Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

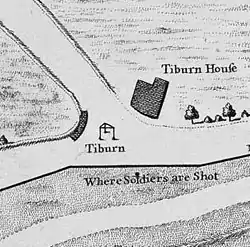

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman Roads to the west (modern Edgeware Road) and south (modern Oxford Street), the junction of these was the site of the famous Tyburn Gallows, now occupied by Marble Arch. For this reason, for many centuries, the name Tyburn was synonymous with capital punishment, it having been the principal place for execution of London criminals and convicted traitors, including many religious martyrs. It was also known as 'God's Tribunal', in the 18th century.[1]

Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne means 'boundary stream',[2] but Tyburn Brook should not be confused with the better known River Tyburn, which is the next tributary of the River Thames to the east of the Westbourne.

History

The manor of Tyburn, along with neighbouring Lisson was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, and were together served by the parish of Marylebone; itself named after the stream, St Marylebone being a contraction of St Mary's church by the bourne. In the 1230s and 1240s the manor was held by Gilbert de Sandford, the son of John de Sandford, who had been the chamberlain to Eleanor of Aquitaine. In 1236 the city of London contracted with Sir Gilbert to draw water from Tyburn Springs, which he held, to serve as the source of the first piped water supply for the city. The water was supplied in lead pipes that ran from where Bond Street Station stands today, one-half mile (0.80 kilometres) east of Hyde Park, down to the hamlet of Charing (Charing Cross), along Fleet Street and over the Fleet Bridge, climbing Ludgate Hill (by gravitational pressure) to a public conduit at Cheapside. Water was supplied free to all comers.[3]

The junction of the two Roman Roads had significance from ancient times and was marked by a monument known as Oswulf's Stone, which gave its name to the Ossulstone Hundred of Middlesex. The stone was covered over in 1851 when Marble Arch was moved to the area, but it was shortly afterwards unearthed and propped up against the Arch. It has not been seen since 1869.

Tyburn gallows

Although executions took place elsewhere (notably on Tower Hill, generally related to treason), the Roman Road junction at Tyburn became associated with the place of criminal execution mostly after they were moved here from Smithfield in the 1400s.[4] Prisoners were taken in public procession from Newgate Prison in the City, via St Giles in the Fields and Oxford Street (then known as Tyburn Road). From the late 18th century, when public executions were no longer carried out at Tyburn, they occurred at Newgate Prison itself and at Horsemonger Lane Gaol in Southwark.

The first recorded execution took place at a site next to the stream in 1196. William Fitz Osbert, populist leader who played a major role in an 1196 popular revolt in London, was cornered in the church of St Mary-le-Bow. He was dragged naked behind a horse to Tyburn, where he was hanged.[5]

In 1537, Henry VIII used Tyburn to execute the ringleaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace, including Sir Nicholas Tempest, one of the northern leaders of the Pilgrimage and the King's own Bowbearer of the Forest of Bowland.[6]

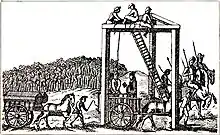

In 1571, the Tyburn Tree was erected near the junction of today's Edgware Road, Bayswater Road and Oxford Street, 200 metres (660 ft) west of Marble Arch. The "Tree" or "Triple Tree" was a form of gallows, consisting of a horizontal wooden triangle supported by three legs (an arrangement known as a "three-legged mare" or "three-legged stool"). Several criminals could thus be hanged at once, and so the gallows were used for mass executions, such as on 23 June 1649 when 24 prisoners—23 men and one woman—were hanged simultaneously, having been conveyed there in eight carts.[7]

After executions, the bodies would be buried nearby or in later times removed for dissection by anatomists.[8] The crowd would sometimes fight over a body with surgeons, for fear that dismemberment could prevent the resurrection of the body on Judgement Day (see Jack Sheppard, Dick Turpin or William Spiggot).[9]

