Employment

Employment is a relationship between two parties, usually based on contract where work is paid for, where one party, which may be a corporation, for profit, not-for-profit organization, co-operative or other entity is the employer and the other is the employee.[1] Employees work in return for payment, which may be in the form of an hourly wage, by piecework or an annual salary, depending on the type of work an employee does or which sector they are working in. Employees in some fields or sectors may receive gratuities, bonus payment or stock options. In some types of employment, employees may receive benefits in addition to payment. Benefits can include health insurance, housing, disability insurance or use of a gym. Employment is typically governed by employment laws, organisation or legal contracts.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labor |

|---|

|

Employees and employers

An employee contributes labor and expertise to an endeavor of an employer or of a person conducting a business or undertaking (PCB)[2] and is usually hired to perform specific duties which are packaged into a job. In a corporate context, an employee is a person who is hired to provide services to a company on a regular basis in exchange for compensation and who does not provide these services as part of an independent business.[3]

An issue that arises in most companies, especially the ones that are in the gig economy, is the classification of workers. A lot of workers that fulfill gigs are often hired as independent contractors.

As a general principle of employment law, in the United States, there is a difference between an agent and an independent contractor. The default status of a worker is employee unless specific guidelines are met, which can be determined by the ABC test.[4] Thus, clarifying whether someone who performs work is an independent contractor or an employee from the beginning, and treating them accordingly, can save a company from trouble later on.

Provided key circumstances, including ones such as that the worker is paid regularly, follows set hours of work, is supplied with tools from the employer, is closely monitored by the employer, acting on behalf of the employer, only works for one employer at a time, they are considered an employee,[5] and the employer will generally be liable for their actions and be obliged to give them benefits.[6] In order to stay protected and avoid lawsuits, an employer has to be aware of that distinction.

Employer–worker relationship

Employer and managerial control within an organization rests at many levels and has important implications for staff and productivity alike, with control forming the fundamental link between desired outcomes and actual processes. Employers must balance interests such as decreasing wage constraints with a maximization of labor productivity in order to achieve a profitable and productive employment relationship.

Labor acquisition / hiring

The main ways for employers to find workers and for people to find employers are via jobs listings in newspapers (via classified advertising) and online, also called job boards. Employers and job seekers also often find each other via professional recruitment consultants which receive a commission from the employer to find, screen and select suitable candidates. However, a study has shown that such consultants may not be reliable when they fail to use established principles in selecting employees.[1] A more traditional approach is with a "Help Wanted" sign in the establishment (usually hung on a window or door[7] or placed on a store counter).[3] Evaluating different employees can be quite laborious but setting up different techniques to analyze their skill to measure their talents within the field can be best through assessments. Employer and potential employee commonly take the additional step of getting to know each other through the process of job interview.

Training and development

Training and development refers to the employer's effort to equip a newly hired employee with the necessary skills to perform at the job, and to help the employee grow within the organization. An appropriate level of training and development helps to improve employee's job satisfaction.[8]

Remuneration

There are many ways that employees are paid, including by hourly wages, by piecework, by yearly salary, or by gratuities (with the latter often being combined with another form of payment). In sales jobs and real estate positions, the employee may be paid a commission, a percentage of the value of the goods or services that they have sold. In some fields and professions (e.g., executive jobs), employees may be eligible for a bonus if they meet certain targets. Some executives and employees may be paid in stocks or stock options, a compensation approach that has the added benefit, from the company's point of view, of helping to align the interests of the compensated individual with the performance of the company.

Under the faithless servant doctrine, a doctrine under the laws of a number of states in the United States, and most notably New York State law, an employee who acts unfaithfully towards his employer must forfeit all of the compensation he received during the period of his disloyalty.[9][10][11][12][13]

Employee benefits

Employee benefits are various non-wage compensation provided to employees in addition to their wages or salaries. The benefits can include: housing (employer-provided or employer-paid), group insurance (health, dental, life etc.), disability income protection, retirement benefits, daycare, tuition reimbursement, sick leave, vacation (paid and non-paid), social security, profit sharing, funding of education, and other specialized benefits. In some cases, such as with workers employed in remote or isolated regions, the benefits may include meals. Employee benefits can improve the relationship between employee and employer and lowers staff turnover.[14]

