Turnover (employment)

In the context of human resources, turnover is the act of replacing an employee with a new employee. Partings between organizations and employees may consist of termination, retirement, death, interagency transfers, and resignations.[1] An organization’s turnover is measured as a percentage rate, which is referred to as its turnover rate. Turnover rate is the percentage of employees in a workforce that leave during a certain period of time. Organizations and industries as a whole measure their turnover rate during a fiscal or calendar year.[1]

If an employer is said to have a high turnover rate relative to its competitors, it means that employees of that company have a shorter average tenure than those of other companies in the same industry. High turnover may be harmful to a company's productivity if skilled workers are often leaving and the worker population contains a high percentage of novices. Companies will often track turnover internally across departments, divisions, or other demographic groups, such as turnover of women versus men. Additionally, companies track voluntary turnover more accurately by presenting parting employees with surveys, thus identifying specific reasons as to why they may be choosing to resign. Many organizations have discovered that turnover is reduced significantly when issues affecting employees are addressed immediately and professionally. Companies try to reduce employee turnover rates by offering benefits such as paid sick days, paid holidays and flexible schedules.[2] In the United States, the average total of non-farm seasonally adjusted monthly turnover was 3.3% for the period from December, 2000 to November, 2008.[3] However, rates vary widely when compared over different periods of time and with different job sectors. For example, during the 2001-2006 period, the annual turnover rate for all industry sectors averaged 39.6% prior to seasonal adjustments,[4] while the Leisure and Hospitality sector experienced an average annual rate of 74.6% during this same period.[5] External factors, such as financial needs and work-family balances due to environmental changes (e.g. economic crisis), can also lead to increased turnover rate.[6]

Varieties

There are four types of turnovers: Voluntary is the first type of turnover, which occurs when an employee voluntarily chooses to resign from the organization. Voluntary turnover could be the result of a more appealing job offer, staff conflict, or lack of advancement opportunities.[1]

The second type of turnover is involuntary, which occurs when the employer makes the decision to discharge an employee and the employee unwillingly leaves his or her position.[1] Involuntary turnover could be a result of poor performance, staff conflict, an at-will employment clause, etc.

The third type of turnover is functional, which occurs when a low-performing employee leaves the organization.[1] Functional turnover reduces the amount of paperwork that a company must file in order to rid itself of a low-performing employee. Rather than having to go through the potentially difficult process of proving that an employee is inadequate, the company simply respects his or her own decision to leave.

The fourth type of turnover is dysfunctional, which occurs when a high-performing employee leaves the organization.[1] Dysfunctional turnover can be potentially costly to an organization, and could be the result of a more appealing job offer or lack of opportunities in career advancement. Too much turnover is not only costly, but it can also give an organization a bad reputation. However, there is also good turnover, which occurs when an organization finds a better fit with a new employee in a certain position. Good turnover can also transpire when an employee has outgrown opportunities within a certain organization and must move forward with his or her career in a new organization.[7]

Turnover as with the non resolution of an employee asset issue (E.g. Cyber : Opportunity & risk) and their course of work in the digital era.

Costs

When accounting for the costs (both real costs, such as time taken to select and recruit a replacement, and also opportunity costs, such as lost productivity), the cost of employee turnover to for-profit organizations has been estimated to be between 30% (the figure used by the American Management Association) to upwards of 150% of the employees' remuneration package.[8] There are both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs relate to the leaving costs, replacement costs and transitions costs, and indirect costs relate to the loss of production, reduced performance levels, unnecessary overtime and low morale. The true cost of turnover is going to depend on a number of variables including ease or difficulty in filling the position and the nature of the job itself. Estimating the costs of turnover within an organization can be a worthwhile exercise, especially since “turnover costs” are unlikely to appear in an organization’s balance sheets. Some of the direct costs can be readily calculated, while the indirect costs can often be more difficult to determine and may require “educated guesses.” Nevertheless, calculating even a rough idea of the total expenses relating to turnover can spur action planning within an organization to improve the work environment and reduce turnover. Surveying employees at the time they leave an organization can also be an effective approach to understanding the drivers of turnover within a particular organization.[9]

In a healthcare context, staff turnover has been associated with worse patient outcomes.[10]

Internal versus external

Like recruitment, turnover can be classified as "internal" or "external".[11] Internal turnover involves employees leaving their current positions and taking new positions within the same organization. Both positive (such as increased morale from the change of task and supervisor) and negative (such as project/relational disruption, or the Peter Principle) effects of internal turnover exist, and therefore, it may be equally important to monitor this form of turnover as it is to monitor its external counterpart. Internal turnover might be moderated and controlled by typical HR mechanisms, such as an internal recruitment policy or formal succession planning.