The first victim of the "Tyburn Tree" was John Story, a Roman Catholic who was convicted and tried for treason.[10] A plaque to the Catholic martyrs executed at Tyburn in the period 1535–1681 is located at 8 Hyde Park Place, the site of Tyburn convent.[11] Among the more notable individuals suspended from the "Tree" in the following centuries were John Bradshaw, Henry Ireton and Oliver Cromwell, who were already dead but were disinterred and hanged at Tyburn in January 1661 on the orders of the Cavalier Parliament in an act of posthumous revenge for their part in the beheading of King Charles I.[12]

The gallows seem to have been replaced several times, probably because of wear, but in general, the entire structure stood all the time in Tyburn. After some acts of vandalism, in October 1759 it was decided to replace the permanent structure with new moving gallows until the last execution in Tyburn, probably carried out in November 1783.[10]

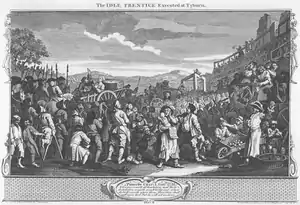

The executions were public spectacles which attracted crowds of thousands. Spectator stands provided deluxe views for a fee. On one occasion, the stands collapsed, reportedly killing and injuring hundreds of people. This did not prove a deterrent, however, and the executions continued to be treated as public holidays, with London apprentices being given the day off for them. One such event was depicted by William Hogarth in his satirical print The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn (1747).

Tyburn was commonly invoked in euphemisms for capital punishment—for instance, to "take a ride to Tyburn" (or simply "go west") was to go to one's hanging, "Lord of the Manor of Tyburn" was the public hangman, "dancing the Tyburn jig" was the act of being hanged. Convicts would be transported to the site in an open ox-cart from Newgate Prison. They were expected to put on a good show, wearing their finest clothes and going to their deaths with insouciance. The crowd would cheer a "good dying", but would jeer any displays of weakness on the part of the condemned.

On 19 April 1779, clergyman James Hackman was hanged there following his 7 April murder of courtesan and socialite Martha Ray, the mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. The Tyburn gallows were last used on 3 November 1783, when John Austin, a highwayman, was hanged; for the next eighty-five years hangings were staged outside Newgate prison. Then, in 1868, due to public disorder during these public executions, it was decided to execute the convicts inside the prison.[13]

The site of the gallows is now marked by three young oak trees that were planted in 2014 on an island in the middle of Edgware Road at its junction with Bayswater Road. Between the trees is a roundel with the inscription "The site of Tyburn Tree".[14] It is also commemorated by the Tyburn Convent,[15] a Catholic convent dedicated to the memory of martyrs executed there and in other locations for the Catholic faith.

Although most historical records and modern science agree that the Tyburn gallows were situated where Oxford Street meets Edgware Road and Bayswater Road, in the January 1850 issue of Notes and Queries, the book collector and musicologist Edward Francis Rimbault published a list of faults he had found in Peter Cunningham's 1849 Handbook of London, in which he claimed that the correct site of the gallows is where 49 Connaught Square later was built, stating that "in the lease granted by the Bishop of London, this is particularly mentioned".[16]

Process of executions

Tyburn was primarily known for its gallows, which functioned as the main execution site for London-area prisoners from the 16th through to the 18th centuries. For those people found guilty of capital crimes who could not get a pardon, which accounted for approximately 40%, a probable destiny was to be hanged at Tyburn. Other contemporary methods of punishment that may have been used as alternatives to Tyburn included execution, followed by being hung in chains, where the crime was committed; or burning at the stake; and being drawn and quartered, of which the latter two were common in cases of treason.

The last days of the condemned were marked by religious events. On the Sunday before every execution, a sermon was preached in Newgate's chapel, which those unaffiliated with the execution could pay to attend. Furthermore, the night before the execution, around midnight, the sexton of St Sepulchre's church, adjacent to Newgate, recited verses outside the wall of the condemned. The following morning, the convicts heard prayers and, those who wished to do so, received the sacrament.