Organizational justice

Organizational justice is an employee's perception and judgement of employer's treatment in the context of fairness or justice. The resulting actions to influence the employee-employer relationship is also a part of organizational justice.[14]

Workforce organizing

Employees can organize into trade or labor unions, which represent the work force to collectively bargain with the management of organizations about working, and contractual conditions and services.[15]

Ending employment

Usually, either an employee or employer may end the relationship at any time, often subject to a certain notice period. This is referred to as at-will employment. The contract between the two parties specifies the responsibilities of each when ending the relationship and may include requirements such as notice periods, severance pay, and security measures.[15] In some professions, notably teaching, civil servants, university professors, and some orchestra jobs, some employees may have tenure, which means that they cannot be dismissed at will. Another type of termination is a layoff.

Wage labor

Wage labor is the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer, where the worker sells their labor under a formal or informal employment contract. These transactions usually occur in a labor market where wages are market determined.[8][14] In exchange for the wages paid, the work product generally becomes the undifferentiated property of the employer, except for special cases such as the vesting of intellectual property patents in the United States where patent rights are usually vested in the original personal inventor. A wage laborer is a person whose primary means of income is from the selling of his or her labor in this way.[15]

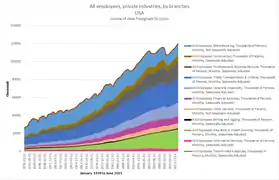

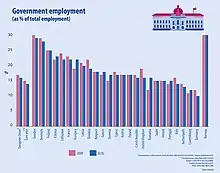

In modern mixed economies such as that of the OECD countries, it is currently the dominant form of work arrangement. Although most work occurs following this structure, the wage work arrangements of CEOs, professional employees, and professional contract workers are sometimes conflated with class assignments, so that "wage labor" is considered to apply only to unskilled, semi-skilled or manual labor.[16]

Wage slavery

Wage labor, as institutionalized under today's market economic systems, has been criticized,[15] especially by both mainstream socialists and anarcho-syndicalists,[16][17][18][19] using the pejorative term wage slavery.[20][21] Socialists draw parallels between the trade of labor as a commodity and slavery. Cicero is also known to have suggested such parallels.[22]

The American philosopher John Dewey posited that until "industrial feudalism" is replaced by "industrial democracy", politics will be "the shadow cast on society by big business".[23] Thomas Ferguson has postulated in his investment theory of party competition that the undemocratic nature of economic institutions under capitalism causes elections to become occasions when blocs of investors coalesce and compete to control the state plus cities.[24]

Employment contract

Australia

Australian employment has been governed by the Fair Work Act since 2009.[25]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh Association of International Recruiting Agencies (BAIRA) is an association of national level with its international reputation of co-operation and welfare of the migrant workforce as well as its approximately 1200 members agencies in collaboration with and support from the Government of Bangladesh.[16]

Canada

In the Canadian province of Ontario, formal complaints can be brought to the Ministry of Labour. In the province of Quebec, grievances can be filed with the Commission des normes du travail.[19]

Pakistan

Pakistan has no contract Labor, Minimum Wage and Provident Funds Acts. Contract labor in Pakistan must be paid minimum wage and certain facilities are to be provided to labor. However, the Acts are not yet fully implemented.[16]

India

India has Contract Labor, Minimum Wage, Provident Funds Act and various other acts to comply with. Contract labor in India must be paid minimum wage and certain facilities are to be provided to labor. However, there is still a large amount of work that remains to be done to fully implement the Act.[19]

Philippines

In the Philippines, employment is regulated by the Department of Labor and Employment.[26]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, employment contracts are categorized by the government into the following types:[27]

- Fixed-term contract: last for a certain length of time, are set in advance, end when a specific task is completed, ends when a specific event takes place.

