Adana

Adana (Turkish pronunciation: [aˈda.na]) is a Cilician city in southern Turkey. The city is situated on the Seyhan River, 35 km (22 mi) inland from the north-eastern coast of the Mediterranean sea. It is the administrative seat of the Adana Province and has a population of 1.77 million.[2]

Adana | |

|---|---|

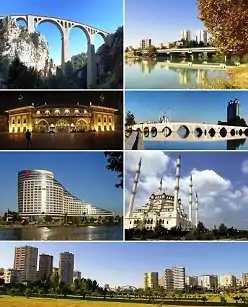

Top: A view from Çukurova, 1st left: Adana station, 1st right: Taşköprü, 2nd left: Sheraton Adana, 2nd right: Sabancı Central Mosque, Bottom: White Houses neighborhood. | |

Adana Location of Adana  Adana Adana (Europe) .svg.png.webp) Adana Adana (Earth) | |

| Coordinates: 37°0′N 35°19.28′E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Mediterranean |

| Province | Adana |

| Founded | 6000 BC (8021 years ago) |

| Incorporated | 1871 (150 years ago) |

| Districts | Seyhan, Yüreğir, Çukurova, Sarıçam |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Body | Adana Metropolitan Municipality |

| • Mayor | Zeydan Karalar (CHP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,945 km2 (751 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 23 m (75 ft) |

| Population (2019)[1] | 1,768,860 |

| • Density | 909.44/km2 (2,355.4/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 01xxx |

| Area code(s) | 0322 |

| Licence plate | 01 |

| Website | www |

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, a distinct geo-cultural region, at a time, was one of the most important regions of the classical world by being crossroads for religions and civilizations.[3] Home to six million people, Cilicia is one of the largest population concentrations in the Near East, as well an agriculturally productive area, owing to its large fertile plain of Çukurova. Adding the large population centers surrounding Cilicia, almost 10 million people reside within two hours' drive from the Adana city center.

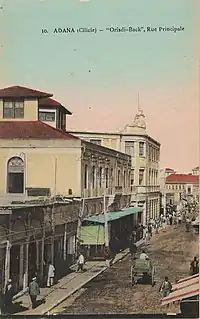

One of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements of the world[4] and with a name unchanged for at least four millennia, Adana was a market town at the Cilicia plain and one of the gateways from Europe to the Middle East. The city turned into a powerhouse of Cilicia with the Turkic takeover in 1359. It remained as the capital of the Ramadanid Emirate until 1608, and then the regional center for the Ottoman Empire, Turkey and shortly for the French Cilicia. The city boomed with the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, and emerged as a hub for international cotton trade. Traditionally a town populated by Armenians and Turks; influx of Assyrians, Greeks, Circassians, Jews and Alawites during this period made the city one of the most diverse cities of the Empire. Economic, social and cultural growth was halted by the Adana massacre, the Armenian Genocide, and the 1921 Cilicia evacuation,[5] all of which devastated the city in the early 20th century. After the eviction of Christian community, most of the city's private properties, value-wise, were confiscated in 1923 and were granted to the Muslim Turks who recently had migrated into the city. After a standstill period, city's economy again boomed in the 1950s with the construction of the Seyhan Dam, and the growth continued until the 1980s.

In the 21st century, Adana is a center for regional trade, healthcare, and public and private services. Agriculture and logistics are significant sectors of the city. The economic decline caused by national policies and de-industrialization since the 1990s is reversing, as the city is gaining momentum with the fairs, festivals and entertainment life. The rivalry between the city's football clubs, Adanaspor and Adana Demirspor, is getting attraction as being a derby that is rooted in socio-economic divisions.

Etymology

One theory holds that the city name originates from a hypothetical Indo-European term; a danu (English: on the river). Many river names in Europe were derived from the same Proto-Indo-European root: Danube, Don, Dnieper and Donets.[6] The earliest time Adana was mentioned was around 2000 BC in the Hittite tablets. With a history of at least four millennia, Adana is one of the oldest continuously used place names and had only pronunciation changes under different rules.

In Homer's Illiad, the name of the city is mentioned as Adana. For a short while during the Hellenistic era, the city was known as Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Κιλικίας (English: Antioch in Cilicia) and as Ἀντιόχεια ἡ πρὸς Σάρον (English: Antioch on Sarus). On some cuneiforms, the city name was mentioned as Quwê, and as Coa in some other sources which could be the place Solomon had obtained his horses as per Bible (I Kings 10:28; II Chronicles 1:16). Under the Armenian rule, the city was known as Ատանա (Atana) or Ադանա (Adana). An ancient Greco-Roman legend mentions that the name of Adana originates from Adanus, the son of the Greek god Uranus, who founded the city next to the river with his brother.[7] His brother's name, Sarus, was given to the river. An older legend, in Accadian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Hittite mythologies, originates the city's name to the Storm and rain god Adad who lived in the surrounding forests. There are Hittite manuscripts that were founded in the region regarding this legend. The legend had survived as the Storm and rain god continued to create rain and abundance. The locals had great admiration towards the God and called the region Uru Adaniyya (English: Adana region) in his honour. The city inhabitants were called Danuna.

According to Ali Cevad's Memalik-i Osmaniye Coğrafya Lügatı (English: Ottoman Geography Dictionary), Muslims of Adana originated the city's name to Ebu Süleym Ezene, who was appointed as Wali by Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[8] Other than Ezene, Ottoman and Islamic resources also mention the city as Edene, Azana and Batana.

It is also believed that it is related to the "Danaoi", the name for Greeks of the Trojan War in Homer and Thukydides.[9]

Geography

Adana is located on the 37th parallel north at the northeastern edge of the Mediterranean, where it serves as the gateway to the Cilicia plain. This large stretch of flat, fertile land lies southeast of the Taurus Mountains. From Adana, crossing Cilicia westwards, the road from Tarsus enters the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, eventually reaching an altitude of nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m). It goes through the famous Cilician Gates, the rocky pass through which armies have coursed since the dawn of history, and continues to the Anatolian plain.

The Seyhan River (formerly called the Sarus) that passes through Adana, occasionally flooded the city until embankments were built in the 1900s.[10] The north of the city is surrounded by the Seyhan reservoir. The Seyhan Dam, completed in 1956, was constructed for hydroelectric power and to irrigate the lower Çukurova plain. Two irrigation channels in the city flow to the plain, passing through the city center from east to west. There is another canal for irrigating the Yüreğir plain to the southeast of the city.

Climate

Adana has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) under both the Köppen classification, and a dry-hot summer subtropical climate (Csa) under the Trewartha classification. Winters are mild and wet. Frost does occasionally occur at night almost every winter, but snow is a very rare phenomenon. Summers are long, hot, humid and dry. During heatwaves, the temperature often reaches or exceeds 40 °C (104.0 °F). The highest recorded temperature was on 8 July 1978 at 45.6 °C (114.1 °F). The lowest recorded temperature was −8.1 °C (17.4 °F).

| Climate data for Adana (1927–2017) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.5 (79.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

41.3 (106.3) |

42.8 (109.0) |

44.0 (111.2) |

45.6 (114.1) |

43.2 (109.8) |

41.5 (106.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

45.6 (114.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.8 (92.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.5 (49.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.7 (83.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.2 (52.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 107.6 (4.24) |

90.0 (3.54) |

65.4 (2.57) |

51.3 (2.02) |

47.3 (1.86) |

20.4 (0.80) |

6.3 (0.25) |

5.6 (0.22) |

17.8 (0.70) |

42.1 (1.66) |

71.7 (2.82) |

119.1 (4.69) |

644.6 (25.38) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.1 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 11.4 | 86.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 139.5 | 149.7 | 186.0 | 213.0 | 282.1 | 318.0 | 334.8 | 322.4 | 270.0 | 229.4 | 177.0 | 136.4 | 2,758.3 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 4.5 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 10.6 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 7.5 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[11] | |||||||||||||

History

Adana is considered to be the oldest city of Cilicia, and with a history of 8-millennia, it is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities of the world. The history of the Tepebağ tumulus dates back to the Neolithic, to around 6000 B.C., the time of the first human settlements. A place called Adana is mentioned by name in a Sumerian epic, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

First known people living in Adana and the surrounding area were the Luwians. They controlled the Mediterranean coasts of Anatolia roughly from 3000 BC to around 1600 BC. Hittites took over the region which came to be known as Kizzuwatna. Inhabited by Luwians and Hurrians, Kizzuwatna had an autonomous governance under the Hittites protection, but they had a brief independent period from the 1500s to 1420s. According to the Hittite inscription of Kava, found in Hattusa (Boğazkale), Kizzuwatna was the kingdom that ruled Adana, under the protection of the Hittites by 1335 BC. Beginning with the collapse of the Hittite Empire c. 1191–1189 BC, Adana native Denyen sea peoples took control of the plain until around 900 BC.[12] Neo-Hittite States founded in the region then after and Quwê state was centered around Adana. Quwê and other states were protected by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, though they had independent periods. After the Greek migration to Cilicia in the 8th century BC, the region was unified under the rule of Mopsos dynasty[13] and Adana was established as the capital. Bilingual inscriptions of the ninth and eighth centuries found in Mopsuestia were written in hieroglyphic Luwian and Phoenician. Assyrians took control of the regions several times until their collapse in 612 BC.

