8-long-ton) 2-6-2T numbered 5001-5195. Number 5195 was sent to Davenport Locomotive Works as a pattern for their production of the design, while another was sent to the Magor Car Corporation[4] to test operation of their military railway car production. Two were lost at sea, and the remaining 191 saw service with the U.S. Army in France. Locomotives were initially painted grey with black smoke boxes. White lettering was applied to early production, but black lettering was used in France. Baldwin also built 5-tonne (5.5-short-ton; 4.9-long-ton) 26 kW (35 hp) and 7-tonne (7.7-short-ton; 6.9-long-ton) 37 kW (50 hp) 4-wheel gasoline mechanical locomotives for the U.S. Army. The lighter locomotives were numbered 8001-8063. The heavier locomotives were numbered 7001-7126 and operated at 2 metres per second or 6.56 feet per second (7.2 km/h or 4.5 mph), roughly the speed of a slow jogger.[5]

The standard American military railway car was 170 centimetres (5 ft 7 in) wide and 7 m (23 ft) long riding on two 4-wheel archbar bogies. 1,695 of these cars were built by the Magor Car, American Car and Foundry and Ralston Steel Car Company. Most were flatcars, but some had gondola sides, others had roofs (either with open sides or like conventional boxcars) and others carried shallow rectangular tanks with a capacity of 10,000 litres (2,600 US gal; 2,200 imp gal) of drinking water. The boxcars and tank cars were regarded as top-heavy and prone to derailment; so most loads were carried on flatcars and gondolas. Approximately 1,600 4-wheel side dump cars were produced in several versions for construction earth-moving. The total number of cars shipped to Europe was 2,385.[1]

Davenport Locomotive Works built one-hundred 15-tonne (16.5-short-ton; 14.8-long-ton) 2-6-2T and Vulcan Iron Works built thirty more. Whitcomb Locomotive Works built 74 7-tonne (7.7-short-ton; 6.9-long-ton) 4-wheel gasoline mechanical locomotives. None of the Davenport, Vulcan and Whitcomb production saw overseas service, but some survived to World War II on United States military bases including Fort Benning, Georgia, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, Fort Dix, New Jersey and an arsenal in Alabama.

One of the military 2-6-2T pulling 4-wheel side dump cars for a Michigan construction project in 1921.

One of the military 2-6-2T pulling 4-wheel side dump cars for a Michigan construction project in 1921. The only Baldwin 2-6-2T still in existence and preserved on the "Tacot des Lacs" in France.

The only Baldwin 2-6-2T still in existence and preserved on the "Tacot des Lacs" in France. Baldwin 50 hp gasoline mechanical locomotive here converted to standard-gauge and preserved in France.

Baldwin 50 hp gasoline mechanical locomotive here converted to standard-gauge and preserved in France. American railway wagons preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway.

American railway wagons preserved on the Froissy Dompierre Light Railway.

Russian equipment

During the First World War Russia used both French 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) Decauville and 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in) gauge systems. More than 2,000 km (1,243 mi) of narrow gauge trench railways were built during the war. Kolomna Locomotive Works built 0-6-0T locomotives (I, N, R, T series). 70 locomotives were purchased from ALCO. Baldwin Locomotive Works built 350 seven-tonne 6-wheel gasoline mechanical locomotives for Russia's 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in) gauge in 1916.[6][7]

See also

References

- Ayres, Leonard P. (1919). The War with Germany (Second ed.). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 54.

- "Light Rail Operators, Company D, 21st Engineers". The Great War Society. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- "Motor Rail & Tramcar Co. Ltd., Bedford, England". Old Kiln Light Railway. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- Magor Car Company

- War Activities of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Baldwin Locomotive Works Record, No. 93, 1919; pages 3-21.

- Small 1982 p.55

- Westing 1966 p.76

Bibliography

- Baker, Stuart (1983). "Gas Mechanicals". Narrow Gauge and Short Line Gazette. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - DeNevi, Don & Hall, Bob (1992). United States Military Railway Service America's Soldier Railroaders in WWII. Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press. ISBN 1-55046-021-8.

- Dunn, Rich (1979). "Military Light Railway Locomotives of the U.S.Army". Narrow Gauge and Short Line Gazette. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dunn, Rich (1982). "Military Light Railway Rolling Stock of the U.S.Army". Narrow Gauge and Short Line Gazette. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Seidensticker, Walter (1980). "Brigadeloks and Zwillinge in the Trenches". Narrow Gauge and Short Line Gazette. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Small, Charles S. (1982). Two-Foot Rails to the Front. Railroad Monographs.

- Telford, Robert (1998). "Belligerent Baldwins". British Railway Modelling. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Westing, Fred (1966). The Locomotives that Baldwin built. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-87564-503-8.

- Westwood, John (1980). Railways at War. San Diego, California: Howell-North Books. ISBN 0-8310-7138-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trench railways. |