- Full-time or part-time contract: has no defined length of time, can be terminated by either party, is to accomplish a specific task, specified number of hours.[26]

- Agency staff

- Freelancers, Consultants and Contractors

- Zero-hour contracts

United States

For purposes of U.S. federal income tax withholding, 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) provides a definition for the term "employee" specific to chapter 24 of the Internal Revenue Code:

"For purposes of this chapter, the term “employee” includes an officer, employee, or elected official of the United States, a State, or any political subdivision thereof, or the District of Columbia, or any agency or instrumentality of any one or more of the foregoing. The term “employee” also includes an officer of a corporation."[28] This definition does not exclude all those who are commonly known as 'employees'. “Similarly, Latham’s instruction which indicated that under 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) the category of ‘employee’ does not include privately employed wage earners is a preposterous reading of the statute. It is obvious that within the context of both statutes the word ‘includes’ is a term of enlargement not of limitation, and the reference to certain entities or categories is not intended to exclude all others.”[29]

Employees are often contrasted with independent contractors, especially when there is dispute as to the worker's entitlement to have matching taxes paid, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance benefits. However, in September 2009, the court case of Brown v. J. Kaz, Inc. ruled that independent contractors are regarded as employees for the purpose of discrimination laws if they work for the employer on a regular basis, and said employer directs the time, place, and manner of employment.[26]

In non-union work environments, in the United States, unjust termination complaints can be brought to the United States Department of Labor.[30]

Labor unions are legally recognized as representatives of workers in many industries in the United States. Their activity today centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and electioneering at the state and federal level.[26]

Most unions in America are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL-CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.[24]

American business theorist Jeffrey Pfeffer posits that contemporary employment practices and employer commonalities in the United States, including toxic working environments, job insecurity, long hours and increased performance pressure from management, are responsible for 120,000 excess deaths annually, making the workplace the fifth leading cause of death in the United States.[31]

Sweden

According to Swedish law,[32] there are three types of employment.

- Test employment (swe: Provanställning), where the employer hires a person for a test period of 6 months maximum. The employment can be ended at any time without giving any reason. This type of employment can be offered only once per employer and in employee combination. Usually, a time limited or normal employment is offered after a test employment.[33]

- Time limited employment (swe: Tidsbegränsad anställning). The employer hires a person for a specified time. Usually, they are extended for a new period. Total maximum two years per employer and employee combination, then it automatically counts as a normal employment.

- Normal employment (swe: Tillsvidareanställning / Fast anställning), which has no time limit (except for retirement etc.). It can still be ended for two reasons: personal reason, immediate end of employment only for strong reasons such as crime, or lack of work tasks (swe: Arbetsbrist), cancellation of employment, usually because of bad income for the company. There is a cancellation period of 1–6 months, and rules for how to select employees, basically those with shortest employment time shall be cancelled first.[33]

There are no laws about minimum salary in Sweden. Instead, there are agreements between employer organizations and trade unions about minimum salaries, and other employment conditions.

There is a type of employment contract which is common but not regulated in law, and that is Hour employment (swe: Timanställning), which can be Normal employment (unlimited), but the work time is unregulated and decided per immediate need basis. The employee is expected to be answering the phone and come to work when needed, e.g. when someone is ill and absent from work. They will receive salary only for actual work time and can in reality be fired for no reason by not being called anymore. This type of contract is common in the public sector.[33]

Age-related issues

Younger age workers

Young workers are at higher risk for occupational injury and face certain occupational hazards at a higher rate; this is generally due to their employment in high-risk industries. For example, in the United States, young people are injured at work at twice the rate of their older counterparts.[35] These workers are also at higher risk for motor vehicle accidents at work, due to less work experience, a lower use of seat belts, and higher rates of distracted driving.[36][37] To mitigate this risk, those under the age of 17 are restricted from certain types of driving, including transporting people and goods under certain circumstances.[36]

High-risk industries for young workers include agriculture, restaurants, waste management, and mining.[35][36] In the United States, those under the age of 18 are restricted from certain jobs that are deemed dangerous under the Fair Labor Standards Act.[36]

Youth employment programs are most effective when they include both theoretical classroom training and hands-on training with work placements.[38]

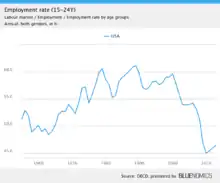

In the conversation of employment among younger aged workers, youth unemployment has also been monitored. Youth unemployment rates tend to be higher than the adult rates in every country in the world.