Cilicians founded the Kingdom of Cilicia in 612 BC with the efforts of Syennesis I. The kingdom was independent until the invasion of Achaemenid Empire in 549 BC, then after, became an autonomous satrapy of Achaemenids until 401 BC. The uncertain loyalty of the Syennessis during the rebellion of Cyrus the Younger led Artaxerxes II to abolish the Syennesis administration and replace it with a centrally appointed satrap. Archeological remains of a procession reveals the existence of Persian nobility in Adana.[14]

Alexander had an unexpected entry into Cilicia in 333 BC through the Cilician Gates and appointed the Syennesis dynasty to re-administer the region. His death in 323 BC marked the beginning of the Hellenistic era, as Greek replaced Luwian as the language of the region. After a short time under the Ptolemaic dominion, Seleucid Empire took control of the region in 312 BC. Adanan locals had adopted a Greek name for the city, Antioch on Sarus, to demonstrate loyalty to the Seleucid dynasty. The adopted name and the motifs illustrating the personification of the city seated above the river-god Sarus on city's minted coins, reveal appreciation to the rivers which were strong part of the Cilician identity.[15] Although the Adana area were into international trade, coasts of rugged Cilicia were under the heavy plunder of the Cilician pirates. Seleucids ruled Adana for more than two centuries until weakened by the civil war which led them to offer allegiance to Tigranes II, the King of Armenia who conquered a vast region in the Levant. Cilicia became a vassal state of the Kingdom of Armenia in 83 BC and new settlements were founded by Armenians in the region.[16]

Roman-Byzantine, Islamic and Armenian era

Pompey took over entire Cilicia and organized it as a Roman province in 64BC. Adana was of relatively minor importance during the Roman's influential period, while nearby Tarsus was the metropolis of the area. During the era of Pompey, the city was used as a prison for the pirates of Cilicia. The Sarus bridge was built in the early 2nd century, and for several centuries thereafter, the city was a waystation on a Roman military road leading to the East. After the permanent split of the Roman Empire in 395 AD, the area became a part of the Byzantine Empire, and was probably developed during the time of Julian the Apostate. With the construction of large bridges, roads, government buildings, irrigation and plantation, Adana and Cilicia became the most developed and important trade centers of the region.

Adana was a Christian bishopric, a suffragan of the metropolitan see of Tarsus, but was raised to the rank of autocephalous archdiocese after 680, the year in which its bishop appeared as a simple bishop at the Third Council of Constantinople, but before its listing in a 10th-century Notitiae Episcopatuum as an archdiocese. The Bishop Paulinus participated in the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Piso was among the Arianism-inclined bishops at the Council of Sardica (344) who withdrew and set up their own council at Philippopolis; he later returned to orthodoxy and signed the profession of Nicene faith at a synod in Antioch in 363. Cyriacus was at the First Council of Constantinople in 381. Anatolius is mentioned in a letter of Saint John Chrysostom. Cyrillus was at the Council of Ephesus in 431 and at a synod in Tarsus in 434. Philippus took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451[17] and was a signatory of the joint letter of the bishops of Cilicia Prima to Byzantine Emperor Leo I the Thracian in 458 protesting at the murder of Proterius of Alexandria. Ioannes participated in the Third Council of Constantinople in 680.[18][19] No longer a residential bishopric, Adana is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[20]

At the Battle of Sarus in April 625, Heraclius defeated the Sasanian Shahrbaraz forces that are stationed at the east bank of the river, after a fearless charge across the Justinian bridge (now Taşköprü).[21] Byzantines defended the region from encroaching Islamic Caliphates throughout the 7th century CE, but it was finally conquered in 704 by the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik. During Umayyad rule, Cilicia became a no man's land frontier between Byzantine Christian and Arab Muslim forces.[3] In 746, profiting by the unstable conditions in the Umayyad Caliphate, Byzantine Emperor Constantine V took control of Adana in 746. Abbasid Caliphate took over the rule of the region from Byzantine after Al-Mansur's inauguration to caliph in 756. With the Abbasid rule, Muslims for the first time started settling in Cilicia. Abandoned for more than 50 years, Adana was garrisoned and re-settled from 758 to 760. To form a Thughūr on the Byzantine frontier, Cilicia was colonized with the Turkic Sayābija tribe from Khorasan. The city had seen rapid economic and cultural growth during the reign of Harun al-Rashid and Al-Amin. Abbasid rule of the city continued for more than two centuries,[22] and the Byzantines retook control of Adana in 965. The city became part of the Seleucia theme. After the defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the emperor Romanos IV Diogenes was removed from reign by a coup. He then gathered a troop to regain his power, though got defeated and had to retreat his troop to Adana. He was forced to surrender by the garrison in Adana upon receiving assurances of his personal safety.

Suleiman ibn Qutulmish, the founder of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, annexed Adana in his campaign in 1084. Cilicia had been criss-crossed by invading armies and the crusades during this period until it was captured by the forces of the Armenian Principality of Cilicia in 1132, under its king, Leo I.[23] It was taken by Byzantine forces in 1137, but the Armenians regained it around 1170. Armenian era had evolved Adana to a center for handicrafts and international trade. The city was the center of a large trading network from Minor Asia to North Africa, Near East and India. Venetian and Genoese merchants frequented the city to sell their goods that were brought through Ayas port.[24] In 1268, the devastating Cilicia earthquake destroyed much of the city and 80 years later in 1348, Black Death reached the region and caused severe depopulation. Adana remained part of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia until 1359, when the city was ceded to the Türkmen supported Mamluk Sultanate who marched into Cilicia and captured the plain. Most Armenians of the city fled to Cyprus after the ceding.

Turkish era

The Mamluks built garrisons in Tarsus, Ayas port and Sarvandikar, and left the administration of Adana plain to Yüreğir Turks who already formed a Mamluk authorized Türkmen Emirate in Camili area in 1352, just southeast of Adana. The Amir, Ramazan Bey, designated Adana as the capital, and headed the Yüreğir Turks in settling the city. The emirate which later on known as the Ramadanid Emirate, were de facto independent throughout the 15th century, by being a Thughūr in the Ottoman-Mamluk relations. In 1517, Selim I incorporated the beylik into the Ottoman Empire after his conquest of the Mamluk state. The Ramadanid Beys held the administration of the new Ottoman sanjak of Adana in a hereditary manner until 1608.

.jpg.webp)

Ottomans terminated the Ramadanid administration in 1608 after the Celali rebellions and commenced ruling directly from Constantinople through an appointed Vali.[25] In late 1832, Vali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, invaded Syria, and reached Cilicia. The Convention of Kütahya that was signed on 14 May 1833, ceded Cilicia to the de facto independent Egypt. At the time of ceding, the Adana sanjak population of 68,934 hardly received any urban services.[26] First neighborhood (Verâ-yı Cisr) east of the river was founded and Alawites brought here from Syria to work at the flourishing agricultural lands. İbrahim Paşa, the son of Muhammad Ali Paşa, demolished the Adana Castle and the city walls in 1836. He built the first canals for irrigation and transportation and also built a water system for the residential areas of the town, including wheels (tr:mavra) raising the water of the river for public fountains.[27] After the Oriental crisis, the Convention of Alexandria that was signed on 27 November 1840, required the return of Cilicia to Ottoman sovereignty. The American Civil War that broke down in 1861, faltered the cotton flow to Europe and directed European cotton traders to fertile Cilicia. Adana had evolved to be a hub for cotton trade and one of the most prosperous cities of the Empire within decades. New Armenian, Turkish, Greek, Chaldean, Jewish and Alawite neighborhoods were founded, surrounding the formerly walled city. Adana–Mersin railway line was opened in 1886, connecting Adana to international ports through Port of Mersin. Further migration that had attracted by the large-scale industrialization, inflated the population of Adana to over 107,000 at the turn of the 20th century: 62,250 Muslims (Turks, Alawites, Circassians, Kurds), 30,000 Armenians, 8000 Chaldeans, 5000 Greeks, 1250 Assyrians, 500 Arab Christians and 200 internationals.[28]

Adana massacre

Wealth acquired with the thriving regional economy, doubling of Cilician Armenian population due to flee from Hamidian massacres, the end of autocratic Abdulhamid rule with the revolution of July 1908, empowered the Armenian community and envisioned an autonomous Cilicia. CUP's post-revolution mismanagement of Vilayets, caused pro-diversity Vali Bahri Pasha to be removed from the office in late 1908, and replaced him with the impotent Cevad Bey. Taking that into advantage, Bağdadizade Abdülkadir (later Paksoy), the local leader of Cemiyet-i Muhammediye, took almost control of the local governance and led an action plan in entire Cilicia to "punish" Armenians. Rumours of an upcoming Armenian attack, deliberate provocations tensed the Turkish neighborhoods. As soon as the news of countercoup reached Cilicia, enraged members of Cemiyet-i Muhammediye[29] and dissatisfied peasants that were left out of work due to mechanization, flocked to the city on the market day of Tuesday. After staying overnight in the city, the groups together with the local supporters started attacking the Armenian shops from the morning of 14 April 1909. The attacks directed towards the Armenian dwellings later in the day and also spread to rest of Cilicia. Armed Armenians could defend themselves and the clashes lasted until April 17.