On the day of execution, the condemned were transported to the Tyburn gallows from Newgate in a horse-drawn open cart. The distance between Newgate and Tyburn was approximately three miles (4.8 kilometres), but due to streets often being crowded with onlookers, the journey could last up to three hours. A usual stop of the cart was at the Bowl Inn in St Giles, where the condemned were allowed to drink strong liquors or wine.[17]

Having arrived at Tyburn, the condemned found themselves in front of a crowded and noisy square; the wealthy paid to sit on the stands erected for the occasion, in order to have an unobstructed view. Before the execution, the condemned were allowed to say a few words—the authorities expected that most of the condemned, before their death, before commending their own souls to God, would admit their guilt. It is reported that the majority of the condemned did so. A noose was then placed around their neck and the cart pulled away, leaving them hanging. Death was not immediate; the fight against strangulation could last for three-quarters of an hour.

Instances of pickpocketing have been reported in the crowds of executions, a mockery of the deterrent effect of capital punishment, which at the time was considered proper punishment for theft.[13][18][19]

Social aspects

Sites of public executions were significant gathering places and executions were public spectacles. Scholars have described the executions at Tyburn as "carnivalesque occasion[s] in which the normative message intended by the authorities is reappropriated and inverted by an irreverent crowd" that found them a source of "entertainment as well as conflict." This analysis is supported by the presence of shouting street traders and food vendors and the erection of seating for wealthier onlookers.[20][21] Additionally, a popular belief held that the hand of an executed criminal could cure cancers, and it was not uncommon to see mothers brushing their child's cheek with the hand of the condemned.[22] The gallows at Tyburn were sources of cadavers for surgeons and anatomists.[22]

Executioners

- "The hangman of London " Cratwell c. 1534[23] - 1 September 1538[24][25][26]

- Thomas Derrick c. 1608

- Gregory Brandon 1625 (or earlier) – ?, after whom the phrase the "Gregorian tree" was coined.[27]

- Robert Brandon - 1649 "Young Gregory" alongside his father at least part of the period.[27]

- Edward Dun

- Jack Ketch 1663 – early 1686, reinstated briefly in late 1686

- Paskah Rose 1686 – 28 May 1686

- Richard Pearse (?) 1686–?

- Unknown or unknowns

- John Price 1714–16

- William Marvell 1716 – November 1717

- John Price 1717–18

- William Marvell (?) 1718

- Bailiff Banks ?–1719

- Richard Arnet 1719 – c. 1726

- John Hooper ? – March 1735

- John Thrift March 1735 – May 1752

- Thomas Turlis 1754–1771

- Edward Dennis 1771 – 21 November 1786

Notable executions

| Name | Date | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| William Fitz Osbert | 1196 | Citizen of London executed for his role in a popular uprising of the poor in the spring of 1196.[28] |

| Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March | 29 November 1330 | Accused of assuming royal power; hanged without trial.[29] |

| Sir Thomas Browne, MP, Sheriff of Kent | 20 July 1460 | Convicted of treason and immediately hanged. Had been knighted by Henry IV and served as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1440 and 1450 and as Justice of the peace in Surrey from 1454 until his death. |

| Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton | 8 July 1486 | Accused of siding with Richard III; hanged without trial on orders of Henry VII. |

| Michael An Gof and Thomas Flamank | 27 June 1497[30] | Leaders of the 1st Cornish Rebellion of 1497. |

| Perkin Warbeck | 23 November 1499 | Treason; pretender to the throne of Henry VII of England by passing himself off as Richard IV, the younger of the two Princes in the Tower. Leader of the 2nd Cornish Rebellion of 1497.[31] |

| Elizabeth Barton "The Holy Maid of Kent" | 20 April 1534 | Treason; a nun who unwisely prophesied that King Henry VIII would die within six months if he married Anne Boleyn.[32] |