Older age workers

Those older than the statutory defined retirement age may continue to work, either out of enjoyment or necessity. However, depending on the nature of the job, older workers may need to transition into less-physical forms of work to avoid injury. Working past retirement age also has positive effects, because it gives a sense of purpose and allows people to maintain social networks and activity levels.[39] Older workers are often found to be discriminated against by employers.[40]

Working poor

Employment is no guarantee of escaping poverty, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that as many as 40% of workers are poor, not earning enough to keep their families above the $2 a day poverty line.[33] For instance, in India most of the chronically poor are wage earners in formal employment, because their jobs are insecure and low paid and offer no chance to accumulate wealth to avoid risks.[33] According to the UNRISD, increasing labor productivity appears to have a negative impact on job creation: in the 1960s, a 1% increase in output per worker was associated with a reduction in employment growth of 0.07%, by the first decade of this century the same productivity increase implies reduced employment growth by 0.54%.[33] Both increased employment opportunities and increased labor productivity (as long as it also translates into higher wages) are needed to tackle poverty. Increases in employment without increases in productivity leads to a rise in the number of "working poor", which is why some experts are now promoting the creation of "quality" and not "quantity" in labor market policies.[33] This approach does highlight how higher productivity has helped reduce poverty in East Asia, but the negative impact is beginning to show.[33] In Vietnam, for example, employment growth has slowed while productivity growth has continued.[33] Furthermore, productivity increases do not always lead to increased wages, as can be seen in the United States, where the gap between productivity and wages has been rising since the 1980s.[33]

Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute argue that there are differences across economic sectors in creating employment that reduces poverty.[33] 24 instances of growth were examined, in which 18 reduced poverty. This study showed that other sectors were just as important in reducing unemployment, such as manufacturing.[33] The services sector is most effective at translating productivity growth into employment growth. Agriculture provides a safety net for jobs and economic buffer when other sectors are struggling.[33]

| Growth, employment and poverty[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of episodes | Rising agricultural employment | Rising industrial employment | Rising services employment | |

| Growth episodes associated with falling poverty rates | ||||

| Growth episodes associated with no fall in poverty rates | ||||

Models of the employment relationship

Scholars conceptualize the employment relationship in various ways.[41] A key assumption is the extent to which the employment relationship necessarily includes conflicts of interests between employers and employees, and the form of such conflicts.[42] In economic theorizing, the labor market mediates all such conflicts such that employers and employees who enter into an employment relationship are assumed to find this arrangement in their own self-interest. In human resource management theorizing, employers and employees are assumed to have shared interests (or a unity of interests, hence the label “unitarism”). Any conflicts that exist are seen as a manifestation of poor human resource management policies or interpersonal clashes such as personality conflicts, both of which can and should be managed away. From the perspective of pluralist industrial relations, the employment relationship is characterized by a plurality of stakeholders with legitimate interests (hence the label “pluralism), and some conflicts of interests are seen as inherent in the employment relationship (e.g., wages v. profits). Lastly, the critical paradigm emphasizes antagonistic conflicts of interests between various groups (e.g., the competing capitalist and working classes in a Marxist framework) that are part of a deeper social conflict of unequal power relations. As a result, there are four common models of employment:[43]

- Mainstream economics: employment is seen as a mutually advantageous transaction in a free market between self-interested legal and economic equals

- Human resource management (unitarism): employment is a long-term partnership of employees and employers with common interests

- Pluralist industrial relations: employment is a bargained exchange between stakeholders with some common and some competing economic interests and unequal bargaining power due to imperfect labor markets[33]

- Critical industrial relations: employment is an unequal power relation between competing groups that is embedded in and inseparable from systemic inequalities throughout the socio-politico-economic system.

These models are important because they help reveal why individuals hold differing perspectives on human resource management policies, labor unions, and employment regulation.[44] For example, human resource management policies are seen as dictated by the market in the first view, as essential mechanisms for aligning the interests of employees and employers and thereby creating profitable companies in the second view, as insufficient for looking out for workers’ interests in the third view, and as manipulative managerial tools for shaping the ideology and structure of the workplace in the fourth view.[45]

Academic literature

Literature on the employment impact of economic growth and on how growth is associated with employment at a macro, sector and industry level was aggregated in 2013.[46]