After a week of silence, 850 soldiers from regiments of the Ottoman Army arrived to the city on April 25. Shots were fired to the tents that soldiers set at the campground, and a rumor immediately spread that the Armenians had opened fire from a church tower. Without even investigating any falsity of the rumor, the military commander Mustafa Remzi Pasha directed soldiers, together with the bashi-bazouks, towards Armenian quarters and for three days; shot people, destroyed buildings and burned down Christian neighborhoods. Pogroms of 25–27 April were much larger than the 14–17 April clashes, and the casualties were almost all Christian.[30]

The Adana massacre of April 1909, resulted in the deaths of 18,839 Armenians, 1250 Greeks, 850 Assyrians, 422 Chaldeans and 620 Muslims. Adding the roughly 2500 disappeared Hadjinian and other seasonal workers, the death roll is estimated around 25,500 in the entire Vilayet. Later in summer, 2000 children died of dysentery and few thousand adults died of injuries or epidemic. The massacre orphaned 3500 children and caused heavy destruction of Christian properties.[31][32] Cevad Bey and Mustafa Remzi Pasha were sacked and lightly sentenced for abuse of power, and on 8 August 1909, Djemal Pasha was appointed as the Vali, who quickly built relations with the surviving Armenian community. With the financial support he could gather, Djemal Pasha founded a new neighborhood, Çarçabuk (now Döşeme), for Armenians within a very short time, ordered the construction of two orphanages and the restoration of destroyed buildings.[29] Cilicia section of the Berlin–Baghdad railway had opened in 1912, connecting Adana to Middle East. In few years, the city had re-gained its momentum and by the turn of 1915, the Armenian population numbered up to 30,000, close to the figure before 1909.

The city during Armenian Genocide

Early in May 1915, Vali Ismail Hakkı Bey received an order from Constantinople (now İstanbul) to deport the Armenians of the city. Vali was able to delay the deportations and let the Armenians to sell their movable assets to acquire money for the trip. First convoy of deportees consisting of more than 4000 Armenians left the city on May 20. The Catholicos of Cilicia, Sahak II wrote a letter to Djemal Pasha, then Syria-Cilicia General Vali, to prevent further deportations and the chief secretary Kerovpe Papazian met the pasha in Aley in early June and delivered the message of Catholicos. Djemal Pasha immediately wired the Vali to not to deport more Armenians. With his efforts, Adana Armenians earned an exemption at a summer, while the rest of Cilician Armenians were being deported and hundreds of thousands of exhausted Armenian deportees of Western Anatolia were passing through the city. Armenian intellectuals that were deported on April 24th from Constantinople, Rupen Zartarian, Sarkis Minassian, Nazaret Daghavarian, Harutiun Jangülian, and Karekin Khajag were kept in custody at the Vilayet Hall for few days. They could manage to have a meeting with the Catholicos at the Cathedral; their last attempt for survival. Later in June, two prominent leaders, Krikor Zohrab and Vartkes Serengülian were also kept in the city on their final journey towards Diyarbakır.[33]

Minister of Interior, Talaat Pasha, wanted to end the exemption of Adana Armenians and sent his second in command in the Ministry, Ali Munif, to the city in mid-August to resume the deportations. Ali Munif immediately deported 250 families from Adana who were accused of insurrection and executed many Armenians daily at Kuruköprü Square. Before the deportations of the rest, Vali could again manage the deportees to sell their assets. As almost a third of the city residents were selling their goods, the city seemed like a site for massive clearance sale. Deportations of 5000 Armenian families in eight convoys started on 2 September 1915 and continued until the end of October. 1000 craftsmen, state officers and the army personnel were exempted from deportations with their families. Unlike the deportees of other Vilayets, a good portion of Adana Armenians were sent to Damascus and further south, thus were avoided from the death camps of Deir ez-Zor by the personal request of Djemal Pasha.[33] At the course of Armenian Genocide, the death rate of the roughly 25,000 Adana Armenians that were deported through out 1915, were a lot lower than the deportees from other regions due to three main factors: No reports of direct killings in and around the city, a portion being deported to Damascus area and having money with them to manage their lives on the way and after arriving to their designated locations.

French rule

![]() Hittites 1600s–1500s

Hittites 1600s–1500s

Kizzuwatna (free) 1500s–1420s

![]() Hittites 1420s–1190s

Hittites 1420s–1190s

Denyen Sea Peoples 1190s–c.900

![]() Quwê / Assyria c.900–612

Quwê / Assyria c.900–612

![]() Kingdom of Cilicia 612–549

Kingdom of Cilicia 612–549

![]() Achaemenid Empire 549–333

Achaemenid Empire 549–333

![]() Empire of Alexander 333–323

Empire of Alexander 333–323

![]() Ptolemaic Kingdom 323–312

Ptolemaic Kingdom 323–312

![]() Seleucid Empire 312–83

Seleucid Empire 312–83

![]() Kingdom of Armenia 83–64

Kingdom of Armenia 83–64

![]() Roman Empire 64BC–395AD

Roman Empire 64BC–395AD

![]() Byzantine Empire 395–704

Byzantine Empire 395–704

Umayyad Caliphate 704–746

![]() Byzantine Empire 746–756

Byzantine Empire 746–756

![]() Abbasid Caliphate 756–965

Abbasid Caliphate 756–965

![]() Byzantine Empire 965–1084

Byzantine Empire 965–1084

![]() Seljuk / Crusades 1084–1132

Seljuk / Crusades 1084–1132

![]() Armenian Principality of Cilicia 1132–1137

Armenian Principality of Cilicia 1132–1137

![]() Byzantine Empire 1137–1170

Byzantine Empire 1137–1170

![]() Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia 1170–1359

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia 1170–1359

![]() Ramadanid Emirate 1359–1608

Ramadanid Emirate 1359–1608

![]() Ottoman Empire 1608–1833

Ottoman Empire 1608–1833

![]() Egypt Eyalet 1833–1840

Egypt Eyalet 1833–1840

![]() Ottoman Empire 1840–1918

Ottoman Empire 1840–1918

![]() French Cilicia 1918–1922

French Cilicia 1918–1922

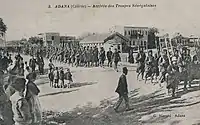

Armistice of Mudros that was signed on 30 October 1918 to end the World War I, ceded the control of Cilicia to France. French Government sent four battalions of the Armenian Legion in December to take over Adana and oversee the repatriation of more than 170,000 Armenians to Cilicia. Returning Armenians negotiated with France to establish an autonomous State of Cilicia and Mihran Damadian, the chief negotiator for Armenians, signed the provisional Constitution of Cilicia in 1919.[5] Pre-war life had resumed with re-opening of the churches, the schools, the cultural centers and the businesses.