| John Houghton | 4 May 1535 | Prior of the Charterhouse who refused to swear the oath condoning King Henry VIII's divorce of Catherine of Aragon.[33] |

| Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare | 3 February 1537 | Rebel who renounced his allegiance to Henry VIII. On 3 February 1537, the Earl, after being imprisoned for sixteen months, along with five of his uncles, were all executed as traitors at Tyburn, by being hanged, drawn and quartered. The Irish Government, not satisfied with the arrest of the Earl, had written to Cromwell and it was determined that the five uncles (James, Oliver, Richard, John and Walter) should be arrested also.[34]

The sole male representative to the Kildare Geraldines was then smuggled to safety by his tutor at the age of twelve. Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare (1525–1585), also known as the "Wizard Earl". |

| Sir Francis Bigod | 2 June 1537 | Leader of Bigod's Rebellion. Between June and August 1537, the rebellion's ringleaders and many participants were executed at Tyburn, Tower Hill and many other locations. They included Sir John Bigod, Sir Thomas Percy, Sir Henry Percy, Sir John Bulmer,[35] Sir Stephan Hamilton, Sir Nicholas Tempast, Sir William Lumley, Sir Edward Neville, Sir Robert Constable, the abbots of Barlings, Sawley, Fountains and Jervaulx Abbeys, and the prior of Bridlington. In all, 216 were put to death in various places; lords and knights, half a dozen abbots, 38 monks, and 16 parish priests.[36] |

| Thomas Fiennes, 9th Baron Dacre | 29 June 1541 | Lord Dacre was convicted of murder after being involved in the death of a gamekeeper whilst taking part in a poaching expedition on the lands of Sir Nicholas Pelham of Laughton.[37] |

| Francis Dereham and Sir Thomas Culpeper | 10 December 1541 | Courtiers of King Henry VIII who were sexually involved with his fifth wife, Queen Catherine Howard. Culpeper and Dereham were both sentenced to be 'hanged, drawn and quartered' but Culpeper's sentence was commuted to beheading at Tyburn on account of his previously good relationship with Henry. (Beheading, reserved for nobility, was normally carried out at Tower Hill.) Dereham suffered the full sentence. |

| William Leech of Fulletby | 8 May 1543 | A ringleader of the rebellion called the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536, Leech escaped to Scotland. He murdered the Somerset Herald, Thomas Trahern, at Dunbar on 25 November 1542, causing an international incident, and was delivered for hanging in London.[38] |

| Humphrey Arundell | 27 January 1550 | Leader of the Western Rebellion in 1549 – sometimes known as the Prayer Book Rebellion[39] |

| Saint Edmund Campion[40] | 1 December 1581 | Roman Catholic priests. |

| John Adams[41] | 8 October 1586 | |

| Robert Dibdale[42] | ||

| John Lowe[43] | ||

| Brian O'Rourke | 3 November 1591 | Irish lord, harboured and aided the escape of Spanish Armada shipwreck survivors in the winter of 1588. Following a short rebellion he fled to Scotland in 1591, but became the first man extradited within Britain on allegations of crimes committed in Ireland and was sentenced to death for treason. |

| Robert Southwell[44] | 21 February 1595 | Roman Catholic priest. |

| John Felton | 29 November 1628 | Lieutenant in the English army who murdered George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, a courtier, statesman, and favorite of King James I. |

| Philip Powel | 30 June 1646 | Roman Catholic priests. |

| Peter Wright | 19 May 1651 | |

| John Southworth[45] | 28 June 1654 | |

| Oliver Cromwell | 30 January 1661 | Posthumous execution following exhumation of his body from Westminster Abbey. |

| Robert Hubert | 28 September 1666 | Falsely confessed to starting the Great Fire of London.[46] |

| Claude Duval | 21 January 1670 | Highwayman.[47] |

| Saint Oliver Plunkett | 1 July 1681 | Lord Primate of All Ireland, Lord Archbishop of Armagh and martyr.[48] |

