USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641)

USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641), a Benjamin Franklin class fleet ballistic missile submarine, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), a hero of the independence movements of the former Spanish colonies in South America.

USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641) on 1 February 1991 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), a hero of South American independence movements |

| Awarded: | 1 November 1962 |

| Builder: | Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News, Virginia |

| Laid down: | 17 April 1963 |

| Launched: | 22 August 1964 |

| Sponsored by: | Mrs. Thomas C. Mann |

| Commissioned: | 29 October 1965 |

| Decommissioned: | 8 February 1995 |

| Stricken: | 8 February 1995 |

| Honors and awards: |

|

| Fate: | Scrapping via Ship and Submarine Recycling Program begun 1 October 1994; completed 1 December 1995 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Benjamin Franklin class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine |

| Displacement: | 6,494 tons |

| Length: | 425 feet (130 m) |

| Beam: | 33 feet (10 m) |

| Draft: | 32 feet (9.8 m) |

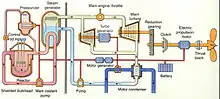

| Propulsion: | S5W reactor |

| Speed: |

|

| Test depth: | 1,300 feet (400 m) |

| Complement: | Two crews (Blue Crew and Gold Crew) of 14 officers and 126 enlisted men each |

| Armament: |

|

Construction and commissioning

Simon Bolivar's keel was laid down on 17 April 1963 by the Newport News Shipbuilding of Newport News, Virginia. She was launched on 22 August 1964, sponsored by Mrs. Thomas C. Mann, and commissioned on 29 October 1965 with Commander Charles H. Griffiths commanding the Blue Crew and Commander Charles A. Orem commanding the Gold Crew.

Service history

During late December 1965 and most of January 1966, Simon Bolivar underwent demonstration and shakedown operations. The Gold Crew successfully fired a Polaris A-3 ballistic missile off the coast of Cape Kennedy, Florida, on 17 January 1966, and the Blue Crew completed a successful Polaris missile firing on 31 January.

The Gold Crew continued shakedown operations in the Caribbean Sea in February. The following month, Simon Bolivar's home port was changed to Charleston, South Carolina, where she was assigned to Submarine Squadron 18, and minor deficiencies were corrected during a shipyard availability period.

In April 1966 Simon Bolivar got underway and went to alert status for the first of more than 70 strategic deterrent patrols spanning four decades and three major submarine launched ballistic missile weapons systems (Polaris, Poseidon, Trident).

During Simon Bolivar's commissioned period she operated in the Atlantic and Mediterranean from three sites: Holy Loch, Scotland; Rota, Spain; and the continental United States, mainly Charleston, SC and Kings Bay, GA. Refit sites consisted of a submarine tender, floating dry dock and complexes of piers and warehouses. At the Scotland site, the entire refit site was anchored out in Holy Loch.

Simon Bolivar's routine of deterrent patrols out of Charleston by her two crews continued until 7 February 1971, when she returned to Newport News for overhaul and conversion of her ballistic missile system to support Poseidon missiles.

Simon Bolivar departed Newport News on 12 May 1972 for post-overhaul shakedown operations and refresher training for her two crews, which lasted until 16 September 1972. By the end of 1972, she had resumed deterrent patrols while operating from the SSBN refit site in Rota, Spain serviced by submarine tender USS Simon Lake (AS-33) as part of Submarine Squadron 16.

During the summer of 1974, Simon Bolivar completed what was to be her final refit at the Rota SSBN site. Departing the site then diving, the ship headed southeasterly for passage through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea. She then went to alert status for her 24th deterrent patrol. Following completion of the patrol, the ship traveled westward across the Mediterranean through the Straits of Gibraltar and into the Atlantic. Seventy four days after departing Rota and submerging, Simon Bolivar surfaced off the US east coast in October 1974. Simon Bolivar had now been assigned to the Charleston refit site and was again part of Submarine Squadron 18. Submarine tender USS Hunley (AS-31) provided refit and re-supply services. Patrol areas were normally in the North Atlantic.

In 1974 Simon Bolivar was awarded both a Battle Effectiveness Award (Battle "E") and the Providence Plantation Award for most outstanding fleet ballistic missile submarine in the United States Atlantic Fleet. She also was awarded consecutive Battle "E"'s in 1975 and 1976.