The French forces were spread too thinly in Cilicia and the villages that were repatriated came under withering attacks by Turkish Kuva-yi Milliye. Costs and difficulties associated with the repatriation process, growing Arab nationalism in Syria mandate, forced French High Commissioners to meet with Turkish leader, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, several times in late 1919 and early 1920 which resulted in halting the deployment of extra forces to Cilicia.[34] A truce arranged on May 28 between the French and the Kemalists, led to the retreat of the French forces south of the Mersin-Osmaniye railroad. The subsequent evacuation of thousands of Armenians from Sis and its environs and their migration to Adana, raised the number of Armenians in the city to more than 100,000.[35] Throughout June, the Armenian Legion, repatriated Armenians and Assyrians had committed vengeful acts on Turks, killing hundreds around Kahyaoğlu, Kocavezir, Camili and İncirlik.[36] On 10 July 1920, to ease the overpopulated south of the railroad, a Franco-Armenian operation forced the local Turkish population to escape north. Roughly 40,000 Turks from Adana and around fled to the countryside and to the mountains north, an event known as Kaç Kaç incident, which lasted 4 days and claimed hundreds of lives.[37] Mihran Damadian declared the autonomy of Cilicia on 5 August 1920, by coming to a consensus with the Christian communities of the city. French government, however, did not recognize the autonomy, expelled the community leaders and disbanded the Armenian Legion in September.[33]

With the changing political environment and interests, French further reversed their policy and abandoned all pretensions to Cilicia, which they had originally hoped to attach to their mandate over Syria.[35] Cilicia Peace Treaty was signed on 9 March 1921 between France and Turkish Grand National Assembly. The treaty did not achieve the intended goals and was replaced with the Treaty of Ankara that was signed on 20 October 1921. Based on the terms of the agreement, France recognized the end of Cilicia War and to the withdrawal under the condition of Christian communities' rights to be protected.[38] Armenians who were not satisfied with the guarantees that the treaty offer and who had no trust in Turkish nationalist rule after the catastrophes of 1909 and 1915, had rushed to the Mersin port and Dörtyol, and had evacuated their two-millennia homeland by December 1921.[39] French troops together with the remaining Armenian volunteers withdrew from the city on 5 January 1922. Later in 1922, up to 10,000 Adana Greeks moved to Greece before the policy of Greco-Turkish population exchange got in effect.[5][40] Adana Armenians settled in Lebanon, where they founded Nor Adana (en:New Adana) neighborhood within the mostly Armenian Bourj Hammoud town, just north-east of Beirut.[41] From the 1920s, around 60 percent of the Cilician Armenians moved to Argentina. An informal census of 1941 revealed that, 70 percent of all the Armenian Argentines in Buenos Aires had Adana origins.[42]

Modern Turkey

On 15 April 1923, just before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the Turkish government enacted the "Law of Abandoned Properties" which confiscated the properties of Armenians and Greeks who were not present on their property. Adana were one of the cities with the most confiscated property, thus muhacirs from Balkans and Crete, migrants from Kayseri and Darende were relocated in the Armenian and Greek neighborhoods of the city. All types of modest properties, lands, houses and workshops were distributed to them. Large farms, factories, stores and mansions were granted to the Kayseri notables (e.g. Nuh Naci Yazgan, Nuri Has, Mustafa Özgür) and to local nationalists (e.g. Sefa Özler, Ali Münif) as promised at the Sivas Congress by Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk).[43] Within a decade, the city had a sharp change demographically, socially and economically and lost its diversity by turning into a solely Muslim/Turkish city.[5] Remaining Jews and Christians were hit by the heavy burden of the Wealth Tax in 1942, which caused them to leave Adana, selling their properties way under the value to families like Sabancı, who built their wealth on owning confiscated or undervalued properties. Forcible change in means of production led to abuse of wealth and harsh treatment of labor later in the 20th century, as the new possessors did not have the management attributes that the previous owners had.

The city was hit by a 6.2 magnitude earthquake (1998 Adana–Ceyhan earthquake) on 27 June 1998. The disaster killed 145 and left 1500 people wounded and many thousand homeless in the city and in Ceyhan district. The total economic loss was estimated at about US$1 billion.[44]

Governance

The city of Adana is referred as the area that is within the borders of Adana Metropolitan Municipality. This area covers 30 km2 (12 sq mi) around the City Hall excluding the areas out of the Province.[45] Four levels of government are involved in the administration of the city; national government, provincial administration, metropolitan municipality and the district municipalities. Government of Turkey in Ankara holds most of the power; health, education, police and many other city related services are administered by Ankara through an appointed Governor. National government is also the lawmaker, adjudicator and auditor of all the other levels of government and the neighborhood administration. Semi-democratic provincial governing body, Adana Province Special Administration, has minor powers, dealing mainly with construction and maintenance of primary schools, daycares and other state buildings and some level of social services.[46] Municipal governance is held in a two-tier structure; Metropolitan Municipality forms the upper and the district municipalities form the lower tier. Metropolitan municipality takes care of construction and maintenance of major roads and parks, operating local transit and fire services.[47] District municipalities are responsible for neighborhood streets, parks, operating garbage collection and cemetery services. The district municipalities are further divided into neighborhoods (mahalle), the smallest administrative units of the city.

Metropolitan municipality

Adana Municipality was incorporated in 1871 though the city continued to be governed by the muhtesip system until 1877 by the first mayor Gözlüklü Süleyman Efendi. The first modern municipal governance began with the second mayor Kirkor Bezdikyan and his successor Sinyor Artin. The roads were widened and paved with cobblestone, drainage canals and trenches were opened, more importantly the first municipal regulations were put in effect. After the foundation of the republic, major infrastructure projects were completed and the first planned neighborhoods were built north of the city. Turhan Cemal Beriker served as mayor and governor for 12 years during this period. With the completion of Seyhan Dam in 1956, the city saw explosive growth when then prime minister Adnan Menderes showed special interest in Adana; he initiated large-scale infrastructure projects like citywide underground sewer systems and rezoning of residential areas into roads and public spaces. From 1984 to the present, the cityscape has seen revolutionary changes with the revitalization of Seyhan river and the construction of large parks and boulevards.[48]

Metropolitan Municipality Law was introduced in 1989 and the municipal governance was split between metropolitan municipality and district municipalities. Adana Municipality then became the Metropolitan Municipality and two new district municipalities were founded; Seyhan and Yüreğir. Karaisalı was annexed to the city in 2006, Çukurova and Sarıçam districts were founded in 2008 by the partitioning of Seyhan and Yüreğir districts respectively. On 3 February 2012, Karataş Municipal Council accepted a motion to amalgamate the municipality with Adana, hence Karataş will become the sixth district of the city after the transition process is completed.[49]

Metropolitan municipality consists of three organs; Metropolitan Council, Mayor and the Encümen. Each district municipal council elects one-fifth of their members to represent the district at the metropolitan council. Thus, metropolitan council consists of 35 councilors, ten from Seyhan district, eight from Yüreğir, eight from Çukurova, six from Sarıçam, two from Karaisalı and the metropolitan mayor who is elected directly by the voters.[50] Encümen, the executive committee, consists of ten members, five being metropolitan councilors and the other five are the directors at the metropolitan hall who are appointed to the Encümen by the metropolitan mayor.[51]

Districts

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

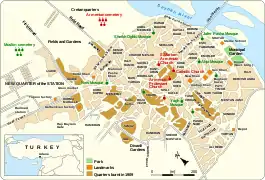

City of Adana consists of the urban areas of the four metropolitan districts; Seyhan, Yüreğir, Çukurova, Sarıçam. Seyhan district is fully within the city limits whereas Yüreğir, Çukurova and Sarıçam districts have rural areas outside the city.

Seyhan district, located west of Seyhan River, is the cultural and business center of the city. D-400 state road (also called Turhan Cemal Beriker Boulevard within the city limits) divides the district into north and south. Seyhan's north of D-400, is economically the most developed part of the city. Hotels, cultural centers, commercial and public buildings line up along D-400. Old town, located south of D-400, is the market place where traditional and modern shops serve the residents. South of the old town is a low-income residential area.

Çukurova district is a modern residential district that lies north of the Seyhan district and south of the Seyhan Reservoir. The district was planned in the mid-1980s to direct the urban sprawl to low-fertile 3000 hectare land north of the city. Named as New Adana, the project consisted of 200,000 homes including villas along the lake shore and high-rise apartment buildings along the newly opened wide boulevards of Turgut Özal, Süleyman Demirel and Kenan Evren.[52]

Yüreğir district, located east of the river, consists mainly of low-income residential areas and large-scale industries. With the construction of new bridges on the river and the extension of metro line to the district, Yüreğir became increasingly important, Adana Court of Justice re-locating to the district and a 47.5-hectare health campus planned to be built in the Kazım Karabekir neighborhood.[53] An extensive urban redevelopment plan is under effect in the district which will convert the neighborhoods of Sinanpaşa, Yavuzlar, Köprülü and Kışla into modern residential areas.[54]

District of Sarıçam lies north and east of Yüreğir, consisting of former municipalities that were amalgamated to the City of Adana in 2008. Some of the large institutions of the city are in Sarıçam: Çukurova University, İncirlik Air Base and the Organized Industrial Region.

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods (Mahalle) are administrative units within the district municipalities and are administered by the muhtar and the Neighborhood Seniors Council. Although elected by the neighborhood residents, the muhtar is not granted any powers, thus functions as an administrator of the national government. Muhtar can voice neighborhood issues to the district municipality and do have a seat at the Adana City Assembly, an umbrella organization for the coordination of public institutions in the city.[55] Despite the fact that neighborhood administration cannot provide social services nor have funding to increase the involvement of residents in neighborhood issues, many residents still like to identify themselves strongly with their neighborhoods especially in the low-income areas.