Researchers found evidence to suggest growth in manufacturing and services have good impact on employment. They found GDP growth on employment in agriculture to be limited, but that value-added growth had a relatively larger impact.[33] The impact on job creation by industries/economic activities as well as the extent of the body of evidence and the key studies. For extractives, they again found extensive evidence suggesting growth in the sector has limited impact on employment. In textiles, however, although evidence was low, studies suggest growth there positively contributed to job creation. In agri-business and food processing, they found impact growth to be positive.[46]

They found that most available literature focuses on OECD and middle-income countries somewhat, where economic growth impact has been shown to be positive on employment. The researchers didn't find sufficient evidence to conclude any impact of growth on employment in LDCs despite some pointing to the positive impact, others point to limitations. They recommended that complementary policies are necessary to ensure economic growth's positive impact on LDC employment. With trade, industry and investment, they only found limited evidence of positive impact on employment from industrial and investment policies and for others, while large bodies of evidence does exist, the exact impact remains contested.[46]

Researchers have also explored the relationship between employment and illicit activities. Using evidence from Africa, a research team found that a program for Liberian ex-fighters reduced work hours on illicit activities. The employment program also reduced interest in mercenary work in nearby wars. The study concludes that while the use of capital inputs or cash payments for peaceful work created a reduction in illicit activities, the impact of training alone is rather low.[47]

Globalization and employment relations

The balance of economic efficiency and social equity is the ultimate debate in the field of employment relations.[48] By meeting the needs of the employer; generating profits to establish and maintain economic efficiency; whilst maintaining a balance with the employee and creating social equity that benefits the worker so that he/she can fund and enjoy healthy living; proves to be a continuous revolving issue in westernized societies.[48]

Globalization has affected these issues by creating certain economic factors that disallow or allow various employment issues. Economist Edward Lee (1996) studies the effects of globalization and summarizes the four major points of concern that affect employment relations:

- International competition, from the newly industrialized countries, will cause unemployment growth and increased wage disparity for unskilled workers in industrialized countries. Imports from low-wage countries exert pressure on the manufacturing sector in industrialized countries and foreign direct investment (FDI) is attracted away from the industrialized nations, towards low-waged countries.[48]

- Economic liberalization will result in unemployment and wage inequality in developing countries. This happens as job losses in uncompetitive industries outstrip job opportunities in new industries.

- Workers will be forced to accept worsening wages and conditions, as a global labor market results in a “race to the bottom”. Increased international competition creates a pressure to reduce the wages and conditions of workers.[48]

- Globalization reduces the autonomy of the nation state. Capital is increasingly mobile and the ability of the state to regulate economic activity is reduced.

What also results from Lee's (1996) findings is that in industrialized countries an average of almost 70 per cent of workers are employed in the service sector, most of which consists of non-tradable activities. As a result, workers are forced to become more skilled and develop sought after trades, or find other means of survival. Ultimately this is a result of changes and trends of employment, an evolving workforce, and globalization that is represented by a more skilled and increasing highly diverse labor force, that are growing in non standard forms of employment (Markey, R. et al. 2006).[48]

Alternatives

Subcultures

Various youth subcultures have been associated with not working, such as the hippie subculture in the 1960s and 1970s (which endorsed the idea of "dropping out" of society) and the punk subculture, in which some members live in anarchist squats (illegal housing).

Postsecondary education

One of the alternatives to work is engaging in postsecondary education at a college, university or professional school. One of the major costs of obtaining a postsecondary education is the opportunity cost of forgone wages due to not working. At times when jobs are hard to find, such as during recessions, unemployed individuals may decide to get postsecondary education, because there is less of an opportunity cost.

Workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in all its forms (including voting systems, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, systems of appeal) to the workplace.[49][50]

Self-employment

When an individual entirely owns the business for which they labor, this is known as self-employment. Self-employment often leads to incorporation. Incorporation offers certain protections of one's personal assets.[48] Individuals who are self-employed may own a small business. They may also be considered to be an entrepreneur.

Social assistance

In some countries, individuals who are not working can receive social assistance support (e.g., welfare or food stamps) to enable them to rent housing, buy food, repair or replace household goods, maintenance of children and observe social customs that require financial expenditure.