Internal turnover, called internal transfers, is generally considered an opportunity to help employees in their career growth while minimizing the more costly external turnover. A large amount of internal transfers leaving a particular department or division may signal problems in that area unless the position is a designated stepping stone position.

Skilled vs. unskilled employees

Unskilled positions often have high turnover, and employees can generally be replaced without the organization or business incurring any loss of performance. The ease of replacing these employees provides little incentive to employers to offer generous employment contracts; conversely, contracts may strongly favour the employer and lead to increased turnover as employees seek, and eventually find, more favorable employment.

Voluntary versus involuntary

Practitioners can differentiate between instances of voluntary turnover, initiated at the choice of the employee, and involuntary turnover initiated by the employer due to poor performance or reduction in force (RIF).

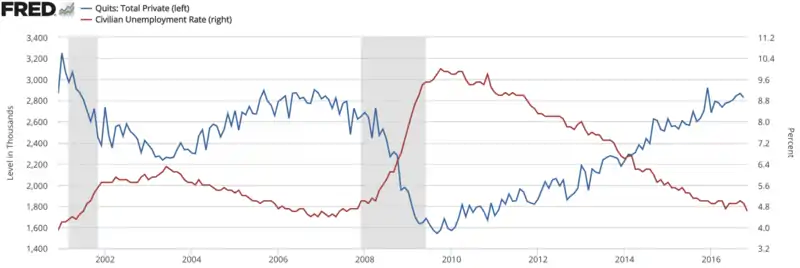

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics uses the term "Quits" to mean voluntary turnover and "Total Separations" for the combination of voluntary and involuntary turnover.

Causes of high or low turnover

High turnover often means that employees are dissatisfied with their jobs, especially when it is relatively easy to find a new one.[12] It can also indicate unsafe or unhealthy conditions, or that too few employees give satisfactory performance (due to unrealistic expectations, inappropriate processes or tools, or poor candidate screening). The lack of career opportunities and challenges, dissatisfaction with the job-scope or conflict with the management have been cited as predictors of high turnover.

Each company has its own unique turnover drivers so companies must continually work to identify the issues that cause turnover in their company. Further the causes of attrition vary within a company such that causes for turnover in one department might be very different from the causes of turnover in another department. Companies can use exit interviews to find out why employees are leaving and the problems they encountered in the workplace.

Low turnover indicates that none of the above is true: employees are satisfied, healthy and safe, and their performance is satisfactory to the employer. However, the predictors of low turnover may sometimes differ than those of high turnover. Aside from the fore-mentioned career opportunities, salary, corporate culture, management's recognition, and a comfortable workplace seem to impact employees' decision to stay with their employer.

Many psychological and management theories exist regarding the types of job content which is intrinsically satisfying to employees and which, in turn, should minimise external voluntary turnover. Examples include Herzberg's two factor theory, McClelland's Theory of Needs, and Hackman and Oldham's Job Characteristics Model.[13]

Stress

Evidence suggests that distress is the major cause of turnover in organizations.[14]

Bullying

A number of studies report a positive relationship between bullying, intention to leave and high turnover. In some cases, the number people who actually leave is a “tip of the iceberg”. Many more who remain have considered leaving. In O’Connell et al.’s (2007) Irish study, 60% of respondents considered leaving whilst 15% actually left the organisation.[15] In a study of public-sector union members, approximately one in five workers reported having considered leaving the workplace as a result of witnessing bullying taking place. Rayner explained these figures by pointing to the presence of a climate of fear in which employees considered reporting to be unsafe, where bullies had “got away with it” previously despite management knowing of the presence of bullying.[15]

One can rather easily spot an office with a bullying problem - there is an exceptionally high rate of turnover. While not all places with high personnel turnover are sites of workplace bullying, nearly every place that has a bully in charge will have elevated staff turnover and absenteeism.[16]

Narcissism and psychopathy

According to Thomas, there tends to be a higher level of stress with people who work or interact with a narcissist, which in turn increases absenteeism and staff turnover.[17] Boddy finds the same dynamic where there is a corporate psychopath in the organisation.[18]

Investments

Low turnover may indicate the presence of employee "investments" (also known "side bets")[19] in their position: certain may be enjoyed while the employee remains employed with the organization, which would be lost upon resignation (e.g., health insurance, discounted home loans, redundancy packages). Such employees would be expected to demonstrate lower intent to leave than if such "side bets" were not present.