There are a total of 254 neighborhoods in the city. Seyhan has 99 neighborhoods, 69 of them in the urban area and 30 are the neighborhoods of the former municipalities and the former villages that converted into neighborhoods. Yüreğir has 99 neighborhoods, 38 in the urban area and 61 rural. There are 29 neighborhoods in Sarıçam, 16 neighborhoods in Çukurova and 11 in Karaisalı district. A neighborhood population can range from 150 to 63,000.[56] Some neighborhoods, especially in the Çukurova district, are very large—almost the size of a town—making resident access to muhtars difficult.

Tepebağ, Kayalıbağ, Kuruköprü, Ulucami, Sarıyakup and Alidede are the historical neighborhoods of Adana. The planned neighborhoods of the republican era, Reşatbey, Cemalpaşa, Kurtuluş and Çınarlı are the core of cultural life in the city. Güzelyalı, Karslılar and Kurttepe are the scenic neighborhoods overlooking the Seyhan reservoir.

Economy

_Mountain_(3756_m)._Aladaglar_National_Park.jpg.webp)

Adana is one of the first industrialized cities, as well as one of the economically developed cities of Turkey. A mid-size trading city until the mid-1800s, the city attracted European traders after the United States, a major cotton supplier, was embroiled with its Civil War. Cilicia farmers exported agricultural products for the first time and started building capital. By the start of the 20th century, factories almost all processing cotton, began to operate in the region. Factories were shut down and the economy almost came to a standstill in 1915, after the genocide of Armenians who ran most of the businesses in the city. Foundation of the republic, again accelerated the growth of industrialization by re-activation of closed plants and opening of state-owned ones. With the construction of Seyhan Dam and improvements in agricultural techniques, there was an explosive growth in agricultural production during the 1950s. Large-scale industries were built along D-400 state road and Karataş road. The service industry, especially banking, developed during this period.[57] Rapid economic growth continued until the mid-1980s and was accompanied by the rise of capitalistic greed which attracted movie makers to the region, filming income inequalities and the abuse of wealth.

Extensive neo-liberal policies by then Prime Minister Turgut Özal to centralize the country's economy, caused almost all Adana-based companies to move their headquarters to Istanbul. The decline in cotton planting in the region raised the raw material cost for manufacturing, thus the city has seen a wave of plant closures starting from the mid-1990s.[58] Young professionals fled the city, contributing to Adana's status as the top brain drain city of Turkey. Financial and human capital flight from Adana further increased since 2002 with the current national governing party, AKP, due to neo-liberal centralization policies similar to Özal's and in addition, hidden policy not to invest in major projects in a city nonaligned with AKP version of conservatism. In 2010, unemployment in the city reached a record high of 19.1 percent.[59] After 20 years of stagnation, the economy of Adana is picking up recently with investments in the tourism and service industry, wholesale and retail sectors and the city is re-shaping as a regional center.

Adana was named among the 25 European Regions of the Future for 2006/2007 by Foreign Direct Investment magazine. Chosen alongside Kocaeli for Turkey, Adana scored the highest points for cost effectiveness against Kocaeli's points for infrastructure development, while Adana and Kocaeli tied on points for the categories of human resources and quality of life.[60]

Commerce

A leading commercial center in southern Turkey, the city hosts regional headquarters of many corporate and public institutions. TÜYAP Exhibition and Congress Center hosts fairs, business conferences and currently it is the main meeting point for businesses in Çukurova.[61] Academic oriented 2000-seater Alper Akınoğlu Congress Center is expected to open in 2012 at Çukurova University campus.[62]

Adana Chamber of Commerce (ATO) was founded in 1894 to guide and regulate the cotton trade and it is one of the oldest of its kind in Turkey. Today the Chamber has more than 25,000 member companies, furthers the interests of businesses and advocates on their behalf.[63] Adana Commodity Exchange, founded in 1913, functions mainly to organize the trade of agricultural produce and livestock in a secure and open manner. The Exchange is located across the Metropolitan Theatre Hall.[64]

Designation of coastal areas of Ceyhan and Yumurtalık districts as Energy-specific Industrial Areas has made Adana an attraction for hotel building. Current capacity of 29 hotels hosting 4200 guests will double in two years; total number of hotel beds rising to 8400.[65] Current 5-star hotels of the city, Hilton, Seyhan and Sürmeli will be complemented by Sheraton and Türkmen hotels on the river bank, Ramada and Divan hotels in the city center, Anemon hotel at the west end which are all currently under construction.[66]

Agriculture

Adana is the marketing and distribution center for Çukurova agricultural region, where cotton, wheat, corn, soy bean, barley, grapes and citrus fruits are produced in great quantities. Farmers of Adana produce half of the corn and soy bean in Turkey. 34 percent of Turkey's peanuts and 29 percent of Turkey's oranges are harvested in Adana.[67] Most of the farming and agricultural-based companies of the region have their offices in Adana. Producer co-operatives play a significant role in the economy of the city. Çukobirlik, Turkey's largest producer co-operative, has 36,064 producer members in ten provinces and services from planting to marketing of cotton, peanut, soybean, sunflower and canola.[68]

Adana Agriculture Fair is the region's largest fair attracting more than 100 thousand visitors from 20 nations. The fair hosts agriculture, livestock, poultry and dairy businesses. Greenhouse and Gardening Fair also takes place at the same time in part of the Agriculture Fair. The fair is organized on a 3.5-hectare area at TÜYAP Exhibition Center every year in October.[69]

Manufacturing

Adana is an industrialized city where large-scale industry is based mostly on agriculture. Food processing and fabricated metal products are the major industries constituting 27 percent of Adana's manufacturing,[70] furniture and rubber/plastic product manufacturing plants are also numerous. As of 2008, Adana has 11 companies in Turkey's top 500 industrial firms.[71] The largest company in Adana, Temsa Global, an automotive manufacturer, has more than 2500 employees and manufactures 4000 buses annually. Marsan-Adana is the largest margarine and plant oil factory in Turkey.[72] Advansa Sasa is Europe's largest polyester manufacturer employing 2650.[73] Organized Industrial Region of Adana has an area of 1225 hectare with 300 plants, mostly medium-scale.

Demographics

As of December 2019, the total population of the four districts is 1,768,860.[74]

The population of the four districts of Adana since 2008 are:

| District | City Population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Seyhan | 752,308 | 722,852 | 723,277 | 757,928 | 764,714 | 779,232 | 788,722 | 797,563 | 800,387 | 793,480 | 796,286 |

| Yüreğir | 411,299 | 415,047 | 417,693 | 421,692 | 416,302 | 419,240 | 419,011 | 419,902 | 424,999 | 415,198 | 414,574 |

| Çukurova | 267,453 | 327,460 | 343,770 | 326,938 | 335,733 | 353,680 | 359,315 | 362,351 | 364,118 | 365,735 | 376,390 |

| Sarıçam | 86,727 | 90,879 | 99,313 | 103,232 | 111,976 | 143,547 | 150,425 | 156,748 | 163,833 | 173,154 | 181,610 |

| Total | 1,517,787 | 1,556,238 | 1,584,053 | 1,609,790 | 1,628,725 | 1,695,699 | 1,717,473 | 1,736,564 | 1,753,337 | 1,747,567 | 1,768,860 |

Two-thirds of the residents of Adana live west of the Seyhan River, where the city was first founded. Urban sprawl east of the river is limited due to large institutions such as Çukurova University and Incirlik Air Base. Seyhan is the most diverse district, accommodating all ethnic groups.

The major ethnic groups in Adana are the Turks, Arabs and Kurds. Population growth slowed between 1885 and 1927 because of the Adana Massacre and the Armenian deportations, with the numbers only being replenished, rather than increased, by refugees brought in from the Balkans and Crete as part of the Population Exchange of 1923. The first Turks moved to the city from Khorosan at the 8th century. In the early 14th century, several Türkmen tribes were settled after Mamluks took control of Çukurova.[75] An Ottoman tax register from 1526 records 16 Turkish residential areas, but only one Armenian and none that were Greek, Jewish, Kurd or Arab.[76] During the 17th century more Armenians and Greeks settled in the city; according to Evliya Çelebi there was also an Arab population.[76]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1885 | 69,266 | — |

| 1908 | 107,450 | +55.1% |

| 1927 | 72,577 | −32.5% |

| 1955 | 100,367 | +38.3% |

| 1980 | 574,515 | +472.4% |

| 2000 | 1,130,710 | +96.8% |

| 2019 | 1,768,860 | +56.4% |

Arabs are concentrated in Karşıyaka quarter of Yüreğir. The demography of the city changed significantly in the 1990s after the massive migration of Kurds, many of them being forced to leave their villages in the southeast at the peak of Turkey–PKK conflict.[77] Kurds mostly live in southern neighborhoods of the city.[78] Conos, a tribe of Romani people of Romania, settled in Adana during the Balkan Wars. Conos mainly live around Sinanpaşa neighborhood. Around 8,000 Romani people live in Adana Province, including Conos.[79] There is a sizeable community of migrants from the Balkans and Caucasia, who also settled in Adana during the Balkan Wars and before.