During a 1976 strategic patrol, a crew member experienced a life-threatening medical emergency. The ship aborted its alert patrol status, and charted an easterly course for a high speed transit to a medevac point off the UK coast. Upon reaching shallow water of 100 fathoms, the ship surfaced into a raging winter storm with waves breaking repeatedly over the ship, its sail and the harnassed watchstanders in the cockpit of the sail. Inside the ship the crew endured difficult conditions due to constant rolling of the circular hull in the high sea state. Simon Bolivar continued a high speed surface run until the evacuation point was reached enabling a transfer of the seriously ill crewman. The Simon Bolivar then returned to open ocean and resumed alert patrol status ending with a return to the Charleston SSBN site. The evacuated crew member survived though he never returned to the Simon Bolivar.

As part of a "warm – cold water" refit exchange program, in 1977 the ship conducted one "cold water" refit from the Holy Loch SSBN site in Scotland with maintenance and supply services provided by submarine tender USS Holland (AS-32). Departing Holy Loch for her assigned operating areas the ship then completed its 34th deterrent patrol. Following a trans-Atlantic transit, Simon Bolivar returned to the "warm water" Charleston SSBN site to continue its normal refit-patrol operating cycle from the continental US.

In February 1979, following her 40th deterrent patrol, Simon Bolivar entered Portsmouth Naval Shipyard at Kittery, Maine, for overhaul and conversion of her ballistic missile system to support Trident C-4 ballistic missiles. Upon completion of overhaul she returned to her home port of Charleston in January 1981.

Simon Bolivar continued to make deterrent patrols, undergoing occasional refits at Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay Georgia, and was awarded her 4th and 5th Battle "E"'s in 1982 and 1990. She successfully launched a Trident test missile in the summer of 1983.

In 1994 Simon Bolivar returned from its 73rd and final strategic nuclear deterrent patrol, 28 years after it departed port for its 1st patrol.

Master Chief Hospital Corpsman (HMCM (SS)) William R. Charette served as an Independent Duty Corpsman onboard Simon Bolivar. He was a recipient of the U.S. military's highest decoration for valor, the Medal of Honor. Known as "Doc" to his shipmates, he was held in the highest regard during his tour of duty aboard Simon Bolivar.

Deactivation, decommissioning, and disposal

Deactivated while still in commission in September 1994, Simon Bolivar under the command of Commander Forrest Novacek was both decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 8 February 1995. She was one of the last SSBN's of the original 41 for Freedom. The ship completed 73 deterrent patrols, equivalent to thirteen years of submerged strategic operations.

Her scrapping via the U.S. Navy's Nuclear-Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program at Bremerton, Washington was completed on 1 December 1995.

Life on board USS Simon Bolivar SSBN 641 1

Simon Bolivar like all U.S. ballistic missile submarines, had two crews, the Blue and Gold, in order to maximize the at-sea time of the ship itself. During the approximately 2 1/2 months of a patrol, crew members worked every day standing watches then performing their in-rate duties. Those that were not qualified in submarines had the additional requirement to complete the ship's qualification program covering all systems and machinery on board, with each section of the "qual card" requiring testing by a system expert.

Watches were 6 hours in length with three crew members rotating each watch. After watch standing, maintenance requirements and ship operations, crew members had 6–8 hours each day for sleeping and eating. Key watch stations were:

- Torpedo room, sonar, radio

- Control room (Officer of the Deck: ship control)

- Navigation center, missile control center, missile compartment, auxiliary machinery rooms

- Maneuvering room (Engineering Officer of the Watch: propulsion, electrical, reactor controls), engine room.

All were continuously manned when the ship was underway.

Each crew completed a strategic patrol cycle and then turned the ship over to the other crew. The normal patrol cycle consisted of 3 1/2 weeks of maintenance and re-supply at the SSBN refit site followed by an 11-week submerged patrol in open ocean.

The refit between patrols was a period of high intensity in order for the ship to meet its scheduled deployment date. In close concert with the supporting submarine tender, a myriad of work orders and replenishment actions were accomplished.

Hundreds of repairs and alterations were scheduled for completion. Included were ship and ordnance alterations (Shipalt, Ordalts) that removed equipment and brought upgraded replacements aboard. The ship submitted over a thousand supply requisitions to top off its onboard repair parts. Included were a wide range of spares for hull, mechanical, electrical, electronics, reactor plant and ordnance systems.

Onboard food provisions had to be brought up to a 90-day load level for a capability to serve 38,000 meals without resupply. All material and provisions were hand loaded aboard through 30" diameter hatches. Once aboard all repair parts, consumables and provisions were stored in lockers dispersed throughout the ship.

