Typhoon June (1984)

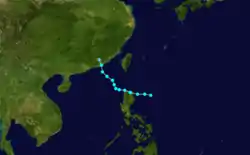

Typhoon June, also known in the Philippines as Typhoon Maring, was the first of two tropical cyclones to affect the Philippines in a one-week time span in August 1984. June originated from an area of convection that was first witnessed on August 15 in the Philippine Sea. Despite initial wind shear, the area intensified into a tropical storm three days later as it tracked westward. After tracking over Luzon, June entered the South China Sea on August 30. Despite remaining poorly organized, June re-intensified over land, and it was estimated to have briefly attained typhoon intensity before striking China, just to the east of Hong Kong, at maximum intensity, although its remnants were last noticed on September 3.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

June on August 29 at 07:27 UTC | |

| Formed | August 26, 1984 |

| Dissipated | September 1, 1984 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 120 km/h (75 mph) 1-minute sustained: 110 km/h (70 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 985 hPa (mbar); 29.09 inHg |

| Fatalities | 121 total, 17 missing |

| Damage | $24.2 million (1984 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| Part of the 1984 Pacific typhoon season | |

Affecting the country four days before Typhoon Ike would devastate the Philippines, June brought widespread damage to the nation. Throughout the Philippines, 470,962 people sought shelter. A total of 671 homes were destroyed, with 6,341 others damaged. A total of 121 people were killed, while 17 other individuals were reportedly missing, and 26 other people were wounded. Damage totaled $24.2 million (1984 USD, including $15.24 million in agriculture and $8.82 million in infrastructure). Following June and Ike, several major countries provided cash and other goods. In all, $7.5 million worth of aid was donated to the nation in relief. In addition to effects on the Philippines, 1,500 homes were damaged and 66,000 ha (160,000 acres) of farmland were flooded in the Guangdong province.

Meteorological history

Typhoon June, the final of seven tropical cyclones to develop in the Western Pacific basin in August 1984, formed from the monsoon trough. A large area of convection was first detected on satellite imagery, and at midday, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center determined that a closed area of low pressure developed between the 135th meridian east and the 140th meridian east. The associated thunderstorm activity initially failed to consolidate due to strong wind shear caused by a displaced anticyclone.[1] The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) started to track the system 06:00 UTC on August 26.[2][nb 1] The next day, the wind shear began to relent, as an upper-level anticyclone became located over the system as the system tracked westward, although the circulation remained tough to identify by weather satellites. At 06:51 UTC on August 27, a Hurricane Hunter aircraft reported winds of 55 km/h (35 mph). Based on the above data and an increase in the system's organization, the JTWC issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert. On August 28, the storm's center of circulation became better defined,[1] and at 06:00 UTC, both the JTWC and JMA upgraded it to a tropical storm.[4][nb 2] Around this time, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also began to monitor the storm and assigned it with the local name Maring.[6]

Continuing westward due to a subtropical ridge to its north,[1] June slowly intensified.[7] On the afternoon of August 28, June made landfall along the coast of Luzon[1] as a strong tropical storm, with the JTWC and JMA estimating winds of 105 km/h (65 mph) and 80 km/h (50 mph) respectively.[4] Over land, the low- and mid-level circulations began to decouple, with the mid-level center and most of the deep convection continuing west and the low-level center veering west-northwest and early on August 29, the surface center re-merged into open water,[1] having weakened slightly according to both the JTWC and the JMA.[4] June began to turn northwest in response to a trough over the East China Sea.[1] At 18:00 UTC on August 29, the JMA classified June as a severe tropical storm.[2] Six hours later, the JTWC reported that June attained its peak intensity of 115 km/h (70 mph).[7] Despite lacking in organization,[7] a surface pressure of 986 mbar (29.1 inHg) was measured in Basco as the cyclone passed near the area.[8] The JMA declared June a typhoon at midday on August 30. At this time, it also estimated a peak intensity of 120 km/h (75 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 985 mbar (29.1 inHg).[2] Five hours later, June made landfall 240 km (150 mi) east of Hong Kong[1] while at peak intensity.[4] The JMA continued to follow the system inland throughout September 3.[2]

Impact

Typhoon June hit the Philippines four days before Typhoon Ike would devastate the archipelago.[9] The first storm to hit the Philippines in 1984, June brought rough seas from Luzon to Davao. Philippine Airlines suspended flights to eight cities and railway services to the northern portions of the island chain were also suspended.[10] Power was knocked out for four days across much of the country due to both systems.[9] Six people were killed in landslides that isolated the mountain resort city of Baguio, where five others were missing and seven were injured. According to the Philippine News Agency, a 22-year-old man picking seashells drowned after he was swept out to sea near Bacolod, on Negros Island. In San Fernando, located in the northern province of La Union, 200 houses were flattened and 120 people were injured. In Manila, heavy winds and rough seas left streets flooded, resulting in traffic jams.[10] The storm caused serious damage to the nation's rice fields, the country's main export.[9]