Perceptions of injustice and unfairness

Research suggests that organizational justice plays a significant role in an employee’s intention to exit an organization. Perceptions of fairness are antecedents and determinants of turnover intention, especially in how employees are treated, outcomes are distributed fairly, and processes and procedures are consistently followed.[20]

Prevention

Employees are important in any running of a business; without them the business would be unsuccessful. However, more and more employers today are finding that employees remain for approximately 23 to 24 months, according to the 2006 Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Policy Foundation states that it costs a company an average of $15,000 per employee, which includes separation costs, including paperwork, unemployment; vacancy costs, including overtime or temporary employees; and replacement costs including advertisement, interview time, relocation, training, and decreased productivity when colleagues depart. Providing a stimulating workplace environment, which fosters happy, motivated and empowered individuals, lowers employee turnover and absentee rates.[21] Promoting a work environment that fosters personal and professional growth promotes harmony and encouragement on all levels, so the effects are felt company wide.[21]

Continual training and reinforcement develops a work force that is competent, consistent, competitive, effective and efficient.[21] Beginning on the first day of work, providing the individual with the necessary skills to perform their job is important.[22] Before the first day, it is important the interview and hiring process expose new hires to an explanation of the company, so individuals know whether the job is their best choice.[23] Networking and strategizing within the company provides ongoing performance management and helps build relationships among co-workers.[23] It is also important to motivate employees to focus on customer success, profitable growth and the company well-being .[23] Employers can keep their employees informed and involved by including them in future plans, new purchases, policy changes, as well as introducing new employees to the employees who have gone above and beyond in meetings.[23] Early engagement and engagement along the way, shows employees they are valuable through information or recognition rewards, making them feel included.[23]

When companies hire the best people, new talent hired and veterans are enabled to reach company goals, maximizing the investment of each employee.[23] Taking the time to listen to employees and making them feel involved will create loyalty, in turn reducing turnover allowing for growth.[24]

Calculation

Labour turnover is equal to the number of employees leaving, divided by the average total number of employees (in order to give a percentage value). The number of employees leaving and the total number of employees are measured over one calendar year.

Where:

- NELDY = Number of Employees who Left During the Year

- NEBY = Number of Employees at the Beginning of the Year

- NEEY = Number of Employees at the End of the Year

For example, at the start of the year a business had 40 employees, but during the year 9 staff resigned with 2 new hires, thus leaving 33 staff members at the end of the year. Hence this year's turnover is 25%. This is derived from, (9/((40+33)/2)) = 25%. However the above formula should be applied with caution if data is grouped. For example, if attrition rate is calculated for Employees with tenure 1 to 4 years, above formula may result artificially inflated attrition rate as employees with tenure more than 4 years are not counted in the denominator.

More precise calculations of turnover have also been developed. For example, instead of averaging the headcounts from the beginning of the year and the end of the year, we can calculate the denominator of Labour Turnover by averaging the headcount from each day of the year. An even better approach is to avoid the several issues inherent to traditional labour turnover rates[25] by employing more advanced and accurate methods (e.g., event history analysis,[26] realized turnover rates[25]).

Models

Over the years there have been thousands of research articles exploring the various aspects of turnover,[27] and in due course several models of employee turnover have been promulgated. The first model, and by far the one attaining most attention from researchers, was put forward in 1958 by March & Simon. After this model there have been several efforts to extend the concept. Since 1958 the following models of employee turnover have been published.

- March and Simon (1958) Process Model of Turnover

- Porter & Steers (1973) Met Expectations Model

- Price (1977) Causal Model of Turnover

- Mobley (1977) Intermediate Linkages Model

- Hom and Griffeth (1991) Alternative Linkages Model of Turnover

- Whitmore (1979) Inverse Gaussian Model for Labour Turnover

- Steers and Mowday (1981) Turnover Model

- Sheridan & Abelson (1983) Cusp Catastrophe Model of Employee Turnover

- Jackofsky (1984) Integrated Process Model

- Lee et al. (1991) Unfolding Model of Voluntary Employee Turnover[28]

