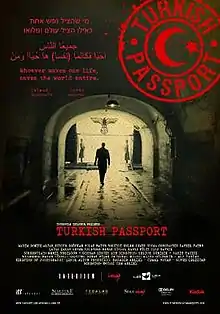

Turkish Passport (film)

Turkish Passport is a 2011 Turkish film directed by Burak Arliel that purports to tell the story of rescue of Jews during the Holocaust by Turkish diplomats. It was promoted as "the only Holocaust film with a happy ending".[1]

| Turkish Passport | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Burak Arliel |

| Written by | Deniz Yeşilgün, Gökhan Zincir |

| Music by | Alpay Göltekin, Alp Yenier |

| Distributed by | Filmpot |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | Turkey |

| Language | Turkish, English & French |

The historical accuracy of the film has been criticized, for presenting unsubstantiated accounts of rescue. Historian Marc David Baer calls it a "propaganda film".[2] Turkish-born historian Uğur Ümit Üngör states that the film is "based on manipulation, mystification, and misrepresentation".[3]

Production

Turkish Jews helped to produce the film. Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör states that "The attitudes of these Jewish community leaders represent the Stockholm syndrome of some minority elites in Turkey, who believe that only absolute conformism to the Turkish government can guarantee their security in the country."[3]

Synopsis

Turkish Passport tells the story of diplomats posted to Turkish embassies and consulates in several European countries, who are presented as saving numerous Jews during the Second World War. Whether they pulled them out of Nazi concentration camps or took them off the trains that were taking them to the camps, the diplomats, in the end, ensured that the Jews who were Turkish citizens could return to Turkey and thus be saved. Based on the testimonies of witnesses who traveled to Istanbul to find safety, Turkish Passport also uses written historical documents and archive footage to tell this story of rescue and bring to light the events of the time. The diplomats saved not only the lives of Turkish Jews, but also rescued foreign Jews condemned to a certain death by giving them Turkish passports. In this dark period of history, their actions lit the candle of hope and allowed these people to travel to Turkey, where they found light. Through interviews conducted with surviving Jews who had boarded the trains traveling from France to Turkey, and talks with the diplomats and their families who saved their lives, the film demonstrates that "as long as good people are ready to act, evil cannot overcome".

At the end of the film, Jews are depicted celebrating after their train crosses the border from Bulgaria into Turkey. This region, contrary to what is portrayed in the film, had been ethnically cleansed of Jews as a result of the 1934 Thrace pogroms.[3]

Awards and coverage at festivals

- The film was shown for the first time at the Cannes Film Festival on May 18, 2011.

- At the 2011 Moondance International Film Festival, it won 'Best Feature Documentary Award' in the Foreigner Category

- Adana Golden Boll Film Festival 2011 - Feature Film Finalist Category -

- Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival 2011 - Special Screening -

- Atlanta Jewish Film Festival 2012 - included to program -

- The European Independent Film Festival 2012 - Foreigner Category, Best Feature Documentary Finalist -

- Zagreb Jewish Film Festival 2012 - included to program -

- UNSPOKEN Human Rights Film 2011 - included to program -

- Amsterdam Turkish Film Festival - participated -

- Yosemite Film Festival 2011 - the winner of the John Muir Award

Historical accuracy

The historical accuracy of the film has been criticized. The claimed rescues are not substantiated beyond the testimony of alleged rescuers. One of the alleged rescuers profiled in the film, Behiç Erkin, was a perpetrator of the Armenian Genocide. Thousands of expatriate Turkish Jews were deported to the death camps because their citizenship was denied by Turkish officials, but this fact is never mentioned in the film. Only one Turkish diplomat, Selahattin Ülkümen, has been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, but he is not covered in the film.[4][3]

Baer states that "Turkish Passport and efforts like it are actually a form of Holocaust denial", since they ignore the fate of Turkish Jews who were killed.[1]

References

- Baer 2020, p. 202.

- Baer 2020, p. 208.

- Uğur Ümit Üngör. "Üngör on Burak Arliel, 'The Turkish Passport' | H-Genocide | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Baer, Marc D. (2020). Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide. Indiana University Press. pp. 199–205. ISBN 978-0-253-04542-3.

External links

- Official website

- Turkish Passport at IMDb

- Filmpot page for the film