| Jane Voss | 19 December 1684 | Robbing on the highway, high treason, murder, and felony. |

| William Chaloner | 23 March 1699 | Notorious coiner and counterfeiter, convicted of high treason partly on evidence gathered by Isaac Newton. |

| Jack Hall | 1707 | A chimney-sweep, hanged for committing a burglary. There is a folk-song about him, which bears his name (and another song with the variant name of Sam Hall). |

| Henry Oxburgh | 14 May 1716 | One of the Jacobite leaders of the 1715 Rebellion. |

| Jack Sheppard "Gentleman Jack" | 16 November 1724 | Notorious thief[49] and multiple escapee. |

| Jonathan Wild | 24 May 1725 | Organized crime lord.[49] |

| Arthur Gray | 11 May 1748 | One of the leaders of the notorious Hawkhurst Gang, a criminal organisation involved in smuggling throughout southeast England from 1735 until 1749.[50] |

| James MacLaine "The Gentleman Highwayman" | 3 October 1750 | Highwayman.[51] |

| Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers | 1 May 1760 | The last peer to be hanged for murder.[52] |

| Elizabeth Brownrigg | 13 September 1767 | Murdered Mary Clifford, a domestic servant.[53] |

| John Rann "Sixteen String Jack" | 30 November 1774 | Highwayman. |

| Rev. James Hackman | 19 April 1779 | Hanged for the murder of Martha Ray, mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.[54] |

| John Austin | 3 November 1783 | A highwayman, the last person to be executed at Tyburn.[55] |

See also

- Thomas Derrick an executioner at Tyburn.

- Carthusian Martyrs of London

- Last dying speeches

- Ordinary of Newgate's Account

Notes

- Andrea McKenzie, Tyburn's martyres, preface pp. XV–XX.

- Gover J.E.B., Allen Mawer and F.M. Stenton The Place-Names of Middlesex. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society, The, 1942: 6.

- Stephen Inwood, A History of London (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1998), p. 125. Also see D. P. Johnson (ed.), English Episcopal Acta, Vol. 26: London, 1189–1228 (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press for the British Academy, 2003), Doc. 88, pp. 85–86.

- Smith, Oliver (25 January 2018). "'Strike, man, strike!' – On the trail of London's most notorious public execution sites". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- London (England) Grey friars (Monastery); Nichols, John Gough (1852). Chronicle of the Grey friars of London. University of California Libraries. [London] Printed for the Camden society.

- RW Hoyle, The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s (Oxford University Press: Oxford 2001)

- Norton, Rictor. "The Underworld and Popular Culture (The Georgian Underworld, Ch. 17)". rictornorton.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Mitchell, PD; Boston, C; Chamberlain, AT; Chaplin, S; Chauhan, V; Evans, J; Fowler, L; Powers, N; Walker, D; Webb, H; Witkin, A. "The study of anatomy in England from 1700 to the early 20th century". J Anat. 219: 91–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01381.x. PMC 3162231. PMID 21496014.

- McKenzie, Andrea (2007). Tyburn's Martyrs, Executions in England 1675-1775. London, England: Hambledon Continuum, Continuum Books. pp. 20, 21. ISBN 978-1847251718.

- McKenzie, Andrea (2007). Tyburn's Martyrs, Executions in England 1675-1775. London, England: Hambledon Continuum, Continuum Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-1847251718.