When the ship departed the refit site for its next patrol, an extraordinary range of repair and resupply had been completed. The up tempo activities with the noise and congestion from work crews, off line machinery and opened electronic cabinets was dramatically changed when the ship completed its first and only dive of the patrol. With the setting of the first watch of the patrol, "Rig for Patrol Quiet" was set and ship's routine was now starkly different from that during refit. Crew members now dressed in special lint free, easily laundered submarine coveralls for the duration of the patrol.

During patrols, operations were focused on three main objectives:

- Remain undetected,

- Maintain continuous incoming communications,

- Capability to launch missiles within fifteen minutes.

Ship's crew were constantly trained to meet these objectives under a wartime environment. Under certain tactical situations, "Rig for Ultra Quiet" was set, greatly limiting mechanical line-ups, crew activities and as a result, detectable sound emissions.

Throughout the patrol period, mission readiness was tested by emergency action messages being sent to the ship. Many of these "EAM's" would result in full crew participation with sounding of the General Alarm followed by "Man Battle Stations, Missile. Spin up All Missiles". The Officer of the Deck would immediately direct Sonar to conduct a full sweep for all contacts, and initiate actions to bring the ship to required depth, buoyancy and speed to commence the Hover procedure required for missile launch. Once all battle stations were manned, the crew waited for the announcement " Set Condition 1SQ, This is the Captain, this is an Exercise".

Ship's sonar operators continually searched for contacts, all of which were classified for possible threat to the ship's mission. Should a contact be classified as a Soviet warship, the General Alarm would be sounded for "Man Battle Stations, Torpedo". The full suite of the torpedo fire control system would be manned and readied for weapons launch until intent of the threat was determined.

A continual series of damage control drills were conducted during patrols to mitigate ship casualties due to:

- Flooding, fire, collision,

- Missile emergency, radiation, toxic gas,

- Loss of ship control, reactor shutdown ("scram").

- Alarms on submarines of the United States Navy.

If the simulated casualty involved contamination of the ship's atmosphere, all crew members donned Emergency Air Breather EAB masks to access special air flasks isolated from the ship's atmosphere.

A reactor scram would initiate a complex series of engineering and ship control procedures. When the Engineering Officer of the Watch reported "Reactor Scram" to the Officer of the Deck in the Control Room, the effects on the ship were due to the loss of high pressure steam to the Main Engines for propulsion and to the Turbine Generators for electrical service.

The Rig for Reduced Electrical bill was immediately implemented as electrical service was switched to the submarine's battery. All non-vital loads were dropped from the electrical busses. Limited propulsion was available from the emergency electrical motor operating the main shaft. All vital machinery and propulsion were now powered by the limited capacity ship's battery.

To ensure the viability of the ship and its mission, additional electrical power to supplement the battery was required until the reactor could be returned to service for steam generation. The ship's emergency diesel needed to be brought into service. This required the submarine to proceed to periscope depth in order to raise the snorkel mast for induction and exhaust for the ship's diesel.

The Officer of the Deck would appraise the tactical situation before commencing preparations for proceeding to periscope depth. "Prepare to snorkel" would be ordered over the 1 MC, the ship-wide announcing system. The ship would first be brought to periscope depth followed by a shallower snorkel depth. When preparations to snorkel had been completed, the order was issued to "Commence snorkeling".

Back-up electrical capacity was now available. While recovery from the reactor scram continued, the ship remained at snorkel depth with multiple masts raised; periscope, snorkel mast, ESM mast, communications mast, and at times the satellite navigation mast. At higher sea states, the shallow depth required diligent ship and depth control to prevent the broaching of the hull, and the loss, by cutting from the screw, of the VLF floating wire streaming from the sail.

With recovery of reactor power, the ship would secure "rig for reduced electrical" and snorkeling, lower all masts and antenna, and return to patrol depth.

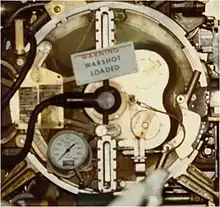

For self-defense, warshot Mark 48 torpedoes designed to sink deep-diving nuclear-powered submarines and high-performance surface ships were always loaded in two of the four torpedo tubes. Proficiency in target tracking and fire control solution – target course, speed and range – was periodically tested at the Navy's AUTEC instrumented underwater firing range at Andros Island in the Bahamas. Exercise versions of the Mk 48 torpedo were fired at targets that simulated aggressor submarines and surface warships.

Prior to fitting out with the MK 48 torpedo in the 1970s, the ship's weapons load included at various times the Mark 14 torpedo, Mark 37 torpedo and Mark 45 torpedo.