From the two storms combined, more than 1 million were displaced from their homes.[9] Throughout the Philippines, 470,962 people or 92,271 families sought shelter due to the typhoon,[11] of which 5,023 families or 30,138 people sought shelter in schools, churches and town halls in a total of 10 provinces.[10] A total of 671 homes were destroyed while 6,341 others were damaged. One hundred-twenty-one people were killed while 17 other individuals were reportedly missing and 26 other people were wounded.[11] The storm inflicted $24.2 million in damage, with $15.2 million in agriculture and $8.82 million in infrastructure.[12][nb 3]

Prior to its second landfall, in Hong Kong, a No 1. hurricane signal was issued after June entered the South China Sea. The storm brought heavy rains and strong winds to the region. A minimum pressure of 990 mbar (29 inHg) was recorded at the Hong Kong Royal Observatory early on August 30. Tate's Cairn recorded a peak wind speed of 50 km/h (31 mph) and a peak wind gust of 78 km/h (48 mph). Cheung Chau observed 187.3 mm (7.37 in) of rain over a five-day period. Although damage in Hong Kong was minimal, heavy rains in eastern Guangdong inundated 66,000 ha (163,090 acres) of farmland, and damage to 1,500 dwellings.[8]

Aftermath

Due to effects from both Ike and June, President Ferdinand Marcos set aside $4 million for relief work but initially refused any international aid.[13] He also traveled to Ilocos Norte to inspect damage.[14] The Philippines Air Force delivered 907,185 kg (2,000,000 lb) of food, medicine, and clothes.[15] According to officials, 92 health teams backed by 17 army medical units were fielded; these teams distributed $1.66 million worth of medicine.[16] The Philippine Red Cross disturbed food to 239,331 people, or 44,247 families.[17] On September 8, the nation abandoned its policy of refusing foreign aid, citing a lack of resources in the country due to its poor economy, as well as, the mass destruction across the country from both systems.[18] The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs gave an emergency grant of $50,000. UNICEF provided $116,000 worth of vitamins and medicine and an additional $116,950 in cash, as well as 28 short tons (25 t) of milk powder. Thy later provided vegetable seeds, died fish, and garden fertilizer. The World Health Organization provided $7,000 worth of aid. Furthermore, the United Nations Development Programme awarded the country $30,000 in cash. The European Economic Community provided 270 t (300 short tons) of milk and $367,650 worth of cash.[17] In the middle of September, the United States approved $1 million in aid to the archipelago. Japan also sent a $500,000 check.[19] Australia awarded almost $500,000 worth of cash and food. New Zealand donated 22,680 kg (50,000 lb) of skin milk. The Norwegian Red Cross provided $58,500 in aid while Belgium also provided three medical kits. The Swiss Red Cross awarded a little under $21,000 in cash. German provided slightly more than $50,000 in cash. France provided roughly $11,000 in donations to the nation's red cross. The Red Cross Society of China donated $20,000 in cash. Indonesia provided $25,000 worth of medicine. The United Kingdom granted $74,441 in aid. Overall, Relief Web reported that over $7.5 million was donated to the Philippines due to the storm.[17]

See also

- Typhoon Mike – Passed north of Mindanao and impacted the central Philippines, resulting in catastrophic damage

- Typhoon Nelson (1982) – Resulted in significant flooding across the Philippines after slowly traversing the archipelago

- Typhoon Lynn (1987)

- Tropical Storm Kelly

- Typhoon Agnes (1984) – Caused extensive damage and fatalities in the central Philippines before striking Vietnam

Notes

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10‑minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1‑minute winds.[5]

- All Philippine currencies are converted to United States Dollars using Philippines Measuring worth with an exchange rate of the year 1984.

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1987). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1984 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (Report). Archived from the original (.TXT) on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 June (1984238N18137). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Padua, Michael V. (November 6, 2008). PAGASA Tropical Cyclone Names 1963–1988 (TXT) (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Tropical Storm 14W Best Track (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. December 17, 2002. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Hong Kong Observatory (1985). "Part III – Tropical Cyclone Summaries". Meteorological Results: 1984 (PDF). Meteorological Results (Report). Hong Kong Observatory. pp. 26–29. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- "Typhoon death toll rises to 438, may go higher". United Press International. September 4, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Tropical storm kills 7, injures 127". United Press International. August 29, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 9, 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- "On This Day: September 3". British Broadcasting Company. September 3, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- "International News". United Press International. September 6, 1984.

- "Marcos Ventures Into Rebel Area That Was Ravaged by Typhoon". Associated Press. September 9, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Reed, Jack (September 6, 1984). "Typhoon death toll tops 1,360 in Philippines". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Philippines Typhoons Sep 1984 UNDRO Situation Reports 1 – 7 (Report). Relief Web. September 13, 1984. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- Reed, Jack (September 8, 1984). "International News". United Press International.

- "Foreign News Beliefs". United Press International. September 14, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)