- City of Westminster green plaques "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- House of Commons (1802). "Journal of the House of Commons: volume 8: 1660–1667". pp. 26–7. Attainder predated to 1 January 1649 (It is 1648 in the document because of old style year)

- "Crime and Justice - Punishment Sentences at the Old Bailey - Central Criminal Court". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "'Tyburn Tree' Memorial Renewed". Diocese of Westminster. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- Tyburn Convent website. Retrieved 10/8/07

- Notes and Queries, Number 12, 19 January 1850 by Various accessed 30 May 2007

- Tales from the Hanging Court, Tim Hitchcock & Robert Shoemaker, Bloomsbury, p. 306

- Tales from the Hanging Court, Tim Hitchcock & Robert Shoemaker, Bloomsbury, pp. 301, 307

- "Results - Central Criminal Court". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Tales from the Hanging Court, Tim Hitchcock & Robert Shoemaker, Bloomsbury, pp. 305, 306;

- McKenzie, Andrea (2007). Tyburn's Martyrs, Executions in England 1675-1775. London, England: Hambledon Continuum, Continuum Books. pp. 21, 24. ISBN 978-1847251718.

- Tales from the Hanging Court, Tim Hitchcock & Robert Shoemaker, Bloomsbury, pp. 309, 316;

- The Old Bailey and its trials. 1950.

- A Chronicle of England During the Reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559 Wriothsley

- Tyburn Tree: Its History and Annals

-

And the Sonday after Bartelemew daye, was one Cratwell, hangman of London, and two persones more hanged at the wrestlying place on the backesyde of Clarkenwell besyde London

Hall. Hen. VIII an. 30, cited in A New Dictionary of the English Language, Charles Richardson (1836) William Pickering, London. Vol 1 P. 962, col 1 - Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable

- Historia rerum anglicarum, Book 5 Ch.20

- Ian Mortimer The Greatest Traitor (2003)

- "Michael An Gof, the Cornish Blacksmith". www.cornwall-calling.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Ann Wroe Perkin: A Story of Deception., Vintage: 2004 (ISBN 0-09-944996-X)

- Alan Neame: The Holy Maid of Kent: The Life of Elizabeth Barton: 1506–1534 (London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1971) ISBN 0-340-02574-3

- "Blessed John Houghton". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "The Earls of Kildare and their Ancestors." by the Marquis of Kildare, 3rd edition 1858

- Emerson, Kathy Lynn A Who's Who of Tudor Women (2011) gives Bulmer's death date as 25 August 1537

- Thomas Percy, Sir Knight at geni.com (citing as source Adams, Arthur, and Howard Horace Angerville. Living Descendants of Blood Royal London: World Nobility and Peerage, 1959. Vol. 4-page 417.

- Luke MacMahon, Fiennes, Thomas, ninth Baron Dacre, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography accessed 30 May 2007

- Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 8, 170.

- "Humphrey Arundell of Helland". Tudor Place. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- Evelyn Waugh's biography, Edmund Campion (1935)

- Godfrey Anstruther, Seminary Priests, St Edmund's College, Ware, vol. 1, 1968, pp. 1-2

- ibid pp 101

- ibid pp 214-5

- Bishop Challoner, Memoirs of Missionary Priests and other Catholics of both sexes that have Suffered Death in England on Religious Accounts from 1577 to 1684 (Manchester, 1803) vol.I, p. 175ff

- "St. John Southworth". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "The London Gazette", 10 September 1666

- Claude Du Vall: The Gallant Highwayman Stand and Deliver accessed 30 May 2007

- Blessed Oliver Plunkett: Historical Studies, Gill, Dublin (1937)

- Moore, Lucy. The Thieves' Opera. Viking (1997) ISBN 0-670-87215-6

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online 1674–1913. Execution of Arthur Gray. Ordinary's Account, 11 May 1748. Reference Number: OA17480511 Version 6.0 17 Retrieved 15 December 2018

- "James Maclane". The Newgate Calendar. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "Laurence Shirley, Earl Ferrers". The Newgate Calendar. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "Ordinary's Account, 14th September 1767". The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "James Hackman". The Newgate Calendar. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "Account of the Trial and Execution of John Austin". London Ancestor. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

References

- Heald, Henrietta (1992). Chronicle of Britain: Incorporating a Chronicle of Ireland. J L International Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-872031-35-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tyburn Tree. |

- Connected Histories

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.