At the end of the alert period of the patrol, target packages assigned to the ship were assumed by another SSBN that had gone to alert status. The VLF floating wire for continual incoming communications was reeled-in, and ship proceeded towards its refit site at greater speed and depth.

Approaching the continental shelf, the ship moved from deep ocean to much shallower waters. In preparation for its first surfacing, the requisite sonar searches and contact confirmations would be made. The officer of the deck would be temporarily relieved by a second OOD, enabling the watch OOD to be prepared to re-establish his watch in the ship's sail after surfacing had occurred. The quartermasters would break out the portable communications console ("bridge suitcase") that would enable the OOD in the sail to have communications with the control room.

When all preparations had been completed, the captain would order the OOD to surface the ship. "Surface, Surface, Surface" would be announced on the 1MC. Two methods could be used for the surfacing. Either the main ballast tanks would be blown of water by high pressure air, or the ship would be broached, the snorkel mast raised as part of the Ventilation Bill, and the low pressure blower would be started with discharge to the main ballast tanks.

With ship now surfaced, the Lower Hatch in the control room would be opened. The OOD and a look-out would scramble up the ladder inside the sail to the Upper Hatch. With this second hatch opened watertight integrity ended and quick access to underside of the sail would be made. Unpinning the locking mechanism for the "clam shell" allowed the fairing on top of the sail to be lowered.

The watchstanders would now be in the open air of the cockpit atop the sail, and control could be transferred back to the original OOD once the bridge suitcase had been installed and tested. The ship would then proceed as a surface vessel to the inbound channel for passage to the SSBN refit site, and the beginning of the next patrol cycle.

During the off-crew period, critical skills were practiced and enhanced at the Fleet Ballistic Missile Training Center at the naval base where off-crews were located (Naval Base Charleston for Simon Bolivar). Specialized facilities were used for sonar, weapons and engineering training. Included was a control room simulator in which control room watchstanders (Officer of the Deck, Diving Officer, Chief of the Watch and planesmen) could practice realistic casualty responses that could not be simulated on board the submarine.

One critical control room scenario was breaching of the ship's submerged operating envelope due to deep depth, high speed and stern plane malfunction. The ship would immediately take a severe down angle in excess of 45 degrees, and rapidly pass through test depth. The OOD would immediately order "Emergency Blow the Forward Main Ballast Tanks" together with "All Back Full". Close monitoring of inclinometers and accelerometers followed to determine reversal of the ship's descent towards crush depth. Next, precise timing for Emergency blowings and venting selective ballast tanks was required together with rapid changes in forward and reverse propulsion. Stabilization of buoyancy with minimal speed was needed at shallower depth to hover for repair to the control surfaces.

At the other end of the operating envelope were procedures for coming to periscope depth. Once the ship completed contact evaluation, a relatively shallow depth was ordered. At this depth, the periscope was raised but remained underwater with visual sweeps being made.

The Diving Officer was then ordered to proceed to periscope depth. Should the OOD detect a hull shape as the ship ascended, the code words "Emergency Deep" would be shouted out. Without further orders, the diving party would sound the Collision Alarm, move fairwater and stern planes to full dive, ring up All Ahead Full, and flood 10,000 pounds of water into depth control tanks, all designed to reverse the ship's upward momentum towards a potential underwater collision.

The control room watchstanders could, through repeated trials in the simulator, master the necessary timing and actions to ensure recovery from these type of casualties, in addition to a range of others.

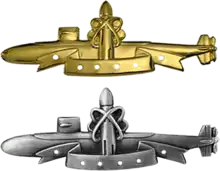

The Submarine Warfare Insignia ("Dolphins") was worn by Bolivar crew members who successfully completed Qualification in Submarines, a rigorous program for naval personnel assigned to a submarine. Once an enlisted sailor has earned the right to wear the Silver "Dolphins", (SS) was added after his rate denoting "submarine specialist". A crewman who completed a strategic deterrent patrol was authorized to wear the SSBN Deterrent Patrol insignia. After completion of twenty successful patrols, the SSBN pin is upgraded to a gold design.

References

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641). |

- 1 Attribution to crewmember of USS SIMON BOLIVAR (SSBN 641) GOLD

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- This article includes information collected from the Naval Vessel Register, which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain. The entry can be found here.

- Photo gallery of USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641) at NavSource Naval History

- hazegray.org: USS Simon Bolivar (text), retrieved 25 September 2011