Volunteerism

Workers who are not paid wages, such as volunteers who perform tasks for charities, hospitals or not-for-profit organizations, are generally not considered employed. One exception to this is an internship, an employment situation in which the worker receives training or experience (and possibly college credit) as the chief form of compensation.[49]

Indentured servitude and slavery

Those who work under obligation for the purpose of fulfilling a debt, such as indentured servants, or as property of the person or entity they work for, such as slaves, do not receive pay for their services and are not considered employed. Some historians suggest that slavery is older than employment, but both arrangements have existed for all recorded history. Indentured servitude and slavery are not considered compatible with human rights or with democracy.[49]

See also

- Alternative employment arrangements

- Automation

- Basic income

- Domestic inquiry

- Employer branding

- Employment gap

- Employment rate

- Employment website

- Equal opportunity employment

- Equal pay for equal work

- Ethnic Penalty

- Faithless servant

- Green growth

- Job analysis

- Job description

- Jobless recovery

- Labor economics

- Labor power

- List of largest employers

- Lump of labor fallacy

- Onboarding

- Payroll

- Personnel selection

- Protestant work ethic

- Reserve army of labor (Marxism)

- Staffing models

- The End of Work

Notes and references

- Dakin, Stephen; Armstrong, J. Scott (1989). "Predicting job performance: A comparison of expert opinion and research findings" (PDF). International Journal of Forecasting. 5 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1016/0169-2070(89)90086-1. S2CID 14567834.

- Archer, Richard; Borthwick, Kerry; Travers, Michelle; Ruschena, Leo (2017). WHS: A Management Guide (4 ed.). Cengage Learning Australia. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-17-027079-3. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

The most significant definitions are 'person conducting a business or undertaking' (PCBU). 'worker' and 'workplace'. [...] 'PCBU' is a wider ranging term than 'employer', though this will be what most people understand by it.

- Robert A. Ristau (2010). Intro to Business. Cengage Learning. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-538-74066-1.

- Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court, 4, April 30, 2018, p. 903, retrieved 2020-03-30

- "Overview of Independent Contractor Guidelines". Findlaw. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- "Employer Liability for Employee Conduct". Findlaw. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- J. Mayhew Wainwright (1910). Report to the Legislature of the State of New York by the Commission appointed under Chapter 518 of the laws of 1909 to inquire into the question of employers' liability and other matters (Report). J. B. Lyon Company. pp. 11, 50, 144.

- Deakin, Simon; Wilkinson, Frank (2005). The Law of the Labour Market (PDF). Oxford University Press.

- Glynn, Timothy P.; Arnow-Richman, Rachel S.; Sullivan, Charles A. (2019). Employment Law: Private Ordering and Its Limitations. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. ISBN 9781543801064 – via Google Books.

- Annual Institute on Employment Law. 2. Practising Law Institute. 2004 – via Google Books.

- New York Jurisprudence 2d. 52. West Group. 2009 – via Google Books.

- Labor Cases. 158. Commerce Clearing House. 2009 – via Google Books.

- Ellie Kaufman (May 19, 2018). "Met Opera sues former conductor for $5.8 million over sexual misconduct allegations". CNN.

- Marx, Karl (1847). "Chapter 2". Wage Labour and Capital.

- Ellerman 1992.

- Ostergaard 1997, p. 133.

- Thompson 1966, p. 599.

- Thompson 1966, p. 912.

- Lazonick, William (1990). Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-674-15416-2.

- "wage slave". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "wage slave". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- "...vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen whom we pay for mere manual labour, not for artistic skill; for in their case the very wage they receive is a pledge of their slavery." – De Officiis

- "As long as politics is the shadow cast on society by big business, the attenuation of the shadow will not change the substance", in "The Need for a New Party" (1931), Later Works 6, p163

- Ferguson 1995.

- "House of Reps seals 'death' of WorkChoices". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2008-03-19. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- "Brown v. J. Kaz, Inc., No. 08-2713 (3d Cir. Sept. 11, 2009)". Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "Contract types and employer responsibilities". gov.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c)

- United States v. Latham, 754 F.2d 747, 750 (7th Cir. 1985).

- "Termination". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey (2018). Dying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance—and What We Can Do About It. HarperBusiness. p. 38. ISBN 978-0062800923.