An estimated 2,000 families of Crypto-Armenians live in Adana, identifying themselves as Arabs, Kurds or Alevis for the last century.[80] In addition, there are a large number of descendants of the Armenian children given to Muslim families to be fostered in 1915, either by their Armenian parents or by Ottoman officials. Christians constituted 45% of the population of Adana before 1915.[81] Most Adana Armenians now live in Buenos Aires, Argentina where they form majority of the Armenian Argentines there.[42]

Adana is home to a community of around 2,000 British and Americans serving at the Incirlik NATO Air Base. Before 2003, the community numbered up to 22,000, but declined when many troops were stationed in Iraq.[82]

Similar to other cities on the Mediterranean and Aegean coasts, secularism is strong in Adana. Among the people with faith, the majority of the residents adhere to Sunni Islam. The majority of Turks, most of the Kurds and some of the Arabs are Sunni Muslim. Adana is also a stronghold of Alevism, many Alevis having moved to the city from Kahramanmaraş after the incidents in 1978. Arabs of Adana are mostly Alawi, which is often confused with Alevis. Alawi Arabs are locally known as Nusayri or Fellah. Arabs from Şanlıurfa Province are Sunni Muslims. There is a tiny community of Roman Catholics and a few Jewish families.

Cityscape

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

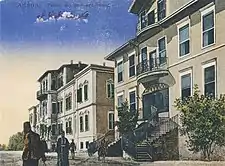

The golden age for the architecture of Adana was the late 15th and 16th centuries when Ramadanid principality chose Adana as their capital. The city grew rapidly during that period with many new neighborhoods being built. Most of the historical landmarks of Adana were built during this period, thus Mamluk and Seljuqid architecture are dominant in Adana's architectural history. Taşköprü is the only remaining landmark from the Roman-Byzantine era, and few public buildings were built during Ottoman rule. Adana is home to modern Turkey's historic Armenian architecture, which can be found behind the city's central modern buildings.

The first traces of settlement in the quarter of Tepebağ, can be traced to the neolithic age. The quarter is next to the Taşköprü stone bridge, situated on a hill which gave its name Tepebağ (Garden on the hill). The city administration has launched a campaign to preserve the heritage of this area, particularly the Ottoman houses. Atatürk stayed in one of these houses on Seyhan Caddesi which now houses the Atatürk Museum.

Several bridges cross the Seyhan river within the city, the most notable among them is the Taşköprü, a 2nd-century Roman bridge.[83] Currently used by pedestrians and cyclists, it was the oldest bridge in the world to be open to motorized vehicles until 2007. Demirköprü is a railway bridge that was built in 1912 as part of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway project. Regülatör bridge, at the southern section of the city, is a road bridge as well as a regulator for the river water. There are also three footbridges, Seyhan and Mustafakemalpaşa road bridges, the bridge of the metro and the bridge of the motorway spanning the river.

Büyük Saat (The Great Clock Tower), built by the local governor of Adana in 1882, is the tallest clock tower in Turkey rising 32 m (104.99 ft) high. It was damaged during French occupation, but was rebuilt in 1935, and its image can be found in the city's coat of arms. Kazancılar Çarşısı (Bazaar of Kazancilar), founded around the Büyük Saat.

Ramazanoğlu Hall was built in 1495 during the reign of Halil Bey. A three-story building, made of stone and brick, it is one of the oldest examples of a house in Turkey. This hall is the Harem section, where the Ramadanid family lived. Selamlık section, where the government offices were, no longer exists.

Çarşı Hamam (Turkish bath of the Bazaar) was built in 1529 by Ramazanoğlu Piri Pasha and it is the largest hamam in Adana. It is built with five domes and the inside is covered with marble. During the time it was built, water was brought from Seyhan River by water wheels and canals.[84]

Irmak Hamam (Turkish bath of the River), located next to Seyhan District Hall, was built in 1494 by Ramazanoğlu Halil Bey on the ruins of an ancient Roman bath. Its water comes from the river. Other historical hamams in the city are Mestenzade Bath and Yeni Bath.

Mosques Sabancı Merkez Camii, though not being historical, is the most visited mosque in Adana, as it is one of the largest mosques in the Middle East. Built in loyalty to Ottoman Architecture, the mosque was opened in 1998 to a capacity of 28,500 prayers. The mosque has six minarets, four of them being 99 meters high. Its dome has a diameter of 32 meters and is 54 meters above the praying area. It is located on the west bank of Seyhan River at the corner of Seyhan Bridge and can be seen from a wide area.[85]

Ulu Cami, a külliye built in 1541 during Ramadanid era, is the most interesting medieval structure of Adana with its mosque, madrasah and türbe. The mosque is of black and white marble with decorative window surrounds and it is famous for the 16th century Iznik tiling used in its inner space. The minaret is unique with the Mamluk effects it bears and with its orthogonal plan scheme.

Yağ Camii was originally built as the Church of St. James, then converted into a mosque by Ramazanoğlu Halil Bey in 1501.[86] His successor Piri Mehmet Paşa added its minaret in 1525 and its madrasah in 1558. It is in the Seljuqid Grand Mosque style and has an attractive gate made of yellow stone.

Yeni Camii (New Mosque) was built in 1724 by Abdülrezzak Antaki, and is still known as Antaki Mosque by some. The influence of Mamluk architecture is visible. It is built in rectangular order and has an interesting stonework on its south walls.[87]

Alemdar Mescidi, Şeyh Zülfi Mescidi, Kızıldağ Ramazanoğlu Mosque, Hasan Aga Camii (16th Century wooden architecture constructed without nails) are some other mosques having historical value.

Churches

In the 19th century, the city had four churches; two Armenian, one Greek and one Catholic. Saint Paul Church (Bebekli Kilise) is a Roman Catholic church that was built in 1870. It is located in the old town, close to 5 Ocak Square and currently serves the Roman Catholic and the Protestant communities.

Agios Nikolaos Greek Orthodox Church was built in 1845 in the Kuruköprü area and was converted into a museum in 1950. The church was restored to its original state and purpose in 2015 and is renamed Kuruköprü Monumental Church.

Armenian Church on Ali Münif Street, at midpoint between Yağ Camii to Büyüksaat, was converted into a Ziraat Bank branch during the Republican Era. Surp Asdvadzadzin Armenian Apostolic Church on the Abidinpaşa Street which served until 1915, was used as a movie theatre until 1970, and then demolished by the government and the Central Bank (Merkez Bankası) regional headquarters was built in its stead.[88]

Parks and gardens

Adana has many parks and gardens.[89] Owing to the warm climate, parks and gardens are open all year long without the need of winter maintenance.

Recreational pathways on both banks of Seyhan river cross the entire city from south end to Seyhan Reservoir. Pathway then connects to Adnan Menderes Boulevard which follows the southern shores of Seyhan Reservoir, and the wide sidewalks of the boulevard extend the pathway to the west end of the reservoir. Dilberler Sekisi is the most scenic part of the pathway which is along the west bank, in between the old and the new dam. Recreational pathway along the north side of the Grand Canal goes from east end to west end of the city, crossing Seyhan river from old dam's pathway. Some sections of this pathway have not yet been completed. Once completed, within the city there will be almost 30 kilometres (19 miles) of continuous recreational pathway connecting several parks.

Merkez Park (Central Park) is a 33-hectare urban park that is located on both banks of Seyhan river, just north of Sabancı Mosque. With a 2100-seater amphitheatre, a Chinese Garden, and two cafes, it is the main recreational area of the city. In the park, there is a Rowing Club which serves recreational rowers.

Süleyman Demirel Arboretum is a large botanical garden containing living collections of woody plants intended partly for the scientific study of Çukurova University researchers. The arboretum is also used for educational and recreational purposes by city residents. 512 species of plants exist in the arboretum.[90]

Atatürk Park is a 4.7-hectare city park built during the first years of the Republic. It is centrally located in the commercial district. The park holds a statue of Atatürk and hosts public ceremonies.

Çobandede Park is a 16.5-hectare park at the west shore of Seyhan Reservoir. It is situated on a hill overlooking the reservoir. The park has the tomb of Çoban Dede, a wise man from Karslı Village.