- Aquino et al. (1997) Referent Cognitions Model

- Mitchell & Lee (2001) Job Embeddedness Model

References

- Trip, R. (n.d.). Turnover-State of Oklahoma Website. Retrieved from www.ok.gov: http://www.ok.gov/opm/documents/Employee%20Turnover%20Presentation.ppt

- Beam, J. (2014, December 25). What is Employee Turnover? Retrieved from WiseGeek: http://www.wisegeek.org/what-is-employee-turnover.htm

- "Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey". Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, total non-farming separations (not seasonally adjusted), Series ID JTU00000000TSR, http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?jt " Openings and Labor Turnover Survey"

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, total separations Leisure and Hospitality (not seasonally adjusted), Series ID JTU70000000TSR, http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?jt "Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey"

- Wynen, Jan; Op de Beeck, Sophie (2014-07-02). "The Impact of the Financial and Economic Crisis on Turnover Intention in the U.S. Federal Government". Public Personnel Management. 43 (4): 565–585. doi:10.1177/0091026014537043. ISSN 0091-0260.

- Academy, A. B. (Director). (2013). Episode 128: The Different Types of Employee Turnover [Motion Picture].

- Schlesinger, Leonard A.; James L. Heskett (1991-04-15). "Breaking the Cycle of Failure in Services". MIT Sloan Management Review. 33 (3): 17–28. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- The True Costs of Turnover http://www.insightlink.com/blog/calculating-the-cost-of-employee-turnover.cfm

- Williams ACdeC, Potts HWW (2010). Group membership and staff turnover affect outcomes in group CBT for persistent pain. Pain, 148(3), 481-6

- Ruby, Allen M. (January 2002). "Internal Teacher Turnover in Urban Middle School Reform". Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk. 7 (4): 379–406. doi:10.1207/S15327671ESPR0704_2.

- Carsten, J. M.; Spector, P. E. (1987). "Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: A meta-analytic test of the Muchinsky model". Journal of Applied Psychology. 72 (3): 374–381. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.72.3.374.

- Hackman, J. Richard; Greg R. Oldham (August 1976). "Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory". Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 16 (2): 250–279. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7.

- NIOSH (1999). Stress at Work. U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Number 99-101.

- Helge H, Sheehan MJ, Cooper CL, Einarsen S "Organisational Effects of Workplace Bullying" in Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice (2010)

- Robert Killoren (2014) The Toll of Workplace Bullying - Research Management Review, Volume 20, Number 1

- Thomas D Narcissism: Behind the Mask (2010)

- Boddy, C. R. Corporate Psychopaths: Organizational Destroyers (2011)

- Tett, Robert P; John P. Meyer (1993). "Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intention, and Turnover: Path Analyses Based on Meta-Analytic Findings". Personnel Psychology. 46 (2): 259–293. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- DeConinck, James B; C. Dean Stilwell (2004). "Incorporating Organizational Justice, Role States, Pay Satisfaction and Supervisor Satisfaction in a Model of Turnover Intentions". Journal of Business Research. 57 (3): 225–231. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00289-8.

- Employee Pride Goes Wide. (2005, February 2). Graphic Arts Monthly, Retrieved February 23, 2009, from Academic Search Premier database.

- Costello, D. (2006, December). Leveraging the Employee Life Cycle. CRM Magazine, 10(12), 48-48. Retrieved February 23, 2009, from Academic Search Premier database.

- Testa, B (2008). "Early Engagement, Long Relationship?". Workforce Management. 87 (15): 27–31.

- Skabelund, J (2008). "I just work here". American Fitness. 26 (3): 42.

- Stanek, Kevin C. (September 2019). "Starting with the basics: Getting turnover rates right". Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 12 (3): 314–319. doi:10.1017/iop.2019.52. ISSN 1754-9426.

- McCloy, Rodney A.; Purl, Justin D.; Banjanovic, Erin S. (September 2019). "Turnover modeling and event history analysis". Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 12 (3): 320–325. doi:10.1017/iop.2019.56. ISSN 1754-9426.

- Morrell, K. Loan-Clarke J. and Wilkinson A. (2001) Unweaving leaving: The use of models in the management of employee turnover, International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(3), 219-244.

- Lee, T. H.; Gerhart, B.; Weller, I.; Trevor, C. O. (2008). "Understanding voluntary turnover: Path-specific job satisfaction effects and the importance of unsolicited job offers". Academy of Management Journal. 51 (4): 651–671. doi:10.5465/amr.2008.33665124.