- Lag om anställningsskydd (1982:80)

- Claire Melamed, Renate Hartwig and Ursula Grant 2011. Jobs, growth and poverty: what do we know, what don't we know, what should we know? Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine London: Overseas Development Institute

- "Bluenomics". Archived from the original on 2014-11-17.

- "Young Worker Safety and Health". www.cdc.gov. CDC NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- "Work-Related Motor Vehicle Crashes" (PDF). NIOSH Publication 2013-153. NIOSH. September 2013.

- "Work-Related Motor Vehicle Crashes: Preventing Injury to Young Drivers" (PDF). NIOSH Publication 2013-152. NIOSH. September 2013.

- Joseph Holden, Youth employment programmes – What can be learnt from international experience with youth employment programmes? Economic and private sector professional evidence and applied knowledge services https://partnerplatform.org/?fza26891

- Chosewood, L. Casey (May 3, 2011). "When It Comes to Work, How Old Is Too Old?". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH.

- Baert, Stijn (February 20, 2016). "Getting Grey Hairs in the Labour Market: An Alternative Experiment on Age Discrimination". Journal of Economic Psychology. 57: 86–101. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2016.10.002. hdl:10419/114164. S2CID 38265879.

- Kaufman, Bruce E. (2004) Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship, Industrial Relations Research Association.

- Fox, Alan (1974) Beyond Contract: Work, Power and Trust Relations, Farber and Farber.

- Budd, John W. and Bhave, Devasheesh (2008) "Values, Ideologies, and Frames of Reference in Industrial Relations," in Sage Handbook of Industrial Relations, Sage.

- Befort, Stephen F. and Budd, John W. (2009) Invisible Hands, Invisible Objectives: Bringing Workplace Law and Public Policy Into Focus, Stanford University Press.

- Budd, John W. and Bhave, Devasheesh (2010) "The Employment Relationship," in Sage Handbook of Handbook of Human Resource Management, Sage.

- Yurendra Basnett and Ritwika Sen, What do empirical studies say about economic growth and job creation in developing countries? Economic and private sector professional evidence and applied knowledge services https://partnerplatform.org/?7ljwndv4

- Blattman, Christopher; Annan, Jeannie (2016-02-01). "Can Employment Reduce Lawlessness and Rebellion? A Field Experiment with High-Risk Men in a Fragile State". American Political Science Review. 110 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1017/S0003055415000520. ISSN 0003-0554.

- Budd, John W. (2004) Employment with a Human Face: Balancing Efficiency, Equity, and Voice, Cornell University Press.

- Rayasam, Renuka (24 April 2008). "Why Workplace Democracy Can Be Good Business". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Wolff, Richard D. (2012). Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-60846-247-6.

Bibliography

- Acocella, Nicola (2007). Social pacts, employment and growth: a reappraisal of Ezio Tarantelli's thought. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7908-1915-1.

- Anderson, Elizabeth (2017). Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don't Talk about It). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17651-2.

- Dubin, Robert (1958). The World of Work: Industrial Society and Human Relations. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall. p. 213. OCLC 964691.

- Freeman, Richard B.; Goroff, Daniel L. (2009). Science and Engineering Careers in the United States: An Analysis of Markets and Employment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-26189-8.

- Lee, Eddy (January 1996). "Globalization and Employment: Is Anxiety Justified?". International Labour Review. 135 (5): 485–98. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16. Retrieved 2017-08-27 – via Questia.

- Markey, Raymond; Hodgkinson, Ann; Kowalczyk, Jo (2002). "Gender, part-time employment and employee participation in Australian workplaces". Employee Relations. 24 (2): 129–50. doi:10.1108/01425450210420884.

- Stone, Raymond J. (2005). Human Resource Management (5th ed.). Milton, Qld: John Wiley. pp. 412–14. ISBN 978-0-470-80403-2.

- Wood, Jack M. (2004). Organisational Behaviour: A Global Perspective (3rd ed.). Milton, Qld: Wiley. pp. 355–57. ISBN 978-0-470-80262-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Employment. |

The dictionary definition of employment at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of employment at Wiktionary- "Business Link". Businesslink.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012.

- "Labor and Employment". Government Information Library. University of Colorado at Boulder. Archived from the original on 2009-06-12. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- "Overview and topics of labour statistics". Statistics and databases. International Labour Organization.