Yaşar Kemal Woods is a hiking area on the east bank of Seyhan river across Dilberler Sekisi. It is dedicated to Çukurova native writer Yaşar Kemal. Çatalan Woods is a large recreational area between Çatalan and Seyhan reservoirs, north of the city, in the Karaisalı district.

Society and culture

One of the major elements that define the society of Adana is the agriculture-based living and its extension, agriculture-based industrial culture. However, developments in industrial life, improvements in transportation, effects of communication and massive migrations have affected the unique culture of Adana. Similar to other cities in Turkey, the culture in some sections in the city are very distinct from each other.[91]

Cuisine

Adana cuisine is influenced mainly from Yörük, Arabic and Armenian cuisine and the city has kept up its traditions. Spicy, sour and fatty dishes made of meat (usually lamb) and bulghur are common. Bulghur and flour are found in all Çukurova kitchens. In almost every home, red pepper, spices, tahini, a chopping block and pastry board can be found. The bulghur used in cooking is specific to Adana, made from dark colored hard wheat species with a preferred flavor.[92]

Adana Kebab, called "Kebap" locally, is a kebab made from minced meat. Since it can be found at all kebab restaurants in Turkey and at most Turkish restaurants around the world, the Adana name still suggests kebab to many people. Adana Kebab is the most popular dining choice in Adana, although foods from other cultures are becoming increasingly popular. Besides many kebab restaurants, there are also many kebab serving vendors in the older streets of Adana.

Adana Kebab is usually served with onion salad, green salad or with well-chopped tomato salad. Rakı and Şalgam usually accompany it as drinks. There are many varieties of salads typical to the city. Radish salad with tahini is popular and it is found only in the Çukurova region. Şalgam and pickle juice are the drinks of the winter and aşlama (licorice juice) is the choice of drink in summer.

One of the famous sweets of Turkey called "Sweet Sausage" originated from Adana. It was invented by Sir Duran O. during the First World War, around 1915 Seker Sucugu.

Vegetable dishes are also popular in the city. Besides tomato paste, pepper paste is used in almost every dish. The city is also famous for its Şırdan a kind of home-made sausage stuffed with rice, and eaten with cumin; paça, boiled sheep's feet; bicibici (pronounced as bee-jee-bee-jee) made from jellied starch, rose water and sugar is served with crushed ice and consumed especially in summertime. Furthermore, the city has a number of famous desserts, such as Halka Tatlı, a round-shaped dessert, and Taş Kadayıf, a bow-shaped dessert. Several types of fruit, including the apricot, are native to this area.

Arts and entertainment

Performing arts

Çukurova State Symphony Orchestra performed its first concert in 1992 and since then, the orchestra performs twice weekly from October to May at the Metropolitan Theatre Hall. The orchestra consists of 39 musicians and conducts regular tours in Turkey and abroad. Adana State Theater opened its stage in 1981 at the Sabancı Cultural Center. It performs regularly from October to May.[93] Adana Town Theatre was founded in 1880 by governor Ziya Paşa to be the first theater in Adana. In 1926, the theater moved to the newly built Community Center. Town Theatre currently performs weekly at the Metropolitan Theatre Hall and the Ramazanoğlu Center. Seyhan Town Theatre and Seyhan Folkloric Dances are weekly events at the Theater Hall of Seyhan Cultural Center.

Amphitheaters in Adana host performances from April to November. Mimar Sinan Amphitheater, the largest in Adana, can accommodate 8,000 guests and hosts concerts and movies. It is located at the west bank of the Seyhan River. 2,100-seater Merkez Park Amphitheater, 3,000-seater Çukurova University Amphitheater and Doğal Park Amphitheater in Çukurova District also host theaters, concerts and cinemas. Recently, historic buildings have been restored and converted into cultural centers. The 515-year-old Ramazanoğlu Hall and 130-year-old former high school for girls (now called the Adana Center for Arts and Culture) serve as cultural centers hosting art exhibitions and cultural events.

Museums and art galleries

Adana Archaeological Museum was opened in 1924 as one of the oldest ten museums in Turkey. It moved to its current location at the west corner of Seyhan Bridge in 1972. The museum exhibits archeological works from all over Çukurova. Notable works are the two Augustus statues from Hittites, Achilles Sarcophagus depicting Trojan War and statues from Magarsus and Augusta ancient cities.

Adana Ethnography Museum was opened in 1983 after Archeological Museum moved to its new location. In the front and back yard there are epitaphs and gravestones of Adana's leading figures of the 17th century. In the west yard, there are inscriptions of Taşköprü, Misis Bridge, old City Hall and Bahripaşa Fountain. Inside, there are clothing, jewellery and weaponry of Yörük villagemen.

Atatürk Museum exhibits War of Independence and first years of Republic at the mansion where Atatürk stayed during his trips to Adana.

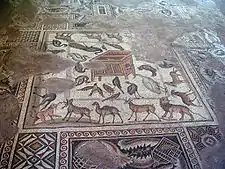

Misis Mosaic Museum, located on the city's far east end at the west bank of Ceyhan river, exhibits mosaics that were on the floor of a 4th-century temple in the ancient city of Misis. The mosaic depicts Noah and 23 birds and poultry that he took onto the ark during the Flood. The museum also exhibits the works that were excavated from Misis Tumulus.[94]

Karacaoğlan Museum of Literature, Adana Museum of Cinema, Yeşiloba Martyrs' Museum, Mehmet Baltacı Museum of Photography and Adana Urban Museum are other noteworthy museums in the city, many of them located in restored historical buildings.[95] State Fine Arts Gallery was opened in Sabancı Cultural Center in 1982. It carries 59 plastic pieces of art. 75.Yıl Art Gallery in Atatürk Park, Adana City Hall Art Gallery and Art Gallery in Seyhan Cultural Center are the other public art galleries.

Festivals

Altın Koza International Film Festival is one of the top film festivals in Turkey, taking place since 1969. During the Altın Koza of 2009, 212 international films were shown in 11 movie theatres across the city. Long Film Contest, International Student Film Contest and Mediterranean Cultures Film Contest are held during the festival.

International Sabancı Theater Festival is held every year in April since 1999. At the festival in 2011, 461 artists from 17 ensembles (10 local and 7 international) performed plays on the stage at the Sabancı Cultural Center. The festival's opening show was staged on the Seyhan River and Taşköprü by Italian ensemble Studio Festi. "Water Symphony" show was greeted by thousands of people with great enthusiasm.[96]

Orange Blossom Carnival is held every April, inspired by the scent coming from the city's orange tree-lined streets. The carnival parade of 2015 attracted more than 90 thousand people—the highest attendance ever in an outdoor event in Adana.[97] Organized concerts and shows in the city's squares, parks and streets are accompanied by spontaneous street celebrations.

International Çukurova Instrumental Music Festival is a two-week long festival held annually in Adana, Antakya and Gaziantep. In 2009, the festival took place for the fifth time with an opening concert from Çukurova State Symphony Orchestra. Baritone Marcin Bronikowski, pianist Vania Batchvarova, guitarist Peter Finger, cellist Ozan Tunca and pianist Zöhrap Adıgüzelzade were some of the musicians who performed at the festival.[98]

Çukurova Art Days is a regional festival that takes place yearly since 2007. In 2012, the festival took place on 22–26 March in Adana, Mersin, Tarsus, Antakya, İskenderun, Silifke, Anamur and Aleppo. There were 94 events including concerts, poetry, exhibitions, talks and conferences.[99]

13 Kare Arts Festival began in 1999 as a festival of photography dedicated to 13 photographers of Adana who died in an accident during an AFAD (Adana Photography Amateurs Association) trip. The festival then expanded to include other arts. During the festival, exhibitions of nature, undersea and architecture photography, puppet shows, shadow theater and several concerts are held. The festival takes place every December.

Adana Literature Festival is held every April at Adana Center for Arts & Culture. Around 100 writers, poets and critics participate in the festival and give talks, make up panels and make presentations.

Nightlife

The city was well known for its vibrant nightlife and many pavyons from the 1950s to the 1980s. Although some were family entertainment places, pavyons mostly functioned as adult entertainment clubs, similar to hostess clubs of Japan, with live music, usually two-storey, a stage and a lounge with tables lined up at the main floor and private rooms at the upper floor.[100] The first pavyons opened in the city by 1942 with the arrival of English workers who worked on the Adana-Ulukışla road that was funded by the British Government to persuade Turkey to form a front in World War II.[101] As Çukurova cotton was valued by the early 1950s, the surplus took landowners to the pavyons which opened more and more along the Seyhan river. In the 1960s, rapid industrialization brought more men to pavyons not only from the city, but from a wide region including Istanbul and Ankara, thus Adana was named Pavyon Capital of Turkey. Many popular singers took the stage at and owe their fame to the pavyons of Adana.

Pavyons led the way to Western-style pubs and night clubs by the late 1980s with the socio-economic changes in Adana. The traditional entertainment district is Sular, near Central Station, but the pubs and clubs nowadays are spread throughout the city. The bigger clubs such as Life Legend, Uptown, Casara and Lava host world star singers at their elegant locations, mostly along the river and the lake. There are still two active pavyons, Afrodit and Maksim, but adult entertainment is directed mostly to what is known locally as tele-bars. Tele-bars are licensed as regular pubs, but function as places where bargirls entertain customers and usually hook with them afterwards. There are around 20 tele-bars mainly in the city center and around the old dam.[102]

A hundred-year-long tradition of kebab, liver and rakı in the Kazancılar Bazaar, with street music and dances, turned into a festival since 2010, with all-night entertainment. World Rakı Festival, held the second Saturday night of December, attracts more than 20 thousand people to the old town.[103]

Sports

_STADI.jpg.webp)

Athletic sport life progressed in Cilicia in the early 20th century with the coaches that were invited to Adana from Istanbul. Varag Pogharian and Mateos Zarifian played an important role in the organization of the athletic movement and the first sports clubs in the city were founded by the Armenian community. Adana Türkgücü were founded in 1913 by Ahmet Remzi Bey and İsmail Sefa Bey in alliance with the Istanbul Türkgücü club that is initiated by the Committee of Union and Progress.[104] Athletic clubs of Adana joined the Cilician Olympic Games that were held in April 1914 at a venue north of Dörtyol, first of its kind in the region.[105] Adana İdman Yurdu, Adana Türk Ocağı, Seyhanspor and Milli Mensucat clubs were founded in the city in the 1920s, all joining the Adana Football League that was established in 1924 with the clubs from other Cilician provinces. Adanaspor that were founded in 1932 and Adana Demirspor that were founded in 1940, later on joined the Çukurova League.

Football is the most popular sport in Adana; basketball, volleyball and handball are also played widely at professional and amateur levels. Warm weather make the city a haven for sports like rowing, sailing, swimming and water polo. Horse racing and horse riding are also popular. Bi-annual Men's European Wheelchair Basketball Championship took place in Adana on 5–15 October 2009. Twelve countries competed at the event and Italy won the title after a final game against Turkey.[106] Adana also hosted the 2013 IWBF Men's U23 Wheelchair Basketball World Championship.[107] 1967 Women's European Volleyball Championship was organized in Turkey and Adana was a host city together with Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir. Group C games are played in Adana at the Menderes Sports Hall.[108]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adanaspor | Football (men) | TFF First League | 5 Ocak Stadium (14,805) | 1954 |

| Adana Demirspor | Football (men) | TFF First League | 5 Ocak Stadium (14,805) | 1940 |

| Adana İdmanyurdu | Football (women) | First Football League | Gençlik Stadium (2000) | 1993 |

| Kiremithanespor | Football (men) | Turkish Regional Amateur League | Kaynak Kardeşler Stadium (2000) | 1979 |

| Adana Basketbol Kulübü | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Atatürk Sports Hall (2000) | 2000 |

| Adanaspor | Basketball (men) | Basketball Second League | Menderes Sports Hall (2000) | 2006 |

| ABB Şakirpaşa | Handball (women) | Women's Super League | Yüreğir Serinevler Arena (2000) | 2012 |

Adanaspor and Adana Demirspor are the two clubs of Adana that appear in Turkish Professional Football League. After 12 years, Adanaspor returned to Super Lig,[109] in which they had competed for 21 years and were the runner up in 1980–81 season. Adanaspor also performed at the UEFA Cup for three years. Adana Demirspor, currently performing at the TFF First League, was the runner up at the Turkish Cup in 1977–1978 season and performed at the SuperLig for 17 years. Both teams share 5 Ocak Stadium as their venue, and the matches between them are known as the Adana derby, an archrival atmosphere that is found in only three cities in Turkey. Kiremithanespor of the Yüreğir district, compete at the Turkish Regional Amateur League. In women's football, Adana İdmanyurduspor competes in the First Football League, and plays their home games at the Gençlik Stadium.

Adana ASKİ are the major clubs in Women's Pro-Basketball—both performing in the Turkish Women's Basketball League (TKBL). Adana ASKİ was founded in Ceyhan in 2000, under the name 'Ceyhan Belediyespor', and renamed and moved to Adana in 2014. After the move, the club performed the best season ever (2014–15), playing in the final at the Turkish Women's Cup and semi-final at the TKBL First Division. Adana ASKİ also play their home games at Menderes Sports Hall. Adanaspor, relegated to the third tier of the Turkish Men's Basketball League in 2016,[110] playing their home games at the Menderes Sports Hall. Wheelchair basketball clubs, Adana Engelliler and Martı Engelliler appear in the first division of the Turkish Wheelchair Basketball League, both playing their home games at the Serinevler Sports Hall.

Professional volleyball club Adana Toros was promoted to the top flight of the Turkish Men's Volleyball League on 12 April 2016 at the play-off finals in Bursa.[111] Adana Toros play their homes games at the Menderes Sports Hall.[112] The city's handball club, Şakirpaşa HEM, promoted to the Turkish Women's Handball Super League on 21 April 2016, at the play-off finals in Ankara.[113] The venue of Şakirpaşa is Yüreğir Serinevler Arena.[114]

Water sports have been recreationally and competitively the traditional sports of Adana. Water polo team of Adana Demirspor is a legend in the community, joining the Turkish Waterpolo League in 1942 after the first modern water sport venue of Turkey, Atatürk Swimming Complex, opened in Adana in 1936. The team has a record 22 years of straight championship title in Turkish Men's Waterpolo League, 17 years of it without losing a game and thus their given name "Unbeatables". Demirspor has a total of 29 championship titles.[115] Rowing became a popular sport in Adana in the last 20 years. Rowing competitions are held all year long on Seyhan River and Seyhan Reservoir. Metropolitan Rowing Club and Çukurova University SK compete at national and international level. Sailing competitions[116] are also held at Seyhan Reservoir all year long. Adana Sailing Club performs at sailing competitions in different categories. In swimming, Erdal Acet of Adana Demirspor is a prominent figure in Adana, who broke the record of swimming Canal La Manche (English Channel) in 9 hours and 2 minutes in 1976. Recreationally, the lack of swimming pools made Seyhan River and the irrigation canals attractive for swimmers who want to cool off from the hot and humid summers. Due to almost 100 people suffocating every year, the Metropolitan Municipality built and opened 41 swimming pools over the last 15 years.[117]

Adana Half Marathon was inaugurated in 2011 on a national level with the participation of 223 athletes. In 2012, the marathon gained IAAF International Marathon status and hosted 610 athletes from 10 nations.[118] The marathon takes place on the first Sunday following 5 January, Adana's independence day. Master Men, Master Women and Wheelchair competitions, as well as 4 kilometres (2 miles) Public Run are held during the event. The racecourse follows the historic streets of Adana and the streets along the Seyhan river.[119]

Adana is one of the cities of Turkey where horse racing is highly popular. Yeşiloba Hippodrome is traditionally one of the four race courses of Turkey, hosting horse racing competitions from October to May. Adana Equestrian Club is the largest center of horse riding in Turkey, hosting national and international competitions.

Contemporary life

Media

Media in Adana runs by national and local agencies. Çukurova Journalists Union is the umbrella organization for the local media in the region.

There are several newspapers published daily in Adana, the most popular ones being the Yeni Adana, Ekspres, Toros, Bölge and 5 Ocak papers. Yeni Adana is the oldest newspaper and dates back to 1918.[120] The newspaper played a significant role in the independence movement after the First World War. Most newspapers in Adana serve not only the city but the Çukurova region. Many national newspapers have their regional publishing centers in Adana. Hürriyet publishes a supplement paper, Hürriyet Çukurova, the most popular regional newspaper, that has circulation of 48,000. Sabah's regional supplement paper, Güney, is also published in Adana.

Kanal A is the longest serving TV broadcaster in Adana, Çukurova TV, Akdeniz TV, Koza TV and Kent TV are the other major broadcasters. There are numerous local radio channels and TRT's Çukurova Radio can be listened to in the city.

Shopping

Çakmak Street is the traditional shopping street that is located in the old town. Several attempts by the city to designate it as a pedestrianised street was unsuccessful because traffic flow could not be diverted to another street. There are several historical bazaars around Büyük Saat and Yağ Camii. Covered markets around Saydam street, Kilis and Mısır bazaars, were once a haven for shopping for quality foreign goods.